The Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) program, launched in 2014, has been one of the most critical steps undertaken by the government of India to improve financial inclusion in the country. The program’s mission requires all banks to offer basic savings deposit accounts, helping to ensure basic financial inclusion for all—including women. To date, PMJDY has proven to be a game-changer, not only in terms of financially including a higher proportion of the population, but also in terms of reducing the gender gap in account ownership. As of April 13, 2022, 451 million PMJDY accounts have been opened, of which 55.6% belong to women. According to data from FINDEX, 76.6% of women in India were financially included in 2017, with the gender gap in account ownership dropping to 6% – down from 20% in 2014. And this momentum has extended to rural regions of the country, with an estimated 80.7% of women owning bank accounts in 2021 – compared to 88.1% of men.

However, despite this progress, India’s campaign to boost women’s financial inclusion still faces considerable challenges. Though we currently have no public data that shows the proportion of inactive women PMJDY accounts, we know from the FINDEX 2017 data that 54% of women account holders reported not using their account in the past year, as opposed to 43% of male account holders. Hence, there is not only a substantial gender gap in account ownership but also in account usage.

PMJDY’s blanket approach to financial inclusion has contributed to these gaps. The mission’s mandate is to bring India’s entire population under the ambit of the country’s banking infrastructure – a goal that’s easier to accomplish when the target group is homogenous. But in India, as in other nations, the target group for financial inclusion is characterized by several variations, including not only gender, but also other factors like age, education level and the rural-urban divide. Unfortunately, PMJDY has not taken these differences into account. For example, it hasn’t focused on communicating the need for women to have individual accounts, despite overarching gender norms in India that suppress women’s individuality. It also has not specifically identified measures to make access points more gender-sensitive, which is a critical part of ensuring that first-time female users develop confidence in using formal banking and become regular users. The gender outcomes achieved through PMJDY – both the overall growth in inclusion and the persistent gaps in enrollment and usage– are a consequence of its tendency to overlook women’s unique needs while targeting the entire population at large.

For providers to ensure balanced gender outcomes in any social development intervention, a more equitable approach is essential. As India pursues its National Strategy for Financial Inclusion 2019-2024, it must work to make financial services available, accessible and affordable to all its citizens, both safely and transparently, and to support inclusive and resilient growth. To achieve this, the country will need to work proactively to bridge the gender gap in financial inclusion – not only in terms of account access and ownership, but also in terms of actual use. Below, we’ll explore four things India can do to better enhance the financial inclusion of women.

1. Develop a National Gender Action Plan

In the past decade, approximately 90% of India’s expenditure on gender responsive budgeting has been limited to four ministries—Rural Development, Education, Health, and Women and Child Development. Within these four ministries, some efforts are made to recognize the unique needs of women and design programs specifically to meet them. But for ministries focused on other sectors or themes, the government has adopted a blanket approach to gender, which translates into more general mandates and target-setting at the last mile. Programs focused on these other sectors do not identify gender-specific targets or approaches – and this is mostly the case when it comes to financial inclusion initiatives launched by the Ministry of Finance.

To better address the needs of India’s women, stakeholders must first identify development areas that need gender-specific targets, then create dedicated budgets to meet those targets. To do this, India would benefit greatly from a national gender action plan. The plan should define short, medium and long-term strategies and goals to support women’s economic empowerment, and should include distinct categories of women, such as single women, women below a certain income level, and women of different ages. Such a plan could include gender mainstreaming – i.e., the integration of a gender perspective into the preparation, design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies, regulatory measures and spending programs, with a view to promoting equality across genders and combating discrimination. This gender mainstreaming could be implemented across all layers of administration, including the central, state and district levels, and could mandate the gender-sensitive design of programs to enable equitable outcomes for both women and men. For financial inclusion, this national gender action plan should create mandates for the banking infrastructure to bridge gender gaps. However, these actions should go beyond surface-level approaches like “pink” credit cards marketed to women, focusing instead on priority sector lending, in which a certain proportion of financial institutions’ lending portfolios must be dedicated to women customers, and on mitigating the systemic barriers that women face as they engage with the banking system.

2. Put data to optimal use for women

After China, India is home to the world’s largest population of unbanked individuals (190 million out of the total 1.7 billion in 2017), and women constitute nearly 60% of these unbanked adults, per FINDEX data. One key driver of financial exclusion in the country is the difficulty faced by both the government and the banking infrastructure when it comes to identifying unbanked individuals. If institutions don’t have information on who is unbanked, how will they target them for financial services?

