Smallholder farmers worldwide are on a perilous journey amid climate change—where are they headed?

by Monica Dutta, Aakash Mehrotra, Lakshay Jain, Chinmay Dabhade, Graham Wright and Shrutkirti Dhumal

Jul 20, 2023

6 min

The blog highlights the increasing pressure on smallholder farmers due to climate change, as they strive to build resilience and adapt to climate events. This journey is filled with challenges and is not a straightforward path. Nevertheless, there is hope in transformative agricultural technologies that can positively impact the agri-food systems, where smallholder farmers hold a crucial role. The main obstacle lies in promoting and supporting the adoption of these technologies among farmers to aid them in their journey towards sustainability and climate resilience.

“I have never seen such heatwaves in April in Mastung, nor such massive floods in my lifetime. It rained continuously for more than 120 hours in some areas. This much water seems unreal. It has washed away all we had.” (Baloch & Taylor, 2022)

I. Introduction

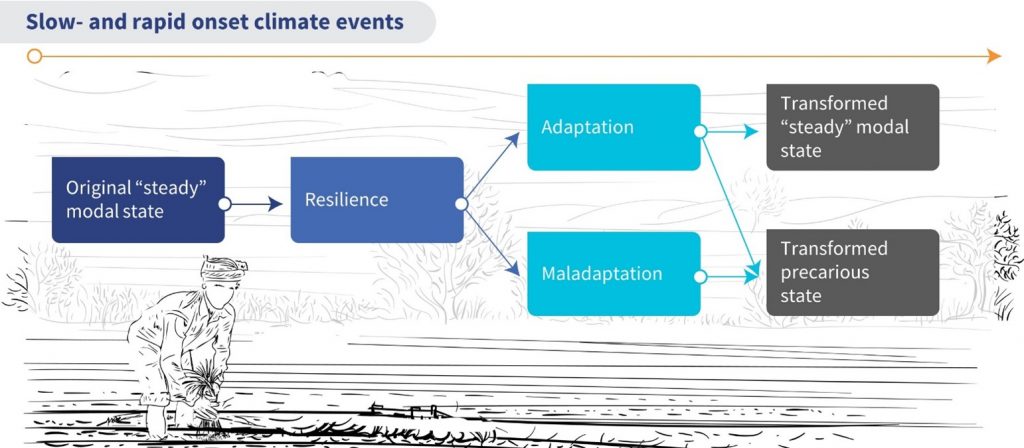

The literature on climate change typically differentiates between slow- and rapid-onset climate events. But climate change events have become progressively more regular and extreme, so the distinction is increasingly irrelevant. Smallholder farmers worldwide bear the brunt of these changes, often facing drought and excess rainfall within a single season. MSC’s work on climate change’s impact on agriculture in Bangladesh, India, and across Africa highlights how farmers’ incomes and assets are being eroded.

If we expect to contribute meaningfully to mitigate this global trend, we must understand the challenges facing smallholder farmers. We must explore the pressures smallholder farmers struggle with and their perilous journeys to build resilience, adapt, and transform their livelihoods.

II. Original “steady” modal state

“We have experienced drought before, but now it is happening almost every year. In the past, we at least had some grain stored from better yield years and got by with it. But these past few years, the yield has been consistently poor. I do not know how we are going to survive the coming winter.” (Onta & Resurreccion, 2011).

Smallholder farmers have nurtured land, crops, and livestock for millennia to earn a living. Those who have small parcels of land and who can invest in agricultural production could make ends meet. These farmers managed the somewhat unpredictable and interlinked cycles with indigenous knowledge and experience. They could usually tide over seasons when pests or diseases attacked, or the weather was unkind. They provide a third of the world’s food. Yet 40% of these farmers continue to live on less than USD 2 a day.

However, as climate change distorts and amplifies weather patterns, smallholder farmers’ ability to manage is increasingly under threat as the deviations from the mode increase. In response, farmers have to build resilience, adapt or transform. Their journey is underway.

