In 2001, Rama and his family packed their meager possessions from their home in the Eastern Indian state of Bihar. They were on their way to the capital of Delhi, where Rama had found a job as a security guard. Yet they struggled with household expenses when they landed up in the capital city. Despite having a ration card under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), the family had to wait for many years to receive their ration entitlement from Delhi, since their ration card was issued in Bihar.

Till June 2022, Rama’s family had to spend a substantial portion of their income to make several long and expensive trips back to their village in Bihar every three months to avail of their rations. Moreover, they were worried their ration card would become invalid if it became dormant due to lack of use.

However, the One Nation One Ration Card (ONORC) program’s implementation changed their fate for the better, as it permits beneficiaries to obtain their rations from any fair price shop (FPS) across the country. In May 2022, a neighborhood dealer informed them that they could receive their rations in Delhi, thanks to the portability facility under the ONORC. Since then, they have successfully availed of their monthly ration in Delhi. Rama and his family no longer need to dedicate time and resources to visit their village or pay out of pocket for rations.

Rama’s story rings true for more than 330,000 interstate migrant NFSA beneficiaries who avail of their monthly ration entitlements from states other than their home.[1] These beneficiaries represent a minuscule percentage of interstate migrants in the country. As per the 2011 census, India has approximately 450 million internal migrants. While all these migrants do not need interstate portability services, a nationally representative study by MSC on ONORC pegs the potential for interstate portability transactions at 5 to 5.5 million per month.[2] Hence, the ONORC program is yet to achieve its objective of providing access to food, particularly to interstate migrant populations.

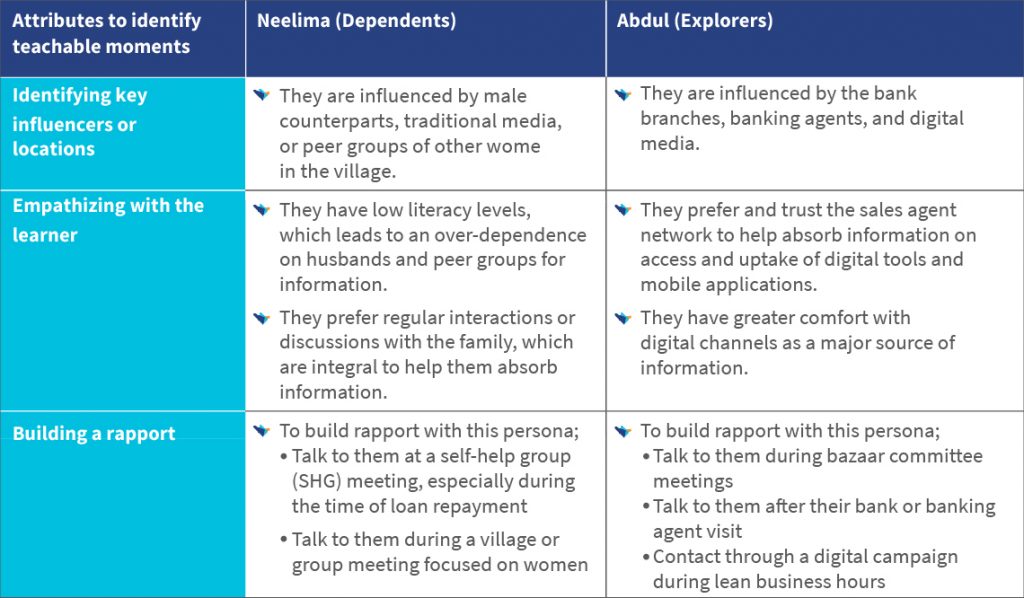

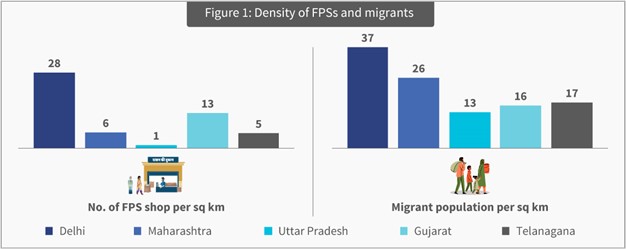

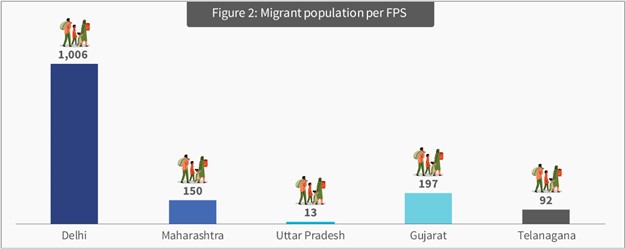

Delhi accounts for approximately 70% of the 330,000 interstate portability transactions. Indian states with larger migrant populations, such as Maharashtra and Gujarat, account for only 9% of interstate portability transactions. An FPS in Delhi conducts approximately 113 portability transactions per month compared to less than one in Maharashtra and Gujarat. Even comparable urban centers, such as Mumbai and Surat, which attract large migrant populations conduct only five and three transactions per FPS per month, respectively.[3] Despite a smaller migration population, Delhi ranks at the top with the most portability transactions conducted at FPSs.