We believe the adoption of gender-disaggregated data across all government programs, combined with data reporting across all administrative levels and stakeholders, will be a game-changer for India and its women. Through this data, program administrators will be able to understand the extent to which women are excluded and neglected systemically, and hence, they will be able to develop more informed strategies to reduce this disparity at both the levels of gender and geography.

For example, the platform the government currently uses to track the status of enrollments for PMJDY at the district level is the Champions of Change portal, part of the Aspirational District Programme anchored at NITI Aayog, the apex public policy think tank of the Indian government. This portal shows the number of individuals with PMJDY accounts per 100,000 people. Since these numbers aren’t gender-disaggregated, there is no visible gender gap in these statistics, and the program’s district-level activities never specifically target excluded women customers, as illustrated by MSC’s experience providing NITI Aayog with strategic and tactical support to enhance financial inclusion in 27 Aspirational Districts (July 2018 to March 2021). If the existing gender gaps were known by a district’s administration and bankers, these stakeholders would know which geographies or clusters of villages to focus on. More data could also help stakeholders organize financial literacy camps and enrollment drives that target excluded segments.

More specifically, India lacks a comprehensive database that tracks the status of financial inclusion and social security at the individual level. Consequently, since multiple financial service providers can cater to the same individual, duplications often occur in the enrollment (in basic accounts and insurance) of specific segments of the population, while excluding vast segments that are vulnerable and hard to reach. Since this duplication is not tracked, trying to gauge a population’s level of inclusion based on a single overall indicator becomes difficult.

A more forward-looking approach would be for the government to introduce a national-level social registry that allows program administrators to identify the unbanked and excluded from multiple selected programs at an individual level, thereby reducing the extent of exclusion. This database would apply to the government’s entire development agenda as if it were a single project, and multiple ministries and departments could use its data to identify targets for their respective mandates. This database would not only solve the problem of the gender gap in PMJDY and other government programs, but also of exclusion across communities and the duplication of enrollment in these programs. Of course, the execution of this idea would require clear mandates, passion, grit and ample resource allocation.

3. Change stakeholder behavior toward women’s access to financial services and their use

Significant behavioral biases push women to more conventionally “feminine” roles in their households and the broader economy, restricting their confidence in managing finances and their participation in jobs and business ventures. This was one of the factors that led to a drop in women’s participation in India’s labor force from 30.3% in 1990 to 18.603% in 2020 (according to World Bank data). We must change these detrimental social norms.

To that end, India has had significant success with its “Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao” (save the girl child, educate the girl child) mission, which intends to change the bias among families against having female children, educating them, or both. Owing to this mission, in 2020, the overall enrollment ratio of girls across all levels of education was reported to be higher than that of boys. A similar behaviorally informed campaign is needed to reconfigure gender norms that limit women’s ability to use a bank account, manage finances and work at par with men in other roles. The campaign could work to show the inherent biases that agents, bankers and family members have, concerning women and men’s behavior around financial services.

4. Redefine financial inclusion success to include usage, leading to improved financial health

The success of financial inclusion efforts needs to be measured in terms of both access and usage. Access is defined as having access to financial services—i.e., having a bank account. Usage, however, needs to be better defined and measured. This could involve identifying and tracking suitable service-level measures and user-experience-related statistics. For example, across the 27 Aspirational Districts where MSC and NITI Aayog operate, several districts have pockets of villages that remain unbanked due to a lack of telecom connectivity. For women in these pockets at the last mile who have limited agency and restricted mobility, the possibility of obtaining access to financial services, understanding them effectively and using them is practically nonexistent.

Tracking the usage of financial services by women and men will ultimately drive women’s financial inclusion. In the absence of such statistics, the real story of women’s financial inclusion cannot emerge, as MSC’s studies indicate that instances of men operating financial products and services as proxy users on behalf of women (in order to exercise control over their financial lives) are rampant. Tracking the usage of financial services by women will help inform deep-dives into the data that can identify other critical issues that impede their adoption of these services. These may include ineffective channels and mediums of financial education, as well as irrelevant or non-intuitive user interface/user experience design among digital financial services.

Will the above measures be sufficient to help ensure the financial inclusion of all women in India?

