When inclusion is not inclusive: What needs to change to achieve meaningful financial Inclusion for women

by Bhavana Srivastava, Akhand Tiwari, Rahul Chatterjee and Abhishek Gupta

Jan 17, 2020

5 min

Financial inclusion sector’s combined efforts have not succeeded in making an impact on women. Mainly for reasons – significant variations in their behaviour and ecosystem players generally overlooking gender centrality in the design of financial products and services

Samina and Malti live in a village in a central-eastern district in Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state in India. Both opened a bank account in 2016. They had come to know about the PMJDY scheme (a flagship financial inclusion product of the government of India) from their husbands. Malti has since been using the account to only receive remittances sent by her husband, who works in another town. Samina, however, has never used the account. She doesn’t even know what has happened to that account.

Both Samina and Malti have contributed to India’s impressive growth rate in women’s financial inclusion — recent statistics show that 79% of women in India are financially included (FII 2018). But are they, and the many women like them, who have such accounts truly financially included?

This question is troubling — not just for us at MSC, but for the entire global financial inclusion community. We wonder if the sector’s combined efforts are failing to make an impact on women, ensuring that they actively use and benefit from their financial accounts. A recent study by MSC on women users throws some light on this challenge. The study’s findings indicate that we are overlooking two simple, yet extremely important aspects of the issue: first, that women are not a homogenous group and the significant variations in their behavior and engagement with formal financial services should be appreciated; and second, that ecosystem players generally overlook gender centrality in the design of financial products and services.

Women are not a homogenous group

When measuring financial inclusion, we tend to make a traditional binary classification between “users” and “non-users” of financial products. But this is fundamentally misleading. In fact, there are six distinct sub-segments of women, when it comes to financial services usage:

- Advanced users are financially independent, using multiple banking and other financial products.

- Regular basic users have regular cash flows into their accounts, either from remittances or wages.

- Irregular basic users have irregular cash flows into their accounts, leading to less experience with formal financial services.

- Proxy users have accounts operated by someone else in the family (primarily husbands or other male family members).

- Dormant users have an inactive account.

- Excluded women do not have a formal financial life, particularly a bank account.

Financial services providers (FSPs) need to cater to each of these groups appropriately. To that end, much can be learned from the fast-moving consumer goods industry, where a particular soap or face wash is presented in a variety of ways to serve the diverse needs of different sub-segments of women customers, and retailed with different stock-keeping units (SKUs). The financial services industry also needs this sort of nuanced understanding of women customer sub-segments.

Lack of gender centrality in financial product design

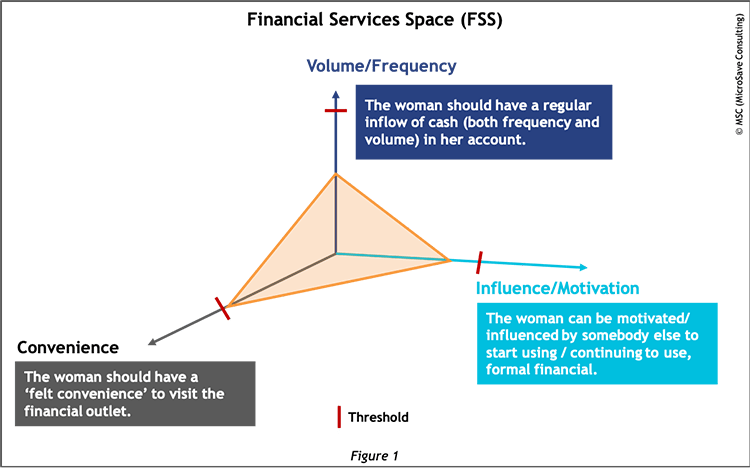

We define gender centrality as a way to recognize that women and men have different needs, aspirations, perceptions and behaviors, which are influenced by prevailing social and cultural norms and associated inequalities. We need to apply this understanding to the design, delivery and provision of financial services. The financial services space (FSS) framework below clearly highlights the importance of gender centrality. The FSS framework explains the distinct and diverse groups of women in terms of their financial behaviors, and the “triggers” that can bring out the behavior changes that will lead to increased financial inclusion.

An FSS (see Figure 1) can be understood as a three-dimensional space that represents a conducive environment for a person to conduct financial transactions independently. Each woman user has a unique FSS — determined by thresholds on each dimension. Ideally a woman needs to cross the threshold of all three dimensions to start using financial services, and to sustain the usage. However, if a woman crosses the threshold for even one or two of these dimensions, it can lead her to use financial services, including digital services.

