The landscape of CICO agents in Indonesia is transforming rapidly. MSC conducted a study to understand the world of these agents through our innovative diaries research methodology. The study engaged diverse financial agents across Indonesia’s dynamic landscape, such as banking, G2P, and FinTech agents. The study delved into various dimensions, including agency profitability, gender dynamics, and challenges these CICO agents faced. From the research insights, we created recommendations on various prospective use cases for agents to make their income less volatile and businesses sustainable.

Crisis, resilience, and adaptation: farming and financial services in times of climate change

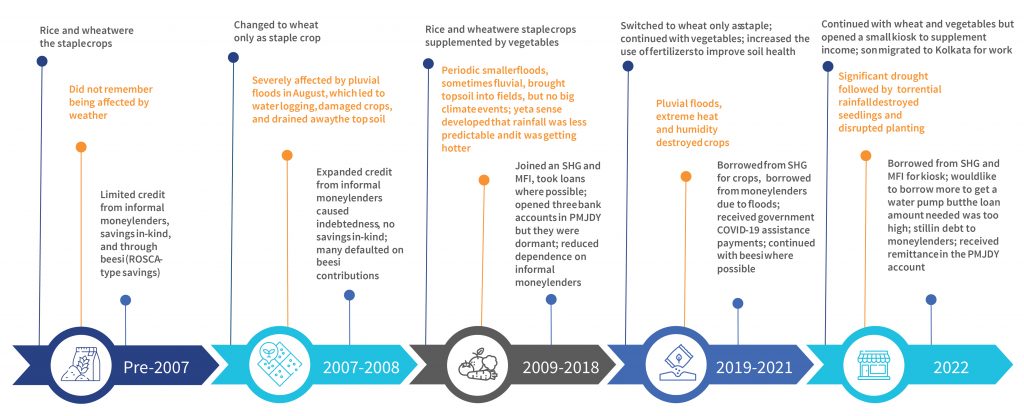

“I have lived through a lot. Sometimes too much,” says Krishna Lal wistfully.[1] He remembers his youth and early adulthood fondly as a time when life in the village was simple and his family usually had enough food on the table. In those days, the village was far away from bank branches, and anyway Krishna Lal and his family considered themselves “too poor for banks.” Instead, when they had emergencies, which usually arose when they needed doctors or medicines, they would borrow from local moneylenders.

Each year after the harvest, the family stored about half of the harvested crops—primarily rice in those days—to meet their consumption needs. They would sell the rest and invest the money in livestock, although they also hid away some money in clay pots around the household. Krishna Lal’s wife, Devi, saved small amounts through her beesi, a savings club that pays out to one of its members each monthly round. She would usually use the proceeds to buy household utensils. She also squirreled away small amounts without Krishna Lal’s knowledge—and used these secret funds to buy treats for her son, Abhishek, and daughter, Preeti.

Each year after the harvest, the family stored about half of the harvested crops—primarily rice in those days—to meet their consumption needs. They would sell the rest and invest the money in livestock, although they also hid away some money in clay pots around the household. Krishna Lal’s wife, Devi, saved small amounts through her beesi, a savings club that pays out to one of its members each monthly round. She would usually use the proceeds to buy household utensils. She also squirreled away small amounts without Krishna Lal’s knowledge—and used these secret funds to buy treats for her son, Abhishek, and daughter, Preeti.

This tranquil life changed in 2007 when the worst floods “in living memory” washed through the village, sweeping all they had before them. The rainfall in July was five times higher than the monthly average. By August, the entire village was underwater. These largely pluvial floods waterlogged the fields, destroyed the rice crops, and remained for many months.

Fortunately, Krishna Lal had good relations with the moneylenders, and so he could borrow several times to keep food on the family’s table. Yet, with the loss of the rice crops, Krishna Lal could not save any grain and had to keep borrowing. On some days, the family ate only one meal. Devi’s beesi saw many participants stop their monthly contributions. It took years and significant changes in membership to rebuild the trust.

In the period from 2009 until 2019, life in the village returned to normal and grew increasingly sophisticated. With improved roads to the market, farmers, including Krishna Lal began to grow a range of vegetables alongside these staples. Krishna Lal found okra particularly lucrative. Some small-scale floods occurred in this decade—most notably in 2019, but nothing of the scale seen in 2007-2008. However, all the villagers noted that the monsoon was less and less predictable, and that the summers were hotter than they remembered from earlier times.

