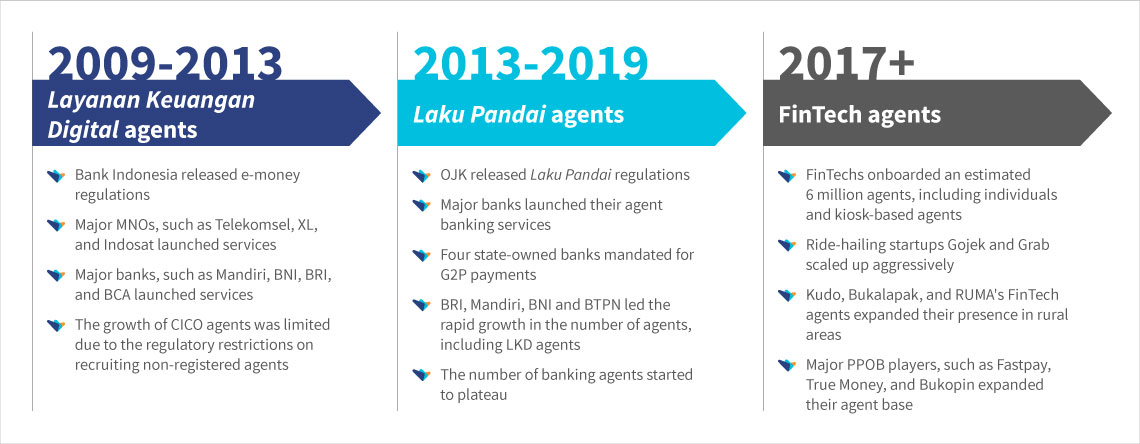

Cash-in and cash-out (CICO) networks are the backbones of any digital financial inclusion program. Despite having one of the largest unbanked populations in the ASEAN region, it was only in 2014 that the Indonesian policymakers passed regulations for branchless banking. The regulations gave impetus to the CICO networks as a last-mile delivery channel for financial access. The country has made remarkable progress on financial inclusion ever since. SNKI’s recent survey shows that financial account access increased from 24% (2015) to 62% (2020) over the past five years. This tremendous growth in financial account access is accompanied by an exponential growth in the CICO networks, both in numbers and services offered.

The graphic below outlines the evolution of CICO agent networks in Indonesia through the years:

Some estimates indicate more than 5 million CICO agents operate in Indonesia, including more than 2 million banking agents (OJK, 2021) and 3–4 million FinTech (non-banks) agents. However, the growth in the absolute number of CICO agents did not affect the quality of access provided through such networks. Further, while the number of CICO agents in Indonesia is considerably high for its size and population, MSC estimates that the actual number of active agents may be significantly less.

In 2017 and 2019, MSC assessed the health and sustainability of CICO networks in Indonesia, which highlighted low benchmark scores for crucial access, usage, and quality parameters. These issues were related mainly to the limited last-mile penetration of CICO networks, low volumes of transactions, and the overall sustainability of such networks as a complementary business line for an agent. The studies also showed that, except for one or two big players with deep branch networks, most service providers struggled to sustain the CICO network, particularly in remote rural locations.

Backed by evidence-based insights, MSC highlighted some of the significant regulatory and policy roadblocks that prevented Indonesian CICO networks from achieving their full potential over the past five years. A critical regulatory issue that slowed the development of quality CICO networks was the lack of professional agent support services. Indonesia did not permit or encourage the concept of experienced third-party agent network managers. Third-party ANMs have been critical to the success of CICO network development in other more mature markets, such as India, Brazil, and Kenya. In January, 2022, OJK announced amendments in the branchless banking regulations. These changes address some of these issues and lay the foundation of an efficient and competitive CICO network infrastructure for the last mile.

