Free or highly subsidized power to farmers in India has led to overconsumption of groundwater by the agricultural sector. The situation has reached a near-crisis level in many states due to these high subsidies. Unique models like Paani Bachao, Paise Kamao (Save water, earn money), the Direct Benefit Transfer in Electricity (DBTE) introduced in Punjab, offer a politically feasible and effective solution to the persistent issue of overuse of groundwater

Energy-water-agriculture linkages

‘Surviving a pandemic’: Five key insights from the Corner Shop Diaries research in India and Indonesia

Ishwar Sharma, the only bread earner in his family, runs a small café in a town in northern India. Meanwhile, Alus, a mother of two, runs a small grocery store in Central Java, Indonesia.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the “economic pandemic” that followed have brought Ishwar and Alus to the same point. These misfortunes had hit the businesses of both micro-entrepreneurs badly.

In Ishwar’s case, people become reluctant to buy his food and beverage due to health concerns, as he prepares the items he sells onsite. His troubles were compounded by the prolonged closure of businesses during lockdowns, which translated to fewer customers, alongside new competition from the reverse-migration by people returning from the cities who set up small cafes in his neighborhood.

As for Alus, her customers—mostly local farmers—became cash-strapped due to the significant drop in crop prices. Furthermore, the prices for basic groceries have surged during the pandemic (for instance, the price for cooking oil jumped 33% higher), and Alus’ customers had to either limit their purchase or pay for their groceries later.

Both micro-entrepreneurs are, however, striving to keep their businesses afloat.

MSC’s research on the impact of COVID-19 on MSMEs in India indicates that 73% of the businesses surveyed had reported a decrease in customer footfall. Meanwhile, three-fourths of the enterprises reported a decline in income. Meanwhile in Indonesia, 79% of MSMEs surveyed reported a drop in sales volume by a median of 50%; and 51% reported that they kept operating as usual but the overall number of customers per day had decreased by a median of 50%.

From October, 2020, MSC started to track the daily financial life of 25 corner shops each from India and Indonesia using the Financial Diaries methodology. We have collaborated with the social enterprise Low-Income Financial Transformation (L-IFT), to track the daily financial transaction of corner shops. These corner shops are small retail businesses located in neighborhoods that sell daily needs products and provide essential services.

The daily financial data of these shops generate intriguing insights into how these corner shops are in the process of recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic and the challenges they face.

In this blog, we discuss five insights from the early data of this research.

- In India, owners of the small daily provisions store have become risk-averse and restricted their ambition.

