“No one can withdraw money without my consent after I receive stipends directly in my account. The stipends also help me save for my child’s educational needs, as we would earlier spend any cash doles mostly on household expenses,” says Rabia, a beneficiary of Bangladesh’s Primary Education Stipends Program (PESP).

Nearly all women we spoke to in Bangladesh prefer digital transfers over cash. To them, digital transfers translate to more direct control over their stipends.

Substantial evidence shows digitized G2P programs improve access to financial products and services and enable their use while streamlining the delivery of social security benefits. Digitized G2P programs are associated with positive effects for both the programs’ governments and beneficiaries. However, experts often debate if it is better to deliver benefits to women in programs that target the household or children.

Impact evaluations of gender-centric conditional cash transfers have looked at drivers of gender outcomes, such as monetary control and bargaining power in household decisions. The Primary Education Stipends Program (PESP) in Bangladesh directs the benefit to women through mobile money. PESP intends to increase the enrolment, attendance, and retention of children in primary schools. The program distributes quarterly G2P benefit of USD 1.6 (BDT 150) per beneficiary with an upper limit of USD 5.23 (BDT 500) per family to the mothers of children enrolled under the program.

BMGF’s D3 (Digitize, Direct, and Design) framework highlights that digitized G2P programs directed at women have a more transformative impact on them. Such targeted programs can help them make better decisions, include them financially, and lead them to adopt digital behavior. This blog uses the D3 framework to review PESP’s impact in Bangladesh on gender empowerment and reviews findings from an assessment of PESP conducted by MicroSave Consulting (MSC) and the Centre for Global Development (CGD).

The digitization of PESP

Since 2013, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) has made active progress in digitizing several social security net programs (SSNPs). With the rapid rise of mobile financial services, policymakers saw merit in distributing G2P benefits digitally to reduce costs and introduce transparency in program administration. In 2016, the PESP was shifted from cash to mobile money. This shift was crucial to ensure the financial inclusion of women, especially those from rural areas.

