Universal Basic Income: A policy option for India?

by Kushagra Harshavardhan and Noel Johns

Mar 3, 2021

9 min

With governments around the world rushing to mitigate the economic fallout of COVID-19, the idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) has gained prominence. This blog analyzes the suitability of UBI in the Indian context.

Governments around the world are rushing to mitigate the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly on lower and middle-income groups. Among the range of proposed responses, the idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) has gained prominence. The United States has already begun providing cash transfers of USD 1,200 to all taxpayers, adjusted depending on income levels, while Spain is considering a minimum income transfer to vulnerable households to provide subsistence assistance and catalyze economic activity. The political and academic circles in India to have seen similar calls for a UBI in the country as a financial safety net to tide over an uncertain labor market in a post-COVID-19 scenario. Given the renewed interest in UBI, this blog will analyze the suitability of UBI in the Indian context.

1. What is UBI?

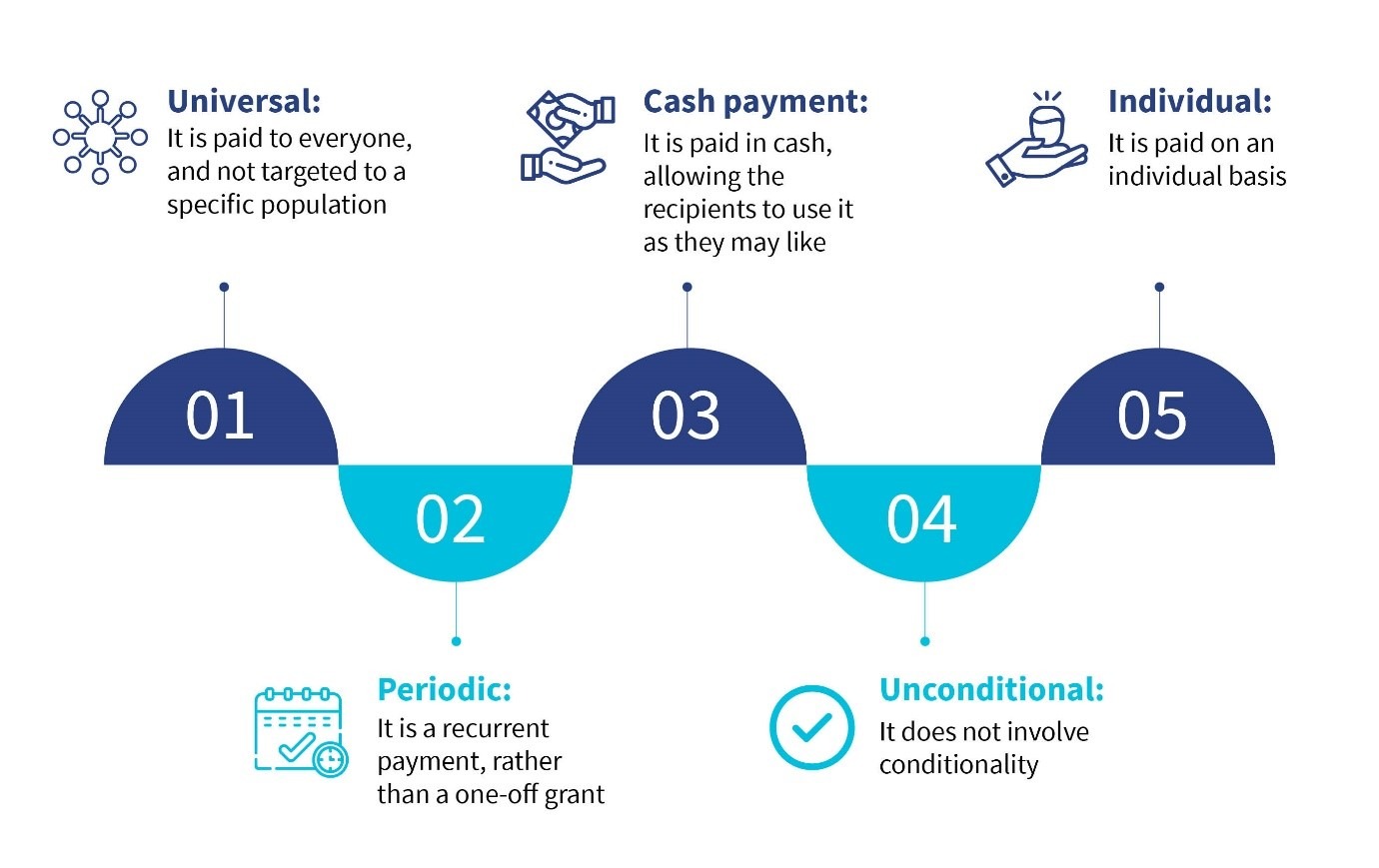

Universal Basic Income has taken distinct forms in different contexts depending on historical and geographical factors. While there might not be a standard definition of UBI, the fundamental tenants include:

The concept of a UBI has both proponents and detractors. In developed countries, proponents of UBI recognize it as a solution to rising inequality and unemployment precipitated by technological advancements. Many see it as an alternative to the cumbersome “welfare state” and as a tool to alleviate poverty and provide a social safety net by covering subsistence needs. It is also favored in certain geographies like India because it gives more choice to recipients who currently receive in-kind transfers. Further, UBI seems appealing due to high administrative costs, leakages, barriers to enrolment, and inaccurate targeting that plague existing welfare initiatives.

