MSC conducted an assessment with the Department of Basic Education in Uttar Pradesh, India, on the transition of the mode of delivering school supplies to primary and upper primary school students from in-kind to direct benefit transfer (DBT). The study intended to examine the effects of this transition on teachers, who expressed concerns about the excessive burden associated with facilitating the distribution of supplies in the previous in-kind mode. This briefing highlights the challenges teachers face and emphasizes how the DBT mode will prove transformational, enabling teachers and students to prioritize their respective academic goals.

Digital financial capability—using emotions to design content

We were in the middle of a digital financial capability (DFC) session in the Kerwari village of Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. Our team was conducting an interactive activity to help rural women understand how to make digital transactions using a mobile phone. In the middle of the activity, Revati, a participant, called out and asked us, “What is the use of teaching us all this when we all know is that we are scared of using mobile phones to make payments.”

Figure 1: Picture from fieldwork in Kerwari village Figure 2: User interface prototypes for mobile applications, for activity purposes

Awestruck by Revati’s question, we brainstormed a possible solution after the fieldwork ended. However, it took us a while to realize that we might have to delve deeper to address some critical behavioral issues Revati brought to light.

MSC’s study and other studies also highlight the importance of behavioral biases in adapting financial services. One of the objectives of DFC interventions is to increase the user’s confidence in using digital financial services independently and skillfully. This confidence enables them to protect their money against fraud, safeguard their data, and understand and use digital interfaces.

Moreover, based on our experience working with multiple providers, we understand that providers focus considerably on increasing the user’s confidence by upgrading user knowledge and skills but often focus little on changing the user attitude. A user’s attitude includes attitudes toward accessing or using digital financial services (DFS) and their risks. It also includes attitudes toward a greater need for DFC after COVID-19. Therefore, a strategic focus on intuitive content design (detailed below) and compatible delivery (described in this blog) will help practitioners build better DFC interventions to change attitudes.

Research also reveals that attitudes based on emotions can stand the test of time, and these emotions are essential for financial decision-making. Emotional designs result in a positive user experience. DFC content with emotional designs nudges users to convert long-lasting attitudes or beliefs into actions. Don Norman mentions that the emotional system comprise three different yet interconnected levels, each influencing our experience in a particular way. The three levels are visceral, behavioral, and reflective, and DFC content that caters to all these levels should impact attitudes.

Figure 3: Best practices to design DFC content using emotional design

Level 1: Visceral

Visceral aspects form the first impression of the DFC content. Visceral aspects focus on appearance, including expressive colors, immersive sounds, and intuitive touch. The solution’s visceral quality establishes its first emotional connection with the target segment. The visceral design also helps build trustworthiness and gain traction from the target segment. For DFC interventions, visceral aspects are often presented as attractive and colorful animated videos, comic books, and cartoon strips. However, the target segment must relate to these representations, or they may lead to an instant emotional disconnect.

MSC used its years of experience of managing business correspondent (BC) outlets and a deep understanding of their needs to help personify characters and set context as per actual interactions for animation video designs. The video appearance immediately connects with BCs at a visceral level. These videos developed with funding from the World Bank are currently in use to train BCs registered with BCFI. BCFI is a federation with a membership of more than 200,000 BC agents in India that uses the platform to skill and re-skill agents.

MSC used its years of experience of managing business correspondent (BC) outlets and a deep understanding of their needs to help personify characters and set context as per actual interactions for animation video designs. The video appearance immediately connects with BCs at a visceral level. These videos developed with funding from the World Bank are currently in use to train BCs registered with BCFI. BCFI is a federation with a membership of more than 200,000 BC agents in India that uses the platform to skill and re-skill agents.

Level 2: Behavioral

The behavioral level is about usability. It refers to the content’s practical and functional aspects that help change behavior. Good behavioral design is like a lock and key. Customer behavior is the lock, content is the key, and harmony exists when the two work smoothly. Conventional DFC content focuses on imbibing behavior toward budgeting, opting for cheaper loans, or registering for insurance. However, the vulnerable income groups have volatile income and expenses. Therefore, financial decisions focus less on creating a stable budget and more on making ends meet.

MSC’s support to HFC Kenya resulted in the use of behavioral design to integrate DFC into its mobile banking application’s user interface. The MSC team used their proprietary Market-Insights for Innovation and Design (MI4ID) approach to redesign the menu options in the application, which focused on use-cases, such as borrow, invest, spend, store, and protect, making the user interface more intuitive. In addition, they simplified the interface with calculators to help budget for deposit and credit requirements so that the mobile application can also help improve customers’ overall financial health.

We can use a few high-impact emotional biases to influence behavior through DFC content design:

- The vulnerable segment is more sensitive to small losses than significant gains. Loss aversion explains why people deposit their money with local groups rather than banks. Thus, they avoid losing prospective financial support from their communities in times of need;

- Most financial service users exhibit status quo bias and are motivated to try DFS for the first time only when it negatively affects their reputation;

- The user seeks social proofing from a trusted person before using DFS;

- Scarcity bias is a predominant bias among the vulnerable segment leading to an ongoing struggle to deal with limited resources at the expense of planning long-term goals.

Please note this list is not exhaustive. We have listed only a few common behavioral traits of the LMI segment, and each customer segment has specific characteristics.

