A user-centric lens can potentially lead to programs that respond to beneficiaries’ needs throughout the different stages of a program’s lifecycle. MSC has developed a framework that governments, policymakers, and program implementers can use to design and evaluate social protection programs worldwide through a user-centric lens. The framework deploys three overarching principles to design and analyze social protection programs through a user-centric lens. These principles are inclusion, choice, and transparency, which the paper explores in detail.

COVID-19 and FinTechs in Bangladesh—impact and resilience

The COVID-19 pandemic had a pronounced effect on FinTechs in Bangladesh. As an enabling partner and active advocate of the digital financial services (DFS) and FinTech ecosystem of Bangladesh, MSC sought to evaluate the extent of this impact. We conducted this landscape study on FinTechs in 2021 with Visa’s support. We worked with representatives of FinTech, regulators, accelerators, incubators, and the investor community. As a global leader in the payments space, Visa also shared its expertise with MSC. We synthesized insights and sentiment from the local market with global best practices to outline actionable pathways toward building resilience for FinTechs in a post-pandemic world. The phase 2 report evaluates the impact of COVID-19 on FinTechs in Bangladesh and uncovers routes to building resilience.

The report from the first phase study is available on the MSC website

Low awareness of fertilizer subsidy: A challenge to subsidy reforms

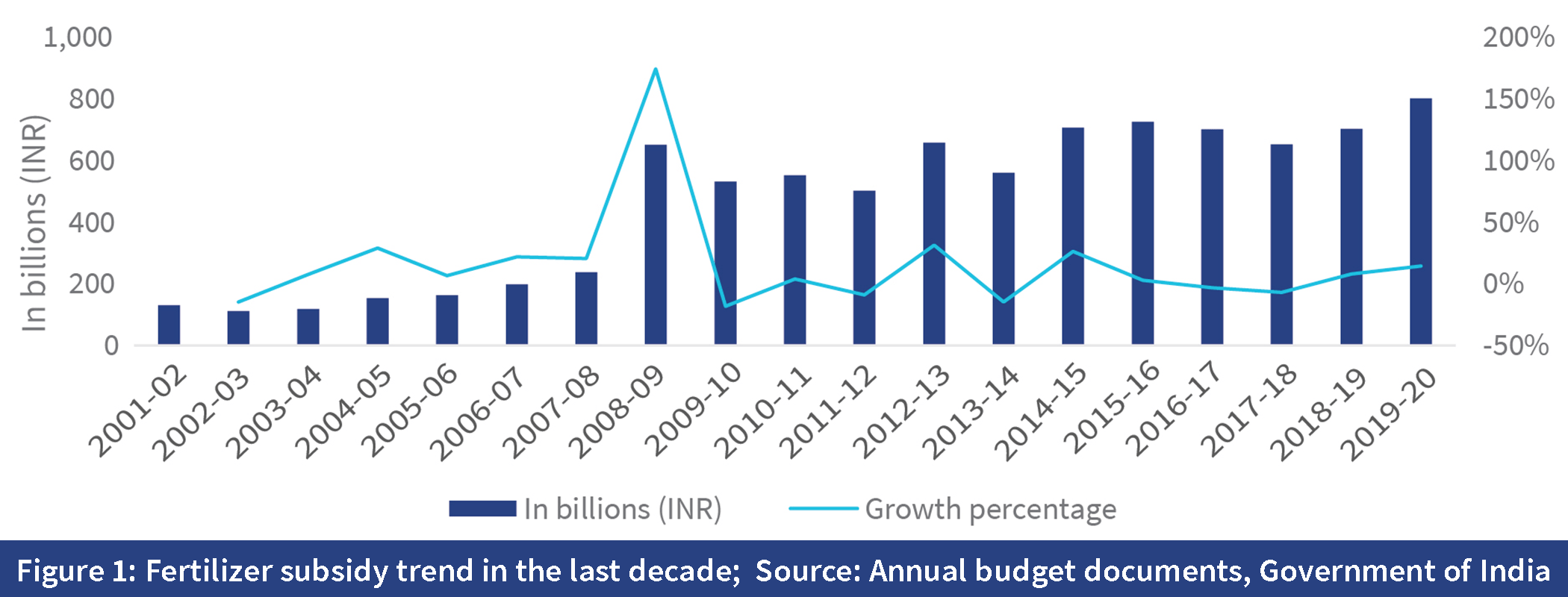

In the past two decades, the Government of India has increased the subsidy provided on fertilizers from USD 1.3 billion to USD 11 billion, as illustrated in the graph below. The subsidy has remained consistent at around 1-1.5% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, over the years, the distribution of fertilizers has become prone to “leakages.” The Economic Survey of 2015-16 estimated that 65% of the fertilizer produced does not reach the intended beneficiaries—small and marginal farmers.

In response, the Government of India (GoI) modified the fertilizer policy in 2018-19. It introduced a new direct benefit transfer (DBT)system in March 2018. Under this system, fertilizer manufacturers receive subsidy payments only after retailers sell the fertilizer to farmers through successful Aadhaar-based biometric authentication. DBT has facilitated the real-time tracking of fertilizer movement, demand estimation, and availability of stock. DBT in fertilizer helped the GoI save USD 1.54 billion during the first year. However, several challenges persist in the distribution of fertilizer in India.

