“The biggest impact of COVID-19 on my livelihood is the closure of my primary business. The inter-county travel restrictions and curfews had hurt customer footfall and I was left with no choice but to shut my shop.” Philip, a furniture enterprise owner from Nairobi.

Social and economic disruptions brought about by COVID-19 are projected to contract Kenya’s economy between 1% and 1.5%. As per a World Bank report, since the pandemic struck, two million more people in the country have fallen below the poverty line and around one-third of household-run businesses have not been operating. The Central Bank of Kenya warned that 75% of businesses risk closure due to the lack of emergency funds and crisis in liquidity. Further, a study by BFA on COVID-19 indicates that more than 80% of Kenyan respondents reported a decline in income while 67% reported an increase in expenses. Along with the loss of livelihoods, remittances have fallen while few households have benefitted from direct cash assistance.

In this blog, we present key insights from MSC’s research[1] into the impact of the pandemic on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). We conclude with recommendations for the government to formulate policy measures to support the recovery of Kenyan MSMEs and build their resilience.

Entrepreneurs face declining business revenues and increasing expenses, which have jeopardized the survival of micro and small enterprises

MSMEs play a vital role in the economic development of Kenya. The sector largely comprises micro-enterprises (98.3%)[2] and contributes approximately 40% to the GDP[3]. MSMEs employ 14.9 million people, of whom 12.1 million are employed in microenterprises. However, the sector remains highly informal as only 20% of the 7.4 million MSMEs operate as licensed entities.

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the general economy. Many enterprises have closed and people have lost their jobs. As a result, the purchasing power of consumers is constrained. Consumers spent less on discretionary expenses and limited their consumption to focus on essential goods. While the economy is gradually reopening and the restrictions have been relaxed, the consumers are diffident and have been spending cautiously.

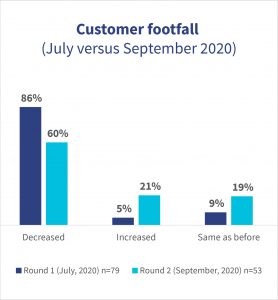

In our two dipstick surveys, we found that most entrepreneurs have struggled with falling business revenues as a result of reduced customer footfall and decreased volume of sales per customer. Furthermore, business expenses increased as travel restrictions hurt supplies and increased prices. Some entrepreneurs who borrowed from financial institutions have found it difficult to repay their loans.

In our two dipstick surveys, we found that most entrepreneurs have struggled with falling business revenues as a result of reduced customer footfall and decreased volume of sales per customer. Furthermore, business expenses increased as travel restrictions hurt supplies and increased prices. Some entrepreneurs who borrowed from financial institutions have found it difficult to repay their loans.

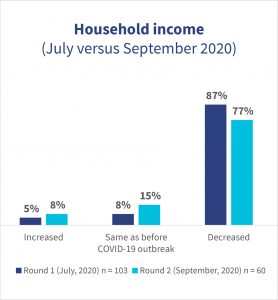

Furthermore, the household incomes of micro and small enterprise owners have generally declined, as members of the household have either lost jobs or seen a lower footfall in their enterprises. However, 32% of entrepreneurs in September, 2020 and 82% of entrepreneurs in July 2020 reported an increase in household expenses.

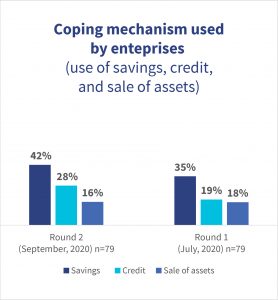

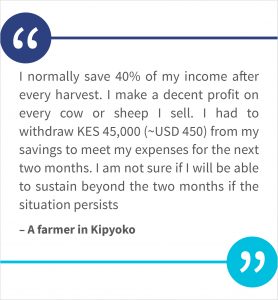

MSMEs operate with limited resources and hence are less able to absorb heightened costs that result from shocks like COVID-19. Most entrepreneurs mentioned that they have exhausted whatever little financial reserves and savings they had. The use and eventual depletion of savings

have increased as many enterprises continue to face a significant decline in income. As a result, only a few entrepreneurs have the resilience to recover after the pandemic, and unless supported, many enterprises will eventually fail to survive the crisis.

have increased as many enterprises continue to face a significant decline in income. As a result, only a few entrepreneurs have the resilience to recover after the pandemic, and unless supported, many enterprises will eventually fail to survive the crisis.

Some entrepreneurs turned to credit and sold off assets to meet household needs but these provided only temporary relief. More female than male respondents reported resorting to the sale of productive assets, especially those based in rural areas and involved in agricultural enterprises. Entrepreneurs who resorted to borrowing reported being trapped in a vicious cycle of repeat borrowing to manage repayments.

