Women and DFS

by Graham Wright, Sonal Jaitly and Saloni Tandon

Mar 11, 2022

4 min

This blog highlights the key drivers of gender gaps in women’s access to digital financial services and their use. It shares how the adoption of DFS among women can catalyze the mitigation of this gender gap. It uses insights from a first-time DFS user’s journey to highlight how to understand and respond better to women’s exclusion.

The gender gap

Women face relatively higher barriers to using financial services at the bank or agent point due to their limited mobility and adverse gender-based norms. Although pivotal to accelerating the usage of bank accounts, digital financial services continues to be under-utilized, especially among women in India.

Key drivers of the gender gap

Women’s low utilization of bank accounts mainly stems from operational factors and limitations placed by social-cultural norms. On the supply side, a lack of focus on women’s needs and financial behavior remains a crucial driver to their low utilization of financial services. Banking products and services do not recognize that women and men have different financial behaviors deeply influenced by gendered social norms. For example, women prioritize privacy and savings. They have horizontal social networks, smaller economic geographies preferring to transact closer to home due to less free time available, and constraints on safe mobility. They also have varied lifecycle needs as they experience more transitions like marriage, maternity, and childbirth.

The promise of DFS in addressing the gender gap

DFS can help women overcome these barriers by offering solutions that they can access remotely, safely, and cost-effectively. Such solutions could be designed to enhance privacy and women’s control over their money. It could address women’s time poverty and mobility constraints by allowing them to transact at their preferred time and location. The solutions could also help them cope better with emergencies by making it easier for women to send and collect funds from different sources. Effective digital savings tools could help women with managing risk better and enhancing their financial asset base. A digital footprint of women’s transactions can also help make their creditworthiness more visible to banks and financial service providers.

Suffice to say, DFS could be a strong catalyst for women’s economic empowerment.

However, a substantial gender gap persists in the level of access to DFS and its adoption. GSMA indicates that 67% of women own a phone (gender gap of 15% points), 25% a smartphone (compared to 51% for men), while only 30% have access to the Internet through their phone (gender gap of 33% points). The limited adoption of DFS among women results from the blanket approach of DFS providers in targeting the masses.

