The power of unified digital agricultural services

by Elizabeth Berthe and Puneet Chopra

Jul 14, 2020

8 min

Digital agricultural services are gaining ground globally and transforming agriculture for smallholder cultivators. The unification of these largely unintegrated services offers a stronger proposition for actors in agricultural ecosystems. This blog explores how the journey of unification can be started and the opportunities it offers stakeholders.

The number of farmers in Africa who have subscribed to agricultural digital services has grown by between 40% and 45% per year in the past three years. According to the African Development Bank (AfDB), an estimated 33 million people in Africa have already registered for digital agricultural services, such as weather updates and market linkages. These farmers constitute nearly 13% of all the smallholders and pastoralists in Sub-Saharan Africa. Today, they find value from a range of digital agricultural services available to them.

Through digital services and platforms, the transformation of the agricultural sector and its economics is increasingly becoming feasible. This is due to innovations in affordable technologies and mobile-based solutions, which continue to expand. However, most digital agricultural platforms provide only a few services that are core to the business models of the providers. Most platforms have a “walled-garden” approach and do not provide complementing services from other synergistic platforms. This offers a huge untapped opportunity to create unified and interoperable platforms that can provide a wider range of services needed by smallholders.

Digital agricultural services can be valuable in multiple ways to the cultivating smallholders and a range of other stakeholders in the agriculture sector. For smallholders, digital agricultural services can:

- Provide easy, timely, relatively accurate, and low-cost access to information or advisory services. This access helps smallholders enhance the efficiency of their livelihood activities and mitigate risks from weather uncertainties and climate change.

- Open up possibilities for smallholders to procure agri and farm inputs, such as seeds, chemicals, fertilizer, and farm equipment. Moreover, the inputs procured through established digital means, can be of better quality, sourced conveniently, timely, and potentially at lower prices compared to traditional channels of agro-dealers and retailers.

- Provide support through better visibility to market prices and demand, and realize better prices by marketing the produce more widely and efficiently.

- Open up new opportunities and frontiers, such as digital payments, credit and insurance, and derivative trading of produce.

- Provide market-driven new income-generating opportunities, such as value addition, primary processing, and so on.

Digital agricultural platforms are useful for the providers of agri services and products in the following ways:

- Through demand aggregation, the platforms can collect and communicate the needs and preferences of farmers easily to plan sourcing and supply of agri inputs. Input suppliers can understand the nuances of demand, which can help providers to develop robust supply chain management plans. They can understand the needs, constraints, and preferences of farmers better to provide them with personalized services.

- As the models and platforms evolve, they can integrate supply chains to enable better information sharing between providers, processors, distributors, retailers, consumers, and supporting sectors.

- Providers across value chains can use the platforms to gain a more accurate understanding of the needs of the farmers. They can utilize Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) tools to align their offerings and services according to the expectations and aspirations of farmers.

- Financial service providers can utilize data and analytics to provide relevant financial products and services. They can then use the data generated through digital agriculture services to improve their decision-making. Through the platforms, financial service providers can access more data points to develop robust credit-scoring models. This, in turn, can improve the efficiency of financial transactions and introduce greater transparency in pricing.