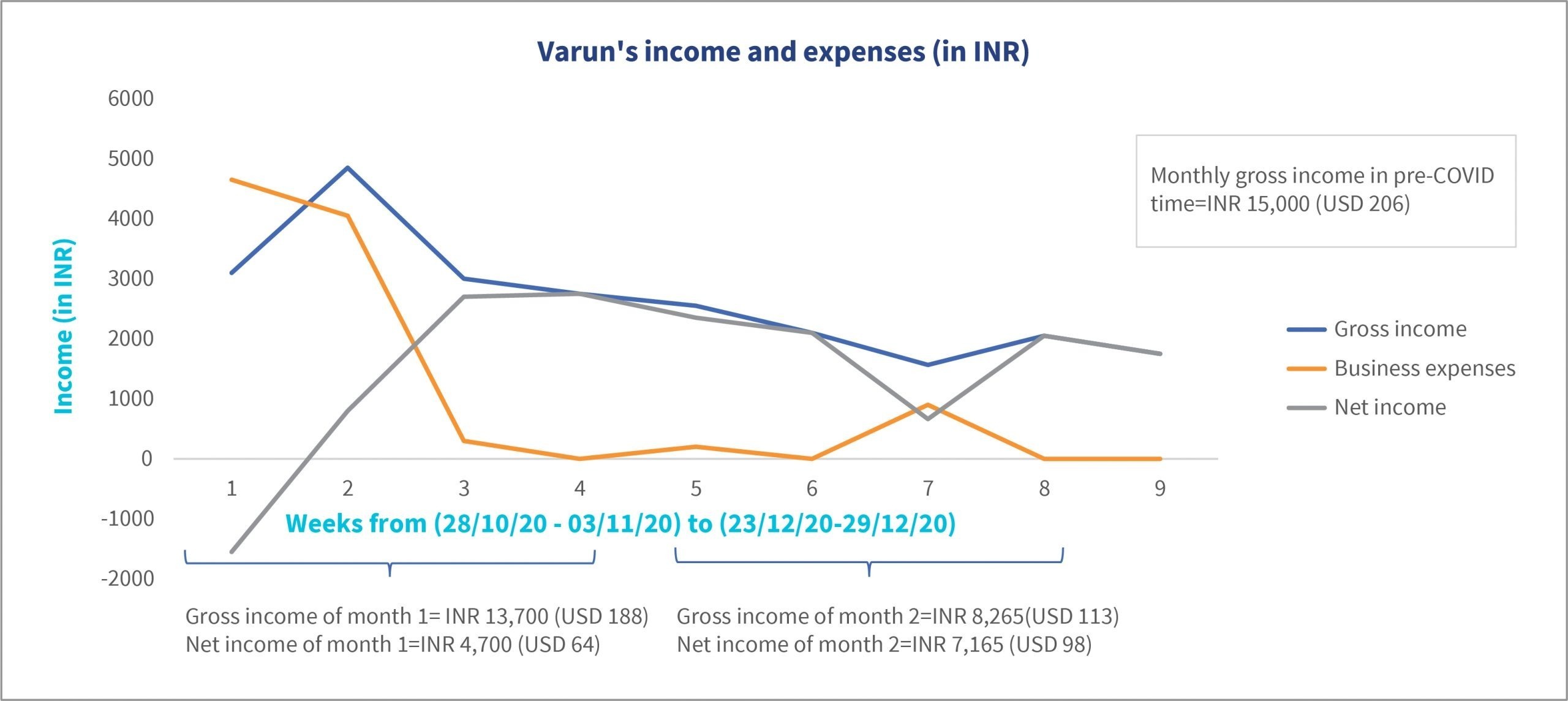

Varun Singh, father of two teenagers, runs a small daily necessities store in the north-west part of India. He mentioned during the interviews that his monthly gross income was INR 15,000 (USD 206) per month before the pandemic, which dropped to INR 8,000 (USD 110) per month during the pandemic.

Varun Singh, father of two teenagers, runs a small daily necessities store in the north-west part of India. He mentioned during the interviews that his monthly gross income was INR 15,000 (USD 206) per month before the pandemic, which dropped to INR 8,000 (USD 110) per month during the pandemic.

The data that we collected in the past two months of 2020 indicates that he is yet to attain his pre-COVID level of business (see Graph 1).

Graph 1

Varun has been running his small shop from home although he wanted to buy or rent a shop in the market area. Despite difficulties, he wanted to grow his business. Yet the financial and health-related risks related to the pandemic have convinced him to postpone his planned expansion and continue operating from the current location.

Many corner shop owners in our sample also think along similar lines. Even though customer footfall has returned to normal, they are buying less compared to pre-COVID-19 times. Hence even if the income of the shops has picked up gradually, is still not what it used to be.

The financial stress and the experience of losing near and dear ones have made the corner shop owners risk-averse.

- In Indonesia, many corner shops managed to maintain their regular income during the pandemic. For some, the pandemic helped to increase revenue.

