COVID-19 had a devastating impact on micro and small enterprises in developing markets, with evidence pointing to women entrepreneurs being the hardest hit. The panel will briefly discuss the challenges female entrepreneurs have faced in the aftermath of COVID-19. We will speak with a female entrepreneur, as well as an organization dedicated to supporting women led startups and businesses to learn about their experiences. Focus will be given to innovative interventions from which women entrepreneurs benefited during and after the pandemic, and lessons learned that have ultimately made female entrepreneurs more resilient.

Webinar series—Inspiration, Insights, and Learning (I2L): Digital transformation: Is the banking and microfinance industry ready?

We organized a discussion with a panel of experts drawn from leading microfinance institutions, banks, regulators, and philanthropic organizations worldwide. Their conversation focused on the following:

- Digital transformation strategy and framework,

- Data privacy and consumer protection in the digital age, and

- The role of regulators in supporting digital transformation.

Click on the timestamps from the webinar stream to hear specific segments.

00:05 – 03:37 Welcome note and introduction by Dr. Ravi Kant (Digital Transformation Emerging Area Group Lead, MSC).

03: 38- 09:56 Presentation on the importance of digital transformation by Anup Singh (MSC Africa – Regional Head).

10:07- 56:03 – A panel discussion: Two rounds of conversations with our panelists, moderated by Juliet Ongwae (Digital Financial Specialist, MSC)

Panelists:

- George Njuguna: Information Technology Director (CIO) Safaricom (Kenya)

- Imran Ahmed: Deputy Executive Director, Shakti Foundation (Bangladesh)

- Akhilesh Singh: Chief Financial Officer, Sonata Finance (India)

- Selim R.F. Hussain: Managing Director & CEO, BRAC Bank Ltd (Bangladesh)

- Tatiana Bet: Head of Business Support Unit, MicroInvest (Moldova)

Round 1

11:41- 15:34 George Njuguna: Safaricom, Information Technology Director (CIO) (Kenya), responds to Question 1: Safaricom and its innovations have been a huge enabler for the FinTech explosion in Kenya. This has led to an entirely new and transformed financial services landscape. What are your thoughts on how the digital infrastructure and future business models will look like?

16:13- 21:02 Imran Ahmed: Shakti Foundation, Deputy Executive Director (Bangladesh), responds to Question 2: Shakti has been on this digital transformation journey with the digitization of your microfinance and SME programs. How have digital initiatives helped Shakti Foundation offer customer-centric savings and credit products for low-income customers?

16:13- 29:36 Akhilesh Singh: Sonata Finance, Chief Financial Officer (India), responds to Question 3: As microfinance institutions digitize, what are some of the biggest roadblocks they face when doing so (in India)?

30:14 – 40: 25 Selim R.F. Hussain: BRAC Bank Ltd, Managing Director & CEO (Bangladesh) responds to Question 4: BRAC Bank has focused on transforming into a digitally-led organization, and the numbers show your tremendous success in this journey. How did you manage and execute a culture shift for digital transformation on a large scale (more than 700 agent banking outlets, almost 200 branches, and 300+ ATMs, per its 2021 annual report)?

41:00 -43: 11 Tatiana Bet: MicroInvest, Head of Business Support Unit (Moldova) responds to question 5: As an NBFI focused on lending to MSMEs, what has been your journey in transformation of credit risk management, specifically with credit scoring? What are some of the key lessons learned?

Round 2: Panelists answer the question: What is the biggest myth about digital transformation? Could you please debunk these myths for us?

44:37 – 46:11 George Njuguna: Safaricom, Information Technology Director (CIO) (Kenya), responds to this question.

46:15 – 49:37 Imran Ahmed: Shakti Foundation, Deputy Executive Director (Bangladesh), responds to this question.

49:59 -: 53:57 Selim R.F. Hussain: BRAC Bank Ltd, Managing Director & CEO (Bangladesh), responds to this question.

54:07 – 54:48 Tatiana Bet: MicroInvest, Head of Business Support Unit (Moldova), responds to this question.

56:04 – 58:43 Anup Singh (MSC Africa – Regional Head) MSC presents the concluding remarks.

BRAC Bank experiments with agent banking—a lesson for progressive banks across the globe

This case study on BRAC Bank shares lessons from its journey and its experiments with agent banking. It highlights its unique initiatives in making the agent banking channel a profit-making proposition. By reading the case study, you will get more insights into the key differentiating factors of BRAC Bank’s agent banking for its agents and customers.

The evolution of payments in India—looking ahead

The previous blog discussed the state of India’s digital payments ecosystem. This blog looks at where and how it may evolve further.

NPCI

The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) is the backbone of the country’s retail payments and settlement systems. NPCI’s efforts to build an open source and safe digital ecosystem have transformed how digital payment solutions reach the masses. NPCI now boasts an extensive product suite comprising UPI, AePS, BAP, Bharat QR, BBPS, RuPay, CTS, NACH, IMPS, NEFT, and eRUPI. NPCI will continue to play a pivotal role in enabling India’s 1.2 billion mobile phone users to adopt and access digital payments.