Understand and respond to women’s exclusion

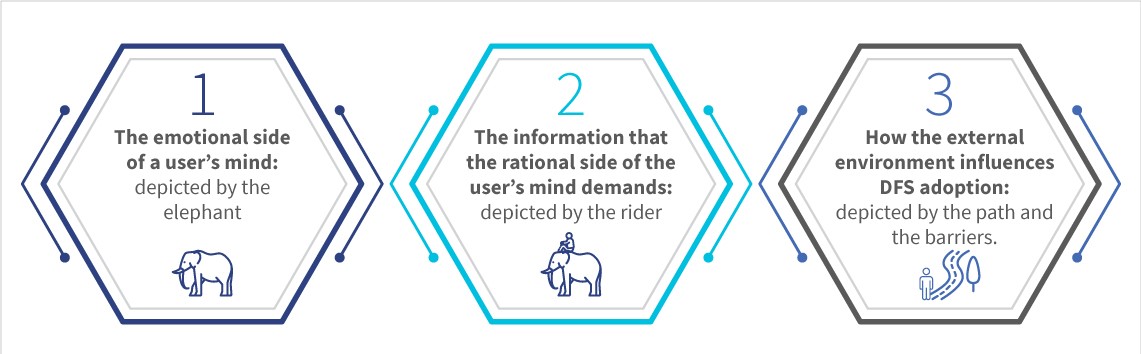

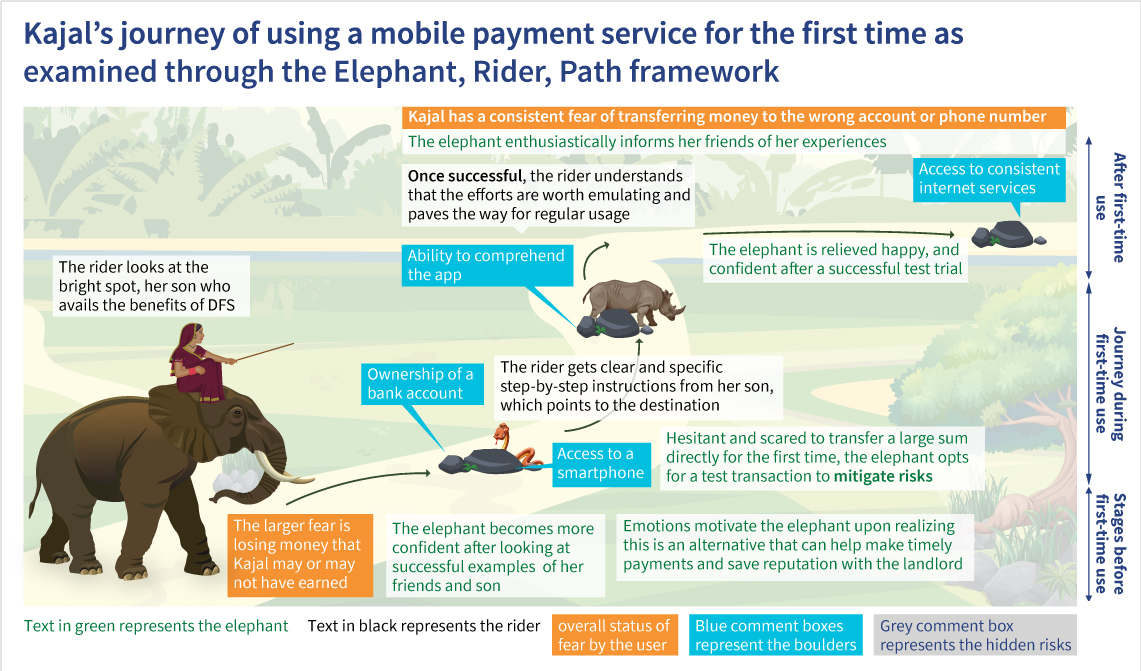

Inspired by the “Elephant, Path, Rider” framework by psychologist Jonathan Haidt, an examination of the journey of using DFS for the first time by men and women shows the interplay of the emotional and the rational mind for each step within the journey. The customized framework highlights three essential contributors to changing a user’s perspective to DFS and their interaction with it. These are:

The below is a snapshot of Kajal’s (a volunteer at Odisha Livelihoods Mission) journey of using a mobile payment service for the first time. Despite a positive experience, she hesitates to use DFS the next time due to her risk-averse nature and the limited availability of customer service to help with any errors she may make.

