This report provides an overview of the impact of COVID-19 on low- and moderate-income (LMIs) populations, and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), and cash-in and cash-out (CICO) agents, their coping strategies, and recommendations for policymakers and financial service providers to support them. The report was developed from MSC’s research in several countries (Kenya, Uganda, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines).

Bridging the Credit gap for MSMEs: Gaps in access and solutions to bridge the gap

This report estimates the credit gap in the MSME sector as it emerges from the long shadow of COVID-19 and presents solutions to bridge this gap. It presents the current state of financing to MSMEs, including the role of initiatives like TReDS and GeM in meeting the short-term financing gap. It also touches upon supply-side challenges that MSMEs face in accessing credit. The report then offers some broad recommendations and some technology-specific ones with a focus on financial architecture and digital public infrastructure plan for faster diffusion of cash-flow-based lending and deeper access to credit.

Launch of new reports on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cash-in cash-out (CICO) agents, farmers, and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Kenya.

As part of our continued research, we present the second round of reports on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cash-in cash-out (CICO) agents, farmers, and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in #Kenya. Our reports indicate that these segments of the economy have been struggling to overcome the challenges posed by the pandemic despite the reduced hours under curfew and relaxation of restrictions in inter-county movement by the government.

MSC and Swiss Capacity Building Facility(SCBF) launched the new reports on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cash-in cash-out (CICO) agents, farmers, and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Kenya through an interactive webinar on 21st January, 2021.

Agriculture and food security: Leveraging PDS to boost agriculture and ensure food security and diversity

Public Distribution System (PDS) – From food security to nutrition security

Mid-day Meal Scheme : Moving from food to nutrition security

The Government of India (GoI) has done notable work in feeding 115 million children through the Mid-day Meal Scheme (MDMS). It has already made giant strides to reach its first objective of increasing student enrolment and attendance. However, guidelines around the scheme need to improve for the program to reach its second objective of improving the nutrition of the students.

Most decisions regarding MDMS are taken at the national level. However, states play a vital role in the evolution and improvement of the scheme. States have the flexibility to innovate the scheme and the MHRD encourages them to pilot new interventions. States are permitted to use up to 5% of their annual budgets for novel interventions with prior approval from MHRD. Many states have utilized this allotment and further supplemented it with their own funds to achieve a better impact on children’s nutrition and other areas. In the following section, we look at a few examples of such interventions, which we have categorized under infrastructure, nutrition, and monitoring.

Infrastructure

As part of the MDMS, the GoI mandates that all schools have kitchens where meals can be cooked and served fresh to the children.[1] Additionally, the GoI encourages schools to have nutrition gardens[2] as well as toilet and washing facilities.

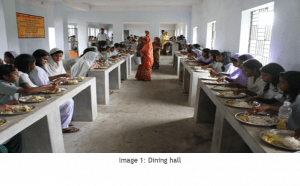

- Some states have gone a step further by providing funds to schools to construct dining halls to improve cleanliness and discipline among students. West Bengal has built 692 dining halls and Tripura has built 250, both with state funding. Madhya Pradesh has also started building dining halls. In Assam, where state funds were not sufficient for such a project, the state provides tarpaulin mats to each school so that students do not have to sit on the bare floor while eating.

The benefit of the intervention: In schools that lack dining halls, students often have to sit in open spaces on bare floors to eat their meals. Eating in dining halls increases hygiene and makes students more eager to participate in the MDMS.

The MHRD advises all schools to have washing facilities but many states cannot afford to construct large enough facilities for school students. Most schools only have one or two taps available as washing facilities. Odisha overcame this problem by installing cost-effective devices made of plastic and rubber with multiple taps running from a tube-well or pipe source, which allows several students to wash their hands at a time.

The benefit of the intervention: This invention saves time, reduces chaos among the children, and increases convenience.

Nutrition

A primary objective of the MDMS is to improve nutrition for children. As India attempts to move from food security to nutrition security, MDMS can emerge as the ideal conduit through which nutritional food can be delivered. Some states have instated policies specifically to utilize the MDMS to improve nutritional outcomes.

In Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Tamil Nadu, governments are piloting fortification[1] of food grains, which are then served as part of the MDM in some districts. The UP government has been fortifying food grains in Varanasi in collaboration with the World Food Program while the Tamil Nadu government is doing it independently.

The benefit of the intervention: The WHO recommends food fortification as a means to reduce malnutrition. By fortifying food grains before serving them to students, the governments of Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh expect to improve the nutritional outcomes of their students.

In Uttarakhand, “apna kitchen, apna bhojan”[2] is organized, under which kitchen helpers teach children to prepare the MDM once a week.

The benefit of the intervention: This teaches students to be responsible for their own food requirements and nutrition while imparting an important life skill for their future.

The Gujarat government has divided the MDM into two meals. As per the guidelines of the MDMS in Gujarat, schools should provide 180 grams of food grains to primary students and 265 grams of food grains to upper primary students. When the requisite food grains are cooked, it expands to a weight that is too much for the primary and upper primary classes to consume at one sitting. Thus, the meal is divided into two meals and served as breakfast and lunch.