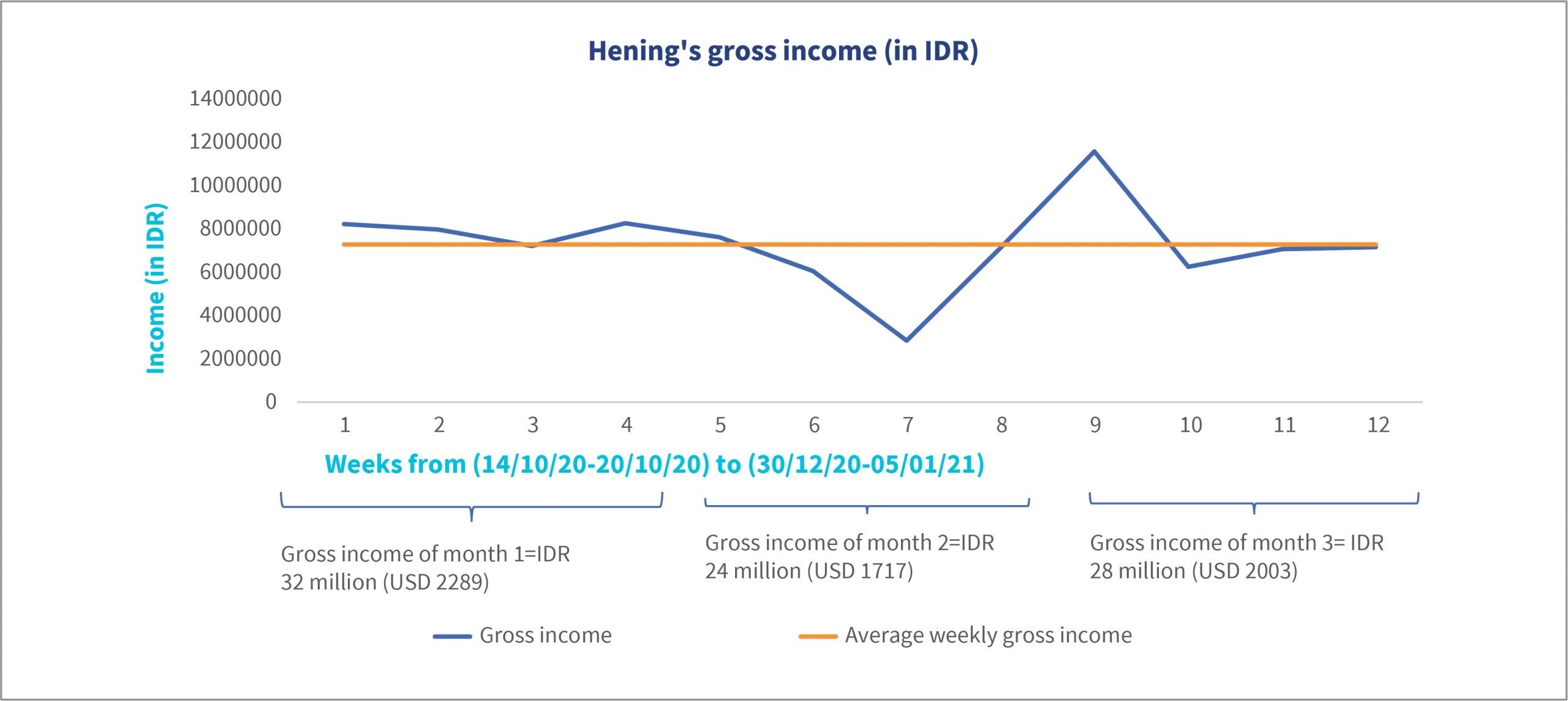

Hening, a young mother of two, runs a corner shop in Central Java. She sells staple foods, cooking oil, snacks, sweets, tobacco and cigarette, medicine, gas, and toys. She could maintain her usual sales revenue even during the pandemic (an average of IDR 30 million or USD 2,146 per month).

Hening, a young mother of two, runs a corner shop in Central Java. She sells staple foods, cooking oil, snacks, sweets, tobacco and cigarette, medicine, gas, and toys. She could maintain her usual sales revenue even during the pandemic (an average of IDR 30 million or USD 2,146 per month).

The data from the Diaries (Graph 2) indicates that Hening’s average monthly gross income is IDR 29 million (USD 2,074). It shows a drop in November, 2020 (Week 7) but only because Hening had to close her shop for around two weeks to help with some wedding events.

The revenue of Hening’s shop was soon back to normal—and even increasing—once she returned to the business (see Graph 2).

Hening has maintained her sales revenue during the pandemic by using some simple strategies. For instance, she stopped selling airtime as many of her customers often pretend they didn’t receive the top-up so they can refuse to pay –forcing Hening to cover the cost herself. As Indonesia did not restrict shop operational hours, Hening also kept her usual opening hours, that is, 6 am to 9 pm daily during the lockdowns. She also implemented hygiene protocols when the pandemic was at its peak by providing hand sanitizer outside the shop for customers’ use to make them feel safe.

