The world has a lot to thank Bangladesh for! Oral Rehydration Therapy, a simple combination of salt and sugar, has saved more than 70 million lives in the 45 years since ICDDR,B in Bangladesh first developed it. The Lancet called ORS “the most important medical advance of the 20th century”.

Bangladesh is also credited with the invention of joint liability group-based lending – the foundation for microcredit across the globe. 50 years into the independence of Bangladesh, we take a look at the contributions of its four most influential microfinance institutions:

- Grameen Bank originated a structured and formal approach to microfinance. As a result, it influenced generations of microfinance institutions (MFIs) at home, and built capacity abroad through Grameen Trust.

- BRAC developed a multiservice model of social development and enterprises in Bangladesh. It exported its expertise in microfinance across numerous geographies in Africa and Asia.

- ASA innovated a model for sustainable scaling up of a microfinance network through standardized self-reliant branches.

- BURO Bangladesh unlocked a holistic approach toward microfinance by integrating open savings mechanisms, pivoting away from the industry’s exclusive emphasis on lending.

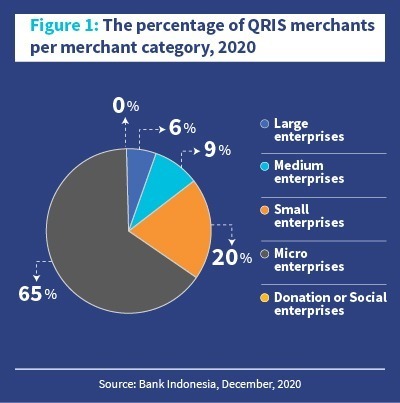

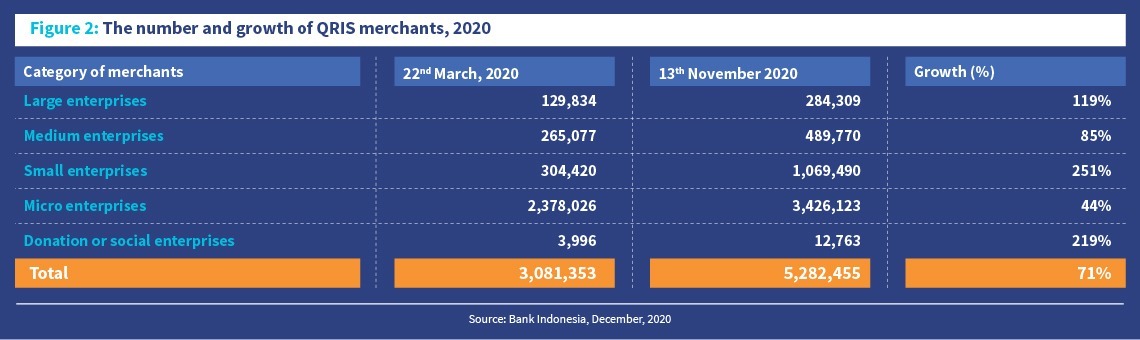

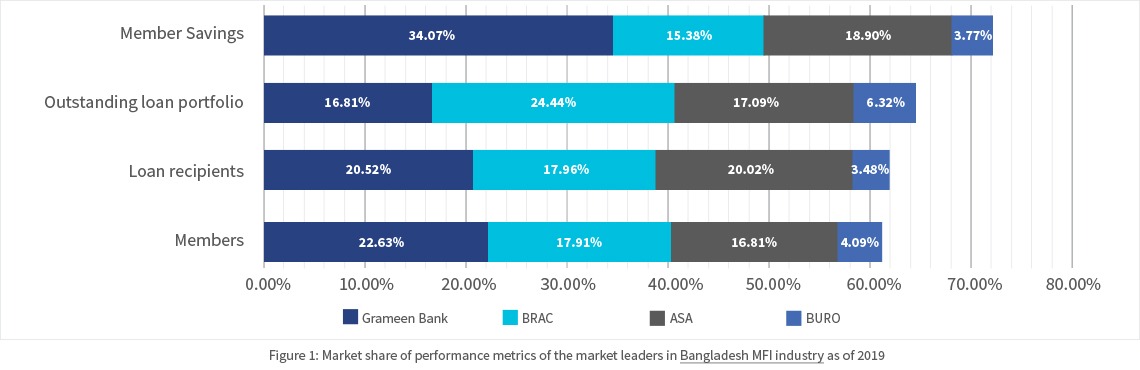

These four entities collectively have >60% of the market share among the 495 MFIs that Credit & Development Forum (CDF) reports on.