The government has been considering a policy shift to direct cash transfer of the subsidy amount to the bank accounts of farmers rather than fertilizer companies. This move is expected to improve the efficiency of nutrient usage and ensure the delivery of the subsidy directly to end-users. The draft report of a panel under Ramesh Chand, a member of the NITI Aayog, shined a light on the feasibility of the implementation of DBT to farmers. The report also highlighted the criteria to determine the amount of subsidy, periodicity of subsidy transfers, and the mechanism of fund transfer, using data on beneficiaries and their landholdings from the PM-Kisan program. To ensure that the policy shift is implemented smoothly, it is essential to educate beneficiaries on the new system.

Low awareness among farmers may pose a challenge: Evidence from the ground

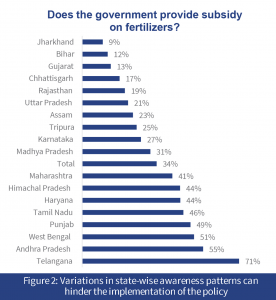

In our study,[1] we assessed the awareness of the subsidy regime among farmers. The data collected from more than 11,000 farmers from 18 states indicated that most beneficiaries are not aware of the current policies and practices. Only one-third of the farmers knew that they purchase fertilizers at a subsidized rate. Another one-third believed that they receive no subsidies on fertilizers, while the rest remained unaware of the subsidy.

In eight out of the 18 states surveyed, less than 25% of farmers knew that the government provided subsidies on fertilizers, (see figure 2).

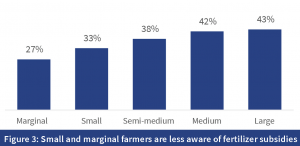

All categories of farmers—marginal, small, semi-medium, medium, and large—had limited awareness of the subsidy. However, the level of awareness varied significantly among the five categories (test statistic 143.96, p-value 0.000).

Of the farmers who were aware of the fertilizer subsidy, around 70% knew that they purchased subsidized bags from retailers, with INR 720 (USD 10) mean subsidy per bag. This amount was close to the subsidy amount provided by the government per bag of urea.

The challenges ahead

Some of the states that consume high amounts of fertilizer, such as Bihar (12%) and Uttar Pradesh (21%) have low levels of awareness regarding subsidies on fertilizer. A policy shift to deliver the subsidy directly into the bank accounts of farmers may evoke shock and displeasure since this would require farmers to first purchase fertilizers at the market price.