The benefit of the intervention: Splitting the meal into two ensures that children eat the complete amount of food grains available. They eat both breakfast and lunch, which ensures that they do not go hungry during the school day.

- The governments of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu have expanded the MDMS to cover children who study in classes 9 and 10. The respective state governments fund this completely.

The benefit of the intervention: Findings of research studies have suggested that MDM has led to increased student retention rates and has played a role in curbing dropouts, especially among girls. By expanding the scheme to Classes 9 and 10, the state governments hope to reap the same benefits.

- The Kerala government provides a separate breakfast in addition to the MDM in approximately 3,000 schools in the state, all of which are state-funded.

The benefit of the intervention: The draft of the new education policy of the MHRD states that the morning hours after a nutritious breakfast can be particularly productive. By ensuring that children receive not only a mid-day meal but also an energizing breakfast, the Kerala government makes sure that students are well-fed throughout the school day, which allows them to focus better on their studies.

Monitoring

Monitoring remains an essential component of any scheme. While all states must comply with the National Monitoring Guidelines for MDMS, including monthly and annual report submissions, certain states and union territories have increased the monitoring component on their own.

- The Chandigarh government has installed CCTV cameras in all kitchens.

The benefit of the intervention: This allows authorities to monitor the kitchens in real-time. It also serves to ensure that the kitchens follow all the MDM guidelines and allows mitigation of any untoward incidents, such as instances where children have reported illnesses after consuming the meal in school.

- Uttar Pradesh has created a “Maa Samuh” for each school, as part of which six mothers visit the schools regularly to supervise the preparation and cooking of the food served to students. The six mothers are selected on a voluntary basis. The central government also encourages states to appoint eligible and interested parents of schoolchildren as kitchen cooks.

The benefit of the intervention: The rationale behind creating the Maa Samuh is that mothers with children studying in the school will have a greater stake in ensuring that the MDM is prepared in a quality manner.

- In Madhya Pradesh, a sample of the day’s meal and milk is stored for 24 hours in a container in the kitchen for parents, school figures, or government authorities to check if they wish.

The benefit of the intervention: This aids in addressing any incidents that may arise from poor quality of food or milk served at the MDM.

General Interventions

Many states have also taken smaller steps to improve their MDM schemes.

- Kitchen helpers are considered important stakeholders in the scheme as they cook and serve the meals to the students. In Uttar Pradesh, the kitchen helpers receive training through an innovative short film, Poshana, which focuses on hygiene, safety, and nutrition. In Tamil Nadu, the state government recognizes the efforts of kitchen helpers by awarding those that have done great work based on hygiene and nutrition parameters.

- Goa and Delhi have assisted overburdened teachers in short-staffed government schools by outsourcing all cooking activities to centralized kitchens operated by self-help groups (SHGs) and non-governmental organizations. Government schools are often short-staffed. As a result, teachers frequently become responsible for not only educating students but also implementing government programs—including the MDMS and the School Health Program. When the MDM is cooked on school grounds, the lead teacher is responsible for buying the raw ingredients for the meal (other than food grains) and confirming that the kitchen helpers are preparing food according to guidelines. The burden of these responsibilities reduces when the cooking process is outsourced to centralized kitchens and delivered to schools.

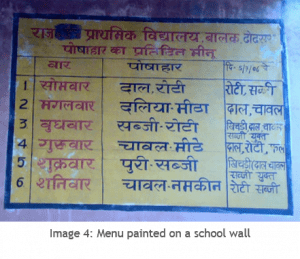

- In Chhattisgarh, the state government mandates that 21 important MDMS-related topics, including the toll-free number to resolve grievances, must be displayed on a visible wall of the school building. This encourages parents to raise grievances if they arise and increases their level of awareness. Other topics include a menu, nutritional and food norms, and details regarding the lead teacher. Additionally, many states paint the weekly MDM menu on walls and bulletin boards in schools. Many MDM interventions initially piloted at the state level became so successful that they were mandated nationally. Existing evidence points to the positive impact of the MDMS on enrolment levels, and the increase in retention and attendance rates of students—one of the scheme’s primary objectives. However, the GoI and state governments should continue to pursue the second, more elusive, goal of improving student nutrition. To do so will require innovative ideas and the ability to test them in real-world situations.

- Each of the steps implemented by the state governments serves as pilots for the idea. The GoI should conduct impact assessments and feasibility studies for each of these innovations and then scale the ones that could potentially have a positive impact on students across the nation.

- States have demonstrated that they are keen to contribute their funds to improve the MDMS. They must continue to experiment to tackle the problem of undernourishment and malnutrition among students as well.

References

In the Indian context, “schemes” refer to programs of varying scale, usually undertaken by the government or private bodies

This is not a requirement for those schools whose food is served from centralized kitchen.

Nutrition gardens are vegetable gardens in the school premises. The GoI recommends their use to teach children how to grow their own vegetables.

Fortification is the artificial addition of micronutrients in food. Read more about food grain fortification on MSC’s blog “How India can move from food security to nutrition security”.

In English: “My Kitchen, My Meal.”

The data is available on the MDM website, which posts findings from various research studies