It was in this period that Krishna Lal encouraged Devi to join a self-help group formed by a local NGO to save and sometimes even borrow to help manage the household finances. This helped reduce their dependence on local moneylenders. She found the meetings and the bookkeeping a chore, but when the group got access to bank-linkage loans, Devi could borrow to buy fertilizer and a TV. Krishna also increased the dosage of fertilizer as he was not getting the yield as before. These fertilizers he usually bought at a premium of almost 30-40% over the MRP due to short supply from local retailers.

In 2017, after many attempts, Krishna Lal managed to open a bank account under the government’s Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) financial inclusion program. But the accounts were largely dormant as all the transactions happened in cash. The government’s zealous drive to ensure every adult in India had an account meant that bank staff and banking correspondents (agents) were heavily incentivized to open accounts, whether people needed them or not—so soon Krishna Lal had another PMJDY account, and Devi had one too. But since neither Krishna Lal nor Devi could get employment under the MGNREGA program, their accounts remained dormant from the moment the accounts were opened. Devi continued with her beesi, primarily for its social function—she enjoyed the chance to sit around and exchange village gossip with her friends from time to time.

In 2019 and 2021, the floods returned—with a vengeance—and Krishna Lal found out that he was not as resilient as he had believed. During these floods, he stopped growing rice and was focusing on wheat, which could be planted once flood waters recede in September or October and commanded higher prices in the market. But he started to worry about how much fertilizer he had to use to maintain output levels. He was also worried by the weather. May to July was unbearably hot and rains evaded their village until the end of July—he was unsure when to plant his rice seeds. Then it rained in a way he had never seen before. Within days, floods were rolling through his fields and then the village itself once again. It was like 2007 or worse. He was back to borrowing from moneylenders to keep food on the family table. Furthermore, the increased heat and humidity meant that his vegetables were infested with pests. Farming was no longer enough to finance his family’s needs—they had to think of ways to earn more.

In 2019 and 2021, the floods returned—with a vengeance—and Krishna Lal found out that he was not as resilient as he had believed. During these floods, he stopped growing rice and was focusing on wheat, which could be planted once flood waters recede in September or October and commanded higher prices in the market. But he started to worry about how much fertilizer he had to use to maintain output levels. He was also worried by the weather. May to July was unbearably hot and rains evaded their village until the end of July—he was unsure when to plant his rice seeds. Then it rained in a way he had never seen before. Within days, floods were rolling through his fields and then the village itself once again. It was like 2007 or worse. He was back to borrowing from moneylenders to keep food on the family table. Furthermore, the increased heat and humidity meant that his vegetables were infested with pests. Farming was no longer enough to finance his family’s needs—they had to think of ways to earn more.

Of course, 2020 was also the year that the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Finally, Devi’s PMJDY account proved useful—after she reactivated it, a process that took multiple trips to the bank branch. Soon, she received four payments of INR 500 (USD 6.67) each from the Government of India.

In 2022, the pressing need to find another source of income emboldened Devi to borrow both from her SHG and a microfinance institution she had recently joined. With the INR 9,000 (USD 120), she could stock a small kiosk in a kutcha lean-to that Krishna Lal built adjoining their house. Furthermore, her son Abhishek went to Kolkata where he found work as a day laborer at a construction site. When he could send money back to his parents, they started to withdraw the cash from an ATM outside the bank branch in the market town eight kilometers away using the RuPay card attached to their PMJDY account.

However, despite the small earnings from the kiosk and Abhishek’s intermittent remittances, the family still struggled to make ends meet. Krishna Lal had for many years dreamed of buying a water pump to irrigate his fields in times of drought and thus increase his yields. While the opportunity, and need, for this climate adaptation were stark, no one would lend him the large sum money he needed for this crucial piece of equipment. In 2022, he could really have used the pump as a merciless drought ravaged his crops from April to July. The heat was unbearable and the land was parched—it was useless to plant anything. And when the rains came in August, they were torrential…

However, despite the small earnings from the kiosk and Abhishek’s intermittent remittances, the family still struggled to make ends meet. Krishna Lal had for many years dreamed of buying a water pump to irrigate his fields in times of drought and thus increase his yields. While the opportunity, and need, for this climate adaptation were stark, no one would lend him the large sum money he needed for this crucial piece of equipment. In 2022, he could really have used the pump as a merciless drought ravaged his crops from April to July. The heat was unbearable and the land was parched—it was useless to plant anything. And when the rains came in August, they were torrential…

“Farming has become such a lottery now that the weather gods are no longer our friends. Everyone in the village has sent their sons away to earn in the city—we have no other way to make ends meet”, sighs Krishna Lal. “Everything has changed.”