These products are replete with innovation, promote inclusiveness, and create a seamless payments experience for individuals, businesses, and governments. NPCI’s role in pushing India toward a digital economy remains critical. NPCI should address the country’s growing needs through stronger partnerships, besides new relationships with FinTechs, payment service providers, regulators, banks, and other institutions. Concerted efforts are now required from service providers to augment digital payment solutions by developing tailored use cases for each customer segment in the country.

New Umbrella Entity (NUE)

The exponential increase in smartphone users, coupled with the widespread adoption of new-age digital payment solutions, such as UPI, has positioned India as one of the fastest-growing digital payment economies worldwide. The acceleration toward digital payments has come about quicker than planned during the pandemic. PWC and the Payments Council of India (PCI) expect India to contribute ~2.2% of the global digital payment market by 2023. By 2025, digital transactions in India are expected to rise to 167 billion in volume and INR 238 trillion (~USD 3.21 trillion) in value. It presents substantial business opportunities for existing and new players in the digital space.

The New Umbrella Entity (NUE) could bring about greater financial stability and efficiency in the backend system, which NPCI currently manages single-handedly. Key players and allies in the payments ecosystem, such as HDFC, Paytm, PayU, Visa, Punjab National Bank, Union Bank, Google, Amazon, Flipkart, and Tata, have applied to obtain the license for NUE. These entities should make the payments ecosystem more competitive, add to the existing product suites, and bring tailored use cases. These entities will also add to the overall innovation, insights around customer needs, and spending patterns, enabling them to align their offerings to increase the overall financial inclusion for several customer segments.

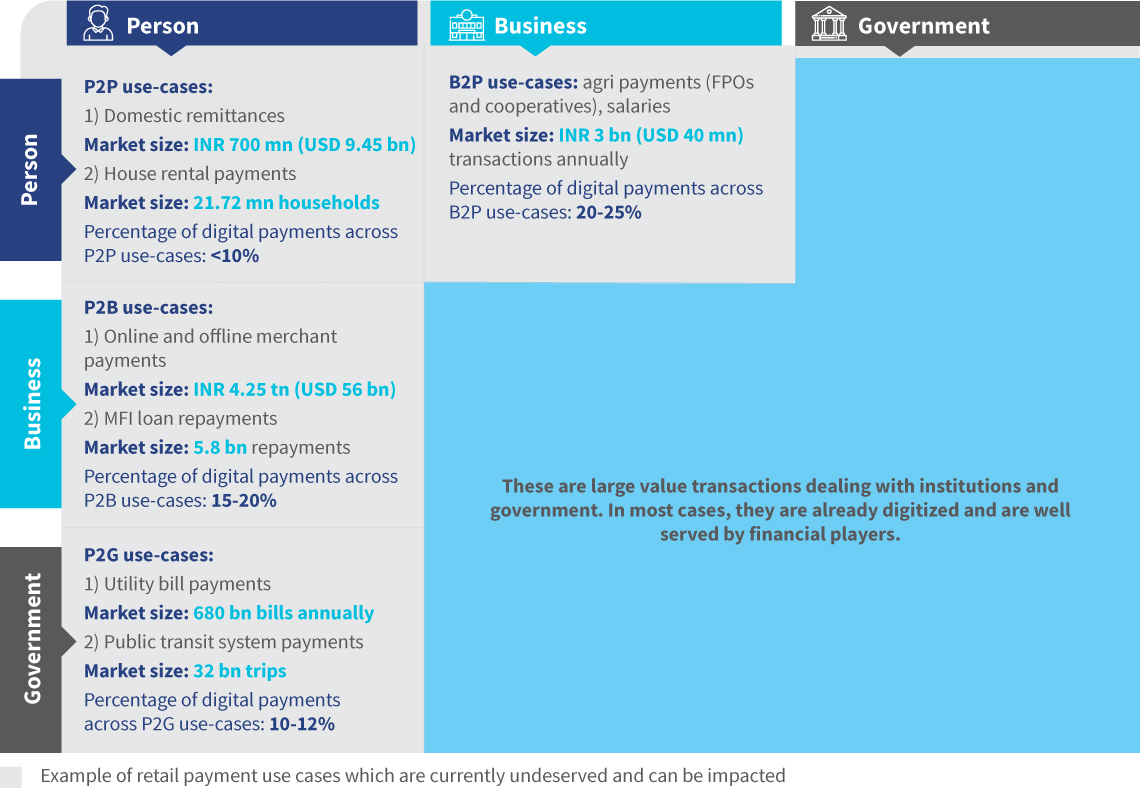

Payments channels

Four payments channels have tremendous potential to be digitized—P2B, P2G, P2P, and B2P. Targeted interventions through digital payment solutions across these channels will help address the specific financial needs of the unserved and underserved LMI customer segments. Promising examples include digitalizing domestic remittances, house rental payments, cash on delivery (CoD) payments in e-commerce, offline merchant payments, repayment of microfinance loans, recurring payments in agriculture and allied value chains, utility bill payments, and transactions in the public transit system.