The quick answer is, perhaps, no. But these measures can be a good start. India has been at the forefront of digital innovations in financial services, helping millions participate in the financial economy through their mobile phones. However, this progress and innovation are meaningless for the millions of Indian women who remain excluded from basic banking in the first place. The strategies we’ve discussed here have a direct impact on women’s financial inclusion. Ultimately, once these women are in the ambit of financial services, policymakers may want to adopt a broader framework, such as the Alliance for Financial Inclusion’s GRID, to enhance the use of digital financial services by the women who need them most. But in the meantime, India must do more to make the promise of its financial inclusion efforts into a reality for the millions of women who have been left behind.

The Next Billion first published this article on 27th April, 2022.

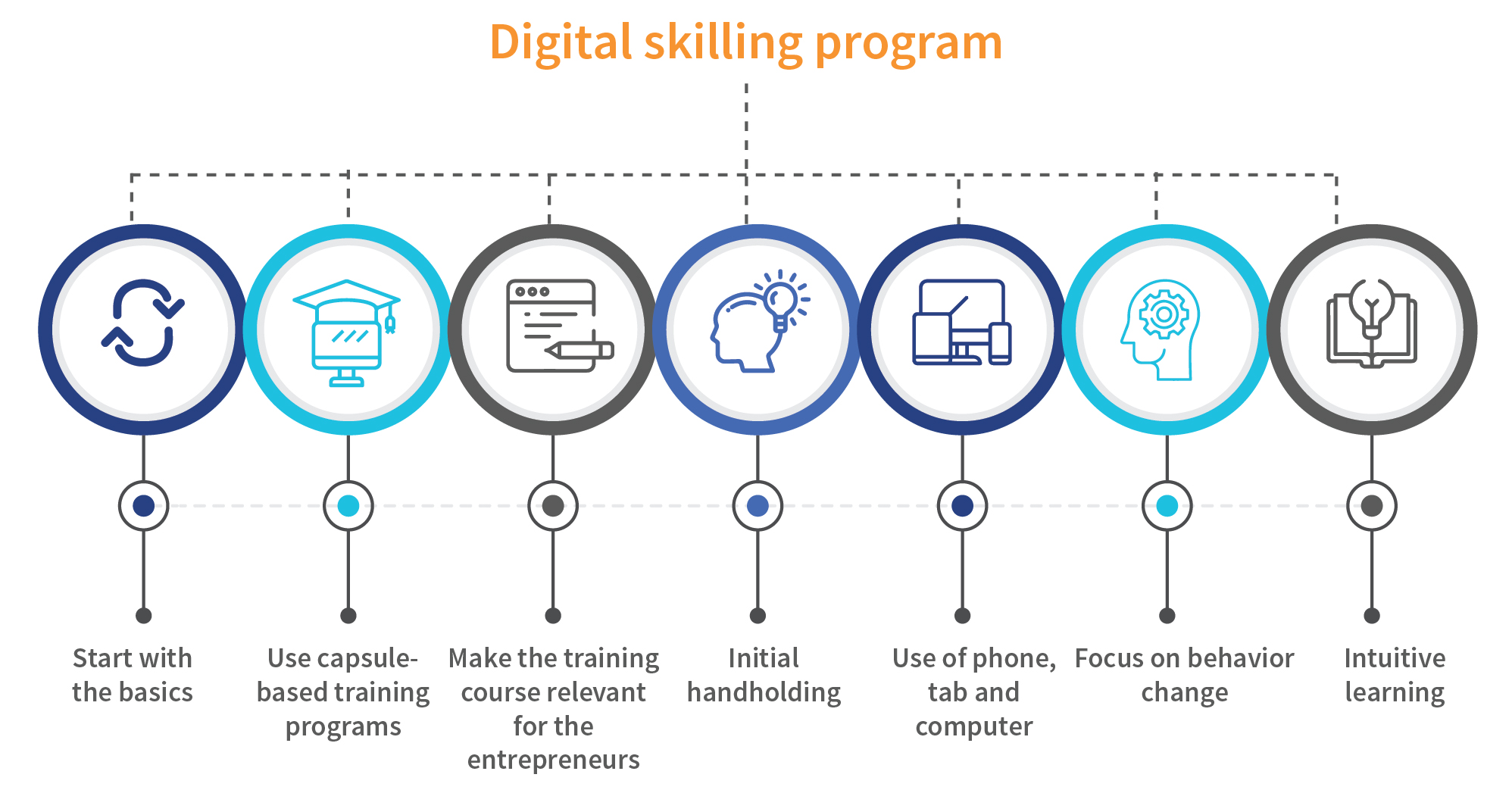

Figure 2 showing different elements that can make digital skills training effective

Figure 2 showing different elements that can make digital skills training effective