If we are to enable farmers like Krishna Lal to respond to the growing climate crisis, we will need to revolutionize financial services for agriculture to support both climate resilience and adaptation. The CIFAR Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRAg) working group has outlined what this will take and the central role that digital technology must play in this.

The Crag Virtual Club brings together innovative startups that work in climate-smart and climate-resilient agriculture alongside investors, international donor organizations, financial services providers, and implementation agencies. It enables the exchange of ideas to ultimately identify and upscale promising business models to strengthen climate resilience and adaptation for countless smallholder farmers, much like Krishna Lal. Join us!

[1] Krishna Lal is a composite archetype farmer derived from MSC’s extensive work in UP and Bihar on agriculture and climate change—his story is indicative.

The climate crisis is not gender neutral – women’s voices must be heard

Source: (Randall, n.d.)

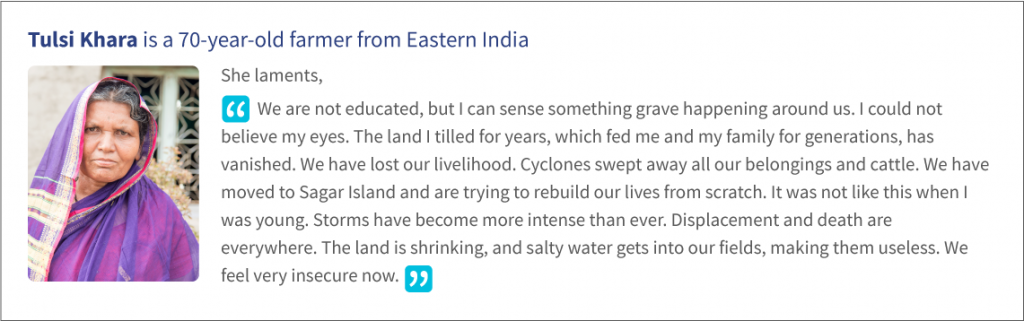

Women who grapple with poverty commonly face higher risks and more significants burdens from climate change’s impact. Climate change has multifaceted effects on women’s lives, which range from socioeconomic, cultural, behavioral, and health issues. Women’s unequal participation in decision-making processes and labor markets often prevents them from fully contributing to climate-related planning, policymaking, and implementation. The limited availability of gender-segregated data restricts in-depth assessments of climate change’s gender dimension.

With the increased data availability, a clear correlation arises between gender inequality and vulnerability to climate change. As per Tshakert et al. (2019), social and cultural factors help identify and anticipate future risks. Gender inequality leads to more biophysical and social vulnerability and lesser adaptive capacity in women than men (UNEP, 2023). Furthermore, the stakes go beyond the boundaries of economics or health when climate change is researched from a gender perspective.

We need to understand the gendered impacts of climate change to create a holistic understanding of its threats and measures to mitigate it.

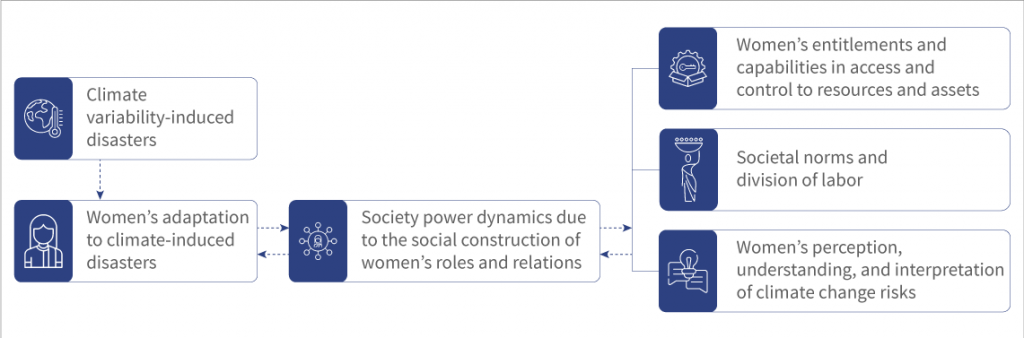

This framework (Figure 1) is adapted from Yiridomoh Y. Gordon et al. (2019)—a study conducted on small-scale women farmers in Ghana to understand the adaptation to climate change and its derivatives. It observed that female farmers’ vulnerability to climate variability is rooted in gender-based cultural norms, household responsibilities, inaccessibility to assets and resources, and lack of information and suitable technology.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework that links women, climate variability, and adaptation

