Full, yet undernourished? How India can move from food security to nutrition security

by Mitul Thapliyal, Puneet Khanduja and Neha Parakh

Jan 30, 2020

7 min

This blog presents the challenges faced by India to shift the focus of its public distribution system from food security to nutrition security.

India has been a food-sufficient country for more than 30 years – but it hasn’t always been that way. Though the nation now produces enough food for its entire population, recurring famines plagued it for decades. In response, the government strengthened the distribution system to prevent the large-scale loss of lives from starvation. Controlled and systematic distribution of food grains began in India under British rule during the Second World War. Then, after the country gained independence, the government modified the system of distributing essential food grains—known as the Public Distribution System (PDS)—multiple times to address the challenges associated with food security: targeting, procurement, storage and the transportation of grains to different parts of the country.

Presently, the National Food Security Act (NFSA) governs the PDS, guaranteeing supplementary food grains to 50% of urban households and 75% of rural households in India, and reaching almost 800 million people. Under NFSA, the PDS has considerably improved people’s access to food grains by covering a substantial part of the food grain requirement for most marginalized households. However, improving access to food is not the same as ensuring optimal nutrition.

The enhanced global focus on food and nutrition security

There’s a growing recognition of this reality in the development sector. Globally, modern approaches to food security are measured based on nutrition outcomes – not simply access to food. The objective of such programs is to ensure adequate nutrition for every individual using an overall ecosystem-based approach. For instance, the UN’s Zero Hunger Challenge program works to ensure that every person can enjoy their right to adequate food, while empowering women, prioritizing family farming, and helping food systems everywhere to become sustainable and resilient.

Countries such as the United States have also adopted such holistic approaches to food security, through its Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Similarly, the Food Assistance for Refugees program administered by the World Food Program focuses on health, food and also nutrition. At a larger scale, initiatives such as the Global Hunger Index focus on food security, nutrition and health indicators, measuring and tracking hunger at the global, regional and national levels.

The impact of poor nutrition in India

India has yet to fully embrace this focus on nutrition. Over the past few decades, programs such as PDS, Mid-Day-Meal (MDM) and Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) have evolved and improved in various ways. However, these efforts do not seem to have affected India’s nutrition indicators positively. An undernourished population affects the economic growth of the nation, resulting in productivity loss and otherwise avoidable health care costs. The World Bank estimates that India loses over US $12 billion annually in GDP from vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

But the impact of poor nutrition goes far beyond productivity numbers. The recently published Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (2016-18) highlights that 35% of Indian children under five years of age, and 22% of children between five to nine years of age suffer from stunting. Additionally, the report found that 33% of children under five, and 10% of children between five and nine were underweight. Even among adolescents between 10 to 19 years of age, 24% were found to be thin for their age. These statistics are further supported by the National Family Health Survey report of 2015-16. With long-running programs like the PDS working to improve marginalized people’s access to food grains, why are these nutrition issues so persistent?

Identifying the gaps in India’s nutrition programs

MSC has been seeking an answer to that question. An MSC study concluded in August, 2019 assessed the nutrition gap in households that receive support from the PDS. This study found that on average, PDS grains contribute to approximately 40% of an average beneficiary’s actual monthly food grain consumption at the household level. (The term “food grains” in this context includes rice, wheat, pulses and millets – grains which form the basis for all meals in India.)

The study also found that most beneficiary segments – comprising men, women, pregnant women, lactating mothers and children – had low levels of basic macro and micronutrients, including protein, fat, calcium, iron and folic acid. Clearly, the operational changes to targeting and outreach in PDS over the years have not led to significant improvements in the nutrition intake of beneficiaries. Similarly, the MDM and ICDS programs’ contribution towards nutrition intake of pregnant women, lactating mothers and children were not found to be optimal.

One of the obvious and primary reasons for undernourishment is a lack of dietary diversity. Ironically, PDS, which primarily supplies rice or wheat (or both) seems to be partially responsible for instilling dietary habits that lack in diversity: It sets the norms, and the staples it distributes are often exactly the same grains that beneficiary households already grow on their farms and consume from. Further, current PDS practices are so deeply entrenched in the beneficiaries’ psyches, that they are reluctant to accept modifications to the food baskets the program provides. For example, the government of the state of Andhra Pradesh implemented a laudable initiative and expanded its PDS food entitlements to include finger millet powder (a good source of energy, protein, vitamins and minerals), pigeon peas, and groundnuts. But MSC’s research revealed that most beneficiaries avoided these grains and consumed the food baskets’ rice exclusively.