Moreover, Hening has started to prepare better budgeting for her business and personal finance. She also uses her business data to map her income and expenses better and also allocated some money for saving.

Graph 2

Many corner shops in our sample adopted several simple strategies. These included following health protocols to make customers feel safe, prolonging operational hours to increase customer footfall, and reducing the number of staff members. The corner shops also adjusted their product or service mix to sell items in high demand or commanding a higher market price and stopped the sale of unprofitable or less-profitable items.

The strategies have helped corner shops to maintain their income or even make more profit than in earlier years.

- Corner shop owners are beginning to think digital.

In India, multiple corner shop owners, such as medicine shops, barbers, and cafés, among others, told us during interviews that they have started to accept digital payments, most commonly from PhonePe or Google Pay from clients during the pandemic. This phenomenon is mostly observed among younger diarists. We have also seen the use of messenger apps and social media to market products and services. Some diarists have also started to accept orders from regular customers through WhatsApp.

In Indonesia, we found multiple diarists using their WhatsApp and Facebook accounts to promote their business; mostly to generate awareness among customers about any new product or service they have started to sell. We also found that the micro-entrepreneurs use WhatsApp to communicate with suppliers. Some diarists use e-commerce sites, such as Shopee, Tokopedia, or Bukalapak to buy stocks at cheaper rates and sell specific products, such as plastic furniture. Only two of our diarists use digital payments to settle bills through ShopeePay, and pay suppliers and accept payments from customers through OVO and LinkAja. However, this had been their practice for a couple of years before the pandemic.

Many diarists were interested in using e-commerce in the future. Yet juggling between the brick-and-mortar shop and the online store requires time and energy. They also have concerns about the cost of internet data; hence they have become reluctant.

