Fifty-three-year-old Rezwan Kabir (name changed) is a former bus driver who had changed his profession after 20 years. It was 2007 and he felt he was growing too old to manage the grind of driving long distances. He opened a small daily provisions shop in a village market in central Bangladesh. The business gradually picked up and prospered—until COVID-19 struck Bangladesh.

Rezwan struggled with several challenges like supply issues, falling customer footfall, lockdowns, increased price of items, and the constant fear of infection. His income shrank and he had to withdraw most of his savings and put his plans to grow his business on hold indefinitely. Rezwan’s case is just one among the millions of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that faced unprecedented challenges during the pandemic. Many were closed permanently or forced to change their business, as losses piled up.

What surveys told us about the impact of the pandemic on MSMEs in Bangladesh

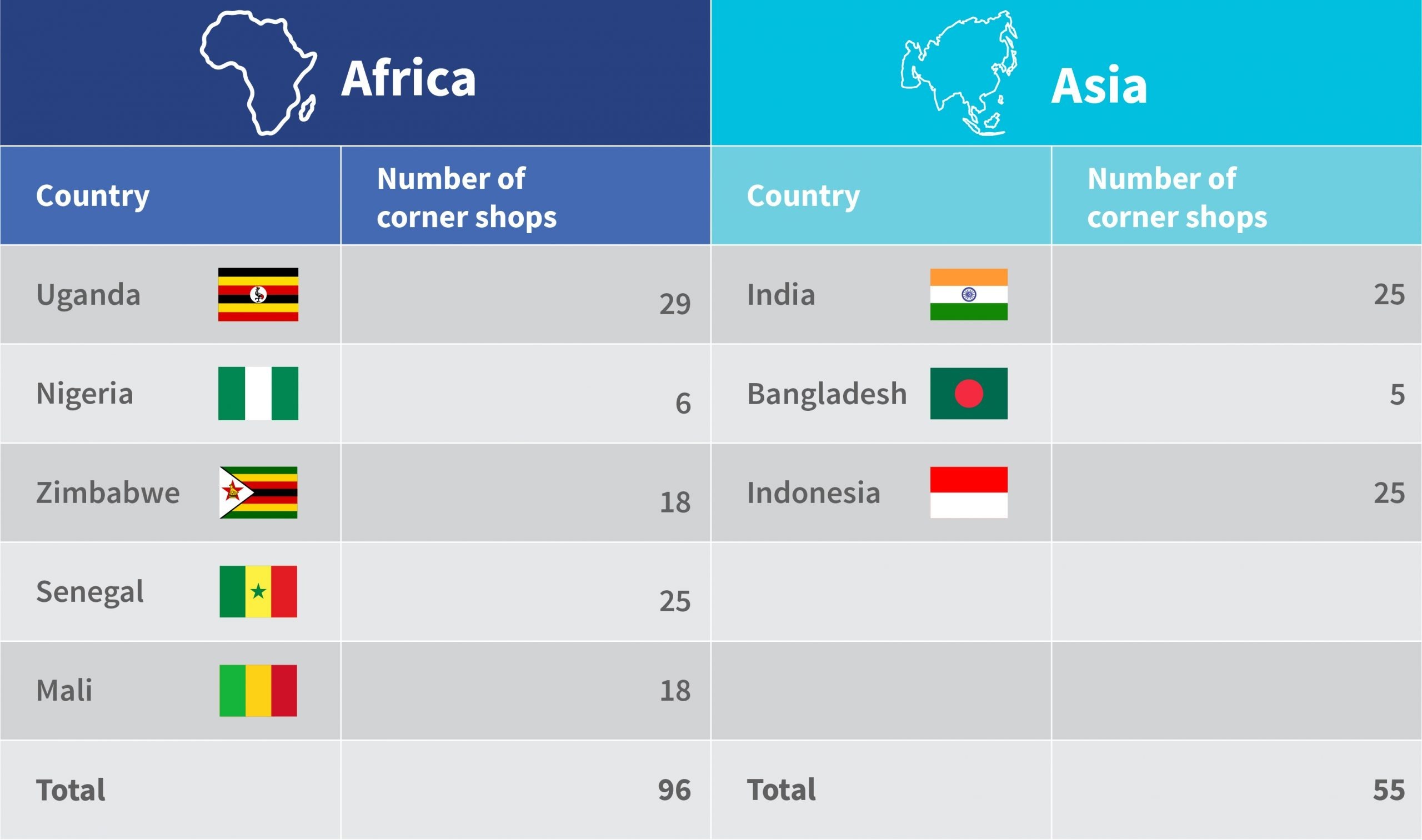

We examined two surveys conducted during the pandemic—MSC’s study of 90 MSMEs conducted in May, 2020 and International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) study of 500 MSMEs in June, 2020.[1] The IFC survey covered a wide range of MSME types, including farm based and non-farm enterprises , wholesalers, retailers etc. The MSC survey sample included a smaller proportion of manufacturing businesses and focused on shops and services.