Source: Yiridomoh Y. Gordon et al. (2019)

Climate change’s gender impact also leads to other social implications for women:

- Increase in women’s unpaid labor: Women face emotional stress and increased unpaid household work due to climate change, revealed an MSC study conducted on climate resilience among smallholder farmers in India. One respondent in the study noted, “Floods make the fuelwood and biomass soggy. It increases the cooking time substantially.” (MSC, 2023). Another often-cited case study comes from the “water wives of Maharashtra” of Denganmal village, 185 km from India’s financial capital, Mumbai (Blakemore, 2015). The village faces continuous droughts in summer and lacks water pipelines. The men of the village, who are predominantly farmers, marry more women to take care of the family’s water requirements. These women are typically from families that cannot afford a dowry[1] or widows who seek to regain their social status.

- The increased toll of disasters: Girls in Bangladesh reported a rise in household work after a flood. They had to walk long distances to fetch water, clean their houses after a flood, and take leave from school to look after their homes. After disasters, families often employ girls in domestic service, agriculture, and textile factories, while boys mostly remain in school.

For instance, after Cyclone Sidr struck Bangladesh in 2007, people reported that many girls moved to urban areas to work in garment factories or engage in domestic work. Jhumu is an 18-year-old girl from Barguna, Bangladesh. She said, “Girls also work as domestic help with rich local families. Their families find it easier to stop their education—which is not the same with boys. Families want to continue their education.” (Swarup et al., 2011).

- Increase in child marriages and subsequent violence: Research has established that climate change and other environmental crises multiply the drivers of child marriages, such as poverty, displacement, conflict, and loss of education. This subsequently puts young girls at grave risk of domestic and sexual violence, which hurts their physical and mental health. Studies (UNICEF, 2017; Barnfonden, 2021) have also shown links between droughts, floods, and increased child marriages.

Women’s voices need an audience and action.

Atela et al. (2018) argue that low education levels and structural exclusion from land, capital, markets, and new technologies limit women entrepreneurs in Kenya’s semi-arid lands (SALs) to limited livelihood activities and expose them to climate risks. These factors also determine how well women can build resilience and hinder their agency in decision-making. The underrepresentation of women hinders climate-responsive planning, policymaking, and implementation. Women entrepreneurs’ voices, aspirations, and capabilities must find clear articulation in public policy, legislative, and investment domains.

Research has shown that women entrepreneurs know livelihood needs, assets, opportunities, and stressors, which enable them to design and operate MSMEs that respond to households’ livelihood and adaptation needs (Horrell & Krishnan, 2007). Female-led MSMEs remain underutilized at the societal level in developing adaptation and resilience strategies.

As per the available data (FAO, 2011; UNFCCC, 2023), “if rural women had equal access to agricultural resources as men, yields could increase by 20–30%, and the overall number of hungry people worldwide could be reduced by 12-17%.” Women are also the first responders to any climate change disaster, especially with their increased role as caregivers at household-level behavioral changes and planning. They contribute to recovery after a climate change event as they meet the early recovery needs of their families and strengthen community building. However, we should not place the entire responsibility of responding to climate change on women, the “feminization of responsibility,” as also discussed by Wright, G. (2023).

In this respect, we can mitigate or adapt to climate change impacts through women’s involvement in community-level planning. We can build stronger, more resilient communities that are better equipped to face climate change’s challenges. Women’s empowerment may lead to better climate solutions. Policymakers and development practitioners must engage both male and female farmers to confront climate vulnerability and enhance their capacity to cope with climatic stresses for any farm-level adaptation.

[1] A dowry is a custom practiced in South Asia where a gift of substantial monetary value is given from the bride’s family to the groom upon marriage. The practice is prohibited in India as per the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961, yet continues to be practiced widely.