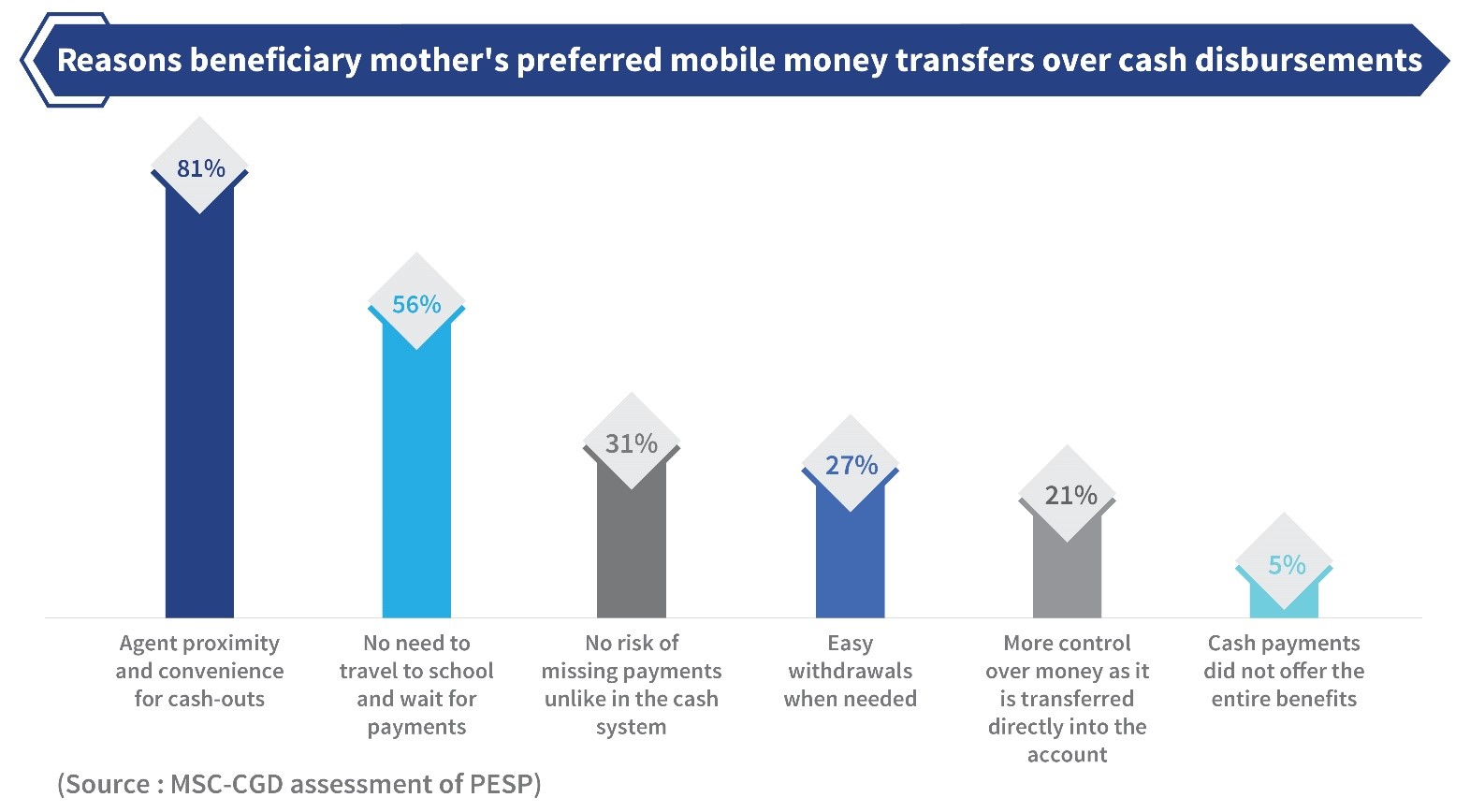

The digitization of PESP led many women (79%) to open mobile money accounts for the first time. In MSC’s assessment, 93% of mothers who experienced both cash and mobile money transfers reported a clear preference for digital stipends.

Mothers appreciated mobile money transfers for their convenience and low-cost access, and in cash-out. In contrast, with the cash disbursement system, they incurred high opportunity costs in travel and time needed to visit schools to collect the payment.

The digitization of PESP stipends also led to an increased usage of financial services. 46% of respondents mentioned using their mobile money accounts beyond PESP cash-outs. These women used their accounts for funds transfers (96%), savings (68%), and value-added services such as bill payments and mobile bill top-ups (17%).

Directing the benefits to women

Besides ease of access and convenience, mothers also preferred mobile money for better monetary control over the quarterly stipend benefits. A recent mandate from mobile money providers requires the beneficiary mothers’ national identity cards (NID) to be linked with their SIM. Before this requirement, several women did not own mobile phones and gave their husbands mobile numbers when they enrolled with PESP. In fact, a recent study by GSMA (2021) indicated that only 64% of women in the country have access to mobile internet as opposed to 84% of men. The mandate ensured that the stipend benefits reached the sole intended female beneficiary of the program and family members did not divert the funds into non-educational outcomes.

