Decoding payment challenges in India’s government fund flow ecosystem

Between 2016 and 2023 the Government of India (GoI) increased its annual expenditure in the social sector by 134% from USD 108 billion (INR 9 lakh crore) to USD 253 billion (INR 21 lakh crore). However, higher budgetary allocations do not guarantee a high impact, as ample evidence shows that the budget remains unspent. Outcomes remain low even with the spent budget.

A major source of these deficiencies is the challenges in public finance management (PFM), especially those related to fund release and payment processing that continue to constrain government officials’ capacity to execute programs on the ground. The twin challenges of unspent funds and unpaid dues have plagued government payments in India. These payments include three types of payments, from the government to other government departments or tiers (G2G), government to businesses or contractors (G2B), and government to individuals or people (G2P). For instance, at least 56% of the USD 37 billion (INR 3.1 trillion) released toward centrally-sponsored schemes in FY 2023 remained unspent with the single nodal accounts (SNAs) of states to implement programs until March 2023. Moreover, unpaid dues by the government added up to almost USD 115 billion (INR 9.5 lakh crores) in various economic sectors in 2020.

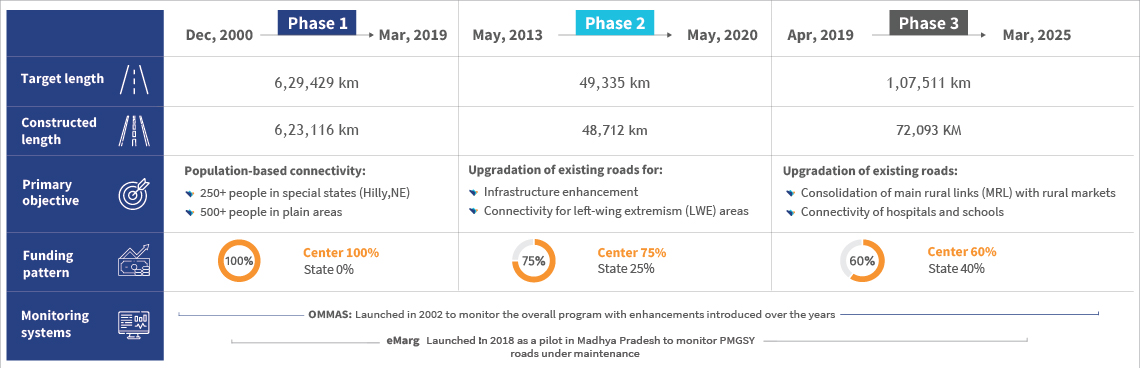

While India’s direct benefit transfer (DBT) system for fund transfer has gained global acclaim, a larger universe of centrally-sponsored and central sector schemes involve conditional government transfers. This means the transfers depend on the fulfillment of physical milestones. Simple examples include a payment made to a contractor on the completion of a section of rural road construction under the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) or payment to an empaneled health service provider against treatment under Ayushman Bharat or to Anganwadi workers for their services. Most schemes require a web of manual processes before payments from the consolidated fund of India (the primary government account for all revenue received by the government and expenses made by it) or the state (the similar account at the sub-national level) reach the beneficiaries—businesses in the case of G2B payments, and people in the case of G2P payments.

The program management system for most schemes faces process-related challenges, such as suboptimal workflow and outdated IT systems; people-related challenges, which include administrative burden and diffused accountability; and finance-related challenges around the flow of funds contingent on multiple layers of approval. High budgetary allocations may not necessarily translate into on-ground impact unless these key constraints related to fund release and payment processing are addressed. These challenges are not unique to Indian government stakeholders but are faced by governments across the world.

Digital revolution in India’s PFM landscape

The Indian government has deployed digital technologies to keep pace with the increasing volume and value of their payments at the center and in the states. The public financial management system (PFMS) has been at the core of the center’s efforts. It has evolved from its humble beginning in 2009 when it tracked funds released under all programs sanctioned by the GoI. Today, it has grown into a centralized transaction system and platform that provides end-to-end financial management services to all stakeholders. Similarly, most states use their respective versions of integrated financial management information systems (IFMIS) combined with the PFMS.

