Trust Busters! A dozen reasons why your potential customers do not trust your agents (particularly in rural areas)

by Graham Wright, Nitish Narain and Raunak Kapoor

Feb 18, 2020

7 min

Alarmingly, most users who sign up for digital financial services do not actually end up using them, largely due to a lack of trust in agents. This holds true even in the case of relatively “advanced” geographies. “Trust busters” examines the evidence and lists out 12 reasons behind this worrying trend of interest in agency banking that fails to convert into regular usage.

So why do people not use agents? In part, for rural people at least, because agents they are not available in or near their villages. But also for a range of reasons around their trust in those agents. Indeed, for many consumers, the kirana (grocery) store is not a desirable agent. This is because storekeepers are often key influencers of village gossip or are at its epicenter. Thus, a storekeeper who acts as the local agent presents a risk of loss of confidentiality within the community. Moreover, many households borrow from the store in times of need, so a storekeeper who is an agent creates a very real risk that the money they cash out may be commandeered to pay off debts.

Furthermore, many rural people travel each week, or every two weeks, to local market towns to perform tasks and conduct a variety of transactions. Therefore, they can go to the bank or to another agent in the market town frequently, with limited marginal costs. This option, however, overlooks two key factors in favor of continuing work to extend the “agent frontier” to establish agents closer to remote rural villages.