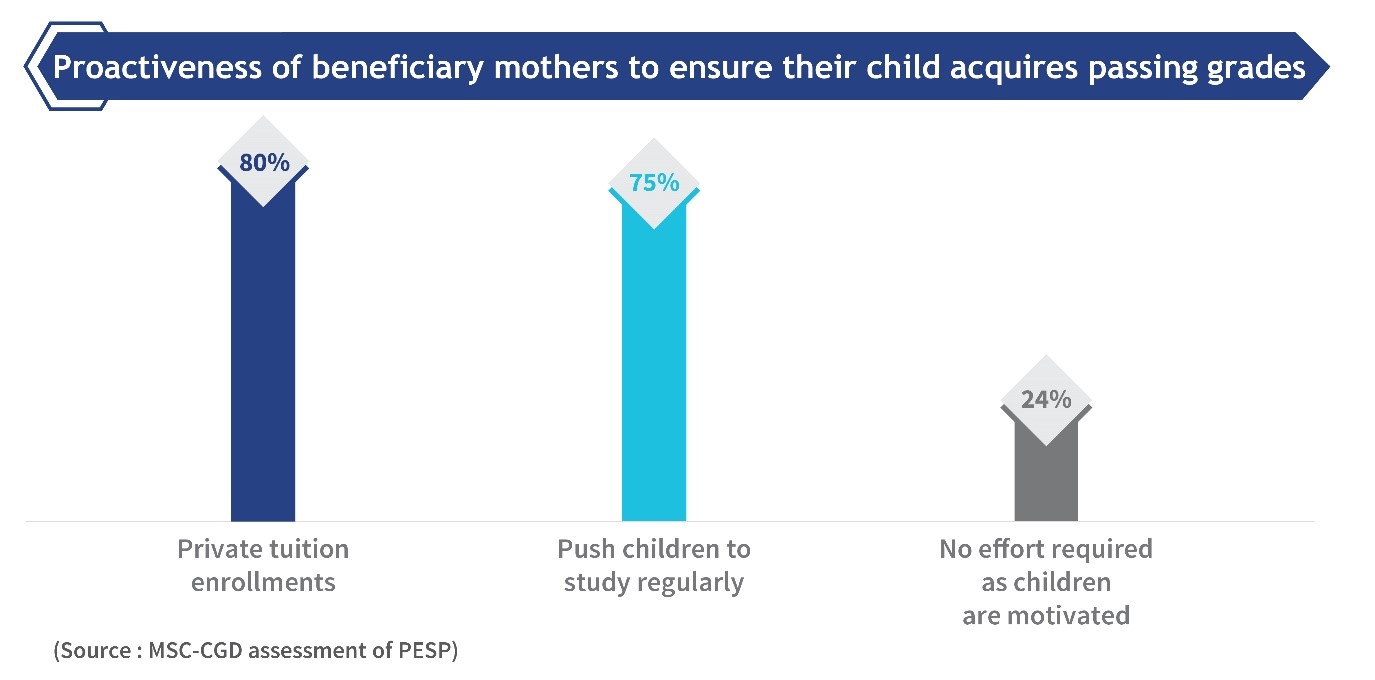

Evidence from the MSC-CGD assessment indicates a strong positive relationship between mothers who use their own mobile wallet accounts for PESP benefits and their economic decision-making agency. Several mothers use PESP stipends to buy school supplies (stationary and school uniforms) and private tuition after school hours. Digital stipends also help mothers save a portion of the payment for future education needs. The households of marginalized PESP beneficiaries are highly susceptible to income shocks. Therefore, the savings help prevent disruptions in primary education.

The disbursal of PESP benefits mandates the students to maintain a minimum grade and attendance. Hence, women push their children to study to receive the stipends. Such efforts also mean that mothers prioritize the quality of learning outcomes.

Directing the benefits to women has significantly increased their control over the stipends. 74% of respondents who received PESP mentioned that they have more control over digital stipends than cash disbursement. 92% of respondents who received PESP mentioned that they have more control over the stipends because no one can withdraw them without their consent.

However, since digital benefits are being transferred directly to women, many women express the need for more knowledge and skills to transact digitally. Anecdotal evidence suggests that as nascent mobile money users, women with feature phones need agent assistance and hesitate to navigate digital banking channels independently.

Designing the program to expand opportunities for women

Before 2019, school-level committees were formed to target mothers eligible for PESP. Other targeting mechanisms, such as categorical and means testing, were deployed with mandatory rural coverage of 60%. In 2020, policymakers in Bangladesh took yet another stride to introduce greater transparency and accountability in the program by universalizing PESP coverage. Through this step, policymakers intended to reduce the role of politics in beneficiary selection and expand geographical coverage to include several poor urban children.

The expansion of program coverage also amplified ripple effects on women’s economic and digital inclusion. PESP provided predictable income streams through the quarterly PESP stipends. The program was made shock-responsive during COVID-19. The stipends were increased from USD 1.05 (BDT 100) to USD 1.6 (BDT 150) per child, with a cap of USD 5.23 (BDT 500) per family. Two children from the same family receive USD 3.14 (BDT 300) each, three from the same family receive USD 4.18 (BDT 400) each, and four from the same family receive USD 5.23 (BDT 500 each).