1. Grameen Bank: the origin of microfinance

The genesis of formalized microfinance in Bangladesh began during the Bangladesh famine of 1974. Muhammad Yunus, then a professor at the University of Chittagong visited Jobra. There, he learned that the basket weavers relied on exploitative money lenders to buy their raw materials. Yunus decided to make a small loan of USD 27 (equivalent to BDT 856 at the time) out of his pocket to a group of 42 families so they can produce items and sell them for profit. Seeing the positive impact this had, Yunus developed the guidelines for Grameen Bank. The Grameen Bank project started in Jobra in 1976 and was extended in 1979 to Tangail district with support from the Bangladesh Bank. In 1983, the Grameen Bank project was established as an independent bank under the Grameen Bank Ordinance 1983.

The Grameen approach broke barriers of availing credit for the poor by pioneering the joint-liability lending model, offering collateral-free loans. Grameen mainly served women as it found that they generally repay loans on time, invest their money for productive purposes, and make expenditures to improve the quality of life of family members. Grameen also believed that this increased women’s agency over resources by enhancing their traditional role as household budget managers.

After the 1998 floods, Grameen Bank faced high levels of delinquency and reinvented itself as “Grameen II”, which offered both savings services and (nominally at least) more flexible repayment options. Within three years, Grameen’s deposit base tripled and its loans outstanding doubled.

