Women in the digital economy

by Manoj Nayak, Rhifa Ayudhia and Lenny Nurharyanti Rosalin

Jan 13, 2023

5 min

The COVID-19 pandemic carved out a prominent role for digital technologies in enabling economic transactions. However, the gender divide in access to digital technologies hurts women’s ability to participate in the labor force.

This blog explores the nature of women’s work and how digitization shapes it. We outline the opportunities and challenges in the digital economy and offer recommendations to ensure a fair digital economy for women.

Eighteen months after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the workforce had 13 million fewer women in employment in 2021 than in 2019. As social distancing mandates and lockdown restrictions impacted work, the role of digital technologies in enabling economic transactions became prominent. However, among men and women. Further, the gender divide in access to digital technologies and their use negatively women’s ability to participate in the labor force.

With this backdrop, the recently-concluded G20 Ministerial Conference on Women Empowerment in Bali, Indonesia, highlighted the need for a common gender framework to fulfill the goals of “Recover Together Recover Stronger.” MSC supported the Indonesian Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection (KemenPPPA) to articulate a vision to improve women’s participation in all forms of work in the digital economy.

This three-part blog series highlights the need to focus on women’s participation in the digital economy to reduce the gender gap in the labor force. The series focuses on informal workers, who represent 61% of the workforce worldwide, in the digital economy and their challenges.

Where do women in the informal economy work?

Most women in the informal sector work repetitive, low-skilled, and poorly paid jobs. Some broad categories of women’s informal work are:

- Home-based workers: Women in Informal Employment Organizing and Globalizing (WIEGO) defines home-based workers as those “who produce goods or services in or near their homes for local, domestic, or global markets.”

- Women as entrepreneurs or owners of small businesses: Women in this category run an enterprise, usually a nano- or micro-enterprise, as an income-generation activity. Most of these women operate from home or near their homes.

- Women in domestic work: Women in domestic work provide services in their employer’s private homes. These services may include sweeping, cleaning, cooking, and caring for children and the elderly.

- Women in the beauty and wellness sector: Women in this sector provide beauty and salon services either as part of an enterprise through an employee or are self-employed.

The four categories outlined here are not mutually exclusive, as women migrate between these categories depending on their situation. Yet, they struggle more in terms of limitations on time, mobility, resources, and social constraints than men, no matter the category of work.

The digitization of women’s work

As economies worldwide went into lockdown in 2020, digital platforms gained prominence as essential public infrastructure to provide key services. Digital platforms emerged as important intermediaries connecting service providers—workers—with the demand-side players—employers. Digital platforms opened new markets and extended work opportunities for women who previously lacked access to work.

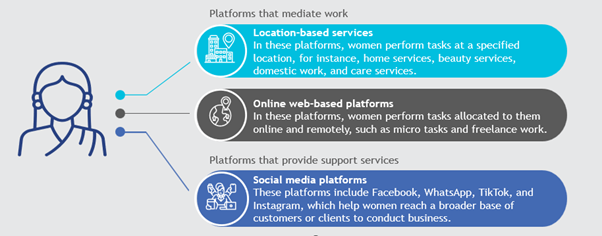

Digital platforms in G20 countries grew from 128 to 611 between 2010 and 2020, as per the ILO. Three types of digital platforms that have implications for women’s work are:

Opportunities and challenges for women in the digital economy

Digital platforms offer several options to women by overcoming some traditional barriers to women’s involvement in higher-value work. They reduce women’s barriers to entry and re-entry into the workforce. Their business models require digital platforms to focus on the professionalization and training of workers—and so some facilitate the training and skill development of these women. Research in India indicates that well-known apps and platforms formalize and legitimize women’s work. This benefit of digital platforms, coupled with the focus on professionalization, improves the social acceptability of women’s work.

However, the benefits of digital platforms vary across sectors or countries. Information and communications technology (ICT) can connect women to jobs and markets, overcoming several socioeconomic constraints. However, technology can also recreate and amplify existing inequalities in the labor market—disproportionately hurting women’s labor force participation. Evidence from India’s domestic worker sector shows the significant impact of on-demand digital work, which excludes women who lack digital skills, digital devices, or access to formal banking channels. MSC’s research with women’s cooperatives in Indonesia highlights similar challenges around access to digital platforms and their use.

Addressing key challenges will allow the digital economy to work for women

Identify and define different types of work in the digital economy

Labor regulations in most countries often do not protect nonstandard forms of work that lack a traditional employee-employer relationship. Informal workers remain invisible to the government in a regulatory environment designed for accessing worker rights with formal employment as the basis.

Such invisibility prevents workers from accessing worker protection measures, such as social protection, maternity pay, and statutory minimum wage. Many workers in the digital economy also lack access to worker protection measures. Besides, inadequate classification of gig or platform workers often excludes them from government programs designed to support informal workers.

Governments may have to modify existing laws to define and recognize gig and platform workers. This definition will help align government policy and implementation with workers’ needs and help them realize the full economic potential of this emerging class of work. An example of such modification is India’s Code on Social Security, which defined gig and platform workers for the first time.

Improve access to digital devices and tools for women

In the future of work, women’s access to digital infrastructure will determine their rate of participation in education, technological adoption, and the labor force. Women’s digital inclusion is imperative for them to participate meaningfully in the digital economy. About 18% of women, 315 million women, are less likely to own a smartphone than men. Similarly, the gender gap in mobile internet access is at 16%.

G20 member countries need to include the collection of gender-disaggregated data to understand the gender gaps in access and usage of digital tools, including access to the internet. Further, governments should devise innovative financing mechanisms that subsidize access to mobile phones and affordable internet services, such as universal access funds.

Create the infrastructure to improve women’s digital skills

Building skills for the digital economy is integral to ensuring sustainable growth and productivity in the future of work. Digital skilling programs for women need to consider the low levels of formal education in low- and moderate-income countries, leading to lower reading, writing, STEM, and language capacities. The gender gap in digital skills translates directly into lower economic benefits for women workers with lower skills to work in the ICT sector, creating thousands of jobs. Therefore, governments and digital platforms must apply a gender lens while designing skilling systems for the digital economy.

Policymakers and governments across G20 countries should focus on creating a skilling infrastructure that equips women with 21st-century skills, such as:

- The 4Cs—critical thinking, creative pitching, collaboration, and communication;

- Modern education enables them to access information on the internet, develop basic financial and digital literacy, and understand markets using social media and digital platforms.

Policymakers in each of the G20 member countries should strive to create a strategy that outlines basic, intermediate, and advanced levels of digital skills, specifically focusing on addressing the gender gap in digital skills. The implementation strategy should include a national baseline and target increasing the proportion of women and girls with a high level of digital skills.

Alongside the measures outlined above, achieving a fair digital for women informal workers will require efforts on two overlapping themes—adaptive worker protections for the informal economy and managing the transition to the formal economy—discussed in our subsequent blogs.

by

by  Jan 13, 2023

Jan 13, 2023 5 min

5 min

Leave comments