The role of capital in unlocking growth for MSEs through group-based informal financial services in Africa

MicroSave Consulting (MSC) is a boutique consulting firm that has, for 25 years, pushed the world towards meaningful financial, social, and economic inclusion. These podcast series are hosted by MSC for dedicated founders, start-ups, investors, and other stakeholders in the startup ecosystem. Through this bouquet of curated conversations around developments in the financial inclusion space, we offer insights and lessons based on our research and expertise.

In this podcast, financial inclusion expert at MSC Kim Kariuki is joined by Sybil Chidiac of The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Grace Majara of CARE USA, and Phyllis Kariuki of the World Food Programme.

They each share their thoughts on access to group-based informal financial services and their usage.

Cash-in and cash-out (CICO) agent use cases: Opportunities for diversification

In developing countries, such as India, Kenya, Bangladesh, and Indonesia, cash-in and cash-out (CICO) agents encounter sustainability challenges. These challenges arise from stiff competition, reduced commissions, and low margins from user-initiated digital financial service (DFS) transactions. MSC recommends several solutions to foster agent sustainability. These include evaluation of agent willingness, mobility, technical and soft skills, digital savviness, financial sustainability, ability to identify potential customers, and ecosystem support during the selection of use cases. The implementation of these use cases will help providers drive the financial sustainability of agents and, consequently, promote financial inclusion among low- and middle-income customers.

Smallholder farmers worldwide are on a perilous journey amid climate change—where are they headed?

“I have never seen such heatwaves in April in Mastung, nor such massive floods in my lifetime. It rained continuously for more than 120 hours in some areas. This much water seems unreal. It has washed away all we had.” (Baloch & Taylor, 2022)

I. Introduction

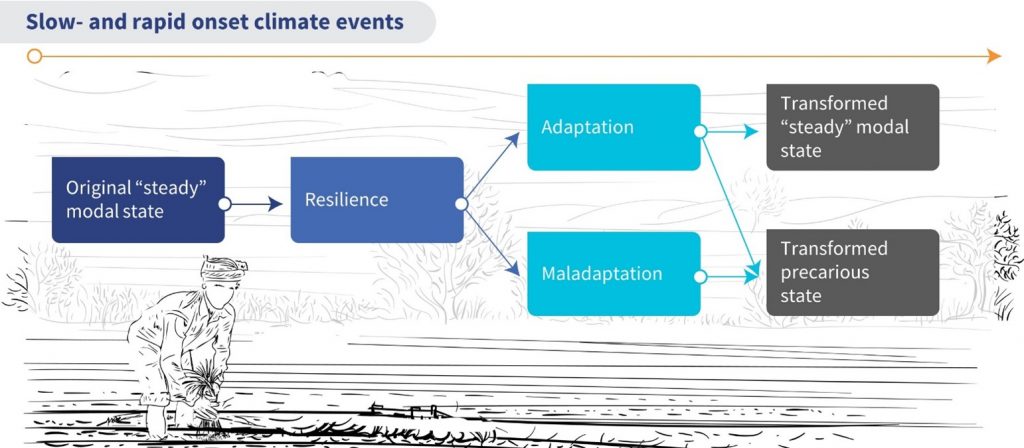

The literature on climate change typically differentiates between slow- and rapid-onset climate events. But climate change events have become progressively more regular and extreme, so the distinction is increasingly irrelevant. Smallholder farmers worldwide bear the brunt of these changes, often facing drought and excess rainfall within a single season. MSC’s work on climate change’s impact on agriculture in Bangladesh, India, and across Africa highlights how farmers’ incomes and assets are being eroded.

If we expect to contribute meaningfully to mitigate this global trend, we must understand the challenges facing smallholder farmers. We must explore the pressures smallholder farmers struggle with and their perilous journeys to build resilience, adapt, and transform their livelihoods.

II. Original “steady” modal state

“We have experienced drought before, but now it is happening almost every year. In the past, we at least had some grain stored from better yield years and got by with it. But these past few years, the yield has been consistently poor. I do not know how we are going to survive the coming winter.” (Onta & Resurreccion, 2011).

Smallholder farmers have nurtured land, crops, and livestock for millennia to earn a living. Those who have small parcels of land and who can invest in agricultural production could make ends meet. These farmers managed the somewhat unpredictable and interlinked cycles with indigenous knowledge and experience. They could usually tide over seasons when pests or diseases attacked, or the weather was unkind. They provide a third of the world’s food. Yet 40% of these farmers continue to live on less than USD 2 a day.