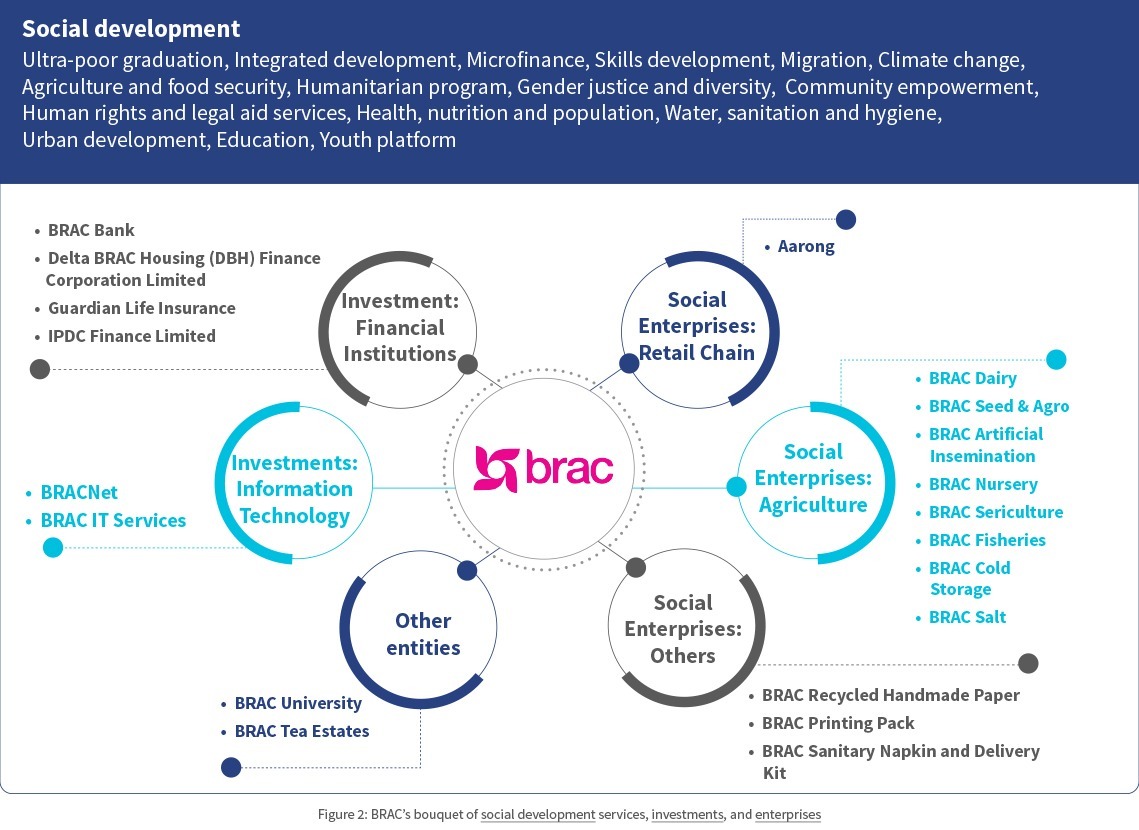

2. BRAC: a multi-faceted approach to social development

Sir Fazle Hasan Abed initiated BRAC as a project in 1972 at Sulla, a sub-district of Sunamganj, in Bangladesh. This small-scale relief and rehabilitation project helped returning refugees after the Liberation War by building homes and fishing boats. In the late 1970s, BRAC focused on combating diarrhea, through the Oral Therapy Extension Program (OTEP). It trained mothers to prepare and administer oral rehydration solution (ORS) from molasses and salt – ingredients available in every Bangladeshi home.

In 1986, BRAC started its Rural Development Program (RDP) consisting of four pillars:

- Institution building

- Functional education and training

- Microcredit

- Income and employment generation

From there, BRAC rapidly evolved into the world’s largest, most feted and diverse not for profit organization, offering holist development solutions to millions of poor people across the globe. Microcredit was but one strand of BRAC’s multi-faceted interventions to address poverty.

3. ASA: a frugal alternative for sustainable microfinance

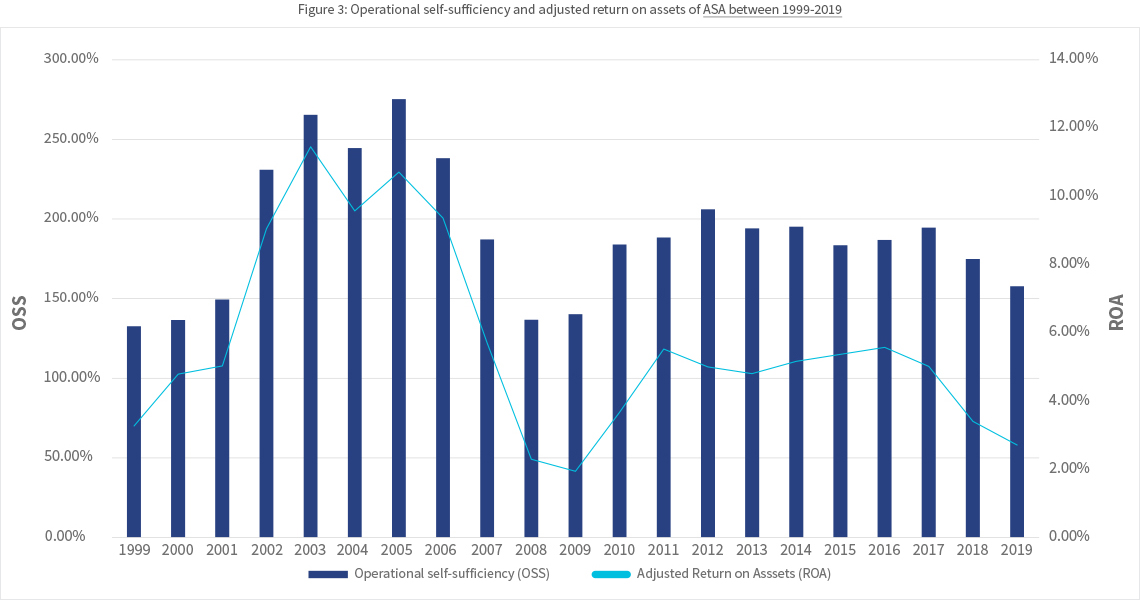

Md. Shafiqul Haque Choudhury established ASA in 1978 to empower rural landless villagers from the bottom up through people’s organizations. Initially, ASA attempted to combine social development with credit provision, similar to BRAC’s approach. However, in 1991, ASA pivoted to a sole focus on microcredit lending. The objective of this shift was to overcome a dependence on international donor agencies and become a specialized microfinance organization that was financially self-sufficient. ASA soon became the most profitable MFI in Bangladesh, generating annual net surpluses since 1992. As a result, ASA consistently recorded some of the highest return on assets and operational self-sufficiency among MFIs. As of 2019, ASA has a return on assets of 5.9% and a return on equity of 11.11%.