The MSC study found that customer footfall had decreased for 94% of MSMEs in Bangladesh and sales had fallen for 85% of MSMEs. The pandemic had an impact on the supply chain too: 74% reported decreases in the volume, while 58% reported decreases in the value of supplies. 38% reported that suppliers had stopped offering credit and 28% revealed that they were offering less credit than before. The nationwide lockdown was in effect from 26th March, to 31st May, 2020. The survey was done when the lockdown was still in force and therefore captured the situation at its most severe.

The IFC dataset indicates that 83% of firms were making losses and 21% of them had closed temporarily, either by choice or by government mandate. 91% of the firms suffered from decreased cash flow, averaging around 52%. 67% of the firms were affected by shocks like a reduction in hours worked, reduction in demand, and unavailability of financial services. The survey was done in June, after the lockdown was lifted when economic activity had started to recover.[2]

These one-off surveys revealed the situation of the MSMEs at specific points in time. However, we needed to go behind the survey data to understand how the business owners survived the pandemic and know if have they started to recover, among other developments. To answer these questions, we can turn to other research methodologies like the Financial Diaries. The insights that we get from the data in the daily diaries can give us a more nuanced perspective than those derived from a one-off survey.

Arshad’s story: resourcefulness, resilience, and innovation

For the past five years, the Hrishipara Daily Financial Diaries project[3] has used the diary-based research to track 60 low-income households in Hrishipara, a village on the outskirts of a market town in central Bangladesh. In mid-2020, the project added to the sample five corner shops, which are stores for daily provisions. Here, we discuss the case of one such corner shop to understand its situation during the peak of the pandemic and assess if it has managed to recover. The store is owned by Arshad (name changed), who, along with four other corner shop owners, has been volunteering as a “diarist” since the third week of July, 2020.

He told us that his gross income started to decrease when the lockdown was imposed in late March. It reduced to an average of BDT 60,000-70,000 (USD 709-828) a week. This continued for two months and from June onward, Arshad’s gross income slowly started to climb back up but did not return to pre-COVID levels. During the peak of the pandemic between March to June, 2020, he would open his shop early in the morning when mobility was less strictly regulated by the authorities. Customers could come to his shop to buy their daily needs in these early hours and the arrangement worked for both parties.

He told us that his gross income started to decrease when the lockdown was imposed in late March. It reduced to an average of BDT 60,000-70,000 (USD 709-828) a week. This continued for two months and from June onward, Arshad’s gross income slowly started to climb back up but did not return to pre-COVID levels. During the peak of the pandemic between March to June, 2020, he would open his shop early in the morning when mobility was less strictly regulated by the authorities. Customers could come to his shop to buy their daily needs in these early hours and the arrangement worked for both parties.