On the other hand, critics of UBI, in both developed and developing countries, argue that a UBI would not be fiscally feasible to implement. They believe UBI defeats the objective of economic redistribution, discourages productive activity, and sparks inflation.

While a national implementation of UBI has not yet occurred, there have been multiple attempts to pilot variants of UBI or unconditional cash transfers at smaller scales in different countries. The charity GiveDirectly conducted trials on the effect of providing unconditional cash transfers to households in Siaya County in Western Kenya during 2014-2016. This exercise provides insights into the effects of a potential UBI.

The study found that 18 months after receiving the cash transfers, recipient households reported higher spending and an increase in durable assets. The higher demand for products and services also resulted in increased income among non-recipient households, which led to increased spending. However, the study reported that the gains accrued due to the income transfer were also unequal, with the households that were already well off gaining more than the poor households. This amplified the existing income inequalities in the village.

In Namibia, a two-year pilot project (2008-10) on a Basic Income Grant (BIG) was implemented in the Otjivero-Omitara area. All residents under the age of 60 received NAD 100 (USD 6.7) each month without conditions attached. The positive impact of the project included lower household poverty levels alongside increased attendance and lower dropout rates in schools. However, since the BIG was only implemented in Otjivero-Omitara, there was a significant migration towards the area, resulting in a 24% decrease in per capita income.

2. UBI in the Indian context

There have been trials on UBI in India, as well. SEWA Bharat, supported by UNICEF India, conducted a pilot on basic income transfer in the rural areas of Madhya Pradesh from 2012 to 2013. For the pilot, two categories of villages were identified—village and tribal village. For each category, a set of control villages was identified. An amount of INR 300 (USD 4) per adult and INR 150 (USD 2) per child as basic income was distributed unconditionally to all individuals within the village for 12 to 17 months, without imposing eligibility requirements. The results were encouraging with pilot villages performing better on parameters including open defecation, electricity connections, drinking water, nutrition, and food sufficiency when compared to the control group.

The Government of India’s (GoI) Economic Survey 2016-17 catalyzed discussions around UBI in India. These discussions explored the possible effect of UBI on various social development parameters, such as poverty reduction, social justice, and administrative efficiency. The discussion, in part, focused on the significant number of central sector and centrally sponsored sub-schemes (950) in India, such as food and fertilizer subsidies, employment guarantee programs, and scholarships, among other social assistance programs.

These schemes have varied targeting mechanisms, conditionality requirements, and modes of implementation. These targeting mechanisms are often crippled by exclusion and inclusion errors and high bureaucratic costs, resulting in inefficiencies and sub-optimal effectiveness. GoI’s Economic Survey 2016-17 posited that the implementation of UBI could substantially overcome these issues.

We could argue that over several decades, the GoI has taken small steps toward a quasi-UBI by implementing different modes of Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) programs. The cash transfer in food subsidy pilot (2015) in the three union territories of Chandigarh, Puducherry, and Dadra and Nagar Haveli is an example of the shift from in-kind to cash transfers by the GoI. Under this pilot, all beneficiaries of the Public Distribution System (PDS) were entitled to receive cash transfers instead of rations received through PDS shops. Overall, beneficiaries were indifferent, yet the monetary savings realized by the GoI was significant in the range of 10% to 15% of the food subsidy bill.

Another unconditional and recurring income transfer program launched by the GoI in 2018 is PM Kisan, which entitles all landholding farmers to INR 6,000 (USD 80) annually. PM Kisan most closely mimics a UBI in India with the only conditionality being that the recipient must qualify as a landholding farmer, subject to a few exclusions. Over time, the program is expected to cover 140 million beneficiaries. These policy measures have created an environment in which the GoI could shift to UBI without significant friction in the future.

3. Designing an Indian UBI

The transition from existing government social welfare subsidy payments to UBI would require the GoI to address questions around eligibility, frequency, and amount of basic income to be provided. Yet questions remain around whether the government can comprehensively implement UBI, or if it would require a tailor-made approach. The following section details ways to address some of these foundational issues.

Is universality an option?

One of the core precepts of UBI is that it is universal in nature, which means all the citizens are, by default, beneficiaries. Adopting a universal approach in India would certainly result in higher government expenditures, while simultaneously ensuring that no citizens are excluded. This approach does away with the traditional mechanisms of delivering subsidies prevalent in India, which include defining a universe of beneficiaries and selecting from that universe.

Yet implementing UBI would be unaffordable in a country like India, where 22% of the population is classified as below the poverty line. This is because adopting a UBI would come at the cost of providing benefits to upwards of 78% of the population who would not need it immediately.