We use our understanding of behavioral science to develop interactive nudges or counter-arguments addressing behavioral biases. However, we must understand that the content’s usability differs widely among target segments. For example, the content presented as a gaming application may serve literate youth adequately, while a simple IVR-based solution can prove complicated for illiterate rural women. Read the next blog in this series to learn more about various channels for DFC programs in detail.

Level 3: Reflective

Reflective content is the highest level of a design’s emotional state, which helps the target segment instill a deeper meaning in the content as it directly impacts their System 2 thinking. The target segment consciously approaches the presented content, weighs its pros and cons, and extracts relatable information. This level also addresses deep-rooted fears among the target segment related to DFS and helps them identify how to overcome them.

We use heuristics to simplify complex decision-making to help target segments further rationalize the presented content. While developing content for a community-led DFC intervention, MSC developed a meaningful and straightforward rule of thumb to help entrepreneurs retain essential information, which translated to changes in how they use financial services. MSC also trained the Financial Service Providers (FSP) staff as mentors to help them use this rule.

Jagruti is a volunteer-based low-cost DFC model currently piloted in a district of Uttar Pradesh, India, as part of an intervention by NITI Aayog.

Jagruti is a volunteer-based low-cost DFC model currently piloted in a district of Uttar Pradesh, India, as part of an intervention by NITI Aayog.

The pilot design includes the following:

- Carefully crafted prototypes for experimentation. See women participating in an ATM prototype exercise in the picture on the right.

- Content aligned to overcoming cultural fear by disseminating content through activities for the group to solve, helping inculcate DFS usage into daily lives.

Further, the pilot is expected to help build confidence among low-income women and the farmer population for DFS usage.

A DFC intervention that incorporates all three emotional design levels into the content of the DFC solution can help users like Revati absorb DFC content better for the effective use of DFS. Therefore, an ideal DFC intervention will include an attractive, easy-to-use solution incorporated into daily chores. The intervention should focus explicitly on incorporating social proofing to address the fear of conducting DFS transactions for Revati and countless others like her.

Read our next blog that identifies appropriate digital channels to disseminate DFC content that triggers all levels of our emotional system.

How can digital public infrastructure improve government-to-person payments?

In Sub-Saharan Africa, millions of impoverished, at-risk individuals struggle to access essential services, such as banking, agricultural financing, and social protection. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the urgency of digitally delivering these services, ensuring support for individuals, businesses, and governments. Imagine living in their shoes as you navigate a world where these resources are crucial to survival.

Now imagine these services are all connected in a digital ecosystem. They are scalable, innovative, and inclusive for all. What is the cornerstone for such a digital revolution? The answer is digital public infrastructure.

Why is DBTs crossed?

Digital public infrastructure or DPI refers to digital solutions and systems that enable the delivery of society-wide services to citizens and businesses in a secure, reliable, and democratic manner. We may compare DPI to physical public infrastructure, such as highways, which facilitate travel to benefit citizens, businesses, and governments. Similarly, a repository of authentic and verifiable beneficiaries of government-to-person (G2P) payments is a DPI. It digitally enables the G2P social benefits to eligible citizens.

The implementation of DPIs has grown significantly in the past few years and enabled countries to achieve digital inclusion and empowerment for their citizens. DPIs have also created opportunities for new business models, social innovations, and public service delivery. In the coming years, they are likely to see significant growth.

DPIs are most effective when they interoperate with other systems, serve the evolving needs of their users, protect the privacy and security of users’ information, and promote innovation on top of foundational systems.

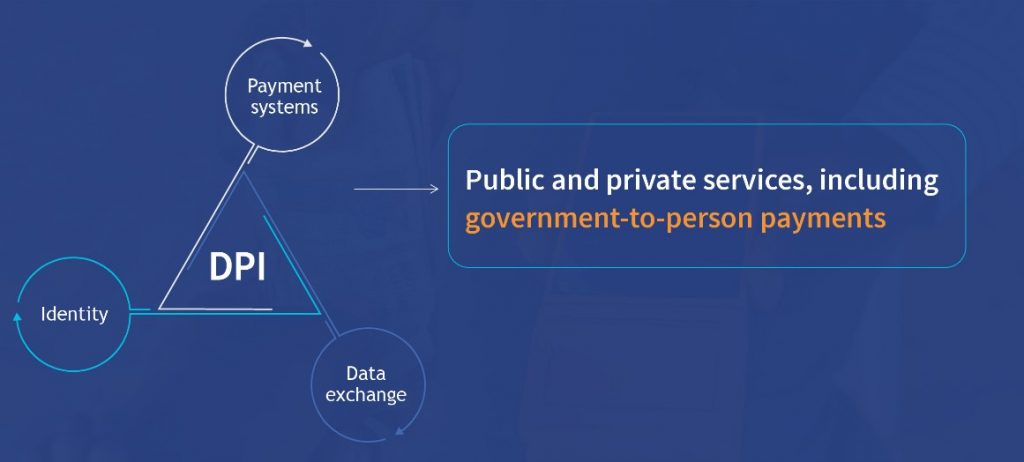

DPIs underpin a robust and inclusive digital ecosystem, and its three essential pillars are identity, data exchange, and payments. Digital identity captures citizens’ information, which uniquely identifies and authenticates them. Data exchange facilitates secure and prompt information sharing across systems. Payment systems enable seamless financial transactions. In an inclusive digital ecosystem, these three pillars help governments deliver benefits or services seamlessly to eligible citizens in an open and transparent manner.

