As the COVID-19 pandemic started to exact a toll on lives and livelihoods in early 2020, countries imposed strict lockdowns to stem the spread of infections, disrupting economies and societies across the world. With pandemic-induced constraints on in-person interactions, many countries adopted a “digital first” approach to delivering social assistance, primarily cash transfers. How did these digital systems perform? What worked and what did not? And, as the world still grapples with COVID disruptions, including periodic lockdowns, how can governments better design and implement social assistance in an increasingly digital environment?

In a new CGD policy paper, we look at India’s experience to begin answering these questions. Together with a strict lockdown and information campaign, India’s early response to the COVID-19 pandemic included the launch of the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY), a major social protection package covering both in-kind food distribution and cash transfers to women, the elderly, and farmers. We draw lessons from a nationally representative household survey conducted in India during April and May 2020, shortly after the launch of the program, and find that while PMGKY was by many measures successful in delivering benefits, there remains room for improvement.

How India implemented PMGKY

Unlike countries such as Colombia, Brazil, and Pakistan, India did not immediately launch a major new program targeted towards the “new poor”—the mostly informal-sector workers and urban wage laborers who lost their livelihoods and left cities for rural areas in the aftermath of the lockdowns. Instead, PMGKY built on five of India’s many existing social programs and one new program targeted at women to deliver additional benefits. For nearly a decade prior to the pandemic, India had invested in building digital platforms to transfer social benefits directly to beneficiary bank accounts, as well as to help manage the public distribution system for food rations. By early 2020, the vast majority of households were included in the “JAM”—the combination of digital ID (Aadhaar), Jan Dhan bank accounts, and mobile phones—making it possible for the government to implement a “digital first” social assistance strategy.

What did we find?

First, a caveat. The early stages of the lockdown were extraordinary times, with severe disruptions to the “real” economy—local and country-wide transport, commerce, and the functioning of supply chains. School closures suspended India’s school feeding program—the largest in the world—affecting nearly 144 million children and imposing an additional burden on poor households, especially women. These disruptions made transactions of any sort difficult, including those conducted digitally within aid programs, as physical goods must eventually be delivered to those in need. There is, therefore, a limit on what can be expected from even well-functioning digital systems, starting from the point at which they interface with real activity.

That said, in general, the survey results point to a relatively successful rollout of social assistance at scale: India’s relief measures reached nearly a billion people in a short time, with many households benefiting from multiple programs. Digital systems were instrumental in sustaining and rapidly scaling up financial assistance, no doubt helped by the decision to route benefits through existing programs rather than create new ones. However, many registered beneficiaries faced challenges in realizing the assistance, partly because they were not fully aware that it had been provided to them, and also because of perceived and real difficulties at points-of-service.

The in-kind public distribution system also played a vital cushioning role, possibly with the highest percentage of recipients receiving and realizing their benefits.

Based on survey responses, many people reported not receiving their full benefit in addition to the extra PMGKY food allowance, but it is not clear whether everyone who received the additional ration actually understood that it had been distributed to them because it was free.

Our analysis suggests that the delivery systems were not biased against any particular set of beneficiaries.

The patterns of responses do show statistically significant differences in the experience of different groups (urban/rural, male/female, etc.) but these are not large enough to undermine the general picture. Gender effects were limited, place of residence had only a modest effect on survey response with no consistent pattern, and there is no evidence that poor households had less success in accessing benefits.

Smartphones provided key benefits for communications, including awareness of social assistance as well as information on COVID-19.

Smartphone owners were more likely to be aware of at least one coronavirus symptom and more likely to report receiving information about the virus through six of the seven media channels polled, especially social media and YouTube. Smartphone owners were also more likely to receive information on the PMGKY package, with less need to check bank balances manually on passbooks or through local officials.

Among our respondents, 74 percent reported that at least one person within their household possessed a smartphone, indicating deep penetration both in rural and urban India.

Moreover, the survey provides no indication that smartphone ownership is dependent upon income; although men and urban dwellers were statistically more likely to report owning one. In short, a smartphone is no longer a luxury in India.

Despite unprecedented pressure to deliver benefits, the payments systems themselves appear to have worked reasonably well.

However, it was not always easy for people to get the benefits. The first impediment to realizing the financial transfers was that beneficiaries were not consistently aware that these had been paid into their accounts. In many cases, beneficiaries needed to verify bank balances manually, a process that was often complicated by lockdown conditions. The second related to the logistics of safely accessing cash-out facilities while complying with COVID prevention measures, a common problem across many countries that delivered social assistance digitally.