The performance of these payment channels shows potential for growth:

- Migrant workers comprise the largest user segment of remittance services in India. About 120 million migrant workers from rural areas account for 80% of the country’s domestic remittances valued at ~INR 700 billion (~USD 9.45 billion). Presently, around 60% of domestic remittance transactions occur through non-traditional channels, such as friends, family, and agents for remittances. This untapped market offers an opportunity to digitize remittance transactions worth more than INR 400 billion (~USD 5.4 billion).

- India has 63 million micro-merchants in the country who facilitate P2B transactions. Many live in rural areas. While financial service providers have acquired around 10 million merchants, most are more prominent merchants from urban areas. Approximately 90% of micro-merchants currently transact exclusively in cash. The dependence on cash creates a massive potential to digitize cash-based transactions worth INR 4,200 billion (~USD 56 billion), as per MSC’s analysis based on IBEF estimates.

- India’s e-commerce sector is currently worth INR 2,600 billion (~USD 35.1 billion), a value that is forecasted to grow at a CAGR of 27%. Presently, around 17% of India’s total e-commerce transactions occur through cash-on-delivery (COD) payments. Converting even a conservative 10% of these cash transactions to digital presents an opportunity for digitizing transactions worth ~INR 45 billion (~USD 0.61 billion).

- India has 202 microfinance institutions (MFIs) with a branch network of 19,073 and 152,000 employees, per the Bharat Microfinance Report 2020. These MFIs have more than 59 million clients, primarily women, and an outstanding loan portfolio of ~INR 2,600 billion (~USD 34.6 billion). MSC’s analysis suggests that more than 95% of these loan repayments happen in cash through MFI field agents, highlighting the potential to digitize 5.8 billion transactions annually. Digitizing these MFI transactions can serve as anchor use-cases for women borrowers and increase the uptake and usage of digital payments across women in India.

- Salaries comprise the most significant use-case of payments made through the B2P channel but most of these payments are already digitized.

- Individual contract payments or payments for agriculture input and allied sectors constitute the next big use case under the B2P channel. MSC’s analysis suggests that transactions worth INR 880 million (~USD 40 million) flow through this channel annually, of which only 20% have been digitized thus far. This gap highlights the massive opportunity to digitize B2P payments.

- MSC’s analysis highlights that the P2G channel sees transactions worth ~INR 36,000 billion (~USD 486 billion). These include payments for government services, donations, bills, and taxes. However, more than 80% of these transactions occur in cash due to the consumers’ limited awareness and capability regarding digital payments and the institutions’ complex legacy systems.

Iris authentication payments

Currently, one in every three AePS transactions fails, with around 17% due to biometric mismatch using fingerprint authentication mode. The high failure rates in AePS transactions through fingerprint-based authentication have created a need for alternate authentication modes. Iris-based authentication provides a better alternative to fingerprint authentication. The iris-based mode is safe and secure—since the iris is difficult to forge, hygienic—as it is a contactless solution, and convenient—since it involves fewer scanning attempts than fingerprints. It is also far more accurate, with a false rejection rate (FRR) of 0.1-0.2% compared to 2-3% for fingerprint authentication.

Around 200,000 iris devices have already been installed across India to manage beneficiary authentication for various government schemes—public distribution systems, pension distribution, and mid-day meals. Currently, five banks—ICICI Bank, Andhra Bank, Fino Payments Bank, Central Bank of India, and RBL Bank are adopting iris-based authentication for AePS transactions. The average cost of an iris device is around INR 3,500 (~USD 47) compared to ~INR 2,000 (~USD 27) for a fingerprint device. Despite the comparatively higher device cost, iris devices have seen good adoption as 9% of Indians use them compared to the global average of 3%.

Way forward

The country’s payments ecosystem has many opportunities to grow and improve. NPCI has made moves to seize many of these opportunities. Meanwhile, the NUEs will encourage and enable innovation and diversification, which should further expand the frontier for digital payments.

That said, concerns about approaches to include those without access to smartphones persist. Regulators can address these concerns by enabling improved and intuitive USSD-based interfaces or agent-assisted transactions. This work will assume increased importance as user competition rises over time.

The evolution of payments in India—the state of play

In recent years, India has moved to a leading position in digital payments and developed an ecosystem that enables the uptake and usage of digital payments. Many countries now seek to replicate India’s payments systems, particularly the Unified Payments Interface (UPI). This blog highlights the evolution of India’s payments landscape and looks into issues and ideas that contributed to this evolution. It briefly discusses the controversial waiver of the merchant discount rate (MDR) to increase the number of use cases in the person-to-merchant (P2M) category.

Digital payments in India have grown rapidly. Transactions increased from 23.4 billion in 2019 to 46.7 billion in July 2022, aided by several digital payment products, such as UPI and Aadhaar-enabled Payment Systems (AePS). The number of first-time digital payment users increased with these payments products, coupled with growing apprehensions about handling cash during the COVID-19 pandemic. Improvements in payments infrastructure, disruptions in information and communications technology, a responsive regulatory framework, a conducive policy environment, and a greater focus on customer-centricity have transformed India’s payments ecosystem.