When asked about their preference for the subsidy regime, less than half (43%) of the farmers who were aware of subsidy on fertilizers preferred direct transfer into their account to the current option of buying subsidized bags of fertilizers. A possible reason for this reluctance is the high upfront cost involved in the purchase of fertilizers at non-subsidized rates. Farmers may find these costs difficult to bear given the high indebtedness among farming households. Based on our study, we found that farmers may need an additional up-front investment of INR 20,850 (USD 297.86[2]) to purchase fertilizers. According to the All-India Debt and Investment Survey, 2016 of the National Sample Survey Office, the incidence of indebtedness stood at 31.4 % among rural households, with an average debt of INR 110,438 (USD 1,488) and a debt-asset ratio of 7%. More large farmers (69%) and medium farmers (67%) with higher incidences and amounts of debt preferred the current subsidy policy as compared to small (55%) and marginal farmers (52%) (Pearson’s chi-square statistic of 149.52 and p-value = 0.000). Based on their experience with other programs, farmers fear that the subsidy may get delayed or they may not receive the amount altogether due to technical failures. As the purchase of fertilizer at the market rate involves high upfront investment, farmers may be reluctant to change.

Need for a focused communication strategy

The obstacles around a policy shift in subsidy are two-fold. Firstly, with low awareness of the current subsidy regime, farmers may find it difficult to accept the idea of receiving the subsidy amount directly into their bank accounts after purchasing fertilizers at market rates. Secondly, the preference for the current subsidy policy among farmers may prolong the process of implementation if the policy shift is not communicated properly.

Communicating the shift in policy will be key to transitioning from the status quo to the proposed approach. MSC’s experience shows that effective communication before, during, and after reforms in subsidy is essential to ensure its smooth roll-out. An effective communication strategy will need a range of considerations and components for different stakeholders. The government will have to evolve a communication strategy that involves the following elements:

- Use outreach and two-way dialogue with citizens to highlight the need for reforms and their benefits;

- Consult with stakeholders and institutions to understand their concerns and perceptions about the planned reforms;

- Enable a feedback mechanism and an effective grievance resolution mechanism;

- Communicate consistently through evidence-based messages to build understanding and support for reforms, as well as minimize negative perceptions and potential social impacts.

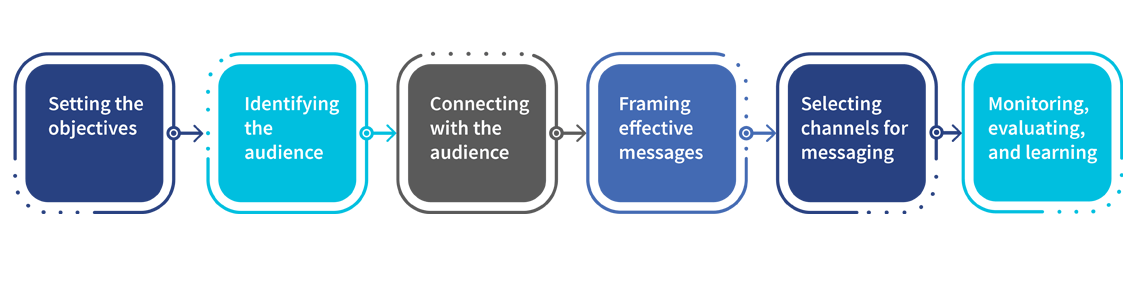

Drawing from our experiences on G2P payments and direct benefit transfers, MSC has devised a communication approach to develop and deliver impactful messages to stakeholders on any policy change. Based on Well Made Strategy’s approach, this six-step process recommends –

Before the government implements a shift in policy, it must consult stakeholders, communicate with them effectively during implementation, and address their concerns.

Before the government implements a shift in policy, it must consult stakeholders, communicate with them effectively during implementation, and address their concerns.

________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] MSC (MicroSave Consulting) undertook a pan-India study in 2018 on the process evaluation of DBT in fertilizer. The research used a nationally representative sample of 11,281 farmers and 1,182 retailers from 54 districts of 18 states. The quantitative research provided national and state-level point estimates on the status of implementation of the pan India roll-out of the Aadhaar-enabled fertilizer distribution system.

[2]The calculation is based on the findings of the process evaluation of the DBT-fertilizer study done in 2018.

Agreement signing with Bank Asia and MSC Global Consulting Pte Limited intending to build resilience and financial health for Post-e-centers Agents in Bangladesh

Mr. Md. Arfan Ali, President and Managing Director of Bank Asia, and Mr. Graham Wright, Group Managing Director of MSC signed the agreement on behalf of respective organizations. The event was also presided by Mr. Ala Uddin Ahmad, CEO of MetLife Bangladesh, and Mr. Krishna Thacker, Asia Director of MetLife Foundation.