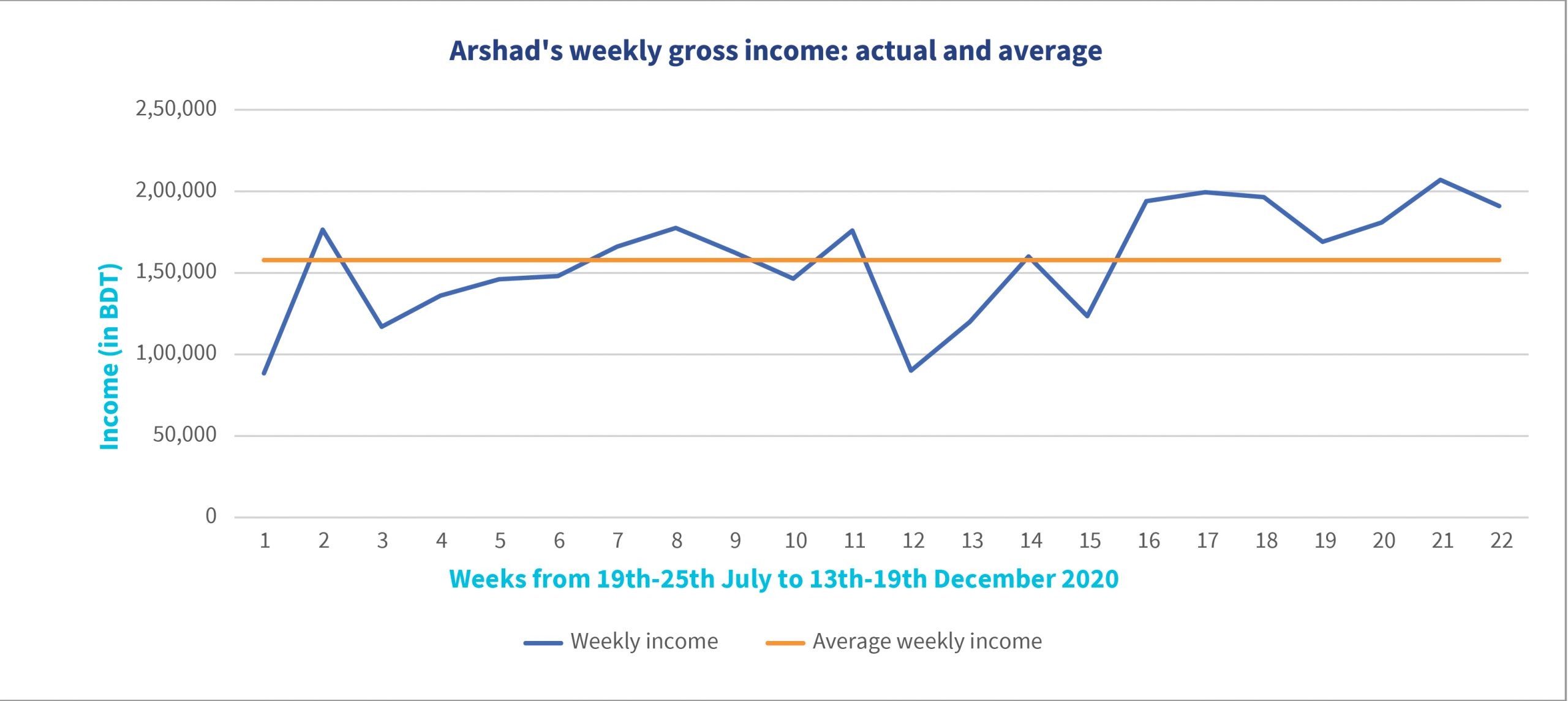

In our first interview with him, Arshad told us he sells grocery items, cosmetics, and airtime from a shop that he owns and has been running for nine years. His shop is comparatively larger than other shops in his area and is situated in a prominent business location. Arshad estimated his weekly average gross income, that is, sales revenue before COVID-19 at BDT 210,000 (USD 2,483)[4].

In Graph 1, we see that the weekly gross income in the first week of data collection was BDT 88,400 (USD 1,045) and the highest income was in the second week of December at BDT 207,000 (USD 2,447). The average weekly gross income throughout the period of data collection was BDT 157,805 (USD 1,866), which was still just 75% of the reported average weekly gross income in the time before COVID-19. The data suggests that sales are slowly getting back on track and the recovery process has started.