India’s digital public infrastructure

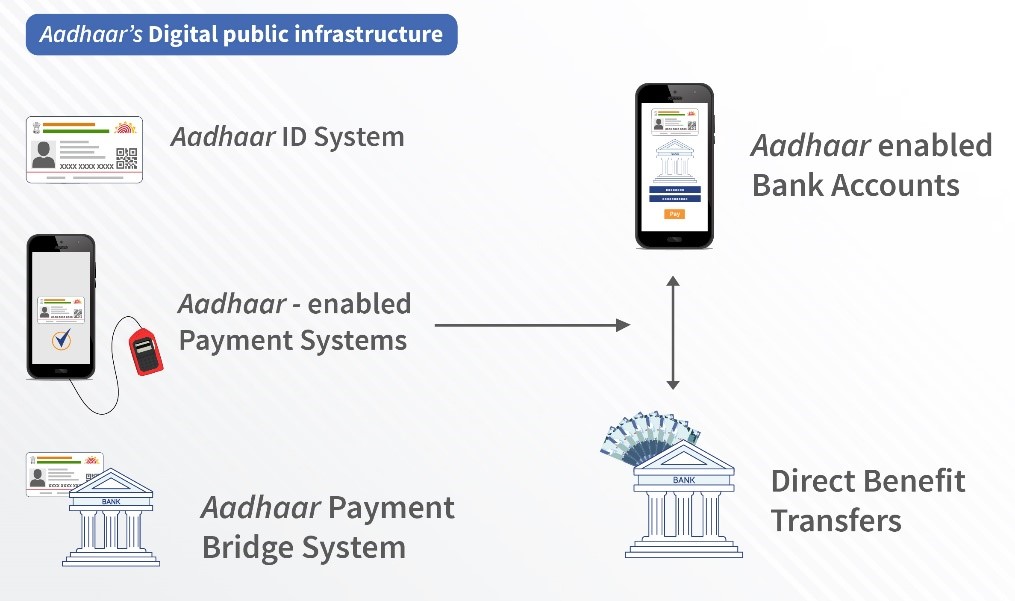

India illustrates how combining DPI’s pillars can effectively digitize G2P payments. Aadhaar, India’s foundational digital identification system, has 1.365 billion users—more than 90% of the country’s population. It captures each user’s information in a unique 12-digit ID number. The unique number’s information is shared using data exchange with service providers to enable services, such as bank account opening.

Aadhaar-enabled bank accounts (AeBA) then interoperate with the Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS) to authenticate Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) beneficiaries. Then, another payment system, the Aadhaar Payment Bridge (APB) system, uses the Aadhaar number as a central key to send social benefits to the intended beneficiaries’ AeBAs. DBTs are subsidies paid directly to their beneficiaries’ accounts. Three hundred eighteen programs from 53 ministries use DBT, which accounted for 5.94 billion transactions worth a combined INR 6.24 trillion (USD 76.34 billion) in FY 2022-23.

The LPG (cooking gas) subsidy program benefitted from DPIs. The government linked subsidies directly to their beneficiaries’ bank accounts with MSC’s technical assistance. This linkage removed about 35.6 million duplicated or “ghost” beneficiary accounts from the LPG program and saved the Indian government USD 3.23 billion. The government redistributed these savings to its Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) initiative, which benefits nearly 90 million households.

Kenya’s digital public infrastructure

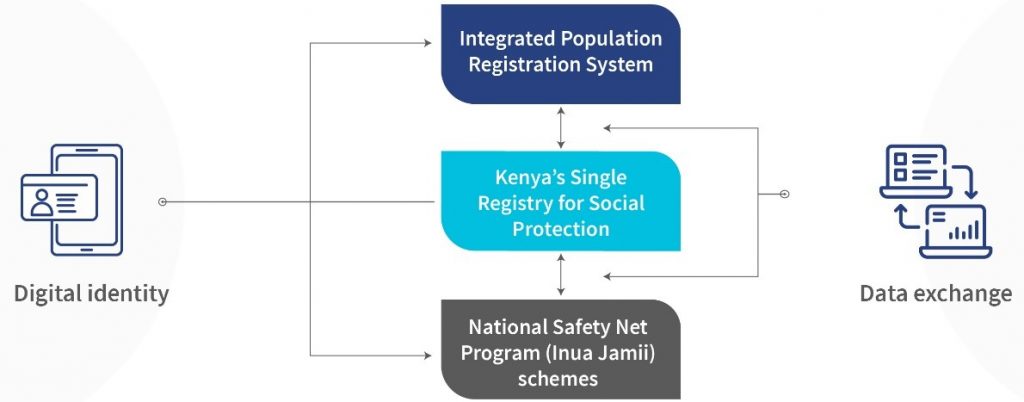

Kenya’s National Safety Net Program, commonly known as Inua Jamii, is an example from East Africa to illustrate the potential for digitized G2P payments through DPI’s three pillars. Inua Jamii is an umbrella program for various transfer programs that use selected payment service providers (PSPs) to transfer social protection to beneficiaries.

Before the payments can be disturbed, the PSPs use digital identity to authenticate beneficiaries via biometric data and national ID cards. This authentication uses data exchanged between Kenya’s Single Registry, which unites beneficiary information from all Inua Jamii’s programs and its Integrated Population Registration System (IPRS). Additionally, the registry collects beneficiaries’ data during the programs, such as registration, enrolment, payments, and grievance management records. It serves as an intermediary between these programs and the IPRS.