Both parties signed the agreement to undertake a project named “Livelihood and income generation for post-e-centers, and building resilience and financial health for LMIs in Bangladesh.” Through this project, MSC intends to work with Bank Asia to build the resilience of agents and improve the financial well-being of users of financial services in Bangladesh.

Bank Asia aims to strengthen the front-end infrastructure of the post e-centers of Bangladesh Post Office, train its agents and staff, and increase the bouquet of services that LMIs need. MSC will help Bank Asia strengthen the infrastructure of postal agents to make them transaction-ready. The overall objective is to build the resilience of the postal agent banking channel to strengthen the financial health of the LMI population in Bangladesh.

In the event, Mr. Md. Arfan Ali said, “Post offices across different parts of the world offer postal banking services, but Bangladesh is far behind. Bank Asia has taken the initiative that the post office in Bangladesh will be the Postal Bank and be connected with international bodies such as the postal association worldwide and bring banking services to doorstep people.” He believes that this memorandum of understanding between MSC, Bank Asia, and MetLife Foundation will make credit facilities easier and give people extra boost-up to the post banking initiative. He hopes that it would create a new horizon by including the marginal people to banking services.

Mr. Graham Wright spoke on behalf of MSC. He noted, “We are excited to use our experience

in other markets and support Bank Asia to strengthen its agent network further. Building on our previous work, MSC seeks to help its agents build resilience, especially since the pandemic. We will help Bank Asia’s customers build better financial well-being.”

Bangladesh has made rapid strides to bring financial access to low and moderate-income (LMI) customers in the past few years. This has increased formal banking accounts from 20% (in 2014) to about 50% (2017) of the adult population. However, the problem of financial access and usage persists in Bangladesh.

This trend is rapidly changing with collaborative efforts from public and private sector providers. With active support from MetLife Foundation, MSC and Bank Asia intends to help millions of people access and use financial services more conveniently with lower opportunity costs.

Bank Asia has already built one of the most significant agent banking networks locally and globally, collaborating with private and public organizations. Under this new business concept, Bank Asia will provide financial services through postal outlets joining hands with the postal department of Bangladesh.

MicroSave Consulting (MSC) is an international financial inclusion consulting firm dedicated to strengthening institutions’ capacity to deliver market-led, scalable financial services to all people. Over the past 20 years, MSC has designed and implemented nearly 75 digital finance projects across Africa, Asia, and Latin America with more than 200 banks, MFIs, and MNOs to develop and test 200+ different financial inclusion products and channels.

MetLife Foundation is committed to expanding opportunities for low- and moderate-income (LMI) people worldwide. The foundation partners with nonprofit organizations and social enterprises to create financial health solutions and build stronger communities while engaging MetLife employee volunteers to help drive impact. Since 1976, MetLife Foundation has contributed nearly USD 1 billion to build stronger communities. Their financial health work has reached more than 17.3 million low- and moderate-income individuals in 42 markets. The foundation also has a strong footprint in Asia. In Bangladesh, it has been supporting efforts to enhance the financial health of LMI people through targeted interventions, especially for women and micro-merchants. MetLife Foundation continues to support the development of financial health in the region through its flagship i3 Program.

A primer on impact bonds

Social sector financing has emerged as a critical need to achieve the SDGs for developing countries like India by 2030. This blog explores why the Indian government should focus on outcomes-based financing instruments like impact bonds to ensure development objectives stay on track. This is particularly important at a time when fiscal challenges are likely to persist and hinder the expansion of existing welfare programs.

SIBs can make development spending more effective

In late 2019, the IFC estimated an annual gap in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) financing worth nearly USD 2.5 trillion in developing countries.[1] According to the OECD, the COVID-19 pandemic increased this shortfall by USD 1.7 trillion in 2020. This amount included a gap of USD 1 trillion in pandemic recovery measures by advanced economies. In June 2021, estimates indicated that India needed USD 2.64 trillion to meet the SDGs by 2030. While fiscal budgets will remain crucial to meet SDGs, the widening financing gaps highlight the case for private capital to support development outcomes.