ASA’s self-reliant model is based on standardization of operations and streamlining of services. An easily replicable and low-cost branch model, and decentralized approach allowed ASA to make quick decisions. ASA was able to reinvest surpluses from the individual branch operations to multiply their branches, turning the organization into a fully self-sufficient entity independent of donors and commercial creditors alike. ASA focused on growing its standard product instead of product diversification, which resulted in ASA capturing a large share of the untapped market through its efficient delivery mechanism.

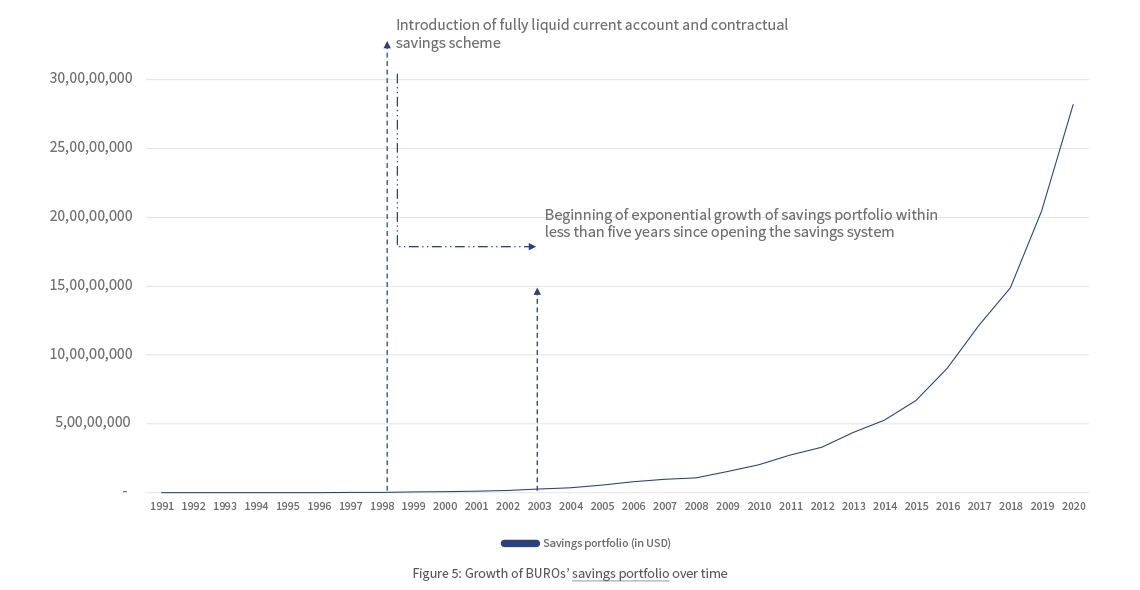

4. BURO Bangladesh: bridging the gap between microcredit and microfinance

Since its inception in 1990, BURO identified and responded to poor people’s need for savings services. Grameen Bank and BRAC offered only locked-in “compulsory” savings. This meant that customers could not withdraw their savings at will, and were only able to access them when permanently leaving the organization. BURO introduced partial savings withdrawal in 1990, and moved to completely open access saving system unaffected by loan outstanding in 1998. This led to a substantial increase in deposits and net savings. BURO’s approach led to protests and mass default by Grameen Bank’s clients in the mid 1990s, demanding access to their locked-in savings.

Based on the experience gained during its formative years, BURO acknowledged that microcredit in a vacuum is not effective in significant poverty alleviation, let alone poverty eradication. BURO revolutionized the microcredit landscape of Bangladesh by overcoming the industry’s obsession with credit alone and integrating savings into the range of offerings for the clients. BURO continues to lead much of the innovation and broadening of the range of financial services offered by MFIs in the country.