However, as climate change distorts and amplifies weather patterns, smallholder farmers’ ability to manage is increasingly under threat as the deviations from the mode increase. In response, farmers have to build resilience, adapt or transform. Their journey is underway.

For this blog, we adapt LSE’s 2022 definition of resilience. LSE defines resilience as the capacity to prepare for, respond to, and recover from stresses, shocks, and lifecycle events, including hazardous climatic impacts, while minimizing damage to household consumption, societal well-being, the economy, and the environment. IPCC, 2019

However, in 2014 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defined “incremental adaptation” as “actions where the central aim is to maintain the essence and integrity of the existing technological, institutional, governance, and value systems, such as through adjustments to cropping systems via new varieties, changing planting times, or using more efficient irrigation”. They contrasted this with “transformative adaptation”, an approach that “seeks to change the fundamental attributes of systems in response to actual or expected climate change and its effects, often at a scale and ambition greater than incremental activities”. So we might see IPCC’s incremental adaptation as resilience.

esilience tends to be more reactive, while adaptation is more proactive and anticipatory, as it involves planning and preparing for future climate impacts. That said, drawing a clear distinction between resilience and adaptation—and, indeed, development—is difficult. Many approaches to enhancing resilience can be and often are implemented as adaptation measures, as we will see in the discussion below. And as McGray et al. of the World Resources Institute noted in 2007, “Rarely do adaptation efforts entail activities not found in the development “toolbox.””

“Adaptation is sometimes seen as being part of resilience. Resilience capacity is described as a combination of: (i) shock absorbing and coping; (ii) evolving and adapting; and (iii) transforming. By this definition, coping is the first and ideal strategy for managing risk. However, when societies exceed their ability to cope, they should be able to adapt to the adverse changes they face” – LSE, 2022.

III. Resilience

Technologies to help farmers enhance their resilience are widely available. These include flood- and drought-resistant seeds, water, and soil conservation techniques, agro-forestry, community-based collaboration, climate information services, and several financial services, including weather-based insurance. In many countries already impacted by climate change, a growing number of farmers are using these approaches to begin to adapt and build resilience.

IV. Adaptation

“Estimated adaptation costs in developing countries could reach $300 billion every year by 2030. Right now, only 21 per cent of climate finance provided by wealthier countries to assist developing nations goes towards adaptation and resilience, about $16.8 billion a year.” – United Nations (accessed April 2023)

Adaptation involves smallholder farmers making significant adjustments to their farming practices and livelihood strategies. Many are similar to, and/or are extensions of the resilience strategies described above. Others require more extensive changes, such as building shelters for livestock to protect them from the sun and excess heat, raising housing and seedling or vegetable beds above flood water levels, or changing from rice to shrimp production in the face of the salination of soil. These require substantially more capital investment than most measures to enhance resilience, and few financial service providers are willing to offer the loan sizes and tenors needed for adaptation. Other examples of adaptation include diversifying income sources to include non-farm activities and the temporary or permanent migration of family members.

However, as farmers make these substantial changes, they also risk maladaptation. They often end up prioritizing short-term gains and quick-fix solutions. Such misplaced priorities can lead to increased vulnerability and reduced adaptive capacity in the face of evolving climate risks.

V. Maladaptation

“Most of our youth and able-bodied men migrate to the south to look for employment opportunities. Many do not return at the start of the farming season, which affects the availability of farm labor. In turn, the unavailability of labor affects farm operations and crop yield, which has implications for food security in this community.” (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2022).