Results- or outcomes-based financing (RBF or OBF) are an essential mechanism that can help private actors contribute considerably to development goals. Impact bonds are a specific RBF approach that has gained traction over the past decade. They are outcomes-based contracts where private investors provide upfront capital for a development project or service. They are repaid with interest only if the project achieves pre-defined results, evaluated by a third-party assessor. Social impact bonds (SIBs) and development impact bonds (DIBs) shift the focus of development projects from activities and inputs to outcomes. They connect outcome payers,[2] service providers, and private investors to deliver measurable impact within specified timeframes. Impact bonds align risks and social returns and create incentives for all stakeholders, particularly investors, to ensure efficient project execution and rigorous monitoring and evaluation.

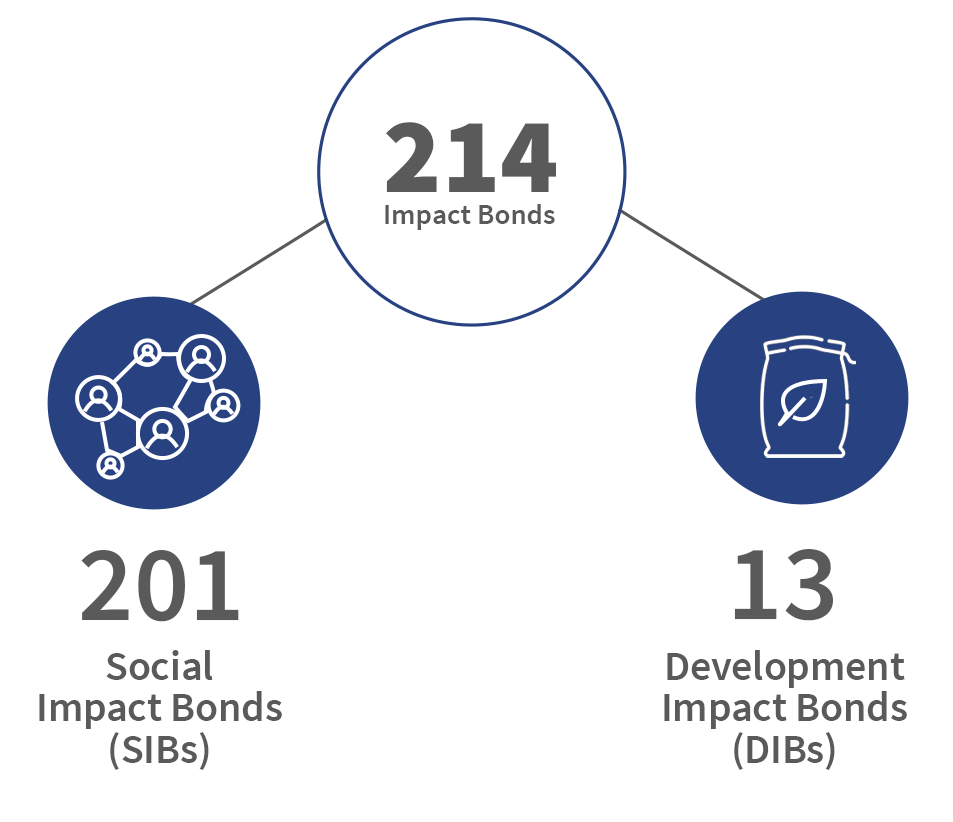

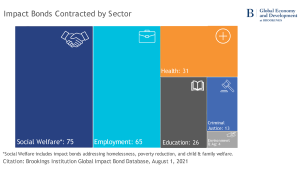

Since the first SIB launched in 2010 and DIB in 2015, investor appetite for these instruments has risen steadily. As of August 2021, 214 impact bonds were contracted in 35 countries across six sectors, with USD 437 million in upfront investments and more than USD 460 million in total committed outcome funding.[3]

Since the first SIB launched in 2010 and DIB in 2015, investor appetite for these instruments has risen steadily. As of August 2021, 214 impact bonds were contracted in 35 countries across six sectors, with USD 437 million in upfront investments and more than USD 460 million in total committed outcome funding.[3]

Impact bonds have been used across various thematic areas—healthcare, education, clean water and sanitation, climate change, and skilling and employment.

