Triple Burden of Malnutrition in India – Are We Doing Enough?

by Puneet Khanduja, Aishwarya Singh and Mitul Thapliyal

Apr 28, 2018

4 min

The blog highlights how India is working to solve the problem of malnutrition.

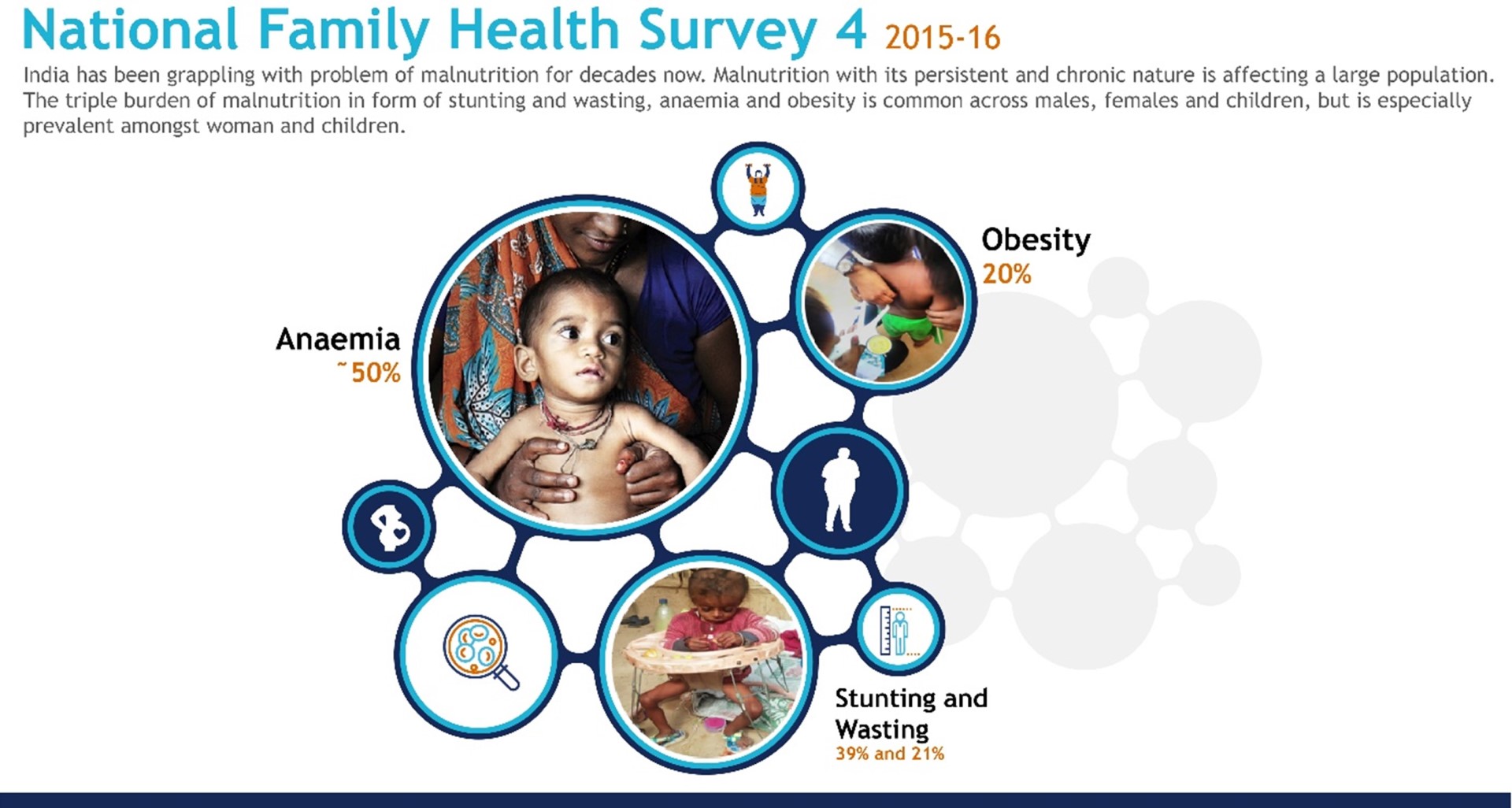

India has been grappling with the problem of malnutrition for decades now. With its persistent and chronic nature, malnutrition affects a large proportion of the population in the country. The triple burden of malnutrition in the form of stunting and wasting, anaemia, and obesity are common across women, men, and children, but is especially prevalent among women and children.

