Strengthening the digital ecosystem: Expanding the adoption of Quick Response Code Indonesian Standard (QRIS) among MSMEs in Indonesia

by Louie Cepe, Ira Aprilianti and Alfa Pelupessy

Jul 5, 2021

7 min

In 2019, Bank Indonesia launched the Quick Response Indonesian Standard (QRIS) solution as part of its payment system vision for 2025 to encourage Indonesia’s 65 million MSMEs to adopt cashless payments. This blog explores challenges in the implementation of QRIS and offers recommendations to improve its uptake in Indonesia.

“The application process is just too complicated, and I struggle to explain it to my customers.”

– A female QRIS merchant in an urban area

One of the key pillars of a booming digital economy is a low-cost and inclusive payments infrastructure. Countries like Brazil, India, and Bangladesh have launched their respective interoperable payment solutions based on the quick response (QR) code to bring small businesses into the digital payments ecosystem. These initiatives have yielded positive outcomes and helped policymakers scale up digital payments from small and micro-enterprises, a segment that forms the backbone of any developing economy.

Indonesia, too, has adopted a similar path and made rapid progress in implementing an interoperable payment system based on QR code

In 2019, Bank Indonesia launched the Quick Response Indonesian Standard (QRIS) solution as part of its payment system vision for 2025. QRIS establishes uniform QR standards to encourage Indonesia’s 65 million MSMEs to adopt cashless payments, with the ultimate objective of universal cashless payments.

With the introduction of the QRIS solution, Bank Indonesia also fixed the Merchant Discount Rate (MDR)[1] at 0.7%—a major improvement from the previous practice of determining MDR through negotiations between individual merchants and service providers.

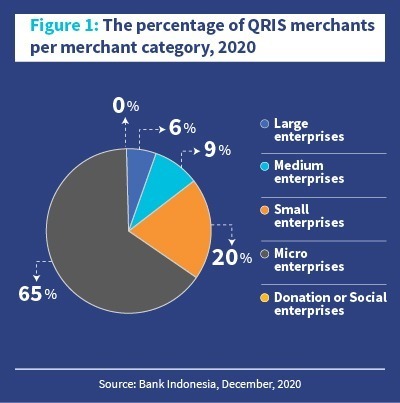

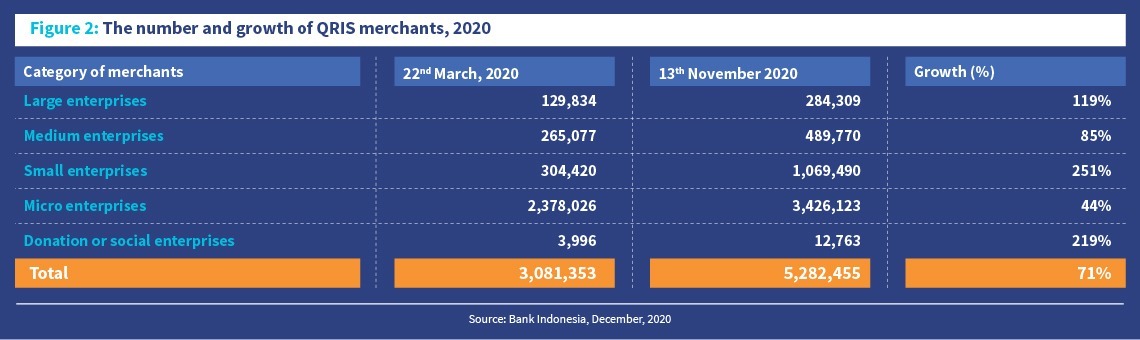

Within a year of its launch, QRIS merchant sign-ups in Indonesia have seen massive growth. As of 2020, 5.3 million merchants had signed up for QRIS. MSMEs contributed to 80% of these sign-ups. Figure 1 depicts the breakup of these merchants according to their category.