For this blog, we adapt LSE’s 2022 definition of resilience. LSE defines resilience as the capacity to prepare for, respond to, and recover from stresses, shocks, and lifecycle events, including hazardous climatic impacts, while minimizing damage to household consumption, societal well-being, the economy, and the environment. IPCC, 2019

However, in 2014 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defined “incremental adaptation” as “actions where the central aim is to maintain the essence and integrity of the existing technological, institutional, governance, and value systems, such as through adjustments to cropping systems via new varieties, changing planting times, or using more efficient irrigation”. They contrasted this with “transformative adaptation”, an approach that “seeks to change the fundamental attributes of systems in response to actual or expected climate change and its effects, often at a scale and ambition greater than incremental activities”. So we might see IPCC’s incremental adaptation as resilience.

esilience tends to be more reactive, while adaptation is more proactive and anticipatory, as it involves planning and preparing for future climate impacts. That said, drawing a clear distinction between resilience and adaptation—and, indeed, development—is difficult. Many approaches to enhancing resilience can be and often are implemented as adaptation measures, as we will see in the discussion below. And as McGray et al. of the World Resources Institute noted in 2007, “Rarely do adaptation efforts entail activities not found in the development “toolbox.””

“Adaptation is sometimes seen as being part of resilience. Resilience capacity is described as a combination of: (i) shock absorbing and coping; (ii) evolving and adapting; and (iii) transforming. By this definition, coping is the first and ideal strategy for managing risk. However, when societies exceed their ability to cope, they should be able to adapt to the adverse changes they face” – LSE, 2022.

III. Resilience

Technologies to help farmers enhance their resilience are widely available. These include flood- and drought-resistant seeds, water, and soil conservation techniques, agro-forestry, community-based collaboration, climate information services, and several financial services, including weather-based insurance. In many countries already impacted by climate change, a growing number of farmers are using these approaches to begin to adapt and build resilience.

IV. Adaptation

“Estimated adaptation costs in developing countries could reach $300 billion every year by 2030. Right now, only 21 per cent of climate finance provided by wealthier countries to assist developing nations goes towards adaptation and resilience, about $16.8 billion a year.” – United Nations (accessed April 2023)

Adaptation involves smallholder farmers making significant adjustments to their farming practices and livelihood strategies. Many are similar to, and/or are extensions of the resilience strategies described above. Others require more extensive changes, such as building shelters for livestock to protect them from the sun and excess heat, raising housing and seedling or vegetable beds above flood water levels, or changing from rice to shrimp production in the face of the salination of soil. These require substantially more capital investment than most measures to enhance resilience, and few financial service providers are willing to offer the loan sizes and tenors needed for adaptation. Other examples of adaptation include diversifying income sources to include non-farm activities and the temporary or permanent migration of family members.