Market offering or share of leading players—evolution over time

The major digital payment products available in India are Aadhaar-based payments such as Aadhaar Enabled Payments System (AePS) and BHIM Aadhaar Pay (BAP), contactless payments such as Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and Bharat Bill Payments System (BBPS), and card-based payments such as RuPay and debit card:

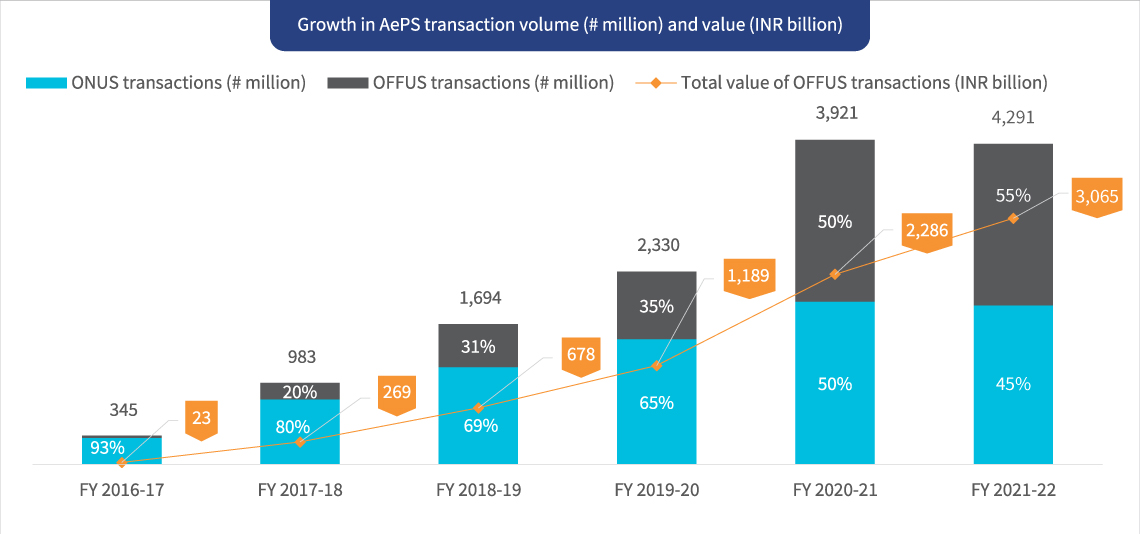

- AePS transactions increased by 290 million from 113.8 million in 2018 to 404.45 million as of July 2022 as people withdrew more money, thanks to increased domestic remittances and governments’ emergency cash transfer programs. AePS has boosted DBT payments in rural geographies with 407 million average monthly transactions. More DBT payments have led to the inclusion of users who do not own smartphones and need assisted services.