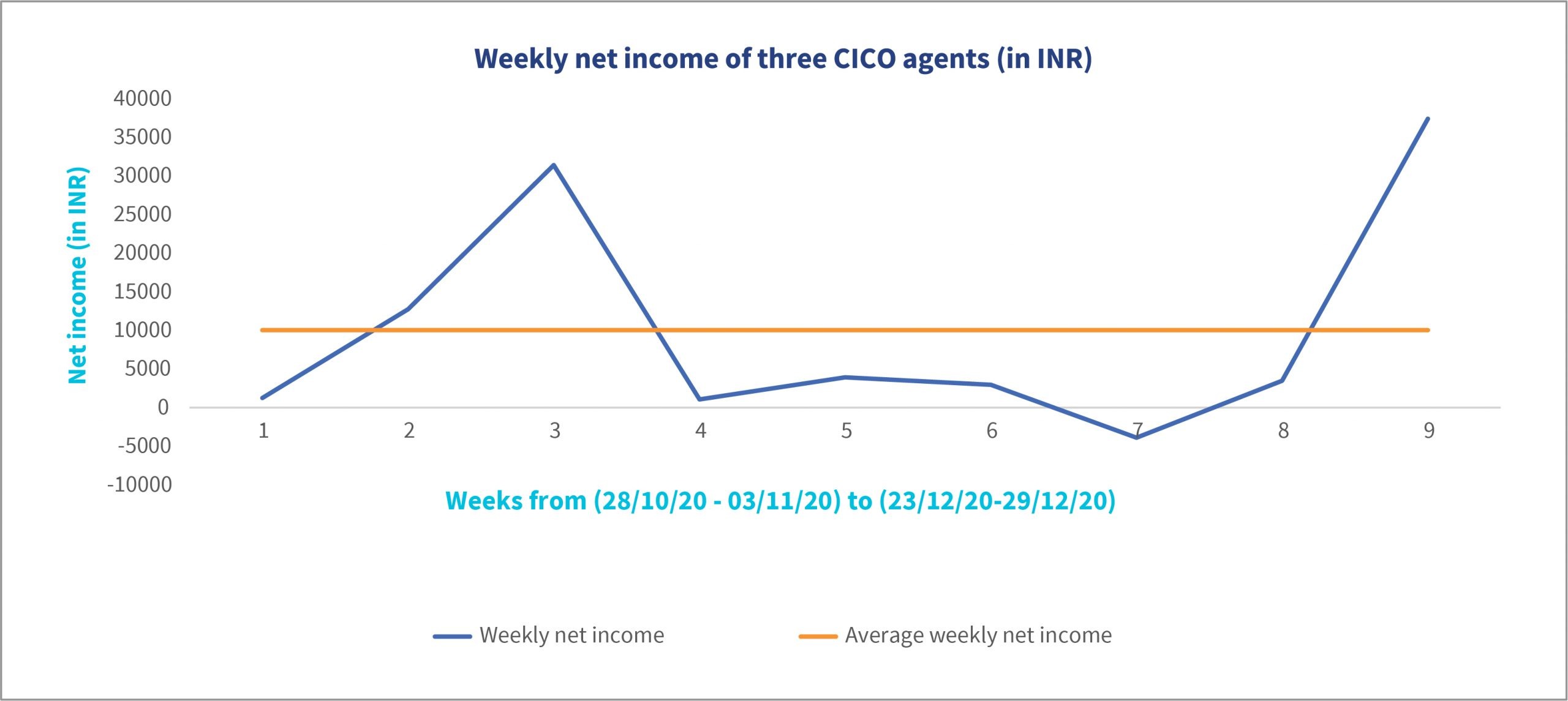

- CICO agents in India saw increasing footfall but declining income during the lockdowns.

Our sample from India has three dedicated CICO agents and all of them mentioned that the pandemic has hit their businesses. These three CICO agents reported the total monthly net income of INR 38,000 (USD 521) before the pandemic, which fell by 24% to INR 29,000 (USD 398) during the pandemic.

The four major reasons for the decline in income are:

- Reverse migration, which has decreased remittance;

- Most withdrawals were small in value, which increased footfall but not income;

- Worrying about cash crunch during lockdowns, many people withdrew their savings through the BC agents, thus creating liquidity issues for the agents;

- Owing to mobility restrictions, agents could not travel to rebalance their liquidity, which also hampered the business.

Graph 3

However, the business has picked up now. Graph 3 shows the average monthly income of INR 40,108 (USD 550), which is similar to pre-COVID-19 times.

- Women who own corner shops have faced unique challenges during the pandemic.

Social norms and caregiver responsibilities created an extra set of challenges for women who own corner shops. As traditional gender roles are still prevalent, we observed our women diarists struggle to manage their unpaid work at home and responsibilities at the shop.

One respondent from Indonesia mentioned that as schools are closed and children are at home, she struggled to manage her shop and the children. For another respondent, the extra pressure of earning for the household, since her husband lost his job, and fulfilling her duties as the caregiver made her life very stressful.

In India, a few women-owned enterprises reported that their husbands used to help them for tasks where mobility is required, such as withdrawing cash, repairing business assets, and buying supplies, among others. Yet the COVID-19 pandemic posed a challenge as their husbands had to work harder to earn money and could not help at their wife’s business.

To conclude, we highlight that financial conditions and the adoption of digital means are dynamic processes that change rapidly. One-off surveys can capture the situation at one point in time but fail to capture the transition and the volatility. Fortunately, the Corner Shop research can bridge this knowledge gap.

This blog is an introduction to the Corner Shop Diaries project, the first of a series that will be published regularly this year. We will also publish regular data-based insights on our website, and combine these insights with actionable recommendations for policymakers and practitioners.

This series will touch upon different themes, including the adoption of digital payments and e-commerce by micro-businesses, savings and loan products that they need, and their behavioral changes over time. Be sure to stay updated for more insights from us.

Volatility and resilience: Lessons from the corner shop diaries research in Nigeria

Adaeze Degreat, a middle-aged mother of two, works in a local teaching hospital in Southern Nigeria and runs a supermarket that sells groceries and daily provisions. A steady income from her salary and a variable income from her shop keeps Adaeze’s household finances mostly manageable. That is, until COVID-19 hit Nigeria. The disease was first reported in the country on 27th February, 2020. By April, several states in the country were under a complete lockdown, barring essential service providers, such as medical facilities and grocery shops.

The virus struck communities and upended people’s lives in an unprecedented way, affecting their economy in particular. Different states implemented lockdowns during March-June, 2020. The baseline data of the National Longitudinal Phone Survey, which was collected in April-May, 2020, indicates that 35-59% of the households that needed staple food could not purchase it, 26% of the households could not access medical treatment, and the income of 79% households decreased.