5. How did these four perform?

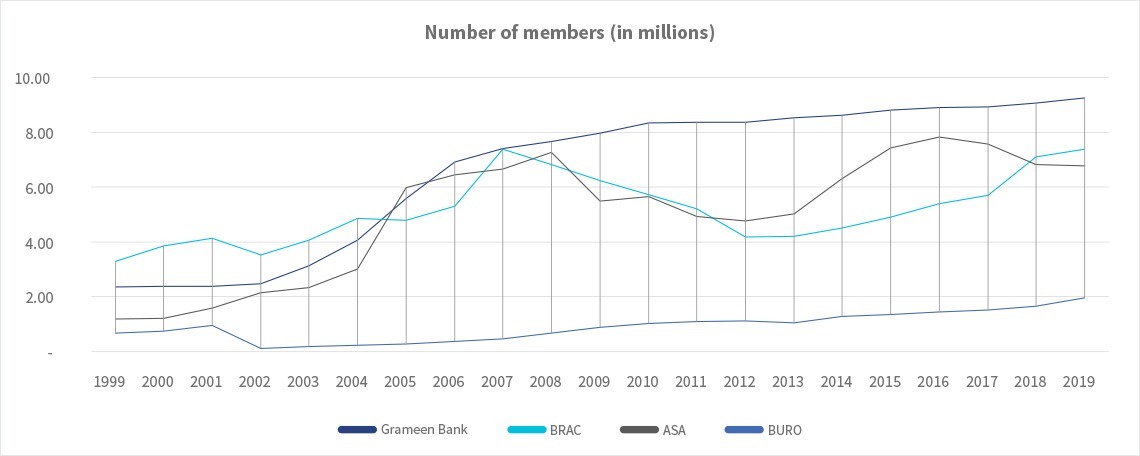

The graph below highlights the ebb and flow of membership amongst the “big four” as they grew and adjusted overtime. Grameen Bank’s rapid growth in membership starting in 2002 reflects the introduction of the popular Grameen II model. The reduction in membership by BRAC and ASA from 2007 highlights their concerns about multiple membership and over indebtedness, which was beautifully highlighted by Chen and Rutherford in 2013. There is little question that multiple membership of MFIs continues today – indeed it offers a way for borrowers to navigate the largely inflexible annual loan with weekly repayments offered by them all.

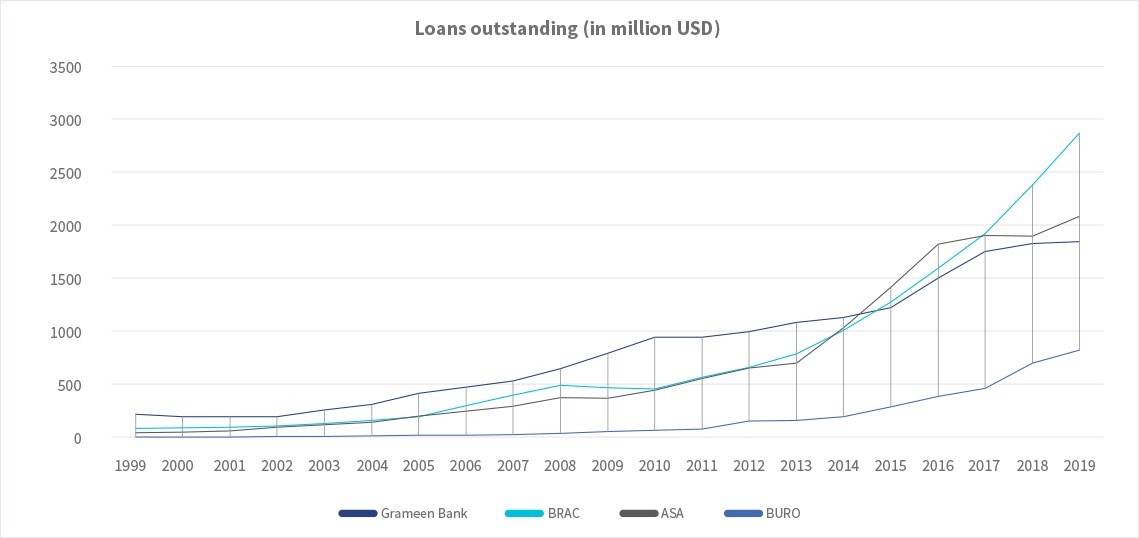

Loans outstanding have grown similarly, but the scope and scale of BRAC and ASA’s larger individual lending programs means that their average loan size per member is significantly higher than that of Grameen Bank.