The potential role for SIBs in India and the developing world

The potential role for SIBs in India and the developing world

Pandemic-induced public spending has increased fiscal deficits and constrained the short-term development budgets of several countries, such as India. National and sub-national governments can consider using SIBs to overcome this hurdle for specific interventions for which outcomes can be quantified. The arrangement facilitates financial risk-sharing and encourages fiscal prudence as payments are made if outcomes are delivered. Moreover, governments get the necessary lead-time before payouts, as contracts typically last over a reasonable timeframe, often between three to five years. Forecasts depict macroeconomic conditions to stabilizing and improving over that timeframe.

SIB projects differ from traditional government-led ones—they shift the focus of funding from inputs and activities to outcomes. Government-led projects often remain constrained by political prerogatives or rigid procurement and partner selection processes. They tend to be risk-averse at the cost of innovation, unlike SIBs. Hence, government projects generally deliver sub-optimal results in terms of service delivery, meeting budgeted costs and timeframes, and beneficiary targeting. They may fail to address critical needs, such as improving learning outcomes among primary school students or optimizing maternal nutrition. Project failure in such cases sets backs the development impact by years.

SIBs can enable innovation by investing in smaller-scale yet catalytic projects. They provide the initial risk capital to identify successful models that governments can later scale. The multi-stakeholder nature of the approach also facilitates accountability. The interplay between innovation and stakeholder cooperation can help develop new design and development models using a results-based framework. These models can lead to more effective outcomes while assuring double bottom returns for investors.

The Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC) in Maharashtra has taken the lead in SIBs. It signed an MoU with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in December, 2020 to co-create India’s first SIB to deliver quality, affordable, and accessible healthcare. PCMC will cover costs only if pre-defined targets are met, which limits the risk of inefficient and ineffective spending. Governments can also learn from other successful IB-backed programs, such as the Educate Girls Development Impact Bond in Rajasthan that delivered spectacular impact three years after implementation. The program helped students achieve 160% of final learning targets and surpassed the enrollment target at 116%.

Local and state governments need to identify similar projects to scale up that address fundamental development gaps. SIB-backed projects can create a virtuous cycle[4] of investment commitments. The investment will lead to successful outcomes, led by strong data-driven management and rigorous evaluations. The cycle will enhance the abilities of payers and service providers to attract capital. The approach would help public authorities optimize the use of resources and ensure timely delivery of services.

Aligning public-private effort

As of August 2021, developing countries had only 19 contracted impact bonds—12 DIBs and seven SIBs. The scope for growth in this market is considerable. India and many other developing nations already have relatively well-functioning approaches to public-private projects (PPPs) for significant infrastructure needs, such as the development of airports and roads. There are, however, few parallels in the realm of social infrastructures, such as co-developed healthcare facilities or educational institutions. Impact bonds, while not a panacea,[5] can help co-create scalable and catalytic PPPs to meet development aspirations.

Ultimately, the positive impact of utilizing innovative financing instruments like SIBs now could have long-term benefits. Governments must not allow constrained fiscal capacity to compromise welfare delivery. Prioritizing multi-stakeholder projects even if they are more localized can provide valuable lessons for development programming, funding, and implementation going forward.

[1] Doumbia D., Lauridsen M.L., p.2, Note 73, Fresh Ideas about Business in Emerging Markets, EM Compass (October 2019)

[2] SIBs and DIBs are distinguished by the outcome payer. Governments are outcome payers in SIBs while external donors, such as philanthropic organizations, government aid agencies, or multilateral institutions, are the outcome payers in a DIB.

[3] Gustafsson-Wright E. et al.; Social and development impact bonds by the numbers – July 2021 snapshot, Brookings Institution (July 15, 2021)

[4] Bohra L., Impact Bonds: An emerging market opportunity for innovative financing, ET Government (March 18, 2021)

[5] Nouwen C., Lee D. & Hornberger K., Five myths about impact bonds, India Development Review (May 5, 2020)