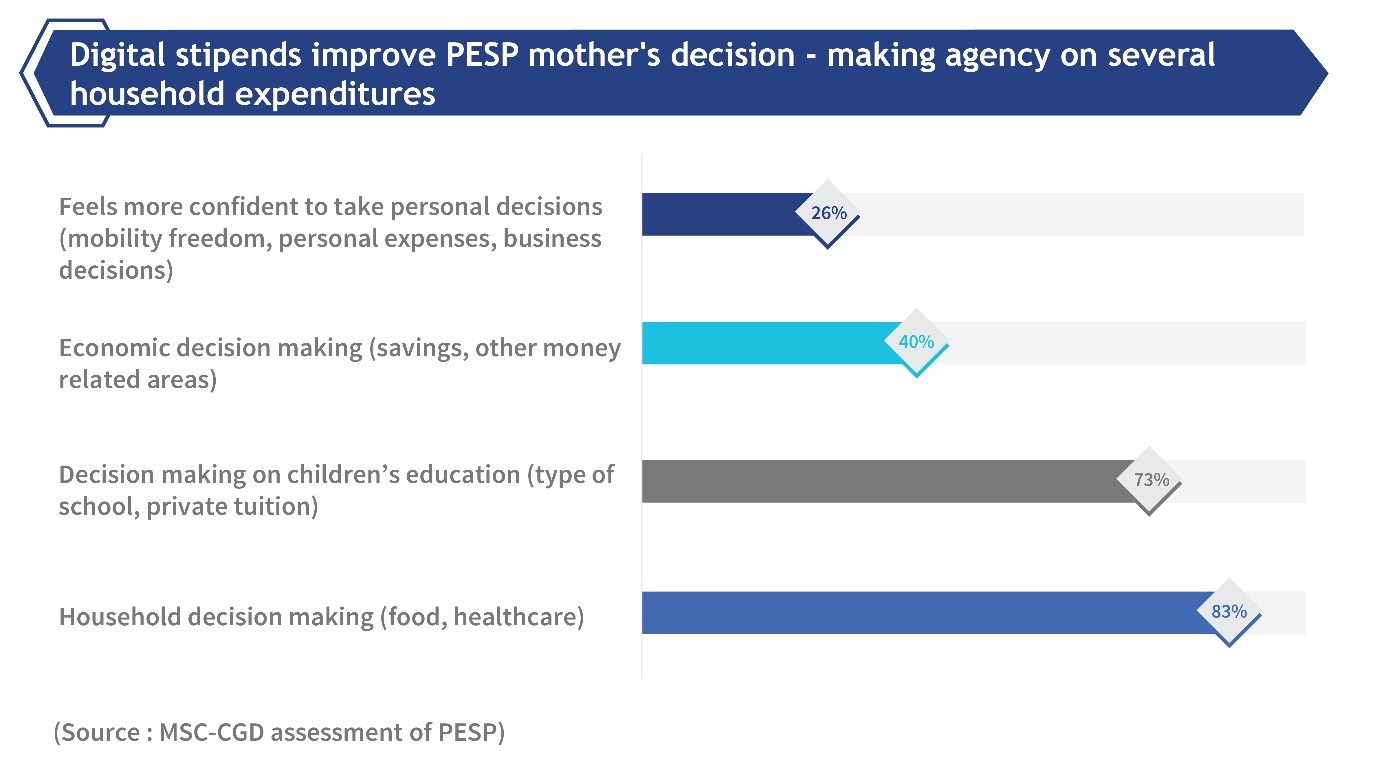

Deciding stipend use and timing of cash-out helped women hone their financial decision-making skills. They started to increase their bargaining power in household decision-making related to savings, investments, and health. Despite 90% of women continuing to depend financially on their husbands, 73% of PESP women reported higher participation in several household decisions after their enrolment.

PESP has made a significant difference for low-income women. It has expanded financial inclusion, enhanced control over household decisions, and increased their agency over the stipends. The program has succeeded since digitization and incorporated gender centrality in its design.

In the future, program implementers must take measures to address exclusion errors and ensure timely communication with beneficiary mothers on evolving program conditionalities such as NID-SIM card linkage. The database of 13 million PESP beneficiaries can help policymakers target and enroll women effectively into other gender-centric social protection programs, such as livelihood generation and the provision of health insurance.

During a crisis, policymakers could also use the database to provide women immediate cash transfer benefits. Complementary linkages between gender-centric social protection programs can ensure a more meaningful and long-term impact on gender equity and quality of life for women—allowing them to take control of their financial life and beyond.