Digital payment systems enable fund transfer from the National Treasury to the State Department for Social Protection’s Social Assistance Unit to each selected PSP and finally to the beneficiaries’ accounts using Kenya’s electronic payments infrastructure. The unique combination of these DPIs is relatively new, yet significantly, it helped the Kenyan government disburse KES 8.54 billion (USD 62.94 million) to 1.07 million beneficiaries in January 2022.

Zambia’s digital public infrastructure

Zambia’s government digitized cash-based interventions (CBI) for refugees in the Meheba Refugee settlement camp in collaboration with UNHCR, UNCDF, and MSC. The initiative registered eligible beneficiaries with SIM cards and provided them with digital wallets and PINs. Their mobile numbers and digital wallets were updated in ProGres, the government refugee database, which authenticated them before they received payments through the digital wallets.

Digitized CBI was pilot tested after MSC assessed the previous method’s challenges. Upon its implementation, 52% of CBI payments occurred using digital wallets. The distribution time was reduced from an average of 13 days to 2.5 days. This model is now used to digitize most refugee payments in Zambia.

Nigeria’s DPI opportunities

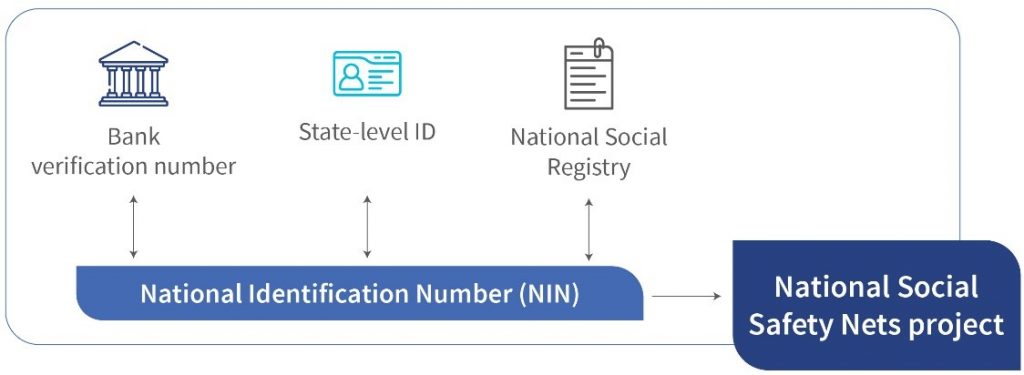

Sub-Saharan Africa offers many opportunities for DPI-enhanced G2P payments, as illustrated by Nigeria’s National Social Safety Nets Project (NASSP), which contains various G2P programs. These programs store the information of their 61.6 million eligible beneficiaries in a National Social Registry (NSR). NASSP beneficiaries can be authenticated using various IDs, such as national identification numbers (NINs), state-level IDs, or bank verification numbers (BVNs), using each ID’s corresponding ID database. Then the National Cash Transfer Office (NCTO) transfers funds to select financial service providers (FSPs) via the Remita e-payment system. These FSPs credit virtual accounts that beneficiaries must cash-out from using NFC (near-field communication) cards and QR codes.

NASSP’s process has specific core infrastructural challenges. NASSP lacks a standardized ID authentication process. Nigeria’s bank verification numbers are not fully integrated into its foundational ID—the NINs. If BVNs were NIN-enabled, they could be used to open accounts for beneficiaries. Furthermore, if the NIN’s database, which has 97.5 million users, were linked to the NSR, it would streamline beneficiary authentication through data exchange between NIN, NSR, and the BVN, which has 57 million users.

Lessons, challenges, and the way forward

Cases from Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia provide insightful lessons on the challenges within DPI-enabled G2P payments, which could help build an understanding of how DPIs can improve G2P payments. Various technologically capable parties, including government bodies, must collaborate to deliver these payments. While agent networks can provide vital assistance, G2P beneficiaries should ideally be digitally literate and equipped to receive and use payments. However, payment delivery must suit their needs and preferences.

Governments must combine identity, data exchange, and payment solutions to implement DPI-enabled G2P payments across Sub-Saharan Africa effectively. Digital identity must capture eligible beneficiaries’ information. It must combine with data exchange to integrate this information into national identity databases and authenticate these beneficiaries. Data exchange must connect with payment systems for financial service providers to give beneficiaries digital accounts that receive G2P payments. Governments and their partners must assess beneficiaries in the initial design and evolution phases, as MSC did for Indonesia’s largest digitized G2P initiative, Bantuan Pangan Non Tunai (BPNT). Additionally, governments must collaborate with the best partners to execute each phase of this process, both from the public and private sectors.

This blog raised the need to digitize G2P payments and other services for millions of impoverished individuals. In India, Indonesia, Kenya, Nigeria, Zambia, and across Sub-Saharan Africa, evidence shows that DPIs have been and will be vital to this. Solutions providers are creating DPIs, service providers are implementing them, and thought leaders are analyzing and technically assisting with them. It is time for all the players to come together, maximize their collective understanding and usage of DPIs, and create the digital revolution the impoverished millions desperately seek.

Voices of India’s MSMEs: Insights notes from the diaries access to finance

The third in this series of notes, Insights note-Edition 3, covers aspects related to the status of access to finance among India’s informal enterprises (IEs). Despite several initiatives by the Government of India, access to finance remains a critical issue among IEs due to several challenges that this note delves into.