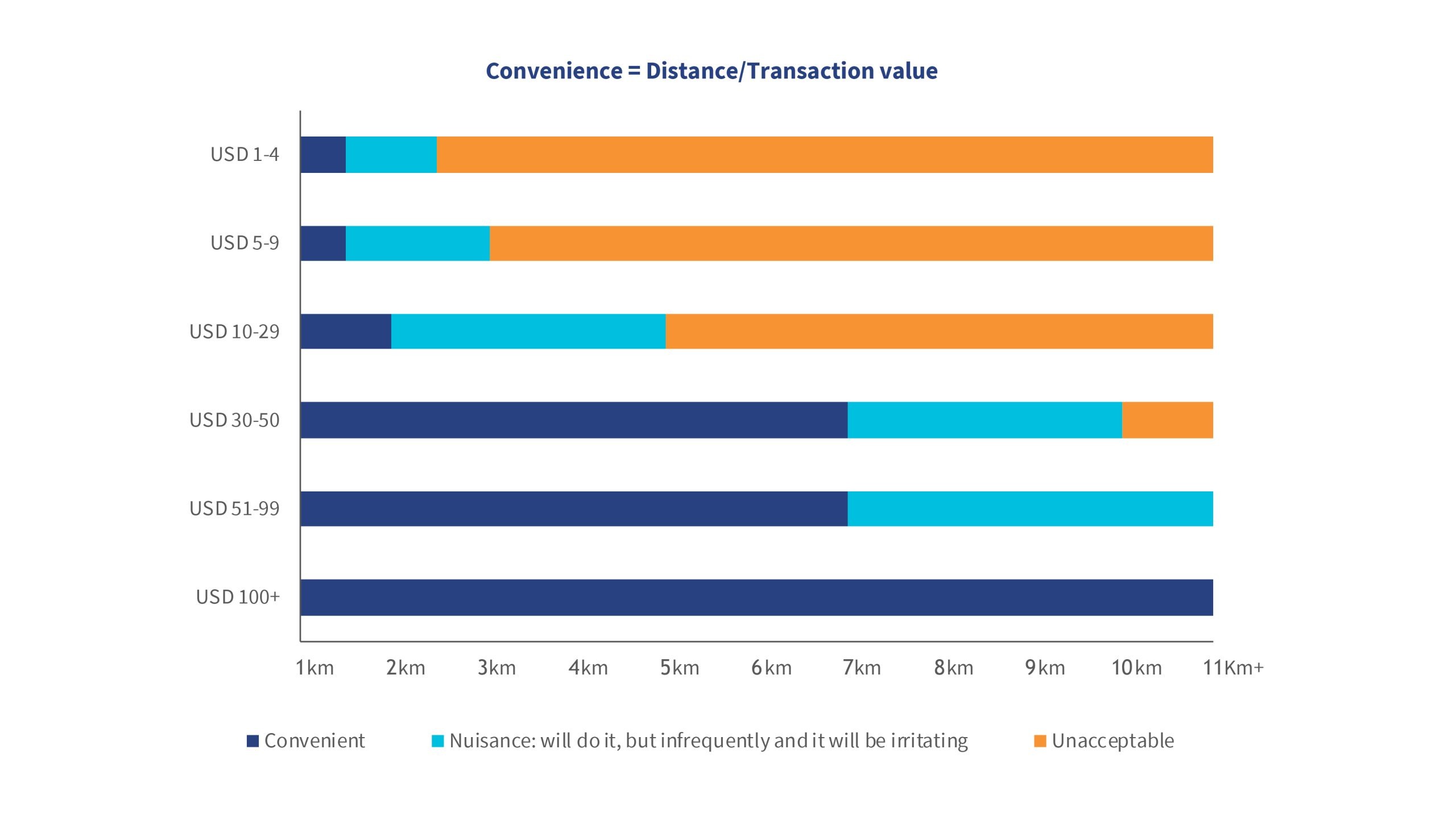

The first factor is gender—in many countries, only men travel to the market town. Yet, women want and need to conduct many of their financial affairs in confidence, often without the knowledge of their husbands. Access to agents within the locality will enable women to conduct financial transactions on their own. The second factor is small transactions, particularly savings, which can be encouraged by having agent points nearby. As IFC has already pointed out, the larger the transaction, the further people are willing to travel to conduct it (see figure below). Therefore, if we wish to help people save by putting aside small amounts outside the house, and thus away from the temptations of “frivolous spending”, or from the predations of marauding relatives, they will need an agent nearby.

These, and other issues related to the digital divide, make the work of MSC, BCG, and CGAP on expanding the rural frontier critical. Creative, country-specific solutions will be essential to enable profitable agents beyond the current frontier. Such solutions include:

- Differentiated agents and enhanced commissions for processing G2P payments in India;

- Alignment of regulations, particularly on who is permitted to be an agent and what products they are allowed to offer, as well as commissions for processing G2P payments in Indonesia;

- Broadening the range of products offered by mobile money agents across Africa;

- Enhancing the number, role, profile, and support for female agents across South Asia and parts of Africa;

- Leveraging technology to achieve efficiencies in “Distribution 2.0”; and thus ultimately

- Re-imagining the last mile of agent networks.

MSC conducted its initial analysis of consumer protection issues in India in 2016 as the BC agent model was rolling out at scale. We found that many people trusted the agents—not least of all because they were dependent on agents to conduct “agent-assisted” transactions. This seems to be changing. In our extensive fieldwork across India, we are increasingly hearing a dozen issues that are eroding trust in agents.

And the problem is not confined to India…

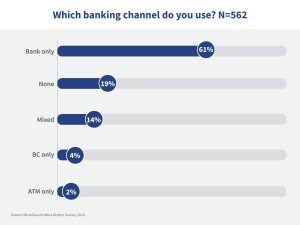

We drew similar conclusions of our analysis of the operations and impact assessment of the PKH conditional cash transfer system in Indonesia. We found that only 18% of beneficiaries used agents to withdraw their funds. In part, this was because agents are simply not present in many rural areas, so beneficiaries have to go to the nearest ATM. Yet even in areas where agents are present, many lack the liquidity to provide the big cash pay-outs as beneficiaries withdraw the entire PKH payment in one go.

As a result, even PKH facilitators and banks discourage agents as cash-out points. Moreover, agents charge informal fees to make cash payouts. The median fee charged is IDR 10,000 (USD 0.73) per disbursement, which makes ATMs more cost-effective.

Once again, consumers have lost trust in the agents’ ability to meet their needs in a transparent and honest manner.