Progressive reforms in the PFM have ensured a gradual shift from a prescriptive fund release system to a more demand-driven fund release system. These reforms include the deployment of Single Nodal Agency (SNA) and, more recently, pull-based fund transfer systems, such as SNA-SPARSH for the centrally sponsored schemes (CSS). SNA reforms, launched in 2021, have reduced the float in the system- CSS funds sit in just around 3,300 bank accounts as opposed to around 1.8 million earlier, and led to better cash management. Moreover, the SNA dashboard has improved the observability and monitoring of funds. Recently, India’s Finance Minister also spoke in the parliament about the SNA reform and claimed that it led to an estimated savings of USD 1.2 billion annually.

However, the float is yet to be eliminated. Also, the funds are still being ‘pushed’ in advance, albeit with fewer intermediate halts, at shorter spurts, and with a good view of where it is at any given time. The gap between the fiscal and physical events has also reduced, but not entirely eliminated. This blog discusses the smart payments ecosystem that endeavors to move government payments to a “just-in-time” release. This means smart payments will pull funds from the Consolidated Fund of India (CFI) and pass them on directly to the beneficiary’s bank account in real time when payment for the work is due.

Smart payments to solve challenges in payment processes and fund disbursement

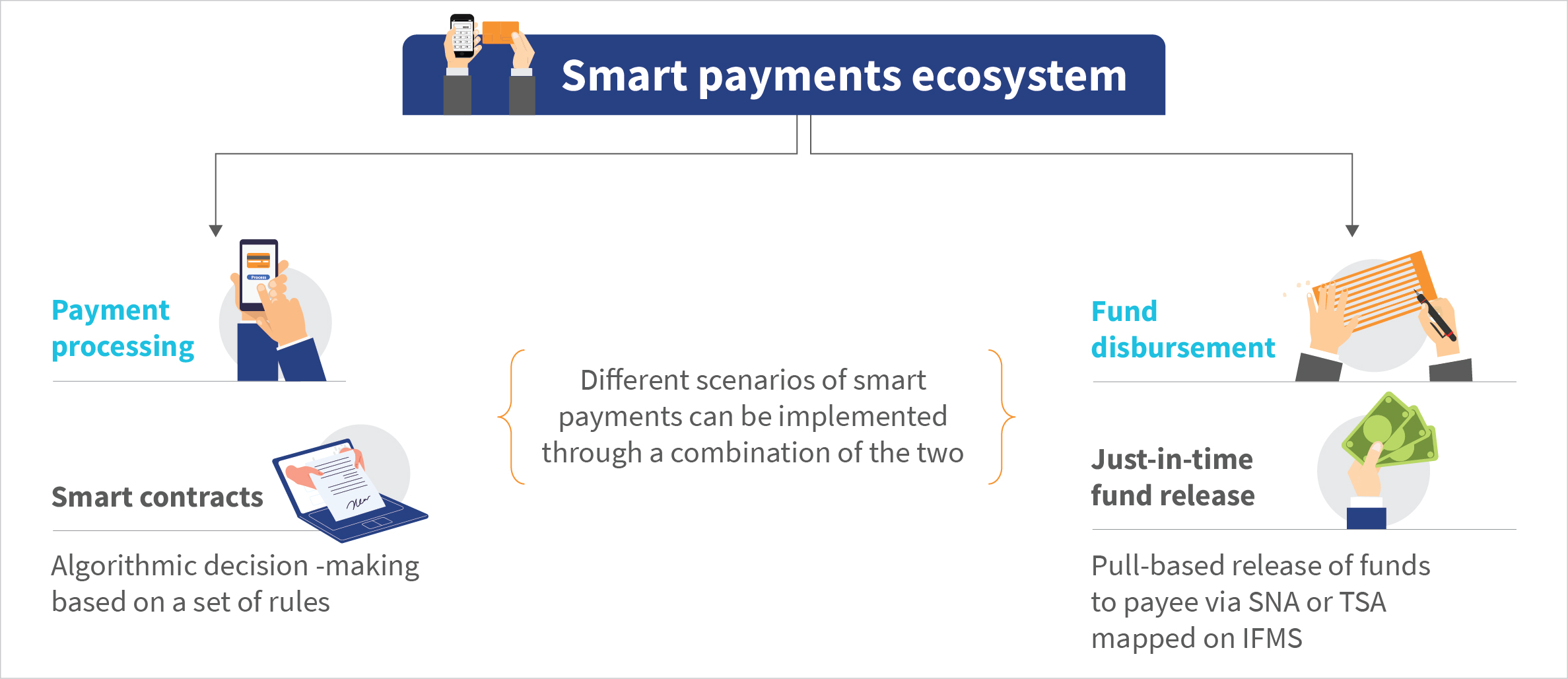

The concept of a smart payments ecosystem is built on digital PFM principles, such as a single source of truth or data, digitization of inputs at source, and demonopolization of access to services. At its core are “rules as code” or “if-then-else” algorithms that trigger actions and outputs when pre-defined payment conditions are met. Smart payments can be applied across diverse government payment scenarios, such as G2P, G2B, or G2G. We look at major components that must be developed to enable the concept of smart payments below:

- A single registry that acts as a single source of truth and is used to manage the payer and payee’s profiles;

- A business rules engine that configures rules and validates payment conditions;

- A payments engine with an entitlement calculator and a “decision-to-pay” trigger;

- A “just-in-time” system that rides on a virtual treasury single account (VTSA) and enables the assignment of virtual spending limits, such as a credit card instead of actual fund transfer as “authority-to-spend” to spending units, and allows them to pull funds in real-time per their needs.

As seen in the figure below, the first three points cover aspects related to payment processing, and the last one deals with fund disbursement.