How can India shift from food security to nutrition security?

In light of our findings, it’s clear that along with food modifications, nutrition literacy must be part of interventions that aspire to improve nutrition statistics. Studies from other countries that examine large-scale nutrition outcomes show that food choice and eating habits are influenced by a wide variety of factors, such as socioeconomic status, demography, ethnicity, convenience, advertising and even biological triggers. Additionally, the potential to incur lower health care costs has also been shown to influence food choices.

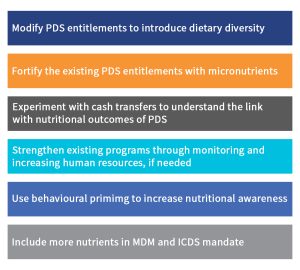

Considering these influences – along with the on-the-ground realities that enable access and encourage a willingness to choose more nutritious foods – MSC believes that a holistic strategy will facilitate the shift from food security to nutrition security. Practitioners should incorporate modifications to the existing programs and facilitate “nudges” to influence beneficiary behavior through positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions. We recommend the following ideas for practitioners to use in combination:

Let’s look at these ideas in more detail:

- PDS food baskets should include more dietary diversity, featuring local millets such as ragi and jowar, which are cheaper than wheat or rice. The program could then use the money saved to provide subsidized lentils to beneficiaries. This variety of food would ensure adequate dietary diversity among recipients. These interventions should accompany nutrition literacy initiatives to ensure uptake and penetration among the target population.

- Among our recommendations, the least expensive and easiest to implement initiative is food fortification, which should be carried out using WHO guidelines to inform the appropriate selection of safe fortification levels and modes of delivery.

- Many studies indicate that giving beneficiaries choice – e.g.: by transferring cash to recipients, so they can buy food items of their choice and preferred quality – improves the nutritional outcomes of food security schemes. Existing cash transfer schemes in India’s union territories should be further analyzed so that the model can be improved and replicated in other parts of the country. The cash coupon model (in which a combination of cash and food coupons allow beneficiaries to buy particular food items within the cash limit) should also be further tested to determine its viability at the national

- Existing programs such as Poshan Abhiyaan, Anemia Mukt Bharat, and Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committee are all designed with great objectives. But various reports highlight their implementation challenges. There is a need to increase ground level monitoring and training under these schemes to ensure better implementation.

- India should utilize behavioral science-based approaches that focus on local communities taking greater ownership (i.e.: embracing long-term sustainable changes that become a habit over time – unlike interventions that deliver either one-time or short-term benefits). The goal of these approaches would be to develop practical and workable solutions to help program beneficiaries adopt good nutrition practices. Together with nutrition literacy drives, these types of interventions would help solve demand-side issues that hamper good nutrition practices.

- The inclusion of additional micronutrients in existing nutrition-focused programs, such as the MDM and ICDS, is required to increase nutritional output. Additionally, supply chain oversight and data management should be more robust. Integrating technology into the delivery system of these schemes will help improve efficiency and efficacy.

What role can the private sector play?

The recommendations above open several opportunities for engagement with the private sector. Public-private partnerships can play a big role in the transition towards nutrition security, by bringing together experts, institutions and organizations that can help the government implement various nutrition-focused programs in different ways. These collaborations can focus on:

- Strategy: Private sector entities can be involved in designing the strategy and roadmap for new public initiatives. This could include various components, like research, advocacy, impact assessments, etc.

- Implementation support partnerships: Private sector players can provide support to the government as it rolls out the program at a large scale – as is the case with many other large public safety net programs run by the government. These support functions could include monitoring, evaluation and assessments.

- Supply chain and procurement: There could be additional possibilities for engaging with the private sector to procure micronutrients and manage the fortification process. Without many changes in terms of channel and logistics, fortified food could easily replace the food items provided under existing programs such as PDS, MDM and ICDS.

- Nutrition literacy: This has been one of the major drivers of persistent malnutrition levels in the country. We need to look for alternatives to ineffective approaches, and private sector players could provide new options for expanding nutrition literacy among the populace.

India’s economic growth projections are predicated on the assumption that, as a young country, its economy is likely to continue its rapid growth. But India will be hard-pressed to realize such growth if its population lacks appropriate nutrients and energy, and cannot contribute fully to society. That’s why it is imperative that the country optimize its food policy going forward. The above recommendations can guide the design of the government’s food programs, so that India may begin the slow march from food security to nutrition security.

The blog was first published on Next Billion on 29th January 2020

by

by  Jan 30, 2020

Jan 30, 2020 7 min

7 min

Leave comments