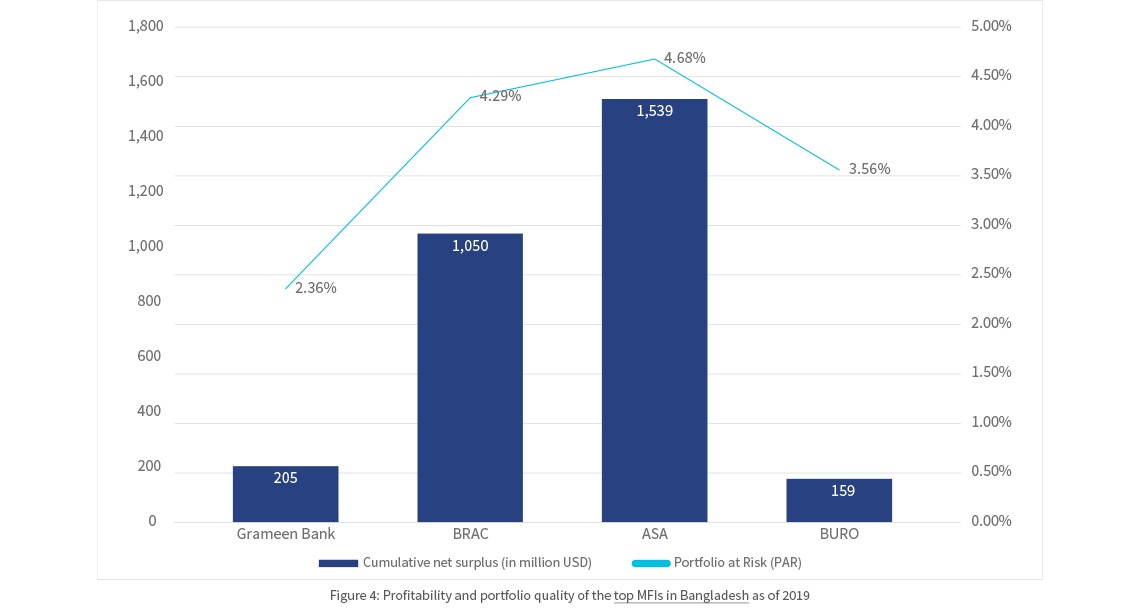

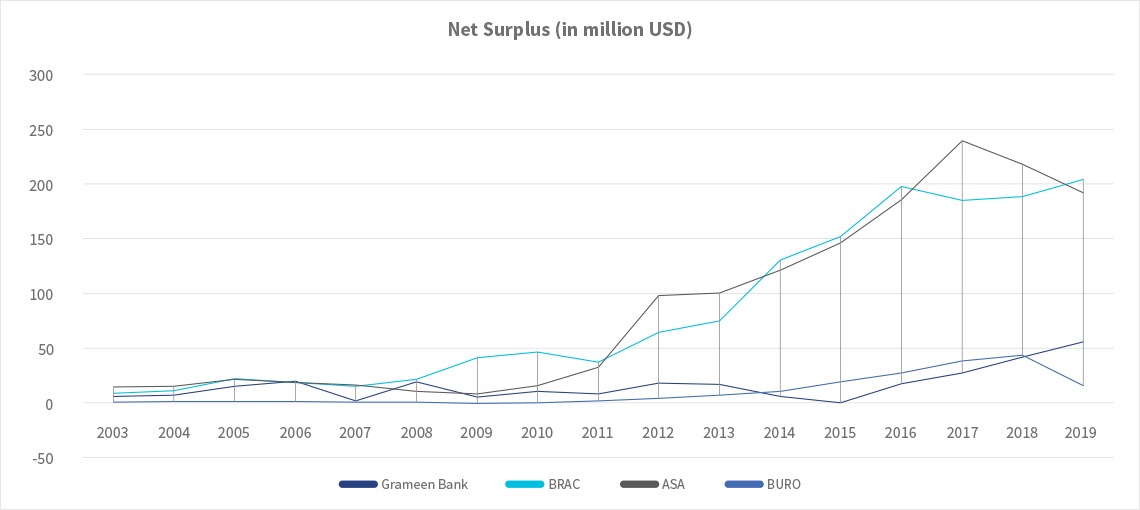

The profitability of these organizations also varies significantly. ASA, through is simplified model, and BRAC through cross subsidies from its other programs, generating much larger surpluses each year.