So, what works well for Delhi?

In January 2023, MSC conducted qualitative research to identify reasons behind the wide variation in the uptake of interstate portability transactions among Indian states.[4] We analyzed three major aspects of ONORC, including stakeholder awareness, supply-side inclination, and system readiness—primarily the supply chain—to determine why Delhi had the most interstate portability transactions.

- Many FPSs, coupled with a dense migrant population, helped build awareness through word of mouth

Delhi has the highest number of FPSs and migrant population per sq km than other states, so awareness of interstate portability is higher (see Figure 1). Moreover, Delhi has the highest migrant population per FPS at 1,006 migrants per FPS compared to 150 for Maharashtra (see Figure 2). Although Mumbai has the highest migrant population among the major urban centers, it has only 575 migrants per FPS. The low density of migrants per FPS significantly reduces the propensity for solid word-of-mouth channels and, therefore, high awareness of portability. Most survey respondents were aware of ONORC. In Delhi, nearly every beneficiary was aware.

Beneficiaries across other states mentioned that many FPSs lack the ONORC program’s information, education, and communication (IEC) material. Any available IEC material is in the local language, which challenges migrants from other states who may not know it. Beneficiaries also mentioned that the IEC material lacks information on ONORC’s specific aspects. These aspects include interstate portability, the possibility of partial rations in both the home and destination states, and the ability to pick up the ration using the Aadhaar or ration card number for identification and authentication purposes rather than the physical ration card itself.

- Supply-side stakeholders create an enabling ecosystem

The government officials of the Civil Supplies Department of Delhi organized in-depth briefing sessions with FPS dealers to create local networks to circulate information among beneficiaries. FPS dealers in Delhi mentioned they had created WhatsApp groups on ration availability. FPS dealers in Thane also reported adopting the same approach, which may contribute significantly to the fact that Thane accounts for the highest number of interstate portability transactions in Maharashtra.

- System readiness, particularly in the supply chain, enhances efficient delivery

In all states except Telangana, FPS dealers reported a lack of provision for restocking once they had distributed the allotted quantity to beneficiaries. As a result, these FPS dealers had to deny rations to both home state and migrant beneficiaries who arrived in the later days of the cycle. However, in Delhi, the officials allow FPS dealers to request stock from nearby FPSs if additional rations are needed for distribution to migrant and home state beneficiaries. As a result, migrants in Delhi are not denied rations no matter at what point in the cycle they come for their rations.

Way forward

In light of the enabling factors uncovered in Delhi during our field research, MSC recommends a more targeted communication strategy to improve interstate portability transactions under ONORC in other states. This could take the form of a mixed communication strategy focused on beneficiaries, FPS dealers, and district-level officials. A high level of beneficiary awareness is among the major reasons why the uptake of interstate portability transactions worked well in Delhi.

For beneficiaries, targeted awareness campaigns should be promoted through the Prime Minister’s “Mann ki Baat” program to create awareness of ONORC and ensure large-scale impact. Further, the identification of migrant pockets to target bilingual communications and local-level awareness drives, such as announcements at railway and bus stations, will help strengthen word-of-mouth channels. These campaigns should emphasize specifics of portability, such as interstate and intrastate portability, partial rations, rations distributed through the Aadhaar or ration card number, and other salient features to facilitate successful interstate transactions.

States should replicate the IEC sessions conducted in Delhi to enhance stakeholder readiness on the supply side and sensitize district officials. In turn, these officials will then further the discourse with FPS dealers. These sessions should include information on the program’s salient features, portability, and the importance of creating local networks for communication. Dealers should also learn that denying rations to beneficiaries is not encouraged. Instead, they should engage with district officials to resolve system-related challenges or refer beneficiaries to neighboring FPS outlets.

Additional recommendations to ensure the ONORC program’s full use include a provision for FPS dealers to restock rations or the ability to request extra rations, as seen in Telangana, through the electronic point-of-sale devices (e-PoS) devices to make delivery more efficient for dealers. Coordination between states on ration delivery, equal treatment of beneficiaries, and resolution of IT challenges will help improve the ONORC program’s uptake, particularly interstate portability transactions

ONORC is an ambitious government program that strives to ensure food security for millions of migrants nationwide. However, four years after implementation, ONORC has some more road top cover before it can achieve its stated objective of providing migrant populations unfettered access to food rations. Inhibiting factors include low awareness on the demand side and lack of readiness on the supply side.

State governments can follow the above-suggested measures if they intend to play an integral role to ensure millions of migrants, much like Rama and his family, can reap the ONORC program’s benefits through information that is accurate, relevant, timely, and accessible.

[1] Portability transactions that occur in a state other than the home states of the beneficiaries are interstate transactions. The portability transactions that occur within the same (home) state but in an FPS other than to which the beneficiary is tagged are intrastate.

[2] MSC conducted a nationally representative study to assess ONORC’s implementation. We covered an overall sample of 5,735 citizens across 19 states.

[3] Mumbai and Surat have 2,905 and 816 FPSs, respectively.

[4] We conducted the research in five states namely Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Telangana, and Uttar Pradesh