The note discusses examples from MSC’s Financial Diaries research on IEs to validate the findings. It also provides recommendations for policymakers and financial service providers to address the credit gap for IEs.

Can Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs) benefit from participating in agriculture derivatives trading?

In May 2022, as market trends indicated rising prices for maize, Aranyak Agri-Women Farmer’s Producer Company Limited (AAPCL) used the National Commodities and Derivatives Exchange (NCDEX) futures market to make an additional $1,875 (INR 150,000) profit on their sale of maize.

Policymakers in India view the trading of commodity derivatives sceptically, and as a result, have enacted occasional bans and suspensions. Unfortunately, this apprehension is often misplaced and appears to be driven by concerns around speculative trading and market price manipulation. However, there is a growing trend among farmer-producer companies to utilize commodity derivatives trading to establish market linkage, achieve better price realization, and/or hedge commodity price fluctuations. In fact, over the last five financial years (FY 2016 to present), NCDEX has successfully onboarded 470 FPCs, with 160 of them trading a total of 115,175 metric tons (MT) in 18 different commodities.

The NCDEX and Multi-commodity Exchange (MCX) are the two major derivative exchanges in India, including futures and options contracts. Futures contracts allow buyers to purchase a commodity at a pre-determined price at a specific point in the future, while options contracts give the owner the right to sell (put option) or buy (call option) the underlying commodity/asset at a pre-decided price. One major difference between futures and options contracts is that the buyer or seller is obligated to buy or sell the good at the predetermined price upon contract expiration, whereas options holders have the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell. In India, FPCs are allowed to deal in both futures and options. MSC through our work with FPCs, has facilitated 2,100 MT of maize futures trades and 1,200 MT of options trades in maize, chickpea, and mustard seeds. In this blog, we highlight our experience in supporting FPCs, trade in the derivatives markets, as well as the opportunities and challenges they have encountered as a result. For the purpose of this blog, we are only concerned with delivery-based trades, which is derivatives trading accompanied by the physical transfer of commodities upon contract expiration, and not speculative trades.

How FPCs can benefit from derivatives trading?

Derivatives markets as a way of institutional market linkages for FPCs

FPCs can benefit from futures contracts in several ways, one of which is by leveraging arbitrage opportunities between the spot market price which is the current market prices, and future prices reflected on commodity exchanges. Commodity exchanges have the potential to attract a larger set of buyers than traditional spot markets, due to the sheer size and volume of what is being traded, providing opportunities for FPCs to obtain some arbitrage opportunities than they would get in the open markets.

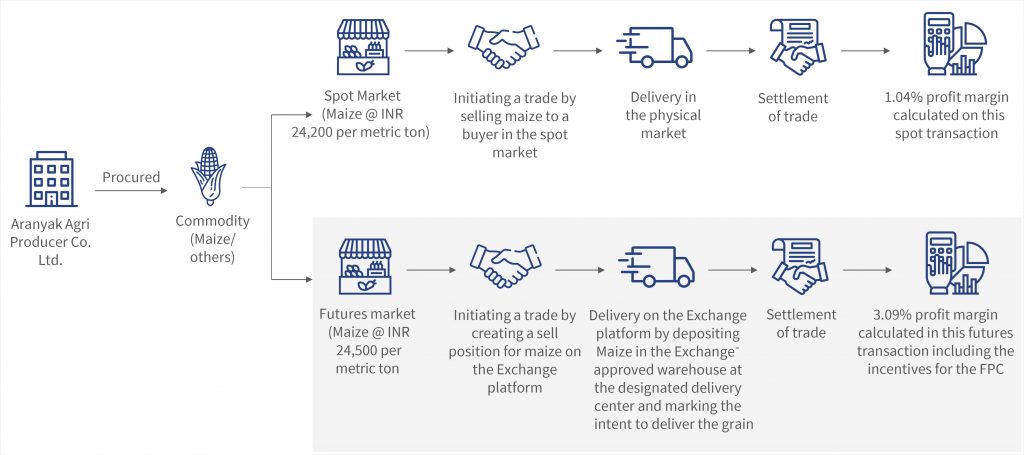

For an example, let us return to the case of Aranyak Agri-Women Farmer’s Producer Company Limited (AAPCL), which operates in Purnea, Bihar, and works with maize farmers. During the maize season from May to June, the FPC had the opportunity to trade maize August futures on the NCDEX exchange at USD 306.25 /MT (INR 24,500/MT), while the prevailing spot market rate was only USD 302.5 /MT (INR 24,200/MT). In essence, market forces indicated that the price for maize was going to rise, resulting in a price in the futures that was higher than the current metric ton price. By trading on NCDEX, the FPC was able to obtain a gross margin of 3.09% on the transaction, compared to the 1.04% margin it would have received if it sold in the spot market. There are additional expenses incurred by the FPC to deliver on the platform such as transportation costs till the NCDEX delivery centre and assaying costs at the NCDEX accredited warehouse. However, AAPCL benefitted from the subsidies offered by the regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and NCDEX to FPCs to encourage their participation in derivatives trading.

Figure 1: Delivery based trade of AAPCL using futures contract

Price risk management using futures contracts

FPCs can effectively manage the price risk of stored commodities by using futures contracts without participating in deliveries on the commodities exchange platform. This approach can be particularly useful as explained in the following scenarios:

- When the exchange’s delivery center for a particular commodity is unavailable in the FPC’s intervention area. For example, NCDEX has a delivery centre for only maize in the entire state of Bihar. So, for other commodities FPCs may have to send the produce to other states.