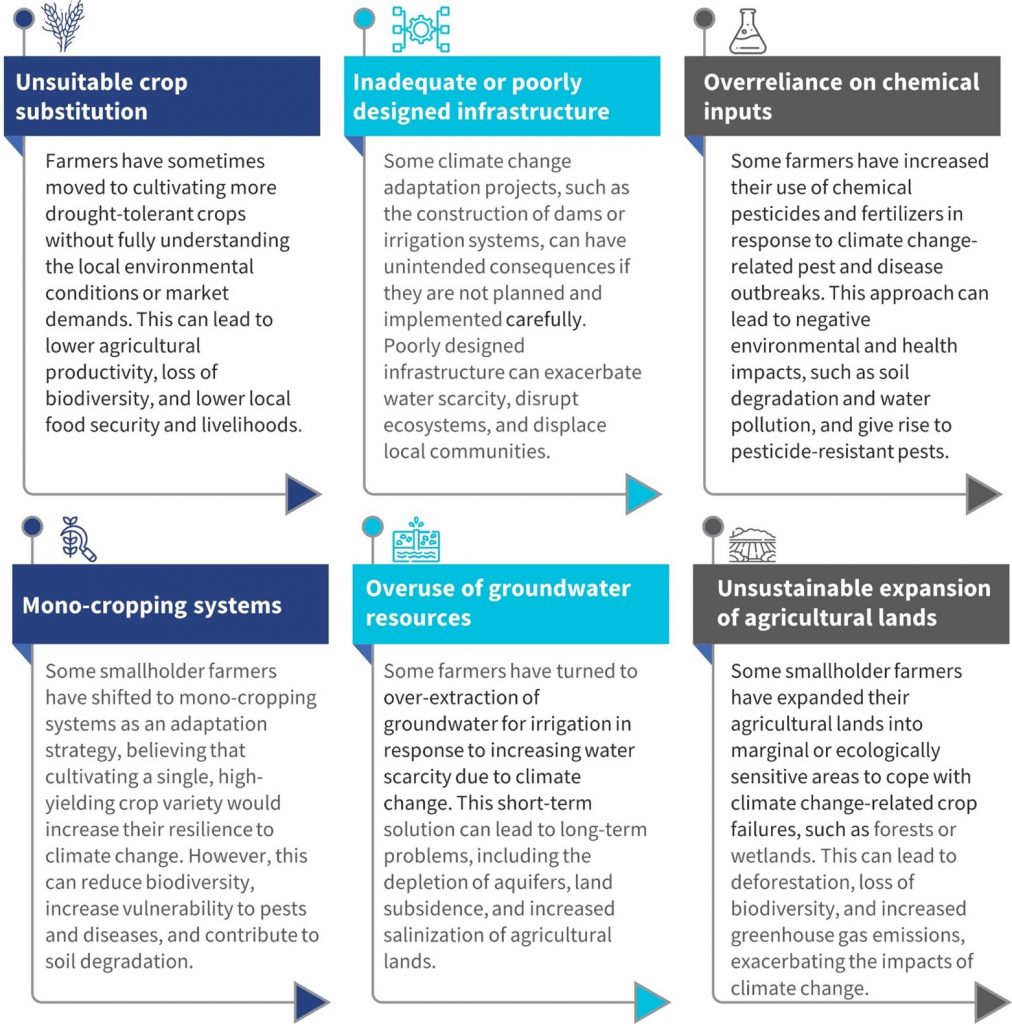

However, as farmers make these substantial changes, they also risk maladaptation. They often end up prioritizing short-term gains and quick-fix solutions. Such misplaced priorities can lead to increased vulnerability and reduced adaptive capacity in the face of evolving climate risks.

V. Maladaptation

“Most of our youth and able-bodied men migrate to the south to look for employment opportunities. Many do not return at the start of the farming season, which affects the availability of farm labor. In turn, the unavailability of labor affects farm operations and crop yield, which has implications for food security in this community.” (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2022).

Maladaptation implies actions or strategies that may inadvertently increase vulnerability to climate change or undermine a farming system’s long-term sustainability. MSC has seen common examples in its work, which include the overuse of fertilizers and pesticides in response to declining soil health or climate change-induced crop diseases. The diagram below outlines other common maladaptation practices.

VI. Positive “steady” modal state transformation

In an ideal world, adaptation should lead to a sustainable steady, modal-state transformation. Such transformation would provide smallholder farmers with long-term climate resilience, enable them to manage the vagaries of the weather, earn an improved and reliable income, and thus secure the family’s livelihood and future. As co-convener of the CIFAR Alliance’s Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRAg) working group, MSC works with various players to identify and enhance digital technology’s role to transform agri-food systems across Africa and Asia. Yet for many farmers, this positive transformation is elusive—not least of all because the vagaries of the weather are increasingly extreme, and the “panarchy” cycles are becoming more unpredictable and unruly.

VII. Negative precarious state transformation

“We are here for three generations. How can we migrate, leaving our land, property, and generations-long memories?” (Ahmed et al., 2021)

The alternative, less positive outcome is where the smallholder farmer and their family are forced to abandon farming altogether, typically after a remorseless downward slope of income and asset depletion. They then often migrate to live in squalor in urban slums as a last resort (Kugelmann, 2020 and Chung, 2022).

VIII. Conclusion

A growing proportion of smallholder farmers are under immense pressure from climate change and being forced on a perilous journey as they try to build resilience, adapt or transform to manage climate events. This journey is not linear but fraught with challenges. However, we have the technologies to positively transform the agri-food systems within which smallholder farmers play such an important role. The challenge is how we can encourage and support farmers to adopt and use these technologies along their journey.

by

by  Jul 20, 2023

Jul 20, 2023 6 min

6 min

Leave comments