As highlighted in this report by FATE Foundation, the pandemic had a severe impact on MSMEs. 94% of MSMEs reported being negatively impacted by the pandemic—particularly in the areas of cash flow (72%), sales (68%), and revenue (59%). However, corner shops, which are small neighborhood shops that sell daily need items were allowed to operate during the lockdowns and they served as the sole lifeline for local people.

L-IFT had been running a Financial Diaries research exercise in Nigeria since 2019. In that sample, we identified five corner shops and later included a sixth shop in April, 2020 for the global Corner Shop Diaries research. All these corner shops are located in the Edo State in Southern Nigeria. By the end of March, Edo State had started lockdown measures by limiting public gatherings to 20 people. By mid-April, a full lockdown was in effect, backed by containment strategies, such as closures of all interstate borders.

Using the daily financial transaction data from the diaries, our blog provides key insights about the financial life of corner shops and the impact of COVID-19 on them.

- The COVID-19 pandemic had a severe impact on the income of corner shops, which was already volatile

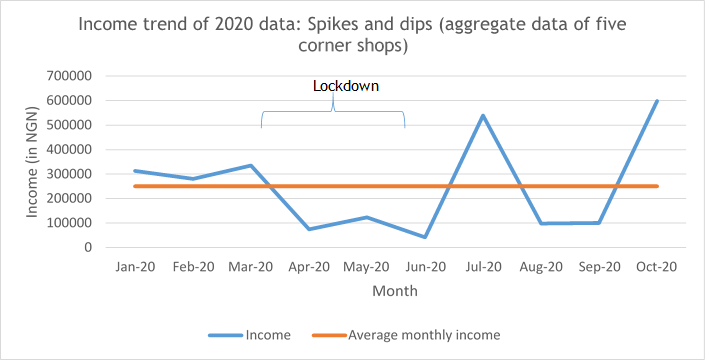

The five corner shops in our pre-COVID sample vary in terms of the businesses they operate but all display similar volatility in income. Three corner shops sell groceries and daily provisions, one is a crayfish business, and one is a digital services shop. Examining the trends in the income of these shops in 2020 (Graph 1) highlights the volatility.

For five out of the 10 months, the combined monthly income for the five corner shops was more than 25% below their overall average monthly income—we can call these dips. The monthly income for three months was 25% more than the average monthly income—we can call these spikes.

We also see how external factors, as well as business-specific nuances, can affect income. The crayfish business, which started in January, 2020 has been very profitable and has seen big cash flows in regular intervals. The spike in July is mostly due to one such big cash flow. The second spike in October a result of panic buying by people as they feared a shortage of items caused by the END SARS people’s protest.

Graph 1

Graph 1

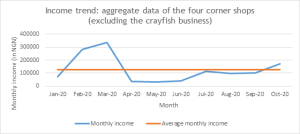

If we zoom in on the data from March to June in the early months of the pandemic, the impact of the lockdowns is prominent. As we can see in Graph 1, during the lockdowns, that is, April-June 2020, the income of the corner shops was at its lowest point. The crayfish business, which performed well during some stages of the lockdown, created the combined income spike in July 2020. Graph 2 highlights that the other businesses did not reach their pre-COVID level yet and even the panic buying during the END SARS protests in October did little to help them.

Graph 2

- Depending on additional income sources, rationalizing expenses, and withdrawing savings were key survival strategies for corner shops during the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the importance of multiple sources of income for a household. We saw that our respondents either picked up additional sources of income or started to depend more on their secondary sources of income. One of the respondents, who holds a salaried job, happened to have started the lucrative crayfish business just before the pandemic in January, 2020. She is the highest earner in terms of overall income among the corner shop diarists.

The respondent started this business after realizing her fixed employment was no longer enough to survive. This proved lucky for her. During the lockdown, which limited operating times at her workplace, shifts were implemented. Meanwhile, her salary began to diminish. She also offered crayfish deliveries during the lockdown, since she owns a car. Through this venture, she could reach more customers quickly and provide a convenient solution for them, who stayed at home to avoid COVID-19. The income from this crayfish business helped her to manage her finances at the peak of the pandemic.