A squeeze on credit and limited access to capital has further diminished the ability of enterprises to survive the crisis

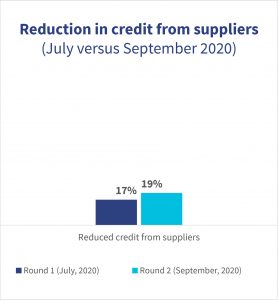

Two specific external sources of capital fueled enterprise value chains before COVID-19. These were loans from financial institutions and the provision of credit from suppliers. The reduction in access to credit from both sources has posed significant challenges for enterprises to maintain business liquidity.

Most financial institutions have reduced their exposure to the MSME segment given its higher levels of vulnerability and lower resilience. Some lenders asked for additional collateral or priced the loans higher than usual, which reflects the higher perceived risk associated with MSMEs. Such conditions have made loans expensive for MSMEs and thus have limited their ability to use additional loans to reestablish business.

Under normal circumstances, suppliers provide goods to entrepreneurs on credit for short terms, usually 15 to 45 days. Yet suppliers have reduced sales on credit. This is because liquidity is crunched in the value chain due to limited funding from financial institutions, a decrease in sales, and increased expenses. Moreover, some enterprises have defaulted on payments to suppliers, which has reduced the ability of suppliers to offer goods on credit to other entrepreneurs. Thus, most entrepreneurs are now forced to make only cash sales to preserve their liquidity and pay suppliers. Hence, they extend credit sales only to their most important customers. This measure has also reduced sales.

Under normal circumstances, suppliers provide goods to entrepreneurs on credit for short terms, usually 15 to 45 days. Yet suppliers have reduced sales on credit. This is because liquidity is crunched in the value chain due to limited funding from financial institutions, a decrease in sales, and increased expenses. Moreover, some enterprises have defaulted on payments to suppliers, which has reduced the ability of suppliers to offer goods on credit to other entrepreneurs. Thus, most entrepreneurs are now forced to make only cash sales to preserve their liquidity and pay suppliers. Hence, they extend credit sales only to their most important customers. This measure has also reduced sales.

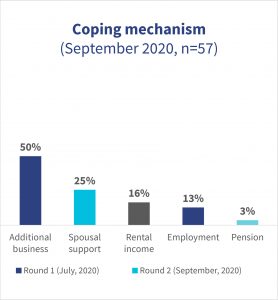

Coping mechanisms by entrepreneurs include diversification of income and businesses

Some entrepreneurs have responded to the risk of business failure by switching their existing products and services to suit the immediate demands of customers. The entrepreneurs who have two or three concurrent businesses have focused on those businesses with stronger cash flows.

Some entrepreneurs have responded to the risk of business failure by switching their existing products and services to suit the immediate demands of customers. The entrepreneurs who have two or three concurrent businesses have focused on those businesses with stronger cash flows.

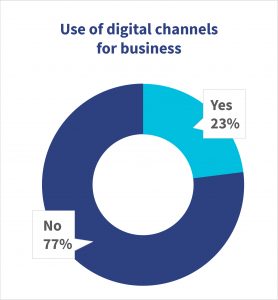

The uptake of digital platforms and technologies by enterprises, particularly micro and small enterprises, has been limited

The pandemic has led to a limited increase in the adoption of digital platforms across urban and rural areas. WhatsApp, Facebook, and other e-commerce platforms provide an opportunity to enhance sales. However, the lack of awareness and understanding to use digital platforms among entrepreneurs have limited the uptake. Among enterprises surveyed in September, 2020, 73% have reported using digital transactions, such as mobile money and electronic bank transfers up from 60% in July 2020.

The pandemic has led to a limited increase in the adoption of digital platforms across urban and rural areas. WhatsApp, Facebook, and other e-commerce platforms provide an opportunity to enhance sales. However, the lack of awareness and understanding to use digital platforms among entrepreneurs have limited the uptake. Among enterprises surveyed in September, 2020, 73% have reported using digital transactions, such as mobile money and electronic bank transfers up from 60% in July 2020.

Recent times saw digital transactions in the country rise, buoyed by the Central Bank of Kenya’s directive that waived the fee on mobile money transactions of less than KES 1,000 (~USD 10) and bank to mobile wallet transfers. While digital merchant payments witnessed a net decline of 16%[4], enterprises in sectors, such as agriculture and food and grocery experienced an upward trend in digital payments.

Measures that the public and private sector can take to support this segment to tide over the crisis

To support the entrepreneurs and enhance their income from their enterprises:

- The government may mobilize funding from multilateral agencies to provide one-time emergency relief cash support to enterprises, preferably to women-owned enterprises.

- The government may review and suitably modify procurement guidelines to encourage and support local enterprises, especially women-owned enterprises.

- The government can establish a multi-agency platform and collaborate with the private sector to support enterprises with access to digital technologies, and use e-commerce and social commerce, digital payments, and alternate modes of financing—including those from the private sector.