- When the cost of delivery-based trades on the exchange is higher than selling in the nearest physical market.

- When storing commodities at the exchange’s warehouse is not logistically feasible or too expensive.

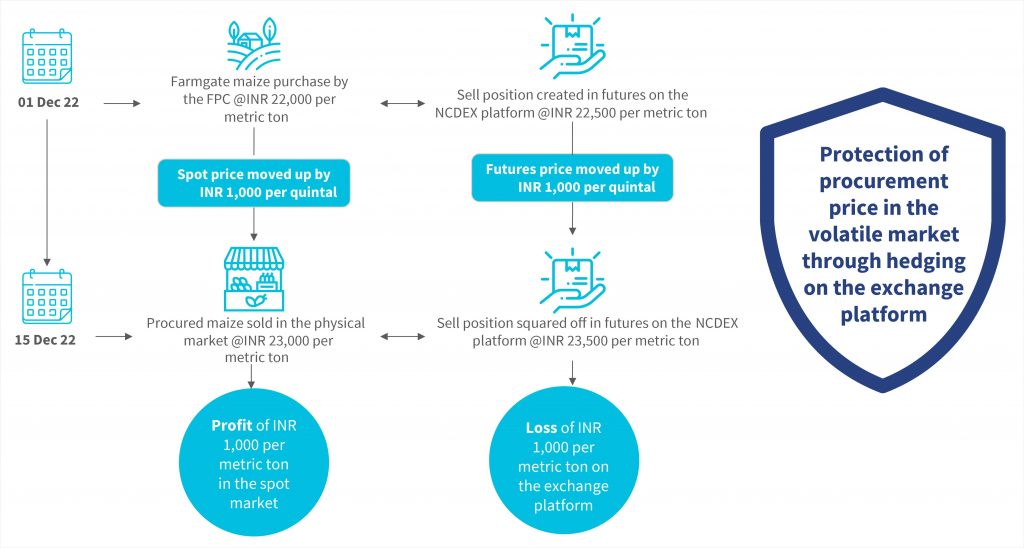

To illustrate the hedging mechanism, using a hypothetical company, ABC, consider the following example. On December 1, 2022, FPC ABC purchases maize from its shareholders at USD 275/MT (INR 22,000/MT). To hedge against potential losses, the FPC enters into a futures contract to sell maize on the NCDEX at USD 281.75/MT (INR 22,500/MT). On 15-Dec-22, the spot market price for maize became USD 287.75 /MT (23,000 /MT) and the “buy” rates in the futures market also moved up to USD 293.75 /MT (INR 23,500 /MT). The FPC sells the procured maize at USD 281.75/MT (INR 23,000/MT) in the nearest physical market, resulting in a profit of USD 12.5/MT (INR 1,000/MT). Simultaneously, the FPC closes out its sell position by buying a futures contract at USD 293.75/MT (INR 23,500), incurring a loss of USD 12.5/MT (INR 1,000/MT). In this example, the FPC does not realize a net gain or loss on these transactions but effectively protects the initial purchase price of USD 275/MT (INR 22,000/MT) from potential market price losses.

Figure 2: Price risk management using futures contracts

Price hedging through Put Options contracts

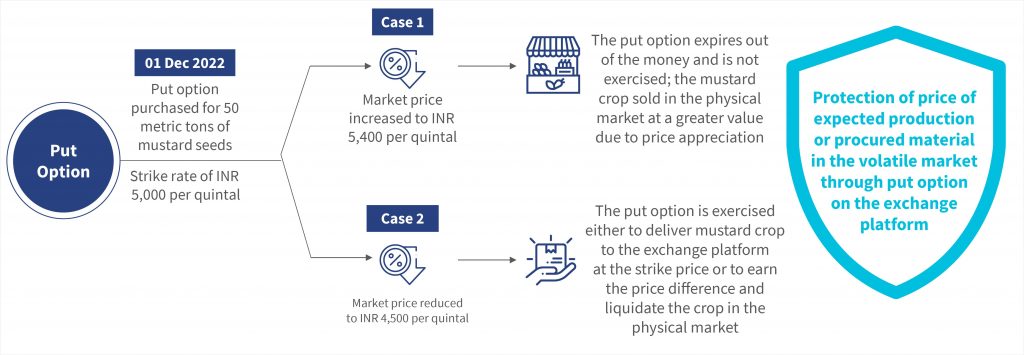

As previously mentioned, a put option, giving the holder the right to sell a good at a specified price by/on a specified date also serves as a valuable tool for hedging against price risks. For example, FPC ABC dealt in mustard seeds during the production season and purchased Put options on the 1st of December for 50 MT at a strike price of USD 62.5 /MT (INR 5,000/MT) via the NCDEX platform. This strike price represents the price at which FPC ABC can sell its mustard seeds if it chooses to exercise its put option. This put option was set to expire on January 25th. At the end of the season, the price of mustard seeds had risen to USD 67.5 /MT (INR 5,400/MT), allowing the FPC to sell the commodity in the spot market and earn a profit, while also squaring off the outstanding Put option at no additional cost. Alternatively, if the price of mustard seeds had fallen below USD 62.5/ MT (INR 5,000/MT), the FPC could have executed the trade on the NCDEX platform and made a profit. By following this process, the FPC was able to lock in a price for the commodity prior to the harvest season. The cost to purchase the Put option, also known as the premium, was around 6% of the total trade value, the FPC was able to take advantage of a 100% subsidy on the premium amount provided by SEBI to encourage Options trading by FPCs.