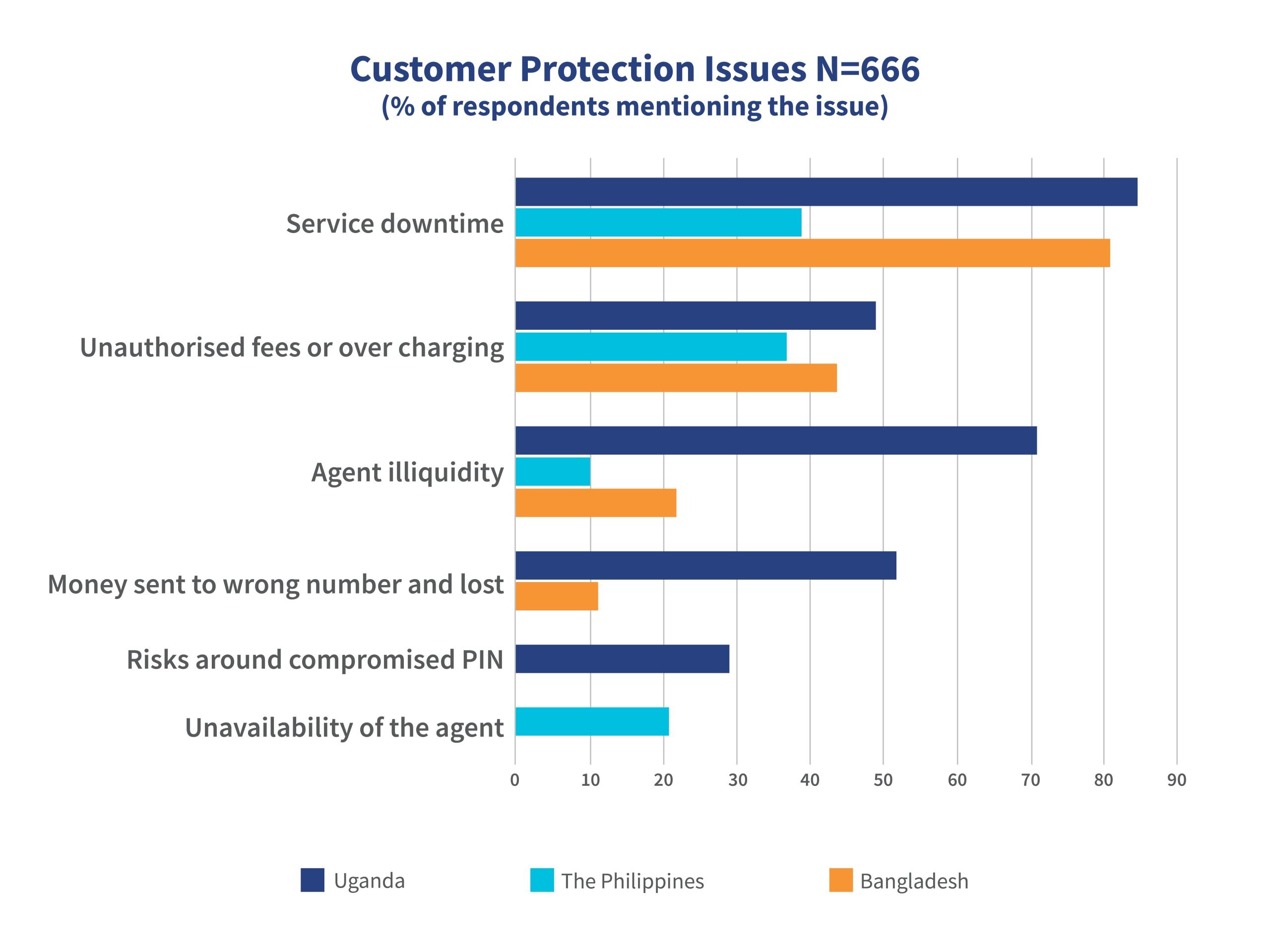

We picked up similar issues in our study on customer service for CGAP back in 2015, when we identified three key issues that were eroding the trust of customers in three different, but relatively mature markets. These issues were 1. Service or network downtime; 2. Unauthorized fees charged by agents; and 3. Agent illiquidity.

It was clear from the analysis that many registered customers relapse into inactivity when they find it either impossible or too intimidating to make transactions. Customers cannot transact during system downtime, or in the case of absent or illiquid agents, and feel intimidated by the risks of sending money to a wrong number, or losing or compromising their PIN. Other customers choose to protect themselves by using over-the-counter (OTC) services in preference to registering or keeping money in their mobile money wallets. All these limit the use and potential of digital financial services.

Furthermore, given the importance of word of mouth, which MSC estimates drives around 60% of decision-making on the adoption of financial services, bad experiences spread quickly in rural communities—amplifying the erosion of trust. In the words of one customer, “We keep hearing mobile money users complaining about unstable network, delayed service, missing money, and many other negative comments about mobile money. Why then should we register for these services?”

This lack of trust represents a real and expensive problem for providers. The GSMA 2018 State of the Industry Report notes, “34.5% of the world’s registered accounts are now active [90 days]”. Or, put another way, only one in three of digital financial services accounts opened are used to conduct more than one transaction in three months. Given the cost of customer acquisition, one cannot help but think that investments to improve trust in digital financial services would make economic sense.

