In the this series, we discussed the evolution of rural housing programs in India and the most recent incarnation, Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana- Gramin (PMAY-G). We also assessed the scheme’s performance to date and suggested improvements to its design, implementation, and monitoring when compared to its predecessor, Indira Awaas Yojana (IAY). This blog discusses the existing challenges PMAY-G faces, both on the demand and supply sides as revealed by our primary and secondary research, and recommends measures to enhance its overall effectiveness.

Challenges to PMAY-G

- Supply-side challenges

The MSC team’s interactions with stakeholders including those at the block[1] and the gram panchayat[2]levels, as well as a review of existing literature, revealed several supply-side obstacles as discussed in detail below.

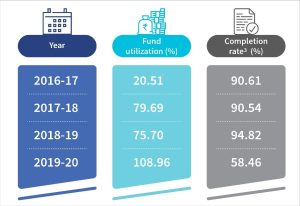

- Inadequate release and utilization of funds: The Government of India (GoI) and state governments have made profile announcements of generous allocation of funds. However, a limited proportion of the announced funds have actually been released for the program. The GoI released 58.56% (INR 272.98 billion or USD 3.9 billion[3]) of the allocated PMAY-G funds; while state governments released only 5.7% of this allocation for the fiscal year 2019-20, which translates to INR 15.63 billion or USD 220 million.

The over-allocation of funds coupled with insufficient release hurts the government’s ability to complete the targets established for the year within that same year. Although the overall target achievement under the scheme in the initial three years is more than 90%, this is primarily because of the accounting method used (see footnote 3). The actual physical progress during the respective years has remained slow—as can be seen from the rate of completion in 2019-20.

The over-allocation of funds coupled with insufficient release hurts the government’s ability to complete the targets established for the year within that same year. Although the overall target achievement under the scheme in the initial three years is more than 90%, this is primarily because of the accounting method used (see footnote 3). The actual physical progress during the respective years has remained slow—as can be seen from the rate of completion in 2019-20. - Convergence with other schemes: For convergence with the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) and Swacch Bharat Mission-Gramin (SBM-G), the AwaasSoft captures beneficiary-specific information, which includes the job card number for MGNREGS and the SBM-G number during the beneficiary registration process. This has led to better convergence with these schemes. The scheme guidelines do not specify the requisite steps for convergence with other schemes. As a result, many beneficiaries cannot avail of the convergence benefits,[4] such as electricity connections, gas connections, and piped drinking water.

- Minimal scheme awareness: Awareness regarding the guidelines, benefits, and conditionality of the scheme is minimal among supply-side stakeholders at the village level including the gram panchayat and the Panchayat [5] Furthermore, due to complex scheme guidelines, some banking institutions lack clarity on their role in the provision of housing credit facilities to PMAY-G beneficiaries. As a result, scheme details are not communicated properly to beneficiaries.

2) Demand-side challenges

Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with PMAY-G beneficiaries, coupled with a review of the existing literature revealed challenges that demand-side stakeholders, namely, beneficiaries face. We discuss this in detail below.

- Fund insufficiency: The quantum of assistance provided under the scheme, that is, INR 120,000 (USD 1,720), was determined in 2016 upon the scheme’s inception. The scheme design does not account for inflation in material and labor costs over the years.[6] Beneficiaries felt that home design and quality as specified by the scheme guidelines are not attainable at current market prices of material and labor. This results in compromises in construction quality and additional expenditures for beneficiaries.

- Delay in disbursement of installments: Instalment payments[7] under the scheme are linked to the level of completion of construction and are processed once a real-time verification report is submitted through the AwaasApp. Delays in physical verification of completed construction, which block-level officials and gram panchayat representatives carry out, lead to delays in disbursement of funds. Disbursements are often delayed even when timely physical verification occurs because the signatories have not signed off on the Fund Transfer Order (FTO).[8]

- Non-receipt or delay in convergence payments: Beneficiaries receive convergence payments over and above the assistance provided under the PMAY-G scheme. The convergence benefit is approximately INR 18,000 (USD 260) for MGNREGS and INR 12,000 (USD 170) for SBM-G, which, together, increases the overall assistance amount by 20%. Interaction with the beneficiaries revealed instances of delay or non-receipt of convergence payments. This renders the purpose of convergence futile, as beneficiaries do not receive benefits during the construction phase.