While microenterprises account for the highest number of sign-ups of the QRIS solution so far—small, medium, and large enterprises registered much higher growth in terms of overall sign-ups for the solution (as shown in Figure 2). This trend may reflect the higher levels of awareness and digital capacities of SMEs. Moreover, the customer base of SMEs comprises more individuals from the low- and middle-income segments in urban geographies These customers already use mobile-based payment likely to adopt alternative channels.

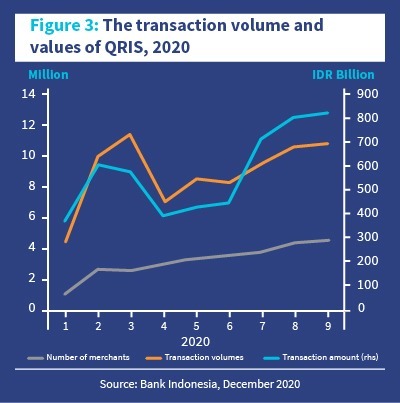

Despite a remarkable growth in the number of merchant sign-ups, the adoption rate of QRIS-enabled payments remains low

Our recent study on CICO agents in Indonesia shows that an active QRIS merchant performs around 14-17 transactions per month. However, data released by Bank Indonesia suggests that, on average, a QRIS merchant conducts about three transactions per month. Anecdotal evidence indicates that a large majority of merchants remain dormant.

What are the reasons for the low adoption of QRIS among MSMEs in Indonesia?

Lack of awareness and low digital literacy

Dalberg’s multi-country study on small merchants highlights that in countries that digitalized their payment landscape , merchants who reported having insufficient information were less likely to use digital payments. This also holds true in the case of Indonesia. MSC’s MSME study shows that 65% of MSMEs were not aware of the QRIS solution, and only 4% of them used it for their business. Further, our recent study revealed that most micro-enterprises in Indonesia have limited access and capacities to conduct digital transactions, such as QRIS. People in non-metro locations and from low-income segments need more time to adopt QRIS. Moreover, qualitative data from our study suggests that the support staff of financial service providers (FSPs) shared little to no information on QRIS with merchants. A possible reason for this is the lack of incentives for FSPs to promote QRIS—due to the interoperability of QRIS, any FSP can push its service to a merchant regardless of who onboarded the merchant to QRIS.

Lack of value proposition

A study by Dalberg revealed that micro and small merchants prefer to pay their suppliers and employees in cash and experience little or no demand for digital payments from their customers. Our study reinforces this finding—68% of MSMEs in Indonesia did not use any medium for digital payments, such as QRIS to accept payments from customers since the pandemic started. MSMEs claim that their customers do not use the digital payment solution, which makes QRIS payments irrelevant for them. Insights from DataReportal support this claim—while nearly half of the country’s population has an account with a financial institution, only 3.1% of Indonesians have a mobile money account. People who use e-money accounts are primarily youth who reside in urban centers and use mobile money for ride-hailing and e-commerce payments. The penetration of e-money remains limited in peri-urban and rural areas.

A complicated sign-up process and lack of provider support

In our MSME study, 17% of merchants reported that they find the QRIS sign-up process too complicated. For instance, merchants need to provide numerous details during onboarding. This makes the process cumbersome and overwhelming, especially since providers lack field staff to assist merchants. Moreover, the process is prone to errors. Even a slight difference in the name of a merchant’s shop can also lead to the issuance of a different QR code. Several merchants reported that they received little support from their providers to resolve queries on operational processes, such as transactions, settlement, and customer grievances.

Sensitivity to Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) charges and fear of disclosing revenues to taxation authorities

The perception of merchants about the impact of QRIS on their manner of doing business affects their decision to embrace the payment solution strongly. Similar to other geographies, merchants in Indonesia are sensitive to transaction charges . Despite Bank Indonesia’s efforts to reduce charges and waive MDR for QRIS, merchants still hesitate to pay for the solution and fear that MDR would eventually dent their thin margins. Moreover, merchants perceive that the potential increase in digital transactions could make their revenues more transparent and traceable for authorities, which would subject them to further taxation.