The level of public investment in the Union Budget for the financial year 2018–19 in form of subsidy on food and nutrition security has been substantial, at INR 1700 Billion (USD 25 billion). The enactment of National Food Security Act of 2013 institutionalised the importance of food and nutrition. However, the nutritional status of India’s population still remains compromised and has been a persistent problem despite measures taken by the centre and state governments. The country has witnessed significant economic growth, but its performance on nutritional indicators and hunger levels remain alarmingly poor. India ranked 100 among 119 developing countries in the Global Hunger Index of 2017. A complex range of barriers like culture, food habits, income and gender inequality, and social exclusion continue to thwart efforts to address the scourge of malnutrition.

The Government of India has rolled out a number of schemes in the past to combat this public health concern. These include Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), National Health Mission, Janani Suraksha Yojana, Maternity Benefit scheme, Mid-Day Meal Scheme and National Nutrition Mission. However, the results have been poor. The experience from the implementation of these schemes suggests that on-ground footprint and effective community engagement are vital to address malnutrition. Further, there is a great need to design such public interventions keeping the community in focus.

Global evidence suggests a shift from a strategy of Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) to Social Behaviour Change Communication (SBCC). This is because society and its culture have a deep impact on the habits and lifestyles of potential beneficiaries. A standardised approach to tackle malnutrition at the national level is not feasible given the social, cultural, economic, and geographic diversity in the country.

There is global evidence that suggests that having field functionaries or health workers from the community has a long-lasting impact on the behaviour of the target population. There has been a surge in the activity of these workers after the Alma Ata Declaration of 1978, which sought to address the shortages of professional healthcare workers to serve the last mile.

One plausible strategy, therefore, might be to appoint community-based catalysts for change – or voluntary field functionaries. These functionaries would understand the needs and culture of the society. They could help improve the implementation of public health interventions by serving as a link between the government and beneficiaries. Health and nutrition are dependent a wide range of variables that include culture, socio-economic status, equity, access to services and information, etc. Trained functionaries on the ground at the hamlet- or village-level would help assess and understand these complex, “softer” issues and their interplay with health and nutrition and impact on it. The functionaries would also be able to devise ways to address the issues at the local level within the constraints of the resource pool provided.

India already has its share of experiences with community workers in the form of Anganwadi workers (AWW) and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) under the Ministry of Women and Child Development (M/o WCD) and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (M/o HFW) respectively. AWW and ASHA have been entrusted to provide adequate healthcare to rural people and educate them on issues of preventive and promotional health care. However, their performance has been below expectations for a number of reasons. These relate to issues in the selection process, lack of clarity of roles, low capacities and skill-sets, excessive workload, weak supervision, low incentives, and lack of job security.

There is a need to work more closely with the community to address malnutrition. There is a need to work at the household- or hamlet-level to build their capacities to enable them to take control of their health. Volunteers from the community, especially women could spearhead movements, such as Jan Andolan1 to transform India from ‘Kuposhit Bharat2 ’ to ‘Suposhit Bharat3 ’.

Whereas ASHA and Anganwadi workers must serve a relatively large population (that is, around 200–400 families), the proposed new field functionary will be working at the hamlet-level with 10–15 families. They will have precisely defined roles and responsibilities. This will allow a more focused approach to address the complex web of issues around health and nutrition. The recently launched National Nutrition Mission may provide a conducive platform for building additional manpower at the hamlet level.

However, we cannot consider such an initiative as a solution to solve all the problems. India has suffered from the problem of weak implementation since several decades. The success of such a programme would depend largely on the following imperatives:

- Careful selection, training and accreditation (wherever applicable) of the volunteer workers at the grassroots;

- Convergence and linkages among various government departments for better outcomes of the public health programmes;

- Active monitoring of manpower in the public health domain;

- Supportive supervision for the field functionaries;

- Provisioning of an adequate compensation structure and timely payment;

- Meticulously planned job responsibility and performance indicators for the functionaries.

[1] Mass movement

[2] Malnourished India

[3] Well-nourished India

by

by  Apr 28, 2018

Apr 28, 2018 4 min

4 min

Leave comments