On a recent field trip (one that happened before the COVID-19 outbreak), we watched in horror as four enthusiastic design consultants from a large international firm had set up a classic “sit them on school benches and tell them how to save” financial education program. The “planning sheets” to guide the poor farmers were in English. An indigenous staff member who spoke the local dialect and the national language delivered the accompanying lecture, translating from another member who spoke both the national language and English, and had learned the script from his new American paymasters.

The nature of the problem

Towards the end of my decade in Bangladesh, a growing number of immensely successful local institutions had become heartily sick of hosting international, fly-in-fly-out consultants. This was particularly true in the microfinance sector where local consultants had a much deeper understanding of the issues and on-the-ground realities. In contrast, many, if not quite all fly-in-fly-out consultants had little knowledge of the country’s history, culture, or market, institutional and political nuances, or even the language for which many were martyred in 1952. To add insult to injury, these fly-in-fly-out consultants were paid fee rates measured in many multiples of the salaries of their local counterparts.

As I noted in a previous blog, this dependence on fly-in-fly-out consultants can “lead to either inappropriate assumptions or conclusions or both, which have detrimental effects on both the development process and outcomes and leave years of experience and learning ignored and unused.”

In “The Absent Voices of Development Economics,” Arvind Subramanian and Devesh Kapur highlight how the concentration of development economics research in developed countries reflects and amplifies this problem. They note that “Development economics focuses on improving the well-being of billions of people in low-income countries, but the Global South is severely underrepresented in the field. A small number of rich-country institutions dominate, and their growing use of randomized controlled trials in research is entrenching the imbalance.”

A little history

In the 1990s, multilateral and bilateral donors responded to these very challenges. The donors pushed for programs that would train and empower local researchers and consultants and transfer skills to the management and staff of local institutions. They argued that this would lead to sustainable development rather than perpetuating the continued dependence on external researchers and consultants. Players in the sector accepted that the process would take more time but would pay off in the longer term by embedding skills in local institutions. And that was preferable to the quick-fix fly-in-fly-out solutions that often failed to understand local conditions or take them into account.

Then, at the turn of the century, the pendulum swung back and impatient, inorganic development returned to fashion. In many ways, this is understandable. How much longer must millions of people suffer just because development professionals take a longer-term view and seek to indigenize capabilities? If we can reduce the vulnerability of people through quick-fix solutions, should we not seize the opportunity now? It is a very real ethical dilemma.

The ethical dilemma

Yet implicit in the dilemma are several conditions. First, that the quick-fix solutions created by fly-in-fly-out international consultants both make sense and have the buy-in of the institutions that must then implement them. Second, that these solutions are sustainable and largely immutable irrespective of changing local conditions. Third, that the recipient institutions will pay the bucks to fly international consultants back in when they need the next round of research, strategy refresh, or operational guidance. Last, that they will be willing to do this with or without the financial backing of donor agencies.

The nature of the opportunity

The pandemic has highlighted this challenge and left many international consultants unable to fly into the countries they were meant to be advising in or visit the communities they have been researching. The world has not stopped but it has changed. With vaccines unlikely to be available at scale in Africa until 2023, international consultants are unlikely to be willing or even able to go there for years to come.

This is our opportunity to re-focus on indigenizing development and, doing so, to reduce millions of air miles for international consultants—a bonus in the fight against climate change.

The indigenization of skills

The indigenization of skills to support the development process need not compromise its impact. Indeed, if done well, indigenization is likely to better design, target, and improve development. Yet in the same way that players in the ecosystem have renewed their focus on making development gender-intentional, we will need to make all interventions indigenization-intentional. All programs, from the planning process through to dissemination, need to be clear about exactly how they will involve, train, and empower local government officials, researchers, consultants, and the industry.

For example, as is done in many cases in India, local universities and think tanks should play a leadership role to identify research issues, draft the research plan, lead in data collection and analysis, write the report, and disseminate results. This should be done in close collaboration with international academics and researchers who will provide mentorship and guidance throughout the process. In some cases, the limitations of local universities will require the development and implementation of programs designed specifically to enhance indigenous capabilities across a range of research methods, as well as critical, logical, and analytical thinking. These programs can be developed with dual objectives—to strengthen indigenous capabilities and to respond to specific research needs.

A good example of this type of initiative is Women’s Economic Empowerment and Digital Finance (WEE-DiFine), which receives funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and is housed in BRAC’s Institute of Governance and Development in Bangladesh. WEE-DiFine seeks to generate a comprehensive body of evidence that addresses the impact of digital financial services (DFS) on women’s economic empowerment and the causal mechanisms between the two by funding rigorous research across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

We need to put the era of academics from rich countries using indigenous researchers as basic data collectors behind us. The capabilities of local, indigenous consultants need to be developed and strengthened. This has always been part of our mission at MicroSave Consulting (MSC). In 2008, the project completion report on MicroSave prepared for FSD-Kenya and CGAP concluded, “By the end of the project, thirty-nine senior [local] service providers, thirty-six other consultants, nine young executive professionals and six MicroSave staff have been certified and seventy-six assignments have been completed. In addition to these certified individuals, a considerable number of individuals within Action Research Partners have acquired capacity (although not necessarily certification) through exposure to MicroSave training or other support.”

MSC remains proudly committed to this indigenized approach as we encourage and enhance south-south cooperation wherever possible to maximize the flow of experience, ideas, and capabilities within our organization. Ninety-nine percent of our staff are drawn from the countries we work in. Training local governments, researchers, and industry remains a key part of our work both through The Helix Institute and as an integral part of many of our programs and projects. This commitment to training and human capital development has led to the transformation of our partners, including Equity Bank, BURO-Bangladesh, and more than 325 other financial services providers across Asia and Africa. Our local presence and leadership and deep understanding of culture, language, and social norms allow us catalytic access to policymakers and regulators and the chance to forge partnerships with them.

We need to ensure that most, if not all, projects include a core component to ensure the transfer of skills and capabilities.

Looking to a brighter, more sustainable, future

Subramanian and Kapur conclude that “…diversity and broader representation are the best safeguards against intellectual narrowness resulting from elite capture.” This is true, but to realize this we will need to open our minds to the importance of local knowledge and understanding. We should invest in the capabilities of local researchers and consultants, and in the management of institutions.

Some of this is already underway through scholarship programs, although these are too few and far between and usually involve attending courses in rich (and expensive) countries. Now is the time to renew the pledge to support and enhance south-south cooperation, as well as more collaborative ways of working.

The pandemic gives us the opportunity and impetus to do just that—we should seize it!

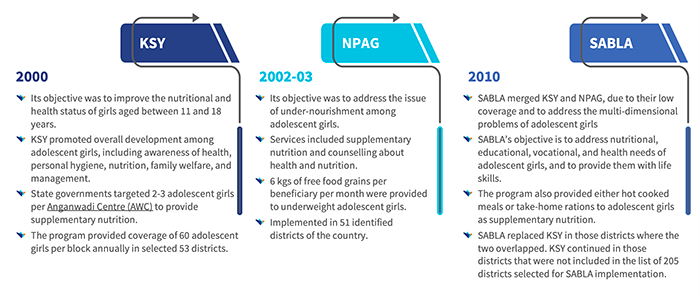

SABLA

SABLA