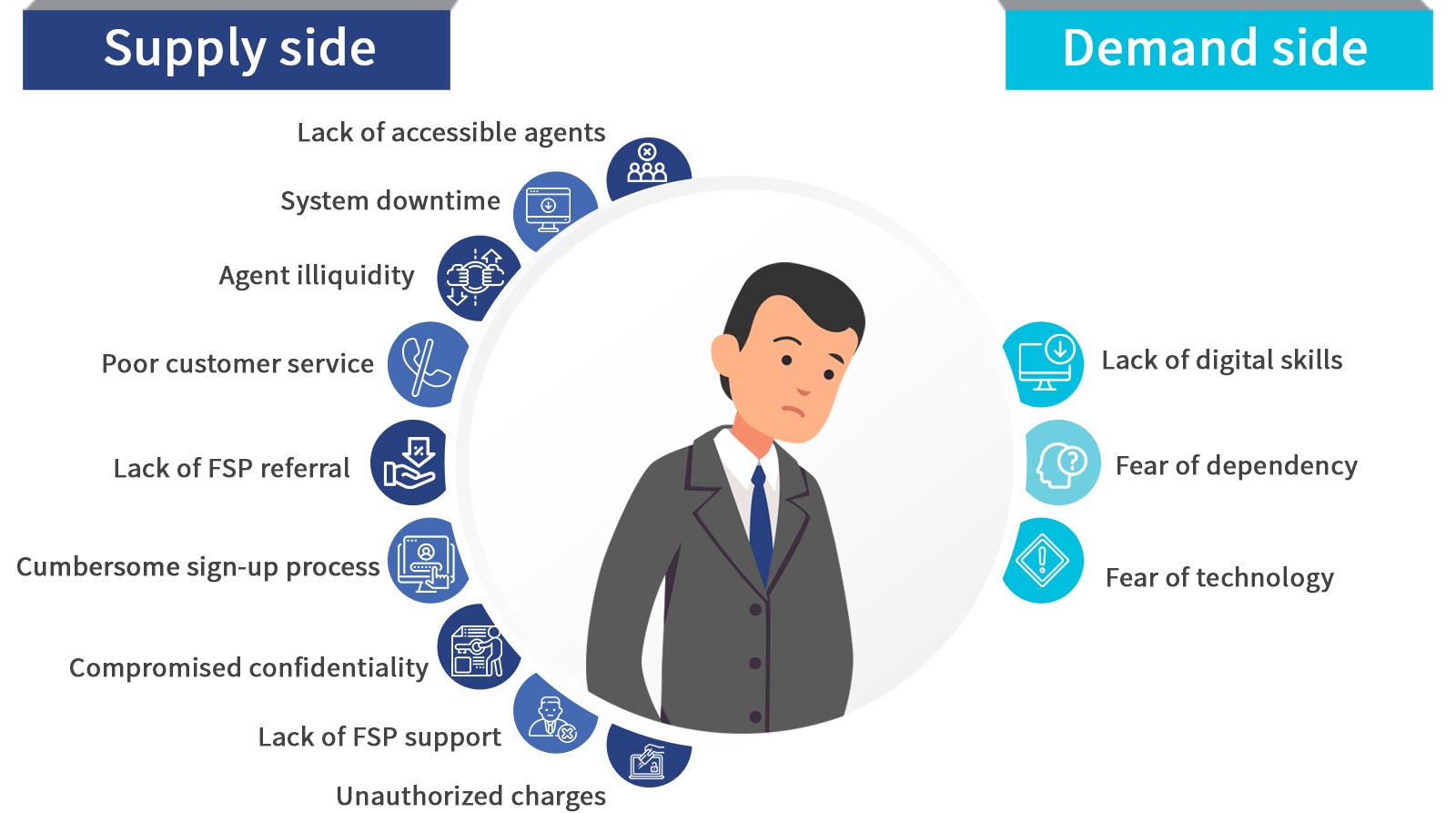

So what are the dirty dozen trust busters?

Supply side:

- Lack of accessible agents: when there are too few accessible cash-in or cash-out agents to provide credible access to basic services. In many markets this is driven by agent closures and churn, which can leave customers without access to their money. In some countries, this access is a question of opening hours, for example, in Zambia and Kenya, where most agents only work the hours and days that bank branches do. Customers in these geographies are unable to find agents to serve their transactions on weekends or after 5 pm.