- Exclusion error from Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC): PMAY-G has stringent guidelines to identify and select beneficiaries based on SECC data. However, this data was collected in 2011 and thus proved to be often out of date. Beneficiaries are often unaware of the existing guidelines or have limited information about the identification and selection processes. Beneficiaries who are excluded from the SECC database, which is a precondition for scheme eligibility, are not aware of the option to enroll manually. In general, the enrolment process remains opaque for beneficiaries.

Recommendations and way forward

Based on MSC’s research, we suggest the following enhancements at the policy and operational levels that focus primarily on scheme design and implementation:

i) Policy-level recommendations

Streamline the funding: The GoI and state governments should develop a mechanism to release funds as per budget allocations and ensure timely disbursement to beneficiaries. Delays in the release of allotted funds and disbursements to beneficiaries escalate the time and cost involved in the process of constructing a house.

The solution to this is twofold. First, the GoI and state governments should implement just-in-time funding through a treasury single account so that money is replenished for spending on a near real-time basis without creating float in the system.

Second, state governments should implement smart or automated payments by doing away with multiple signatories to the FTOs to release funds to the beneficiaries. This can be achieved by introducing automated approval of the geotagged images captured during the physical inspection of the level of completion.

- Account for inflation in the assistance amount: The GoI should account for inflation from the previous fiscal years and adjust the amount of assistance accordingly on an annual basis. The assistance amount can be revised based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) data released by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The inflation-adjusted dynamic assistance amount will enable beneficiaries to maintain the desired quality of construction and finish building their houses on time.

ii) Operational recommendations

- Automate the registration of beneficiaries excluded from SECC: A manual system exists for registering beneficiaries excluded from the SECC 2011 database. Under this system, the Gram Panchayat prepares and forwards the list of eligible households to the Block Development Officer (BDO).[9] The BDO has the right to recommend inclusion based on the merit of the claim and verification, after which the name(s) is added to AwaasSoft. However, this registration process has not been communicated effectively to the beneficiaries, which renders it useless.

The GoI should make changes to the MIS and enable a mechanism for online registration of such excluded beneficiaries. Besides the online system, the GoI should also run awareness campaigns at the panchayat level to effectively communicate the registration process for those who feel they have been excluded incorrectly.

- Strengthen convergence with other schemes: The current MIS does not track convergence of PMAY-G with schemes, such as PMUY, SAUBHAGYA, and NRDWP. The lack of accountability has led to poor convergence outcomes for these schemes. The GoI should suitably modify the MIS and enable a mechanism to capture beneficiary details to facilitate convergence with such schemes during beneficiary registration—as is the case with MGNREGS and SBM-G. For example, for convergence with MGNREGS, the GoI uses the MGNREGS database, that is, the job card number. Similarly, for convergence with PMUY the GoI should use the PMUY database, that is, the gas connection, LPG subscriber ID, or application number.

- Introduce an automated module for registering for inspection: The current system of monitoring and inspection is manual and follows a top-down approach. This means that beneficiaries cannot initiate inspections of the progress of their construction. The GoI should adopt a bottom-up approach and make suitable changes to the MIS.

The system should be modified suitably by introducing a USSD-based service, toll-free number, Common Service Center-based service. This would allow beneficiaries to raise requests for completion level inspection, thereby reducing the time it takes for inspections to be carried out, and hence, disbursements.

Since its inception, PMAY-G has achieved scale, which earlier housing programs had failed to accomplish. Many believe that having a home brings pride to a household, mitigates uncertainties, and frees up time for people to pursue economic activities resulting in economic and social independence. Although PMAY-G continues to help millions of Indians realize their dream of owning a home and receive other necessities, several hurdles remain before all homeless rural Indians can build a house they call their own.

[1] Based on the administrative structure, a block is a district subdivision consisting of a cluster of villages for the purpose of the Rural Development department and Panchayati raj institutions.

[2] Gram panchayats are formalized, local self-governance systems in India at the village level, which has a Sarpanch as its elected head.

[3] USD 1 = INR 70

[4] Convergence benefits include MGNREGS for labor, SBM-G for toilets, PMUY for cooking gas connections, Saubhagya for electricity connections, and NRDWP for drinking water.

[5] The Secretary of the panchayat is a non-elected representative appointed by the state government to oversee panchayat activities.

[6] Trends in prices of material and cost indices in building construction.

[7] Payments under the scheme are made in instalments (a minimum of three). Payments are linked to the level of completed construction, that is, foundation, plinth, windowsill, lintel, roof-cast, and are subject to verification.

[8] The FTO ensures leakage-proof payments and is generated against a sanctioned number of houses.

[9] The Block Development Officer is in charge of the block. The officer oversees that approved plans or programs are implemented efficiently.