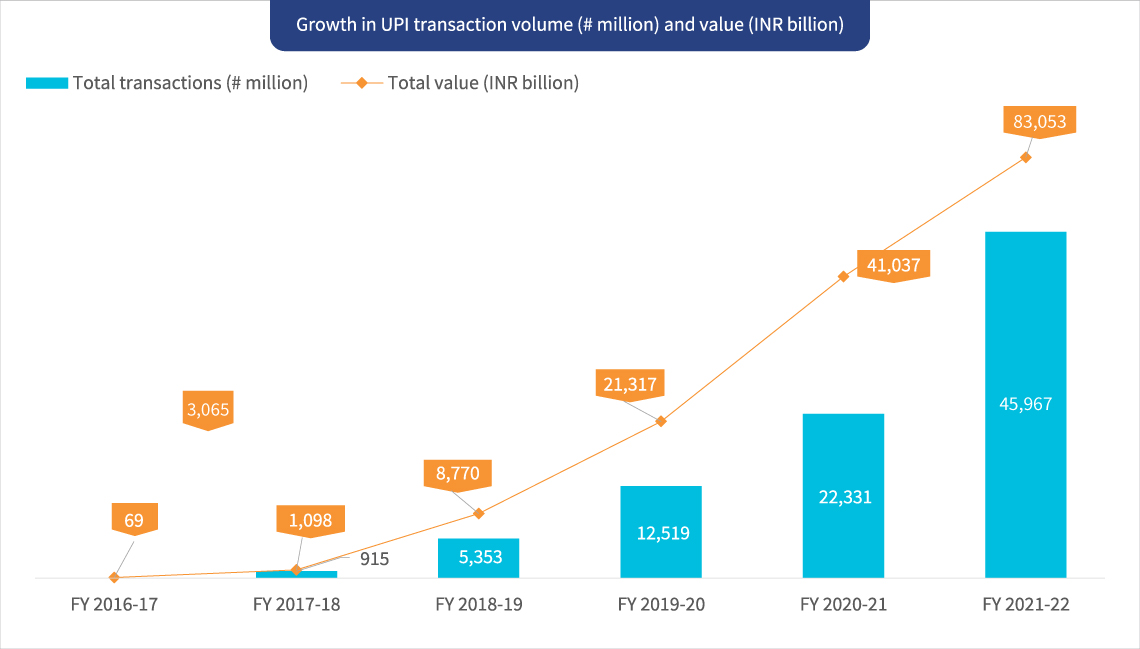

- UPI transactions grew at a CAGR of 119% and 138% by volume and value in the past five years, from FY 2017-18 to FY 2021-22. Today, UPI drives India’s digital payments with 300 million active users and 57 billion average monthly transactions. UPI offered one of the safest payment modes for person-to-person (P2P) and P2M transfers and outstripped all other payment platforms during the pandemic. In 2022, NPCI launched UPI123Pay, allowing feature phone users to use the UPI platform via Interactive Voice Response (IVR). UPI123Pay’s launch points toward the further adoption of digital transactions in the countryside, where most citizens still do not own smartphones.

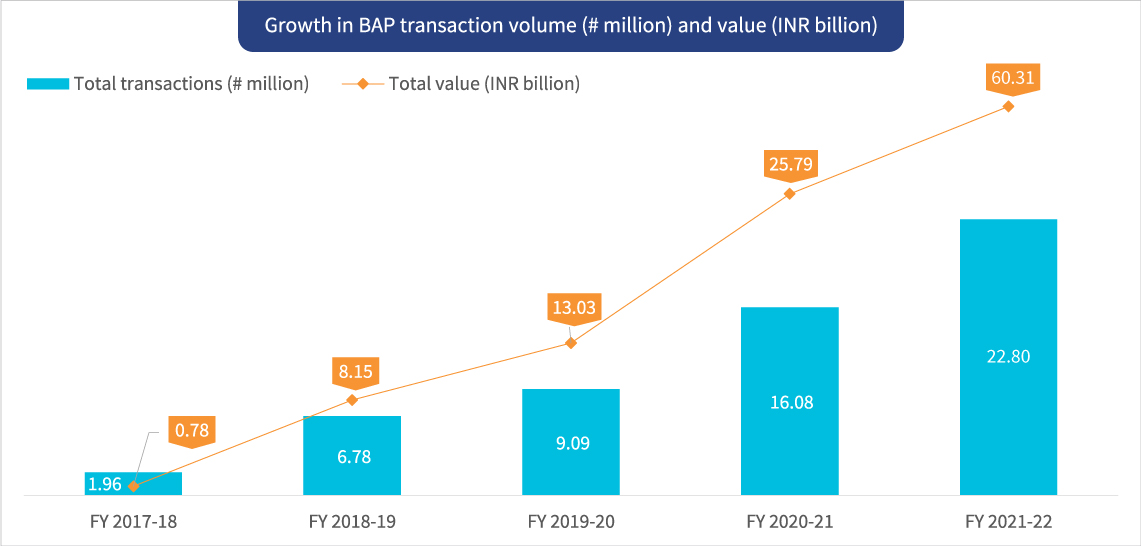

- BHIM Aadhaar Pay (BAP) is the merchant version of AePS. Unlike UPI, it enables merchants to receive digital payments from customers through Aadhaar authentication, whereas UPI requires customers to have a smartphone, UPI ID, and PIN. The transaction volume for BAP increased by 91% in the past five years. The average transaction value has risen steadily from INR 398 (~USD 5.38) in FY 2017-18 to INR 3,189 (~USD 39.92) in FY 2022-22, which indicates people are increasingly using BAP for large ticket-size transactions. The push from the acquiring banks and the cashback rewards available on transactions till December 2019, drove merchants and consumers to adopt BAP widely across semi-urban and rural India.