- Service or system downtime: when technological issues mean that users are unable to access their funds or transact. Agents often use this as an excuse not transact when they face liquidity issues.

- Agent illiquidity: when agents lack enough e-money or cash to make cash-in or cash-out transactions. Customers find it difficult to trust an agent who is frequently unable to conduct transactions.

- Poor customer service: when agents are provided limited training and thus their ability to conduct transactions, explain products, or manage customer complaints is compromised. Poor or nonexistent agent and customer support through call centers can worsen the problem.

- Lack of referral from the FSP: when the local branch does not refer customers to agents—this is seen as a sign that they are not sanctioned or to be trusted. In some instances, where branch staff fear a loss of jobs, we have seen branches undermining agents by saying that people should carry out transactions at the branch where it safer and cheaper.

- Cumbersome sign-up process: when sign-up and know your customer (KYC) procedures are complex, convoluted, and time-consuming. Potential users, particularly those new to digital financial services, will often simply give up and not complete the registration process. When agents help with the sign-up and are apparently unable to make it quick and easy, trust is compromised.

- Compromised confidentiality: everyone, not just those who depend on agent assistance, wants confidentiality in their financial transactions. As we have seen in India and elsewhere, customers often do not consider a hyper-local agent based in the same village as desirable for exactly this reason.

- Lack of support from the financial service provider (FSP): when the FSP does not provide: 1. marketing support for the agent network to enhance its credibility and/or 2. monitoring of agents either directly, or through third party representatives commissioned to monitor and support the agent network.

- Unauthorized charges: when agents charge additional amounts for transactions, as is now common across the globe.

Demand side:

- Lack of digital skills: when potential users lack the knowledge or capability to use digital interfaces on their own. This is, unsurprisingly, more common among the oral segment for whom no intuitive interfaces have been rolled out.

- Fear of technology: when potential users lack understanding of the technology, which makes them afraid of losing funds by making the wrong keystrokes or because funds “disappear”.

- Fear of dependency: when users are dependent on agents for assistance, thus compromising confidentiality and increasing vulnerability to unauthorized charges or even fraud by agents.

Leave comments

Rajvinder Singh

25 Feb, 2020

Interesting and detailed study in this segment , insights on secrecy from local kiryana stores will surely help people in industry to look for alternatives.

Joel Patenaude

21 Feb, 2020

Terrific summary of the many issues with agents. To my mind what is lacking is elegance. Some of these solutions have a Rube Goldberg feel to them. I think the way forward is to eliminate the agent. Most in this industry agree theirs is a temporary role, deemed necessary to grow adoption, especially for those who are poor and less comfortable with technology. So let's improve the technology, not force adoption of not-ready-for-primetime technology, especially when it adds costs to the consumer. Two areas of promising tech I'd like to see a ton of resources put into are numeracy (Brett Matthews of My Oral Village is a lone voice) and CBDC/White Space (The Bahamas is pioneering this work). Thanks.

Joel Patenaude

21 Feb, 2020

Terrific summary of the many issues with agents. To my mind what is lacking is elegance. Some of these solutions have a Rube Goldberg feel to them. I think the way forward is to eliminate the agent. Most in this industry agree theirs is a temporary role, deemed necessary to grow adoption, especially for those who are poor and less comfortable with technology. So let's improve the technology, not force adoption of not-ready-for-primetime technology, especially when it adds costs to the consumer. Two areas of promising tech I'd like to see a ton of resources put into are numeracy (Brett Matthews of My Oral Village is a lone voice) and CBDC/White Space (The Bahamas is pioneering this work). Thanks.

Nivedita Nayak

19 Feb, 2020

A detailed report with some very useful inputs. Please keep coming out with such good reports! One successful agent scheme I remember is the Pigmy Collection Scheme run by Syndicate Bank, it was very popular in South - Western Karnataka.

Nivedita Nayak

19 Feb, 2020

A detailed report with some very useful inputs. Please keep coming out with such good reports! One successful agent scheme I remember is the Pigmy Collection Scheme run by Syndicate Bank, it was very popular in South - Western Karnataka.

by

by  Feb 18, 2020

Feb 18, 2020 7 min

7 min

Comments (5)