India offers lessons on the interaction of “real” and “digital” relief programs during an unprecedented emergency. Digital mechanisms have played a vital role. But even in a country that has made huge investments in digital ID and payments infrastructure, our research highlights the importance of local institutions and human resources to reach large numbers of people.

The Center for Global Development first published this blog on 22nd July, 2021.

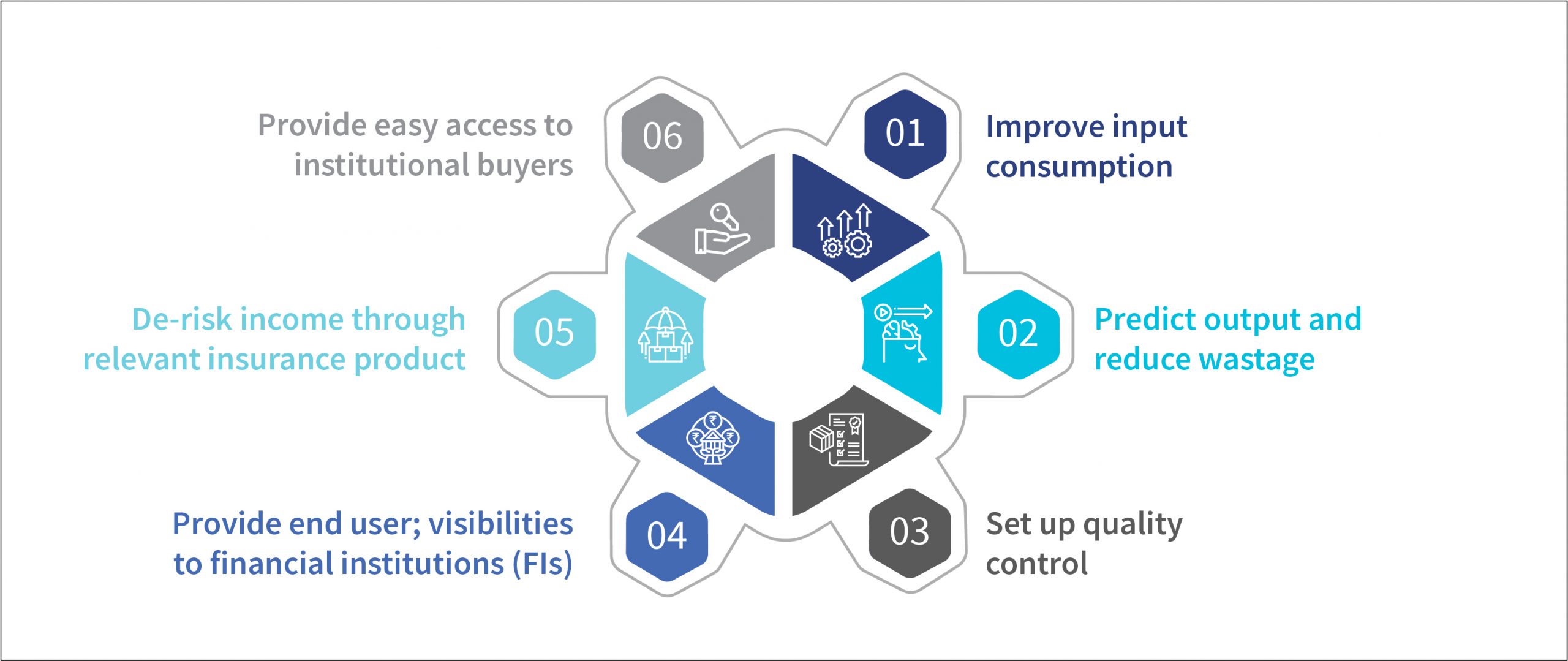

After multiple iterations and tweaks to their product offerings, the team identified access to reliable markets with a predictable price for their produce as the major need of farmers. They also analyzed the demand side, mainly institutional buyers who purchase from FPOs in bulk, such as intermediaries for retailers who supply to

After multiple iterations and tweaks to their product offerings, the team identified access to reliable markets with a predictable price for their produce as the major need of farmers. They also analyzed the demand side, mainly institutional buyers who purchase from FPOs in bulk, such as intermediaries for retailers who supply to

She harvested her

She harvested her

Founded by Prathmesh Kant and Akhil Sharma in 2017,

Founded by Prathmesh Kant and Akhil Sharma in 2017,

Whrrl works on a disruptive model unique to the current scenario. It collects data from warehouses and feeds it to its blockchain system, which creates an immutable record of the collateral

Whrrl works on a disruptive model unique to the current scenario. It collects data from warehouses and feeds it to its blockchain system, which creates an immutable record of the collateral