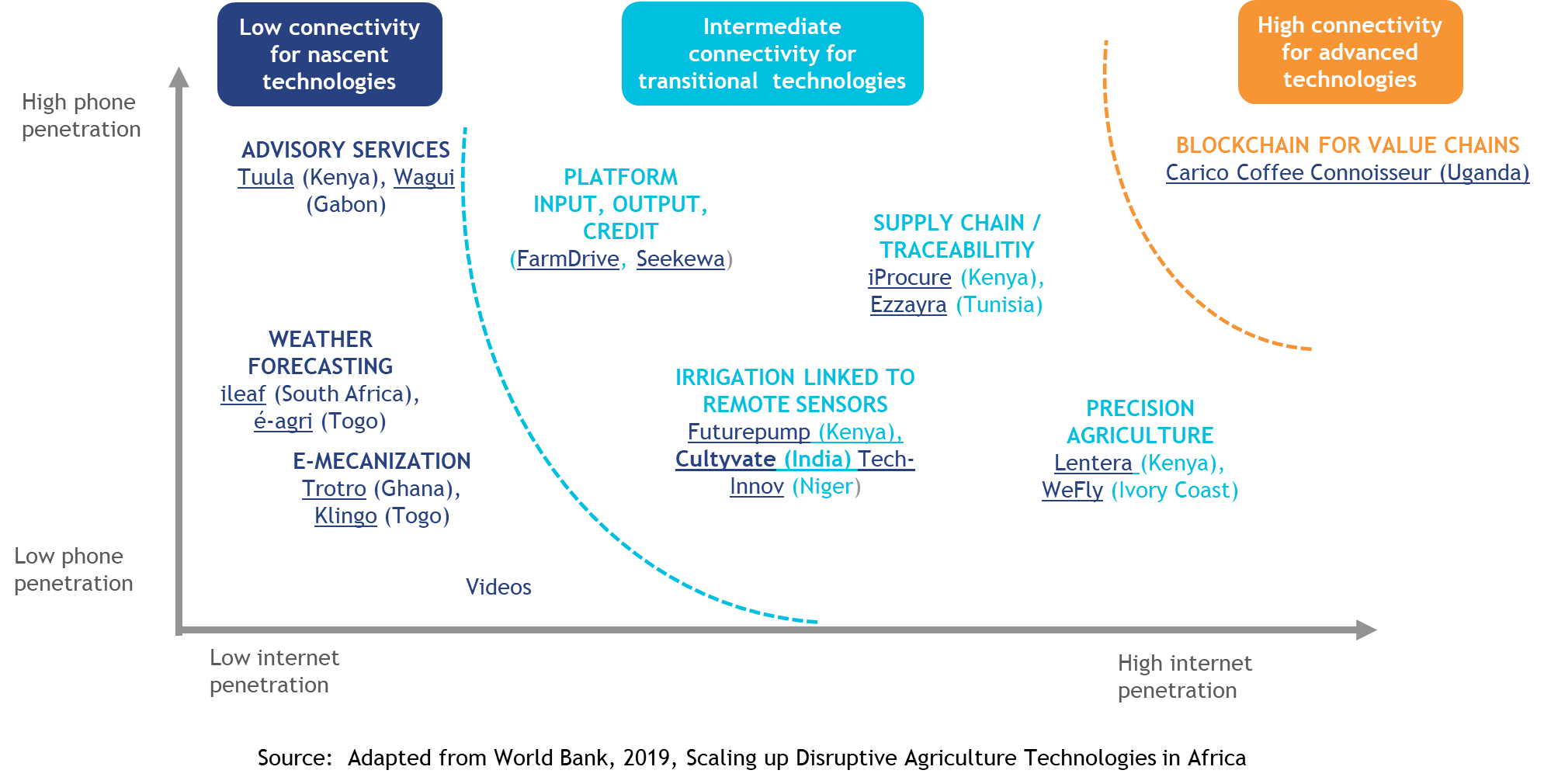

Kenya and India have been leading in the digitization of agricultural ecosystems among the developing countries in Africa and Asia. A broad range of digital agricultural services has either been evolving or is now available. These services depend on the levels of phone penetration and access, as well as high-speed internet availability and access. The graphic below examines this in detail.

The most basic of services provided through digital platforms are weather forecasts and advisories. The accuracy of these forecasts is critical for the recipients. Even minor discrepancies can lead to disastrous consequences. For example, in rain fed-areas or places with water scarcity, farmers irrigate crops based on expected rainfall. If the rainfall forecast is off-the-mark, they can end up flooding the fields or irrigating too little. These errors can destroy harvest-ready crops and risk their entire earnings in a season.

Therefore, many innovators, such as Skymetweather and ileaf are increasingly relying on local weather stations or Internet of Things (IoT) sensors located on the field to predict critical weather parameters as precisely as technology allows them to do. This is critical to building trust in and utility of the information and advisory services provided to the service recipients. In turn, it would enable such platforms to sustain membership and use of its services.

Precision agriculture tools are being used effectively to collect and analyze productivity levels alongside environmental and soil quality variables. This analysis enables service providers to recommend targeted actions to farmers. It can help them take precise actions to realize higher productivity levels or to prevent disease and pest infestation. For example, they can apply appropriate doses of nutrients, select an appropriate mix of fertilizers or chemicals, and maintain the required water levels and temperature of their crops.

Several Agritech firms offer precision agricultural tools based on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Deep Learning (DL) solutions. They collect data through drones, IoT sensors, or satellite images or a combination of all three sources. These firms provide strategic solutions to improve productivity, efficient use of resources, enhanced risk forecasting, management capabilities, and so on. The ability to access precise data can increase profits and inform the process of making credit decisions.