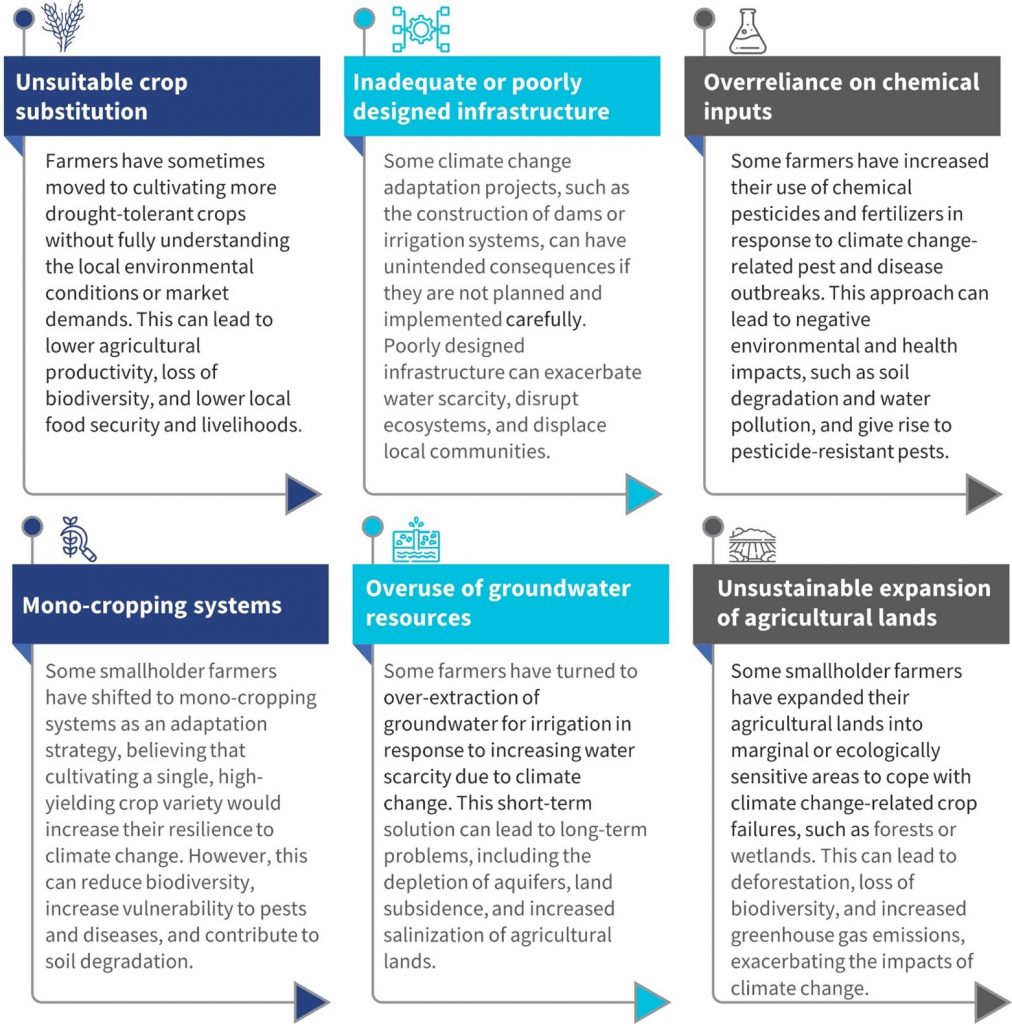

Maladaptation implies actions or strategies that may inadvertently increase vulnerability to climate change or undermine a farming system’s long-term sustainability. MSC has seen common examples in its work, which include the overuse of fertilizers and pesticides in response to declining soil health or climate change-induced crop diseases. The diagram below outlines other common maladaptation practices.

VI. Positive “steady” modal state transformation

In an ideal world, adaptation should lead to a sustainable steady, modal-state transformation. Such transformation would provide smallholder farmers with long-term climate resilience, enable them to manage the vagaries of the weather, earn an improved and reliable income, and thus secure the family’s livelihood and future. As co-convener of the CIFAR Alliance’s Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRAg) working group, MSC works with various players to identify and enhance digital technology’s role to transform agri-food systems across Africa and Asia. Yet for many farmers, this positive transformation is elusive—not least of all because the vagaries of the weather are increasingly extreme, and the “panarchy” cycles are becoming more unpredictable and unruly.

VII. Negative precarious state transformation

“We are here for three generations. How can we migrate, leaving our land, property, and generations-long memories?” (Ahmed et al., 2021)

The alternative, less positive outcome is where the smallholder farmer and their family are forced to abandon farming altogether, typically after a remorseless downward slope of income and asset depletion. They then often migrate to live in squalor in urban slums as a last resort (Kugelmann, 2020 and Chung, 2022).

VIII. Conclusion

A growing proportion of smallholder farmers are under immense pressure from climate change and being forced on a perilous journey as they try to build resilience, adapt or transform to manage climate events. This journey is not linear but fraught with challenges. However, we have the technologies to positively transform the agri-food systems within which smallholder farmers play such an important role. The challenge is how we can encourage and support farmers to adopt and use these technologies along their journey.