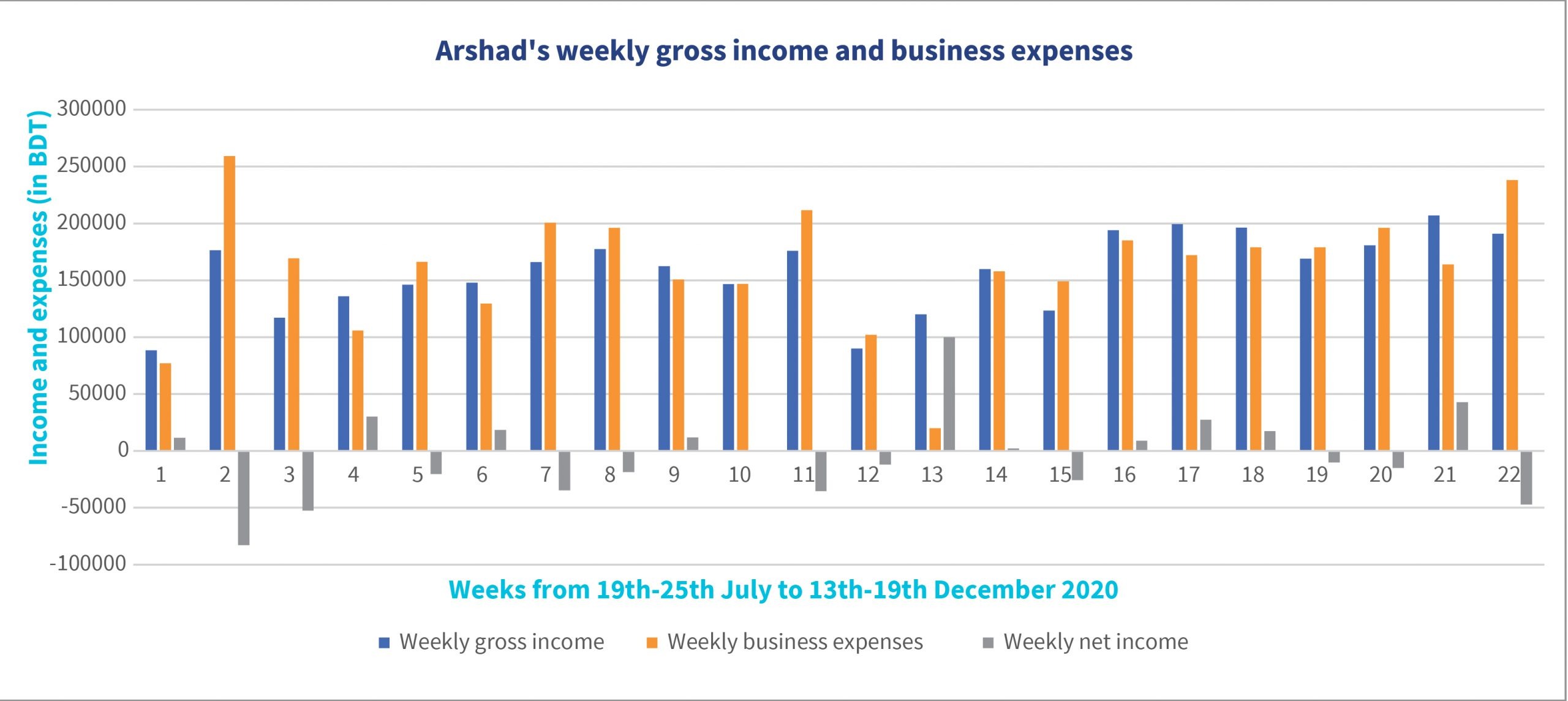

But what do the diaries say? Graph 2 depicts his weekly income, business expenses, and net income. Surprisingly, in more than half of the weeks (12 out of 22 weeks) during data collection, the net income of the week was negative—that is, the business expenses exceeded sales.

However, has he been making a profit? Arshad reported that before COVID-19, his weekly net income was in the range of BDT 14,000-15,000 (USD 165-177). After COVID-19 struck Bangladesh, in the first three months (March to June 2020) he told us that his weekly net income shrank to the range of BDT 6,000-7000 (USD 71-83).

Arshad was fortunate that his household had several regular sources of income, unaffected by the pandemic. This reemphasizes the importance of regular guaranteed income in situations like COVID-19—be it through a secure job or direct cash transfer. Fortunately, both the Government of Bangladesh and BRAC, the largest NGO in Bangladesh, ran cash transfer programs for the poor in the country and these programs helped millions of households to survive the pandemic.

How did he manage his household expenses in these tough times? Like many low-income households, Arshad has more than one stream of income. His wife is a government high school teacher, and her income takes care of some of the family expenses. Arshad’s household is part of a joint family—he lives with his elder brother’s family. One of his nephews works in Singapore and the remittances he sends helped the household during the peak time of COVID-19 and even now.

The pandemic has not changed the way Arshad runs his business. Operating the business in the early morning hours was a temporary coping strategy and Arshad discontinued this once the lockdown was eased. He chose not to digitize his business operations. His customers mostly pay him in cash, and most people in the locality do not have the means to buy digitally.

Among the 60 diarists of the Hrishipara Diaries project, none has a debit card, credit card, or other means to make digital payments. Though some use mobile money services (MFS), they do not use it to purchase goods at shops. In his dealings with suppliers, Arshad rarely uses DFS for payment because the suppliers, who must pay fees to withdraw the payments see it as an expensive option.

So, what do we learn?

- Arshad’s case highlights how bookkeeping and business training could help micro-businesses run more strategically. Not tracking income and expenditure carefully proves to be costly. Digital platforms to train micro-enterprises might help, but need to be complemented by capacity-building and by the adoption of digital systems by the low-income households that constitute Arshad’s customer base.

- A source of regular fixed income, in any form, is immensely important for a household’s financial health, especially in a time of crisis like COVID-19. Direct benefit transfers to the MSMEs (both formal and informal) by the government can help them maintain the financial health of their businesses.

- A continuous flow of nuanced data is needed to inform policy. In this regard, the Financial Diaries approach can be critical to the path toward recovery.

[1] The IFC survey sample was a mix of micro (65%), small (27%) and medium (8%) enterprises. A sample frame was prepared by collating lists of MSMEs from various sources and then sample was drawn using simple random sampling.

[2] See for example, the data on the Hrishipara Diary Project’s coronavirus page at https://sites.google.com/site/hrishiparadailydiaries/home/corona-virus

[3] The project is being funded by L-IFT since 1st June 2019

[4] 1 USD is equivalent to 85 BDT.