An intervention in Mozambique enabled extension workers to use low-cost drones to provide advice to farmers. It has helped farmers make informed decisions to improve water efficiency and crop yields. Similarly, the Third Eye project uses recreational drones equipped with near-infrared sensors and tailored software to capture and analyze data locally. Data gathered during project implementation indicates that crop production had increased by 41%, while the total use of water reduced by 9%, resulting in a 55% increase in water productivity.

Most extant platforms focus on providing only a handful of use-cases, such as advisory services, the supply of inputs, digital credit, or selective captive buying. This is a major downside of their approach. Moreover, the platforms often offer each of these services piecemeal and not as a basket of multiple services to farmers.

This offers an important opportunity for providers to integrate multiple services on a unified platform to make them more powerful. These services can include financial services, input demand aggregation and delivery, output (production) estimation and market linkages with multiple buyers, and digital payments, among others. Such integration would be immensely useful to farmers and providers. An integrated agri-platform approach can enable providers to add multiple new and relevant services, leveraging demographic and transaction data, and creating synergies with other providers on the platform.

Digital agricultural platforms can transform the agricultural sector but it will be essential to pay attention to the digital divide. Platforms must be designed to be inclusive for female farmers and for segments that enjoy limited or no access to digital tools or are unable to use them.

In some countries, the digital databases of governments capture vital farmer demographic and transactional information that covers a wide range of important parameters. These databases have been evolving to become mature and robust. One of the largest examples is the Prime Minister Fasal Bima Yojana (PM Agri insurance) and the integrated Mobile Fertilizer Management System (mFMS) in India. Individually, these databases serve varying purposes. However, unifying these databases to draw insights from across them could be immensely valuable. MSC and the Indian government’s policy think-tank NITI-Aayog are in discussions to explore the architecture and roadmap to achieve this.

Access to credit remains the biggest barrier to the sustainability of smallholder farmers. Digital agricultural platforms can have a critical role to enable access to credit. It can address several of the barriers that currently limit the availability of credit. Banks are risk-averse to work with farmers due to the limited availability of financial information around them. Digitized data can provide digital footprints in the form of sales records and purchases to determine the capacity to repay loans. Individual farmer profiles, social data, agronomic data, economic, and transaction data can be utilized to make credit-scoring algorithms more robust.

Agribusinesses already collect much of the information that banks require for credit assessments. A growing number of farmers are using mobile phones for financial transactions. These methods can enable financial institutions to undertake appraisals, conduct credit scoring, and take better lending decisions.

Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB) introduced a mobile-based platform for smallholder farmers called MobiGrow. It receives support from the MasterCard Foundation. The platform is accessible to over two million farmers in Kenya and Rwanda, who avail loans, savings, insurance, and agribusiness training opportunities. In its first year of operations, it registered over 400,000 farmers and saw transactions worth USD 22.4 million being conducted.

Bundled financial services can contribute to the scaling of the platforms. Providers can enable a wider range of financial services for the users, utilizing digital data trails, and combining access to agricultural information with financial services. The ease and the amount of data that can be collected for farmers will increase as the cost of digital tools continues to decline.

FarmDrive runs a credit-scoring system by using agronomic data, satellite data, and social data to link-local financial institutions to lend to eligible farmers. Impact Terra is a digital agricultural platform in Myanmar that bundles services as well. Its Golden Paddy platform reaches 2.8 million unique users and offers relevant information on best practices, weather, pricing information, and access to buyers, suppliers, and financial institutions.

A unified digital agricultural platform requires collaboration between multiple actors with complementary expertise. An open and shared data platform approach can be even more compelling, as this approach would offer significant upsides. These include: reduced and shared costs; ability to spread risks and bring innovations to market collaboratively and more quickly; mutually beneficial solutions, such as unified loyalty programs on the platform; ability to achieve scale and volumes rapidly; and to engage and provide support to governments. However, this also requires a much greater willingness on the part of providers to collaborate and share data and resources.

Innovative forward-looking providers, that realize the power and the value of unified services, can take a lead and the first steps to unify digital agricultural service. Philanthropic funding can provide a much needed initial support for proofs-of-concept and early demonstration of unified services, to catalyze crowding-in of additional investments for scale-up efforts.

An abridged version of the blog was first published on Soko Directory on 20th of May, 2020

Written by

Elizabeth Berthe

Partner

by

by  Jul 14, 2020

Jul 14, 2020 8 min

8 min

Leave comments