Figure 3: Price risk management using Options contracts

Other benefits of trading through exchanges

Exchanges are organised and supervised market places and trading through them offer a number of benefits to FPCs such as:

Reduced counterparty risk: Derivatives trading is supervised by the commodities exchange, which ensures that all parties involved in the trade meet their obligations. FPCs do not have to worry about receiving payment and buyers do not have to worry about the quality of materials supplied. These issues are common in spot market trades.

Price discovery and transparency: Derivatives markets are a good source of price discovery of agricultural commodities. FPCs can get a trend of the prices that the market is headed towards and can plan accordingly. Prices in the derivatives markets are clearly laid out, and FPCs do not face the ambiguity that they often encounter when dealing with traders and some institutional buyers.

Our next blog in the series considers the five key challenges that prevent greater adoption of derivatives trading by FPCs.

Overcoming challenges in Farmer Producer Company (FPC) scaling and sustainability: Lessons from JEEViKA in Bihar

The Government of India’s 10,000 FPO scheme, renewed focus on the aggregation of small, marginal and landless farmers to facilitate market linkages to enhance incomes and livelihoods. As a result, the number of registered Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs) has increased from 8,341 to 15,948 between 2019 and 2022, presenting a significant opportunity to transform agriculture marketing for smallholder farmers. A diverse group of actors, including government agencies, corporate social responsibility arms of private corporations, foundations, NGOs, and agri-business conglomerates have joined forces in the form of cluster-based business organizations (CBBOs) to catalyse FPC formation. The Bihar Rural Livelihoods Promotion Society (BRLPS), also known as JEEViKA, recognizes the transformative impact of FPCs on the lives of smallholder farmers and, supports the development of FPCs across Bihar. In partnership with MSC, JEEViKA works to enhance 26 FPCs’ capacities, including innovative and sustainable value chains, effective governance structures, and the empowerment of women farmers.

However, growth is not without its challenges. Despite efforts to foster the development of FPCs, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) concluded that 45% of FPCs older than seven years were moribund at the end of FY 2021-22. Some attribute this non-functionality to the typical high failure rate of small businesses, while others point to deeper design and operational issues. In this blog, we discuss key, yet overlooked, factors obstructing the growth and long-term viability of FPCs, and the solutions JEEViKA is using to address them.

Hiring technically knowledgeable staff: Agribusiness requires specialized skills and expertise to generate profitable transactions. Most FPCs start off as simple aggregators of commodities where margins tend to be low. For example, aggregator margins are in the range of 2-3% for non-perishable commodities such as grains and cereals. To ensure sustained profitability, FPC management need to manage and measure quality, understand the specific market for each quality grade, negotiate optimal rates for logistics and storage, manage working capital, and facilitate strong market connections for access to timely information. These skills are developed through years of experience.

However, CBBOs typically deploy their own staff, who come from a social development background, to manage newly established FPCs. These staff are competent in community mobilization but lack the necessary agri-business skills to run a profitable FPC. Under the 10,000 FPO scheme, the salary support provided by the government to CBBOs is up to INR 25,000 (USD 312.5) per month for 3 years, yet MSC has found that recruiting experienced candidates for this salary is not possible. Recognizing that knowledgeable and qualified candidates require a higher salary, JEEViKA has made the strategic decision to hire individuals with agri-business backgrounds to act as CEOs of its FPCs and offers them market compensation. While policymakers need to rethink the support provided to FPCs, CBBOs also have to be resourceful to meet the gap.

Multiple business lines and multiple commodities: Many FPCs are formed as single commodity companies, influenced by the success of dairy FPCs promoted by the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB). As a single commodity company, the FPC is tied to the production and sale of one commodity. However, our experience shows that single agri-commodity FPCs struggle to thrive if they just aggregate and trade. While single-commodity FPCs do succeed, particularly those that undertake secondary processing and achieve substantial volumes, they require significant capital investment and specialized skills, such as food technology and processing for which many FPCs lack the resources.

The majority of small-scale farmers are involved in two or three cropping cycles annually, known as kharif (sowing post-monsoon), rabi (sowing in winter), and zaid (sowing in summer) and as a result, would be better served by FPCs that cater to the many commodities grown in the region, while providing the necessary inputs for each cropping season. Diversifying into multiple commodities offers several benefits including better staff utilization and productivity, effective use and rotation of working capital, increased resilience against commodity price fluctuations, and more active involvement of its members.