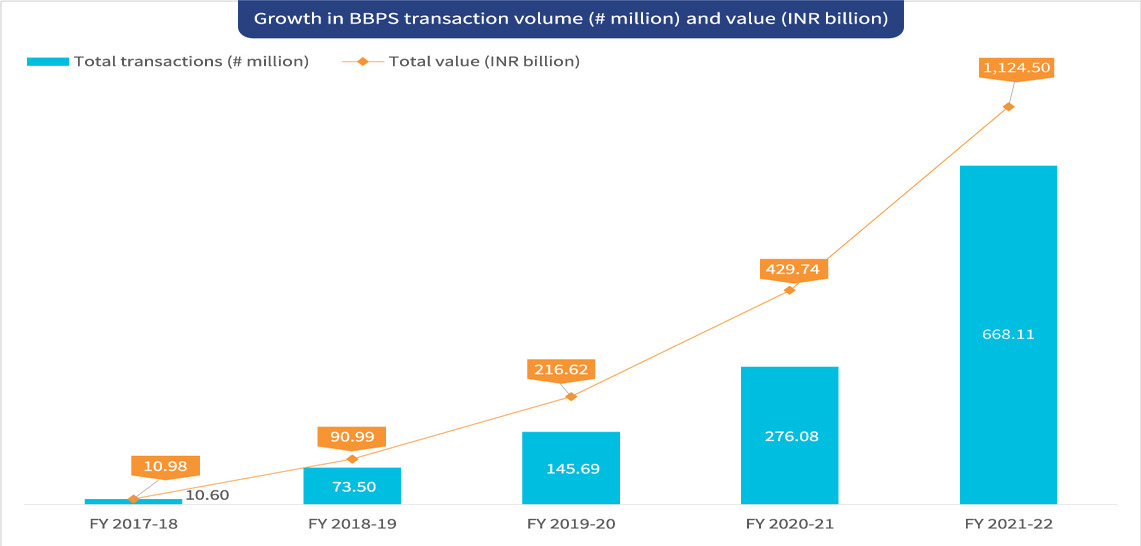

- Bharat Bill Pay System (BBPS) has consolidated India’s recurring bill payments industry under one payment system. It provides the convenience of round-the-clock bill payments to multiple billers from a single platform. Transaction volumes have grown significantly by 62% over the past five years, which indicates more customers now prefer BBPS for bill payments. By integrating recurring payments, BBPS has added 19,500 unique billers across 19 additional categories besides utility bills and airtime top-ups, such as education fees, loan repayments, insurance, fees for cooking gas, municipality taxes, and subscription fees.

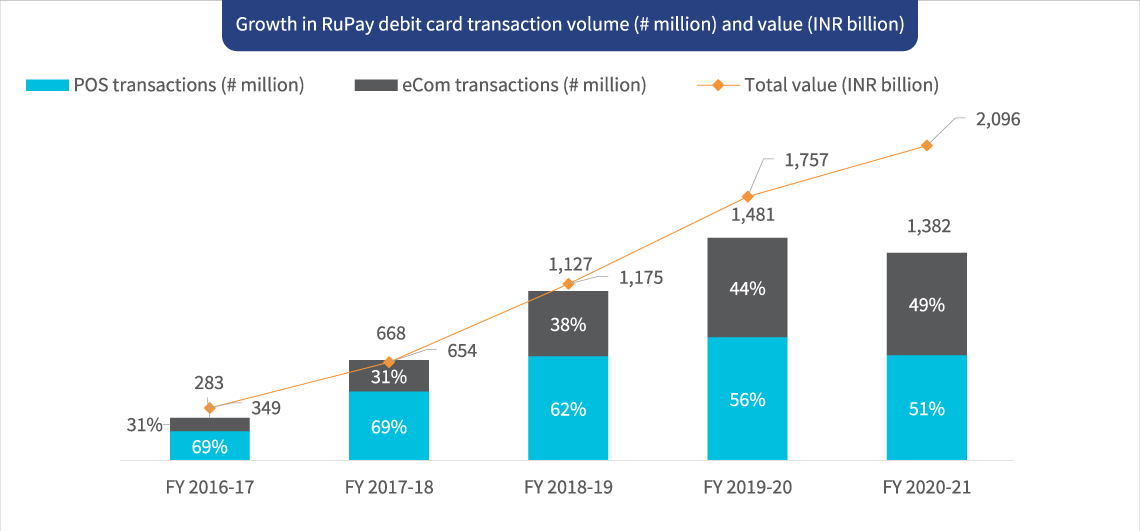

- RuPay is a homegrown card payment network. It offers low processing fees and wide acceptance at ATMs, PoS devices, and e-commerce across India. RuPay’s market share in total debit cards issued increased from 17% in 2017 to 60% in 2020. More than 1,224 banks have issued 94 billion RuPay debit cards. Transaction volume grew by 388% over the past five years. Both offline and online merchant payments remain significant use cases for consumers.

30% cap (of total volume) imposed by NPCI

The NPCI declared a 30% market cap on the total volume of UPI transactions for all third-party app providers (TPAPs) on 5th November 2020. The cap is calculated on a rolling basis per the total volume of UPI transactions during the preceding three months, starting on 1st January 2021. NPCI will inform all TPAPs over email once their total UPI transaction volume reaches 25% to 27%. Players will receive a second alert upon crossing the threshold of 27%.

Once players cross the threshold of 30%, they must stop onboarding new customers immediately. PhonePe, Paytm, and Google Pay continue to dominate the UPI market. They collectively hold 94.8% of the total UPI transactional volumes and 93% of the total value as of March 2022. This new policy on market cap was formulated and implemented to ensure that the UPI infrastructure offers a positive customer experience and discourages a handful of players from monopolizing the digital payments landscape.

QR code-based payments

India has approximately 750 million smartphone users, which is projected to reach 1 billion by 2026. The increasing affordability of smartphones, growth in the number of users in rural India, and government initiatives have grown India’s smartphone user base in recent years. Rural India has propelled this rise in smartphone use with a projected CAGR of 6% from 2021 to 2026. QR code-based payments can potentially create significant growth in digital payments, especially among customer segments with low financial literacy across India. With low infrastructure requirements, two-way transaction flows, secure transactions, and overall simplicity, QR codes offer an easy on-ramp to digital payments.