A better model for India would be to start with a targeted approach. Although this appears to be more affordable, it has its own set of challenges, including those around identifying the target segment (the poor) and limiting the flow of benefits to them. A targeted approach would require a robust database of beneficiaries and clear guidelines around exclusion parameters. Such an approach has always been subject to exclusion and inclusion errors. While wrongful inclusions lead to unnecessary expenditures, wrongful exclusions defeat the program’s purpose.

To address this, the GoI should develop a dynamic database in the long term, which can be used for beneficiary identification. The Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC, 2011) can be utilized for immediate rollout since it captures the socio-economic profile of households in the country comprehensively. Although a targeted approach would stop short of a true UBI, it would have a significant impact on India’s population living below the poverty line. For a developing country like India, a quasi-universal basic income makes greater economic sense.

Can a UBI be a substitute for the existing welfare system?

The second major issue to be addressed is how a UBI would fit into the existing social welfare ecosystem in India. Estimates indicate that a UBI designed as a full supplement to existing social welfare schemes in India would add up to 13% of the current GDP and, therefore, is not fiscally feasible. On the other hand, the existing discourse (including the Economic Survey of 2016-17) rests on the idea that a UBI budget would replace all existing welfare programs. However, there are multiple issues with this approach.

First, rolling back programs meant to ensure food security and improve educational outcomes and sanitation, among others, would not only require backtracking on the achievement of human development goals but would not be politically viable. Welfare infrastructure, such as health care centers, plays an important role in nudging beneficiaries toward responsible behavior, particularly through social proofing.

Second, directly substituting UBI for the existing in-kind welfare programs ignores the additional transaction costs that would be borne by beneficiaries. These transaction costs include transport costs to access cash from banks, and wages lost as opportunity cost during travel and wait time. Third, some beneficiaries have expressed a preference for receiving in-kind subsidies—imposing a UBI ignores this preference. Fourth, clubbing existing benefits to make way for UBI will need a systemic overhaul because there are many backward and forward linkages. For example, PDS is linked to the Minimum Support Price (MSP) provided to farmers.

Finally, evaluation of cash transfer programs has thus far shown significant last-mile challenges including enrolment problems, Aadhaar seeding and authentication issues, delays in transfers, and gaps in grievance resolution.

Perhaps rather than view this as an “all or nothing” choice, policymakers should look at the middle road by implementing a supplementary income transfer to the targeted population. The GoI should retain existing in-kind programs that deliver necessities and enhance one’s quality of life, such as food security, sanitation, and education. Over time, once the GoI demonstrates that it has built a stable system that can reach the poorest through income transfers, it could revisit certain policies including giving beneficiaries the ability to select from different service providers, that is, existing public services or non-government providers.

This will empower beneficiaries by allowing them to decide how their social welfare funds could be spent. It could also potentially enhance the quality of public services by introducing competition with private or civil society organizations to attract business from the poor. In the long run, this could usher in greater accountability and efficiency among service providers.

Conclusion

Designing an Indian UBI requires an understanding of the constraints of the feasibility of universality and substituting existing welfare subsidies—and tailoring the program accordingly. In essence, a UBI in India could be implemented as a supplemental, unconditional, recurring cash transfer to the target population while keeping the existing welfare infrastructure intact. This approach mitigates concerns regarding financial viability by making incremental shifts to the welfare delivery ecosystem and introducing more choice to beneficiaries.

However, the GoI should first conduct a pilot study to understand the short-term and long-term effects that a basic Indian UBI would have on incomes, labor markets, communities, and beneficiary preferences. Only then should it throw its weight behind what is an extremely complicated and far-reaching program.

References;

What is UBI?, Stanford University

SEWA Bharat is a federation of women-led institutions that provides economic and social support to women in the informal sector

USD = INR 75

‘Piloting basic income transfers in Madhya Pradesh’, SEWA Bharat, January 2014.

The Economic Survey of India reviews the developments in the Indian economy over the past financial year, summarizes the performance of major development programs, and highlights policy initiatives of the government and the prospects of the economy in the short to medium term.

Central Sector Schemes are the programs that are entirely and directly funded and executed by the central government.

Centrally Sponsored Schemes are programs that are implemented by state governments. However, the cost of these schemes is borne by the central and state government on a shared basis. Under the cost ratio, the larger portion is always borne by the central government.

The exclusion error fails to target the intended beneficiary population of the scheme. In contrast, the inclusion error causes funds to be spent on non-deserving populations, which leads to inefficiencies and budget increases.

Economic Survey of India 2016-17, Government of India; Himanshu and Abhijit Sen (2013), “In-kind food transfers—I: impact on poverty,” Economic & Political Weekly Volume 48 Issue No. 45-46.

Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) is a mode of delivery of G2P payments launched by the GoI to transfer benefits and subsidies of various social welfare schemes directly into the bank accounts of beneficiaries.

Written by

by

by  Mar 3, 2021

Mar 3, 2021 9 min

9 min

Leave comments