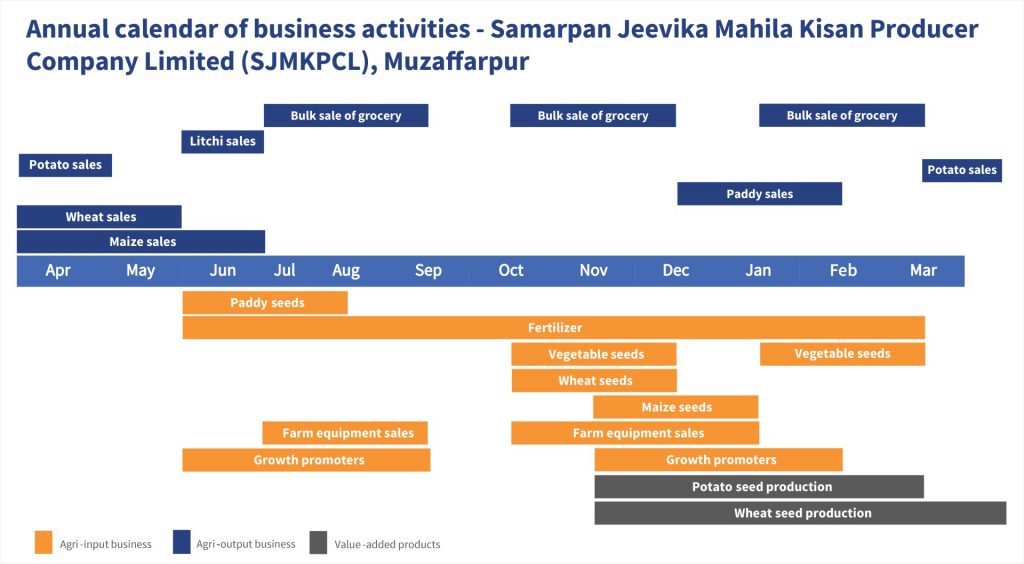

The transition to multiple business lines by the FPCs supported by Jeevika has proven successful. A prime example is Samarpan JEEViKA Mahila Kisan Producer Company Limited (SJMKPCL), which operates in three distinct business areas: agri-outputs, agri-inputs, and other businesses. The agri-outputs line includes commodities like paddy, wheat, litchi, and potato. The agri-inputs line covers a range of products like seeds, fertilizers, growth promoters, and farm equipment. The other business line includes seed production and bulk purchase of food and groceries for women members. With this diverse range of business lines, SJMKPCL has achieved profitability for the past two years. The figure below illustrates Samarpan FPC’s different business lines throughout the financial year.

Social capital in the local communities: The success of FPCs, in part, lies in the active involvement of its members. Developing the necessary social capital among the community can be a time-consuming process, but CBBOs with a history of impactful social and economic development initiatives have a head start over those starting their operations anew. For example, JEEViKA, with over 15 years of experience in livelihood promotion, financial linkages, and women’s economic empowerment, is well-positioned to mobilize members, establish strong leadership, and educate communities about the benefits of FPCs. Building this social capital among its members helps FPCs overcome the influence of middlemen and other intermediaries who have built their own social capital over time.

Financial support from inception to maturity: One of the critical roadblocks for FPO growth is working capital. Both trading in agri-commodities and agri-inputs require working capital to maximize business opportunities. Commercial banks and mainstream non-bank finance companies (NBFCs) depend on robust balance sheets and track records as part of the underwriting process, while the majority of FPCs are nascent or early stage and may not have the required net worth to obtain the requisite credit.

Most FPCs are also poorly capitalized despite special credit guarantee schemes and the equity grant scheme of SFAC. Only 11.2% of FPCs registered at the end of FY 21 across India have paid in capital equal to or more than INR 1 million (USD 12,500). Between FY 2015 to FY 2022, only 839 FPCs had access to equity grant from SFAC, while only 282 FPCs were sanctioned credit guarantees. JEEViKA provides working capital grants to newly formed FPCs in the early years to meet their liquidity needs, thereby enabling them to grow their businesses without the need for commercial capital. JEEViKA’s ability to raise funds is not easy to replicate for most CBBOs and there is a genuine need for philanthropic capital to provide critical seed money for FPCs to meet the financing gap in the initial 2-3 years. The government/policymakers could also help by expanding coverage of the equity grant and credit guarantee schemes, increasing upper limits for good-performing FPCs, and encouraging commercial banks to enter the FPC lending market.

Simplifying the business environment for FPCs: Despite efforts to promote FPCs in India, many face difficulties obtaining basic business licenses, particularly to sell agriculture inputs such as fertilizers, because local government officials have discretion to issue these licenses. FPCs often lack the knowledge and networks to secure them. The state governments can ease the licensing process by creating a common agri-inputs license (seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides) for FPCs.

Additionally, there are numerous regulatory compliance requirements to which FPCs must adhere, such as filing Goods and Services Taxes (GST) and Income Tax (IT) returns, conducting annual audits, and holding Annual General Meetings (AGMs). Non-compliance could result in fines and legal consequences. To mitigate these challenges, JEEViKA provides professional support to manage the compliance of its FPCs and concurrently trains their managers on the necessary requirements, ensuring they stay up-to-date and avoid missing regulatory deadlines.

This is another area where philanthropic organizations could support the growth of FPCs through investments in the training of auditors and building the capacity of FPC managers in areas of regulatory compliance, business licenses, etc. This approach mirrors the large-scale efforts put into training of microfinance institutions from two decades ago.

Responding to the constraints above has fueled a robust growth trajectory for JEEViKA FPCs. Over the last three years, total business revenue of the FPCs experienced growth of more than 353% as they continue to progress towards financial profitability.

FPCs are powerful tools to allow smallholder farmers to have more control over the markets in which they trade. FPCs can channel high-quality services like access to inputs, credible buyers, advisory, etc. to transform agriculture productivity and increase the incomes of small-scale producers. However, CBBOs should recognize the inherent challenges that FPCs face and learn from the likes of JEEViKA, which has addressed the pitfalls associated with managing FPCs, helped them deploy the right business models, acquire the right talent and arrange for necessary and adequate financing to ensure the FPCs’ potential is realized.