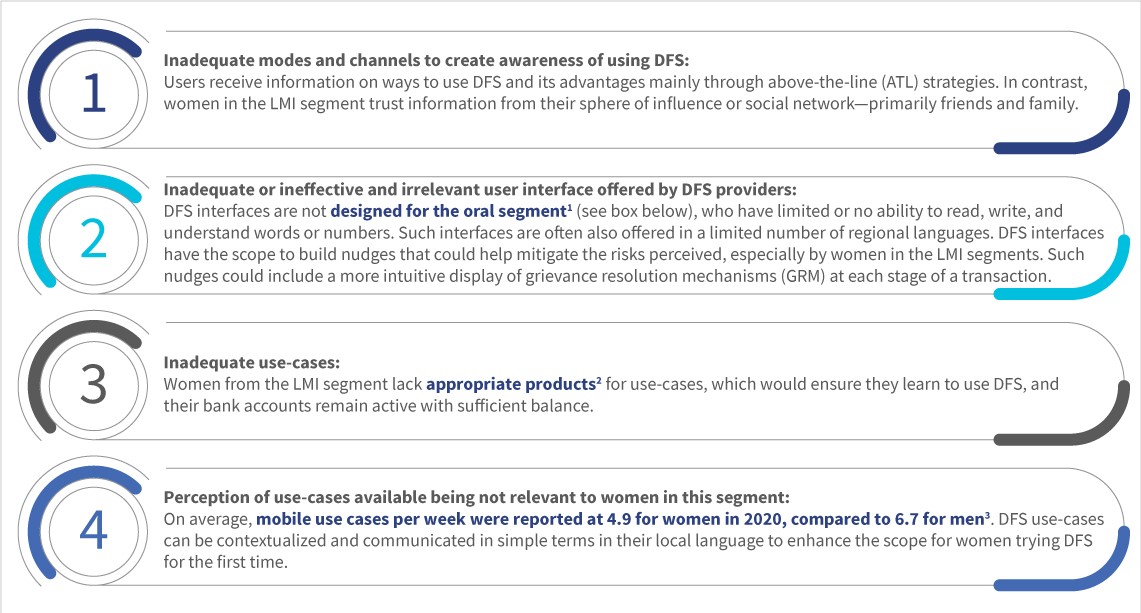

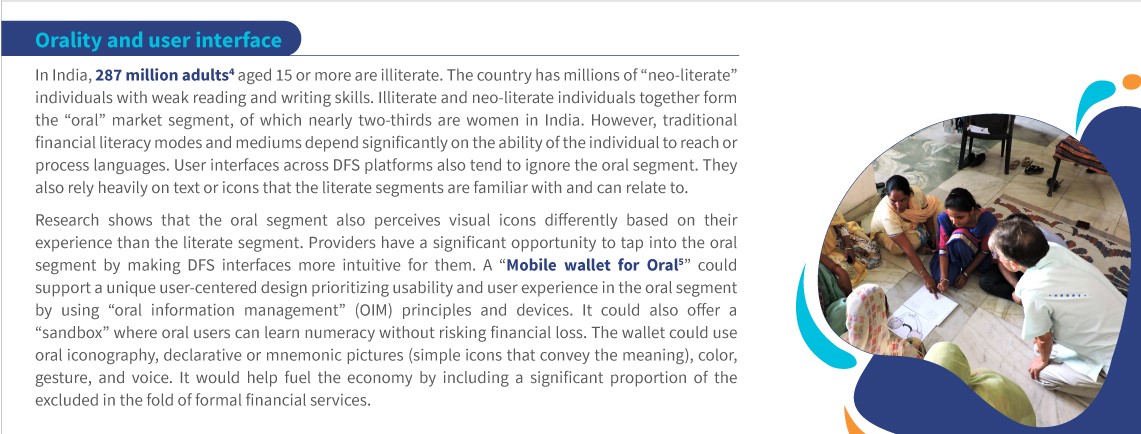

This examination has helped identify the following critical factors that contribute to limiting the uptake of DFS, especially among women:

The government’s response

Government departments have undertaken several initiatives to enhance the use of financial services, including DFS. These initiatives include efforts undertaken by the Department of Financial Services, the Ministry of Rural Development, and NITI Aayog. They focus on enhancing access to financial services among women and ensuring account ownership at the last mile.

Since 2016-17, State Rural Livelihood Missions (SRLMs) in several low-income states have steadily identified, trained, and deployed eligible SHG members as BC agents in association with banks. These states comprise Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh. In February 2020, 6,094 Bank Sakhis across 12 states collectively completed 748,454 transactions worth more than INR 2.7 billion (USD 37 million). The Targeted Financial Intervention Inclusion Programme launched by the Department of Financial Services, Ministry of Finance, also worked to ensure an access point within 5 km of each village, especially in the 112 aspirational districts.

Conclusion

While these government initiatives are laudable, the complex range of physical, social, and psychological barriers mean that they are unlikely to be adequate, even if they achieve scale. If India intends to achieve real digital financial inclusion for all, it will need to expand the financial services space for millions of low-income women.

Expanding the financial services space would require creating convenient access, valuable use-cases, exposure, and trust-building—first through assisted access to DFS. Female BC agents at the last mile could be a critical channel to encourage exposure, build trust, and ensure a positive first experience of DFS for women users. These local agents are an integral part of the community and enjoy women’s trust. Ultimately, these agents could provide women with the skills, confidence, and trust to use digital tools to conduct self-initiated transactions—especially if they can get their hands on intuitive user interfaces.

1 2017, MSC, Lessons from Orality for Digital Financial Services Development

2 2020, MSC, Opinion | Designing financial products for women

3 2021, GSMA, The mobile gender gap report 2021

4 2014, Hindustan Times, India has highest population of illiterate adults at 287 million: UN report

5 2016, MSC and My Oral Village, Digital Wallet Adoption for the Oral Segment in India

by

by  Mar 11, 2022

Mar 11, 2022 4 min

4 min

Leave comments