Figure 1: The smart payment ecosystem

This versatile solution can be configured or developed to complement existing government processes and platforms, such as any existing workflow management solution and public fund management system.

Such a smart payments ecosystem is currently being experimented with, under the urban wage employment program, MUKTA, of the Government of Odisha’s Housing and Urban Development Department (HUDD). Early results from the impact evaluation have been promising. Within a few months of the pilot’s launch, the idle float has been eliminated, along with a 57% reduction in payment delays to beneficiaries and a significant reduction in administrative burden on officials. Complete implementation of the solution will reduce payment delays by 66%, from 120 days to less than 30 days—eventually to less than seven days—and reduce payment approval processing time from 16 to five days.

Lessons for India and the world

Besides the design of the smart payments solution, advocacy and consensus-building among government stakeholders and ecosystem players have been key planks in MSC’s journey to solve PFM challenges. MSC’s effort led to the adoption of solutions and influenced policy and regulations. Both government agencies, such as the Ministry of Rural Development and National Health Authority, among others, and state governments of Bihar, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Haryana, Assam, and Uttar Pradesh have shown willingness to implement smart payment solutions. The Government of Odisha has been a key implementing partner for this solution. Our successive blogs will discuss key lessons from these engagements and how they have helped us in our journey.

Given the sheer amount of transfers that governments make, the deployment of a smart payment system has the potential to unlock billions of dollars in government funds. For instance, in India alone, for FY 2024-25, the Central government alone has set aside USD 250 billion across 170 central sector and centrally-sponsored schemes. We hope that implementing the smart payments solutions system will provide the necessary fillip to expenditure management reforms that will organically link all the digital transactions along the expenditure chain, from budgeting to sanctions, raising invoices, approvals, and payments, and monitoring. This will significantly reduce the administrative burden on officials and enhance public service delivery across sectors, such as health, education, agriculture, and water and sanitation, to help governments realize their commitments and achieve developmental goals for their countries.