The COVID-19 pandemic aided the acceptability and uptake of QR code-based payments mainly due to their contactless nature, quick turnaround time, and ease of usage. So far, QR codes offer multiple use cases in both P2P and P2M transactions. Examples include toll tax payments, payments at grocery stores, mobile app downloads, and utility bills. They present a broader opportunity to increase use cases to allow more customers to pay using QR codes across various platforms.

Moreover, the regulatory environment in India is focused on open banking and making all QR code-supporting platforms interoperable. This interoperability enables customers to make payments across different FSPs, wallet players, and other platforms.

MDR

Policy initiatives, such as the waiver of MDR charges for providing financial incentives to promote digital payments, show the government’s intent to further financial inclusion through digital pathways. This initiative was expected to make onboarding merchants easier for businesses and influence more customers to adopt digital payments. However, the zero MDR policy hurt the payments ecosystem as it threatened the survival of several payment gateway entities, hampered innovation efforts, and slowed down India’s expansion of the digital payments infrastructure. This is demonstrated by RuPay’s performance, even though it commands 60% of the Indian debit card market, its monthly average transaction volume was less than 50% as against other debit cards in FY 2021.

Banks now hesitate to invest in improving their technology stack to smoothen the flow of digital payments due to the lack of incentives. The MDR may discourage players in the payments ecosystem from promoting digital payments. Therefore, some reimbursement or reconsideration may be needed to prevent this.

Future opportunities

India’s payments ecosystem is in good health. With the boost that COVID-19 provided, it is poised for further growth. The following blog in this series examines the future and opportunities to further turbo-charge the growth of digital payments in the country.

Grievance redress mechanisms in welfare programs: A milestone yet to be achieved

“Calling on the toll-free numbers does not help, as most of the time, the numbers do not work or the call disconnects. Visiting government offices is the only way for us to register grievances.”

– A National Pension Scheme beneficiary in India

“We have to visit the offices several times without knowing the point of contact or where to raise our grievances. We often return without getting any resolution, losing a day’s wage.”

– A PM-KISAN beneficiary from the state of Madhya Pradesh

Many Indian citizens receive social security from government-backed schemes—a term used in India for large-scale programs. The Government of India relies heavily on Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) schemes to deliver the scheme benefits to people who need them most. Yet many beneficiaries across India’s far-flung corners face a barrage of challenges linked to unresolved grievances, which lead to their exclusion from the schemes altogether.

Why do beneficiaries of welfare schemes struggle with grievance resolution?

Like many government bodies, the Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances established a process to resolve grievances at the central level. These methods to manage grievances are known as Grievance Redress Mechanisms (GRM) in South Asia. Yet its effective implementation falls short. MSC’s evaluation of many DBT schemes suggests that existing systems to resolve grievances are not robust enough to respond to the many challenges faced by beneficiaries.

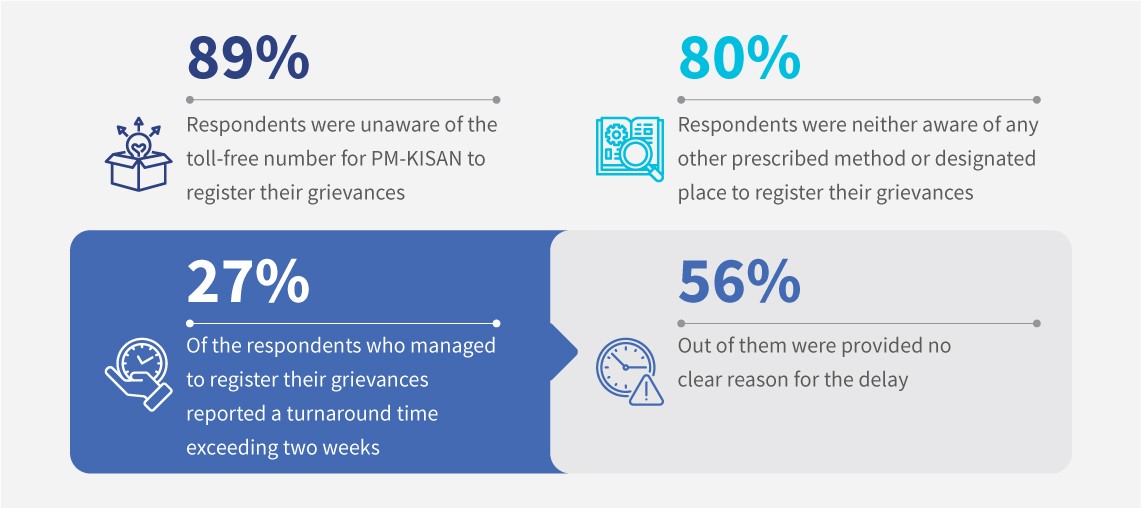

Source: MSC’s evaluation study of PM-KISAN

This blog compiles data on the state of GRM from the study of DBT schemes alongside observations from corresponding field visits. We document challenges with the GRM systems and suggest ways to transform them into more beneficiary-centric mechanisms.