The way forward: Steps to improve the adoption and uptake of QRIS-based transactions in Indonesia

Increase awareness and enhance digital capacities among MSMEs

The government and financial service providers (FSP) must focus their campaign and training efforts on areas that have a higher penetration of mobile banking and e-wallets, and target merchants who show higher potential and willingness to offer digital payments. MSC’s merchant segmentation framework can help achieve this objective. FSPs need to determine opinion leaders among merchants who can be positioned to educate, motivate, and assist customers during their “teachable moments,” such as instances when customers use QRIS. These opinion leaders can influence other merchants and customers within their communities. The government must equip the targeted micro-enterprises with sufficient knowledge of QRIS, encourage them to gain first-hand experience with the solution, and help them build confidence, trust, and awareness. Training initiatives similar to Gojek’s Wirausaha program, conducted in a workshop setting with audio-visual tutorials and live demonstrations on QRIS can help MSMEs understand its processes and benefits better. The government needs to collaborate with the private sector to enhance awareness of digital solutions, especially in peri-urban areas around big cities.

Enhance the value proposition for QRIS payments

QRIS solutions are traditionally enabled through the merchant presented mode (MPM) or customer presented mode (CPM), which require physical transactions at the merchant point. However, with the risks associated with physical transactions during a pandemic, QRIS needs alternatives to face-to-face transactions that allow merchants and customers to send QRIS payment codes over online channels. This would offer a value proposition on par with bank transfers, the primary digital payment option used by most SMEs. China has expanded the use of QR payment by promoting the use of social QR codes to gift “red envelopes”[2] during the Chinese New Year.

Increase the potential use-cases and value creation for QRIS

FSPs and policymakers should move beyond cashback and person-to-business use-cases of QRIS, such as bill payments, and assess the potential demand for digital payments to realize the full potential of QRIS as a digital solution. The government can provide an option of contactless authentication for government-to-person (G2P) initiatives, such as social payments. For instance, countries like Bangladesh, China, and Thailand opted for digitalization to enable safe and cheap transactions at the height of the pandemic. Moreover, the government can also use QRIS to encourage person-to-government (P2G) payments, like India used its BHIM UPI QR code to accept donations under the PM CARES Fund.

The government must also consider providing incentives, both for FSPs and merchants, to drive the uptake of QRIS. It can learn from the example of India, which has allocated funds to provide incentives to promote digital payments. In Singapore, hawkers who sign up for SGQR are eligible for a monthly bonus under its Hawkers Go Digital Program. Moreover, Bank Indonesia must continue to waive the MDR, especially in the initial phase of the implementation of QRIS to make it more attractive among merchants.

Simplify the sign-up process for merchants and provide better support

FSPs must make QRIS easier to use for merchants and help them gain and sustain confidence. FSPs should establish fully digital sign-up options similar to the Faspay and DOKU registration facilities so that merchants do not miss out on regular business during the sign-up process. They must also provide support to merchants. FSPs can learn from the example of Singapore’s “digital ambassadors” who help stallholders set up the SGQR code and application on their mobile phones during sign-up.

Conclusion

QR codes have helped countries bring a range of excluded segments, such as MSMEs into their digital payments ecosystem. As Indonesia continues to expand QRIS to 12 million MSMEs and support its national economic recovery program, it will need to continue collaborations and introduce targeted interventions. Further research to understand and address the finer nuances of challenges that the demand and supply sides face in adopting and implementing QRIS is crucial to get full support from all stakeholders and reach the potential of the initiative. As the adoption of QRIS accelerates, policymakers and regulators will also need to focus on ensuring data privacy and enhancing consumer protection.

[1] The cost incurred by merchants for payment processing services

[2] Red envelopes or red packets are a long-standing fixture of Chinese New Year celebrations wherby adults usually gift money to young relatives.

by

by  Jul 5, 2021

Jul 5, 2021 7 min

7 min

Leave comments