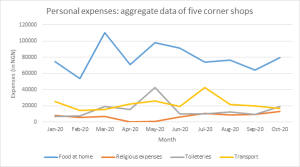

Graph 3

The expenses of the corner shop owners (Graph 3) helps us understand some of the coping strategies they adopted and how their expenses changed during the pandemic. We can see an increase in expenses on food in March, which can be attributed to pre-lockdown panic buying of essentials. We then see a drop in April, when the lockdown was in full swing, and then a rise in May as lockdowns eased up. This gradually came back to the pre-COVID levels by September-October.

Understandably, we see a drop in religious expenses in April – May. This was the time during or just after the lockdowns and mosques and churches were closed. Although the lockdown eased slightly from May, the post-lockdown era came with its own new set of regulations with bans on religious and social gatherings still in place. However, around October, religious expenses seemed to have exceeded pre-COVID-19 levels.

Owing to the lockdowns, when nobody was permitted to travel, transport costs dipped during March. The month of May saw the gradual easing of lockdown restrictions, which allowed people to move and work again. Hence, we see a sharp increase in transport costs followed by a gradual stabilization and then further increases with further easing of the lockdown.

The cost of toiletries rose just after the lockdown (see the spike in May) as personal hygiene measures were a priority for most. Since toiletries, such as soaps and sanitizer were important for COVID-19 prevention and care, some shops bought and hoarded them in anticipation of their demand. However, during the June to August period, we see toiletry expenses dropping as a result of lower demand and an expectation for them to return to pre-COVID-19 levels.

The pandemic also forced the diarists to withdraw significantly from their savings. Data from the five corner shops—excluding the one that joined in April, 2020— indicates that the total savings withdrawn by respondents increased significantly between April-October, 2020 compared to August 2019-February 2020. The respondents reported that they withdrew NGN 354,000 or USD 928 in April-October, which is 66% more than their withdrawals in August 2019-February 2020. The crayfish business and a supermarket contributed the most in this owing to the increase in demand and the subsequent need to restock.

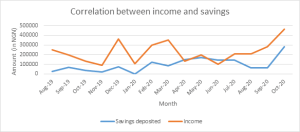

- The savings patterns of corner shop owners correlate with their income

Graph 4

Graph 4

We observed that income and savings are correlated (correlation coefficient=0.5). Graph 4, makes it evident that the pattern of people making savings deposits mostly mirrors their income patterns. The only exception is in March, 2020, the month when lockdown started. This dip in March is likely due to the limited amounts that could be saved during the start of the lockdowns as businesses and their individual households needed more funds to stock up adequately for the COVID-19 period. During this time of uncertainty, people may have also preferred to keep their money in cash, ready for use, instead of saving the money.

Closing remarks

The findings highlight the reality of income volatility and celebrate the resilience of micro-businesses and LMI segments. Many observers expect the business of corner shops to remain unharmed as they were allowed to operate during lockdowns. Yet this is clearly not the case. They faced significant drops in income and have only gradually started to recover. We also see how multiple sources of income are extremely helpful during times like the pandemic. Adaze, who we met at the beginning of this blog, received substantially less income from her salaried job and her business also suffered due to reduced customer footfall. However, she and her business, along with many others like her in Nigeria survived in the long run and have been gradually recovering from the shock. And we can credit a nuanced research approach like the Diaries method to have uncovered a better understanding of the path toward recovery.

The corner shop diaries project: Experience from India and Indonesia

Workshop on Digital Transformation of Postal Operators: Massive outreach, opportunities and challenges

MSC (MicroSave Consulting), conducted a workshop on Digital Transformation of Postal Operators: Massive outreach, opportunities and challenges on the 24th of February, 2021.

This webinar was designed to promote thinking and action on the digital transformation of postal operators in order to leverage their outreach to deliver real financial inclusion. It focused on three aspects:

- The opportunities and competitive advantages enjoyed by postal operators;

- The challenges postal operators have faced or are likely to face as they digitize; and

- The various business models for postal operators.

The webinar had an eminent panel comprising CXOs of postal operators, the UPU and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to discuss these opportunities and challenges.