4-A: The pain points:

The “4-A pain points” framework elaborates on the major challenges the beneficiaries face to get their issues resolved:

Awareness:

Awareness:

Many beneficiaries remain in the dark regarding grievance registration and resolution. They are not informed of the dedicated portals, toll-free helpline numbers, or other channels of grievance resolution launched by the government. An assessment of DBT in Education in Uttar Pradesh, India, reports that 83% of respondents who did not complain about failure to receive benefits did not know of the concerned channel to resolve their grievances.

Accessibility:

For many DBT schemes, the government helpline numbers are inactive. The beneficiaries lose wages as they travel long distances and search frantically for the relevant authorities at the block (sub-district) or district offices. Many beneficiaries choose to forgo registering their grievance due to these accessibility issues. “The district office is more than 15 km away from my village. It becomes difficult to travel such long distances and register a complaint at the cost of my work,” says Murali, a farmer from Rajasthan, who missed his last two installments of the PM-KISAN scheme.

Availability:

Dedicated, beneficiary-centric GRM units to address the beneficiaries’ grievances are absent. “We lack designated offices close to our village that could solve our issues. We are told to visit the block office, but we are unaware of the point of contact,” notes a PM-KISAN beneficiary farmer from Chhattisgarh. When the beneficiaries approach the concerned officials, their issues remain unsolved. The officials are frequently swamped with other administrative priorities and fail to solve their problems or even provide guidance.

Accountability:

The current GRM for welfare schemes does not place accountability on the supply-side stakeholders. Most GRM systems used in DBT schemes lack a standardized operating procedure (SOP) to resolve grievances. Although the system has in place essential components, such as a standard turnaround time (TAT), escalation matrix, and feedback mechanism—beneficiaries fail to use these to their advantage. For example, the PM-KISAN guidelines mention a TAT of two weeks for the registered complaints. But our study suggests that many beneficiaries had unresolved complaints for months, even after they approached concerned authorities. They did not know about the TAT and their rights to escalate the problem.

How to tackle these pain points?

The following recommendations would help build responsive and beneficiary-centric GRM systems:

1. Below-the-line advertising: An important tool to spread information

Currently, communication campaigns for the DBT schemes focus on mass marketing strategies, such as hoarding and banners at prominent locations and advertisements in the electronic media, rather than through awareness-building at the individual level. Below-the-line advertising strategies, such as customized pamphlets and SMS in the regional language, could help in better penetration of the information at the individual level and improve the rate of grievance registration. The SMS that beneficiaries receive on benefit transfer can also include additional information on channels to register grievances and guidance on using them

2. Setting up local grievance resolution centers for improved accessibility and availability

One step is to use the nationwide network of 373,877 Common Service Centers (CSCs) as GRM centers. Our study suggests CSCs are the critical point of contact where digitally illiterate beneficiaries extract information on the status of their application or reasons for non-receipt of scheme benefits. These centers can be equipped and empowered to make specific basic edits to beneficiary records. For example, they could be empowered to update the Aadhaar details, contact number, and errors in application forms. However, providing access to beneficiary data to CSCs must not happen at the cost of privacy, and the SOP needs to specify this clearly. The vast CSC network can save beneficiaries the effort and time of visiting a government office with grievances. The 140,000 India Post branches could also be used for this.

We can also draw inspiration from the Rajasthan Government’s flagship “Prashasan gaon ke sang” campaign, under which camps are set up to provide local access to government services and resolve grievances in the remotest villages of the state. These camps give people access to 22 government departments for immediate identification and resolution of issues related to government schemes and services. The “e-mitra” kiosks are also present to facilitate any immediate online formalities related to the schemes. These camps serve as a one-stop destination for citizens who face issues of inaccessibility, digital illiteracy, and lack of information on resolving grievances. Such mobile GRM units can be replicated across states to offer an accessible and approachable mechanism of grievance redress for the G2P DBT schemes.

3. Revamping the grievance management portals and setting up accountability mechanisms

An SOP should be prepared to outline the processes to resolve grievances for these schemes clearly. It should contain clear guidelines on TAT for grievance resolution, the escalation matrix, and a feedback mechanism. The introduction of an escalation matrix would speed up the resolution process and inculcate a sense of accountability among the officials. This would also help the state GRM cell monitor the complaints regularly, ensuring a seamless process flow. The feedback mechanism will help understand the beneficiary experience and gauge their satisfaction level.

A Complaint Management System (illustrated above) should be introduced to make grievance redress transparent. This system is similar to the process flow of the Central Public Grievance Redress and Monitoring System (CPGRAMS)

A “State GRM Ranking” could be prepared based on regular audit and monitoring results. Such an initiative would encourage a spirit of competition among the states and ensure effective grievance resolution at their level. The best-performing ones could be incentivized, and training and learning sessions can be structured for laggard states.

The Government of India has recently announced its commitment to target 100% coverage of welfare schemes. The recommendations in the blog are ambitious. Yet if implemented, they could significantly improve the GRM system for DBT schemes in the country and thus speed up the maximum inclusion of beneficiaries.