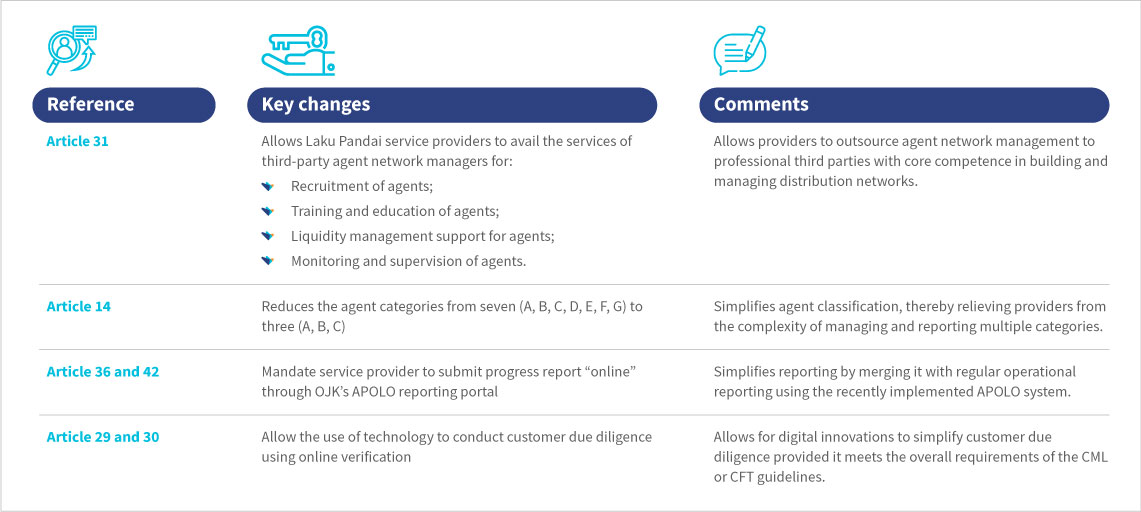

The section below provides significant highlights of the new draft regulations:

Amendments in the draft regulations might appear incremental. Yet, the overall impact of these regulatory changes could be significant when combined with the changes announced by Bank Indonesia for the operations of payment service providers (Bank Indonesia Nomor 23/6/PBI/2021).

MSC published a paper in 2018 on “Aligning regulations to enhance digital financial inclusion in Indonesia.” We highlighted aspects of e-money and branchless banking regulations that required harmonization to reduce entry barriers and create a more level playing field for the service providers engaged in CICO network infrastructure. Bank Indonesia’s latest regulations address some of these concerns by allowing banks or non-banks to recruit individual agents (Article 172) and allowing service providers to collaborate with third parties for agent network management (Article 175).

We expect the recently announced amendments in the regulations to transform the CICO networks in Indonesia. In particular, we anticipate the following critical implications:

Deepening of CICO networks: MSC’s research highlights that in Indonesia, around 85% of bank agents for most service providers operate within a 15-minute distance from a bank branch. Therefore, despite the significant number of CICO agents, many households in remote rural areas lack convenient access to CICO services. The new regulations reduce the entry barrier for service providers to expand their CICO network into remote areas. They can now partner with professional agencies that have the capability and competence to build and manage distribution networks. This model has worked remarkably well in other more mature CICO markets like India, Bangladesh, and Kenya.

Increased competition and consolidation: One or two big players dominate the CICO landscape in Indonesia. Despite the challenging business case, these players either have a brick-and-mortar presence through their existing branch networks in rural areas or have deep pockets to sustain their networks. However, many FinTech players operate on the PPOB (payment point online bank) model and provide a limited set of over-the-counter (OTC) services, primarily top-ups and bill payments. These players may merge or collaborate with large incumbents to sustain such high-volume, low-margin businesses. The new regulations may also increase the choice for customers to access alternative channels for CICO, including a more comprehensive bouquet of digital financial services through non-bank or FinTech agents.

Improvement and innovations in agent management practices: With a booming FinTech ecosystem, Indonesia may also witness the emergence of new FinTech solutions that redefine the existing agent network management practices, including recruitment, training, liquidity management, monitoring, and supervision, and make them more efficient. Given concerns around sustainability, most service providers have not invested adequately in technology-enabled agent network management solutions. Further, due to the regulatory uncertainty, many FinTechs shied away from building agent network management as a standalone business line. MSC highlighted the type of changes that may emerge in a recent report for GSMA, including the use of big data and advanced analytics to monitor agents and track or predict their liquidity positions.

The significant role of agents in customer acquisition: MSC’s ANA research highlighted that only 28% of CICO agents offered account-opening services. This means that most customers transacting at CICO agents were the bank’s existing customers. The Laku Pandai program added only a few new customers. However, the revised regulations may encourage CICO providers to design an efficient digital process that allows customer acquisition for savings accounts and credit. MSC’s research on KYC practices in Indonesia shows that providers can reduce customer acquisition costs significantly through digital identity solutions. However, its success will depend on an enabling digital identity infrastructure provided by the Government of Indonesia.