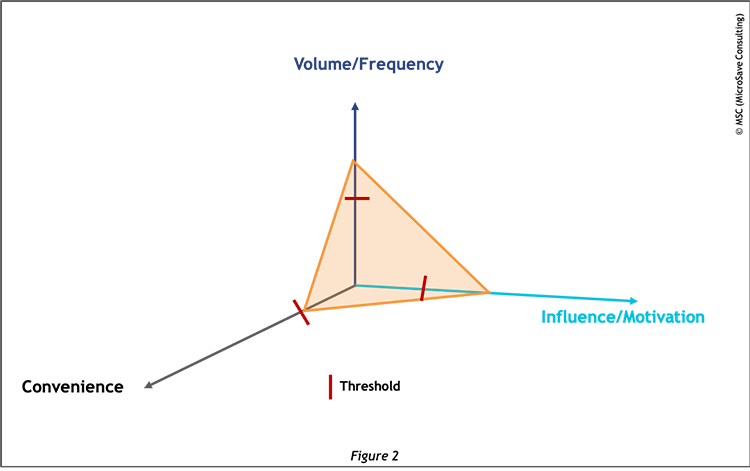

The FSS in Figure 2 is for a regular basic user like Malti, who we introduced at the beginning of this article. Malti has crossed the threshold for all three dimensions: The suggestion by her husband acted as the motivation factor to open the account; the regular remittances he sends covers the dimension of volume/frequency; and the digital financial services (DFS) agent in Malti’s village makes the cash-out operation quite convenient for her.

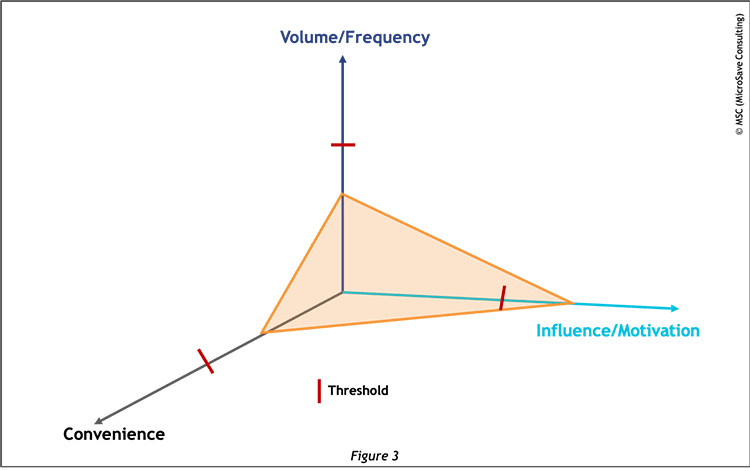

We find a completely different FSS for our dormant account holder Samina. As Figure 3 indicates, Samina has a restricted FSS. The motivation component of her FSS was quite high when she first opened her account. However, the volume of her needs has been small — she does not have a regular cash flow or income, so she does not need to use her account. The convenience component is low as well — because of her restricted mobility (imposed by social norms) she does not go out of her house alone anyway, and is not able to realize the benefits of banking services offered via agent networks. As a result, her bank account has remained dormant.

This recent MSC study shows that each of these three FSS dimensions has its own triggers that can often be generalized for specific user groups. For example, in the case of volume/frequency: Income, government-to-people transfers and remittances are the most common and important triggers. Similarly, in the case of convenience: Access (in terms of distance/time) and confidence are crucial triggers that dictate the financial services space for any customer sub-segment. For the dimension of motivation, we found that family and financial services providers (especially DFS agents) are the important triggers. For example, the convenience dimension of FSS for both irregular and proxy users can be enhanced by gender-sensitizing the male/female DFS agents on how to better serve women customers’ needs (they can provide women customers with assistance in making transactions, to overcome the ever-growing digital divide). Ultimately, these agents could provide customers with the skills, confidence and trust to use digital tools themselves, so that they can conduct self-initiated transactions.

These triggers provide useful insights to financial services providers to help them address the needs and aspirations of each sub-segment uniquely, rather than providing them with basic, standardized products (sometimes even disguised as “gender neutral”) — a practice that has been the norm. This will help to bring more women users to advanced financial inclusion.

It is time to rethink financial services for women, viewing it through the lens of gender centrality. A holistic approach with gender-centric policies and products can bring about this change. The sector is already progressing in this direction through initiatives like AFI’s GRID framework, which aims to increase women’s financial inclusion using DFS. But there are still promises to keep — and miles to go.

The blog was first published on Next Billion on 14th January 2020

Leave comments

Hugh Allen

27 Jan, 2020

Good analysis. I have long wondered why financial inclusion is defined as having a connection to the formal sector and, along with it a sense of 'job done.' Financial inclusion can simply mean being able to access services that are useful, accessible and easy to understand. Often that can mean belonging to a savings group. Sometimes it can mean having a highly active account at Chase Manhattan, plus a stock portfolio and a truckload of useful debt. The key distinction is, in my experience, the predisposition or desire to advance economically without massive learning curves and disruption to the pressing rhythms of the household. The more a person engages with the wider economy the more they are predisposed to reinvest in their businesses and take advantage of financial services that are biased towards debt finance. The more they simply want to be more secure and less vulnerable to exploitation, the more that savings is important and the pressure to take drawings from a microenterprise is reduced. Crucial, in this case, is the support of peers in the community and the more that local, quasi-informal services are the most appropriate form of inclusion. I wish this was more widely recognized and that formal inclusion is not the prime objective.

by

by  Jan 17, 2020

Jan 17, 2020 5 min

5 min

Comments (1)