To support the entrepreneurs and reduce the burden of expenses of their enterprises:

- The government may formulate forward-looking policies that combine incentives and tax-reliefs to revive the sectors affected most by the restrictions. Such policies will reduce the overall operating costs and provide the much-needed revenue and liquidity for enterprises.

- Donor agencies may support the financial industry by promoting concessionary financing modalities, such as guarantee funds for specific enterprise sectors that have been affected by the pandemic. These will enable and encourage financial institutions to provide loans with generous terms and conditions to help enterprises continue their business.

To support the entrepreneurs and boost access to finance for their enterprises:

- Donor agencies may fund technical support to financial service providers, including fintechs, to develop innovative products for enterprise finance, such as business interruption solutions, as well as bundled savings, credit, and insurance products.

- The government and the central bank may run an awareness campaign to encourage enterprises to seek refinancing and restructuring options from their lenders so that in case of non-repayment, the suspension of listing the negative information[5] of borrowers would not affect the entrepreneurs’ credit scores.

To benefit enterprises in the informal sector:

- The Micro and Small Enterprise Authority as the nodal agency can consider providing support to enterprises for business continuity and recovery by preparing them to adapt the delivery of products and services in line with the prevailing business environment and changing customer demands. The government may allocate a budget to extend this support.

- The government should increase the formalization of informal enterprises by encouraging them to register and by supporting them to comply with regulatory requirements.

- Donor agencies may assist financial service providers to offer advisory support to help enterprises develop mid- and long-term risk mitigation strategies. This in turn can help financial institutions earn customer loyalty and improve the quality of their loan portfolio by stemming rising defaults.

Enterprises have faced severe disruptions in demand and payment cycles, considering their limited net worth, low backup of savings, and a squeeze on their access to finance. The micro and small enterprises sector needs appropriate responses at all levels to support its recovery in the aftermath of the crisis.

[1] The sample size of the research is, clearly, too small to be representative and therefore the percentages reported throughout should be seen solely as indicative.

[2] KNBS MSME survey 2016

[3] KAM-Focus on SMEs-

[4] FSD Kenya: How COVID-19 has affected digital payments to merchants in Kenya

[5] In April, 2020, the CBK suspended listing of negative information of borrowers on the Credit Reference Bureau by commercial banks. This was to cushion borrowers who were unable to repay their loans due to the effects of the pandemic, such as job loss or disruption in business. The CBK however, lifted the suspension in October, 2020 due to rising loan defaults that affected the financial sector.

Subsequent relaxations of restrictions have improved sales, but demand remains low. The cost of transportation also remains high along with the high cost to procure raw materials. A study by the research firm

Subsequent relaxations of restrictions have improved sales, but demand remains low. The cost of transportation also remains high along with the high cost to procure raw materials. A study by the research firm

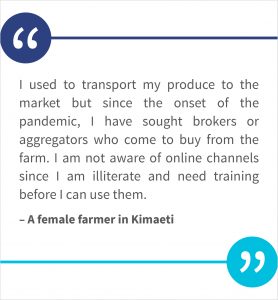

Digital technologies could provide solutions to some of the issues that face farmers, especially those related to access to markets and credit. However, the uptake of these technologies and platforms is limited among farmers. Only 40% of those surveyed have a smartphone and only 13% used digital agriculture extension services. Lack of awareness and sound digital literacy, financial constraints, and limited digital capability are key factors that led to low uptake.

Digital technologies could provide solutions to some of the issues that face farmers, especially those related to access to markets and credit. However, the uptake of these technologies and platforms is limited among farmers. Only 40% of those surveyed have a smartphone and only 13% used digital agriculture extension services. Lack of awareness and sound digital literacy, financial constraints, and limited digital capability are key factors that led to low uptake.

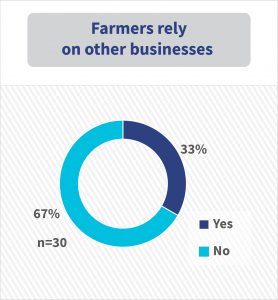

One-third of the farmers surveyed devised additional ways to increase their income by diversifying the sources, especially those who were producing perishable goods. Most of them have relied on existing businesses or other activities like day labor or working on other farms. These additional sources provided them some extra earnings. Laying off agricultural labor is also a common coping mechanism for farmers, which has further enhanced the vulnerability of typically poorer agricultural laborers.

One-third of the farmers surveyed devised additional ways to increase their income by diversifying the sources, especially those who were producing perishable goods. Most of them have relied on existing businesses or other activities like day labor or working on other farms. These additional sources provided them some extra earnings. Laying off agricultural labor is also a common coping mechanism for farmers, which has further enhanced the vulnerability of typically poorer agricultural laborers.