While the new regulations ease some of the supply-side pain points, the success of CICO networks will continue to depend primarily on critical demand-side issues, such as building appropriate use-cases that drive transaction volumes at the CICO agent point. Meanwhile, questions persist, such as—how will the commercial engagement models between the incumbents and third parties pan out?

The existing regulations maintain the earlier stance of not allowing service providers to price their CICO services over and above the regular transaction pricing in traditional delivery models. Yet, the concerns around sustainability in the existing business delivery model could limit service providers’ ability to adequately reimburse the third parties for their services.

Overall, the new policy direction for the CICO networks looks promising on paper. However, we are yet to see how the industry embraces these recent changes. Are the service providers already fatigued due to sustainability concerns, or do they see the proposed draft amendments as an opportunity to reassess and reframe their CICO strategy?

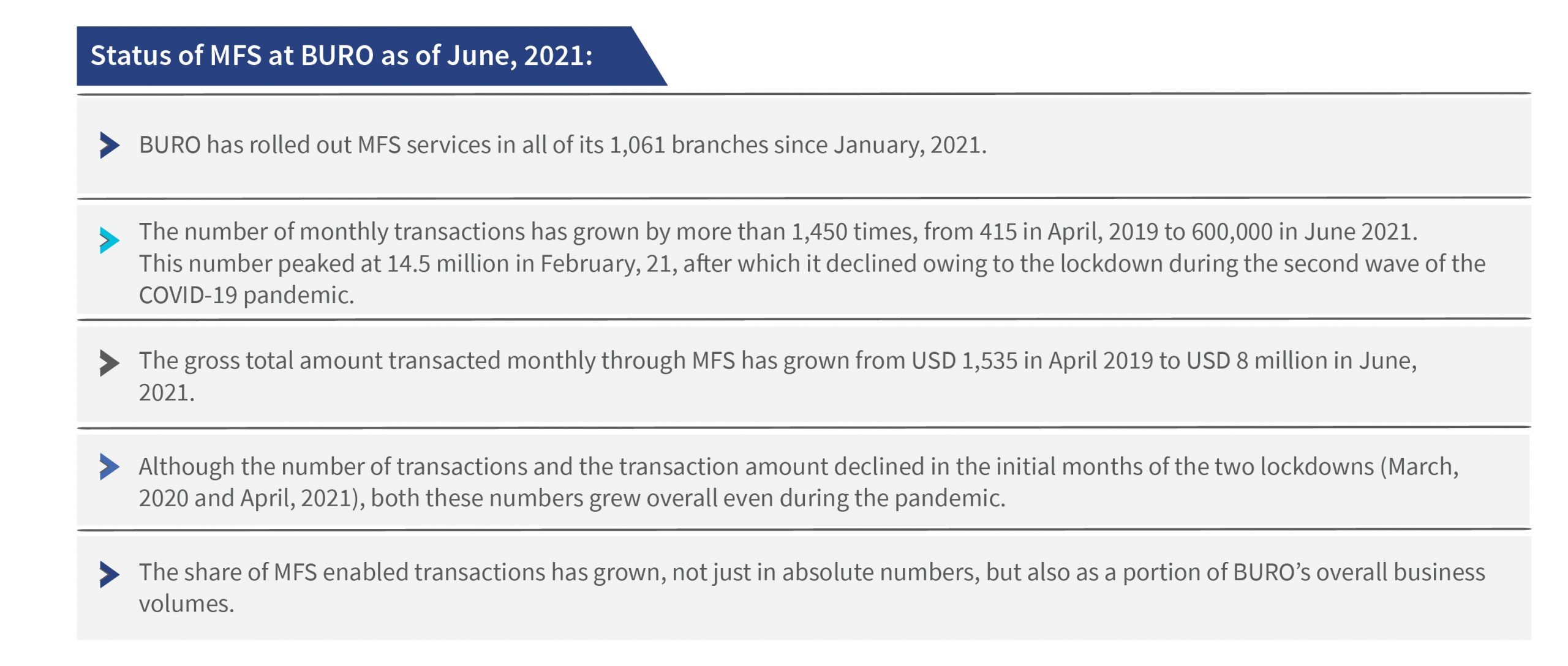

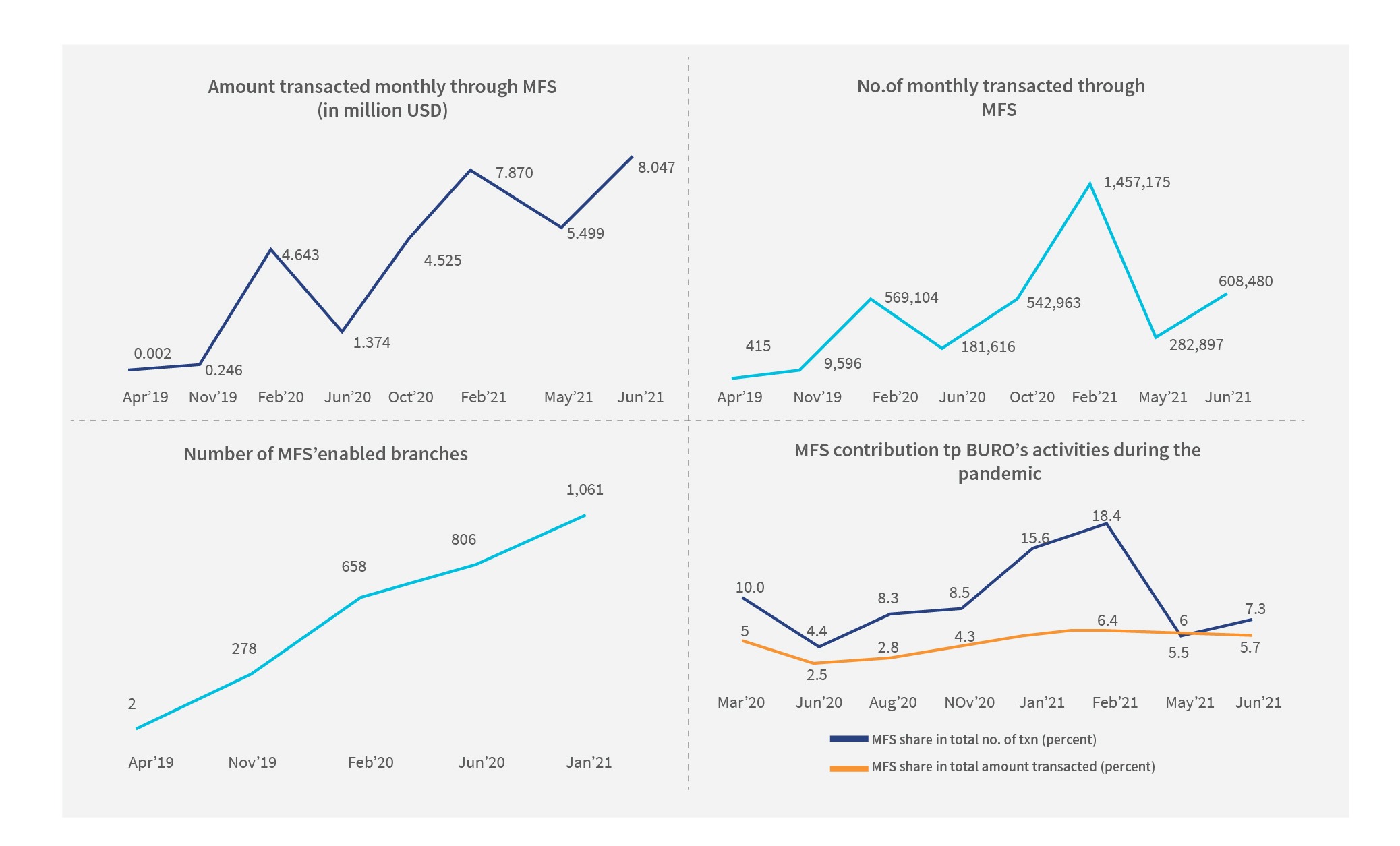

Small shop-owner Ruksana Begum has been a member of BURO for seven years. She used to repay her loans and save in cash at the weekly center meeting. Ruksana had to shut her shop to attend the meeting. So when BURO introduced the option of paying using mobile financial services (MFS), she switched immediately. Ruksana believes that besides saving time, using MFS protected her during the pandemic. Through MFS, she could avoid physical interactions to repay her dues and receive remittances from her husband, who works in Qatar.

Small shop-owner Ruksana Begum has been a member of BURO for seven years. She used to repay her loans and save in cash at the weekly center meeting. Ruksana had to shut her shop to attend the meeting. So when BURO introduced the option of paying using mobile financial services (MFS), she switched immediately. Ruksana believes that besides saving time, using MFS protected her during the pandemic. Through MFS, she could avoid physical interactions to repay her dues and receive remittances from her husband, who works in Qatar.