6. Influence and global expansion of microfinance models of Bangladesh

The biggest impact that came as a result of Grameen Bank’s early success was convincing the banks and other people that the poor are bankable, they utilize their loan and repay on time, performing better in contrast to the wealthy borrowers of the bank. The simple effectiveness of the model conceived by Grameen Bank has inspired many NGOs to emulate the model and offer similar financial services to the poor. Professor Yunus created Grameen Trust in 1989 as a private, not-for-profit NGO to cater to the demands of people and organizations that wanted to learn how to replicate the success of Grameen Bank. Since its inception, Grameen Trust has provided assistance to 151 organizations in 41 countries.

BRAC rapidly expanded its operations across geographies in Africa and Asia in the 21st century. BRAC established Stichting BRAC International in 2009 as a non-profit foundation headquartered in the Netherlands to manage all BRAC entities outside Bangladesh. BRAC commenced operations in Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Uganda, Tanzania, Pakistan, South Sudan, Sierra Leone, Liberia, the Philippines, Myanmar, Nepal, and Rwanda in a span of less than two decades from 2002 to 2018. By 2020, BRAC had already been ranked the #1 NGO in the world for the fifth consecutive time by NGO Advisor, an independent Geneva-based media organization. BRAC ranked as the top NGO for the first time in the Global Journal’s list of the 100 Best NGOs in the world in 2013.

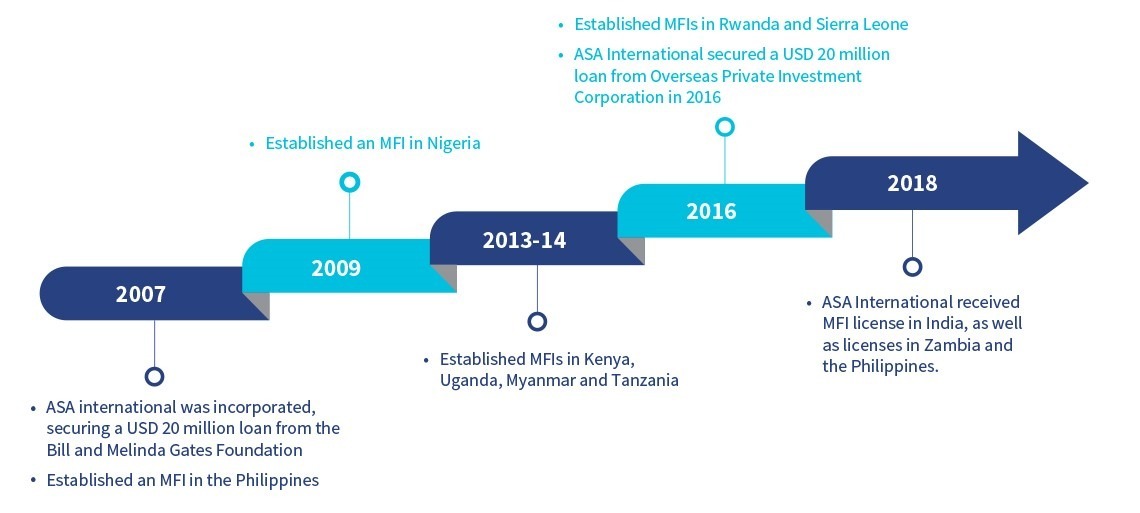

ASA has also expanded its operations beyond Bangladesh, as international roll-out of the ASA model has resulted in sustainable growth and returns.

ASA International currently has 1,961 branches, over 2.4 million clients, and an outstanding loan portfolio of USD 418.5 million in thirteen countries outside Bangladesh.

Fifty years on Bangladesh has exported a remarkable diversity of products from garments to ORS, but one of its key legacies is microfinance – in many forms.