Background

Vaccine hesitancy can jeopardize India’s plan to defeat COVID-19 as it scrambles to vaccinate its population in the wake of the second wave of the disease. While the second wave seems to be receding, the possibility of an intense third wave looms large. The fear of a third wave is real because the rate of vaccination has been slow, the possibility of more virulent strains of the virus emerging is high, and the need to reopen economic activity is critical—though it may lead to people adopting COVID-inappropriate behavior, as seen from our studies in the past.

In this situation, the best possible solution to mitigate the risk of a third wave is to quickly vaccinate as many people as possible to break the chain of transmission and reduce fatalities. Enforcing COVID-appropriate behavior and building the capacity of the health system has to continue in parallel.

Currently, progress in vaccination has been slow because of an imbalance in supply and demand. However, as per the plans released by the Government of India, vaccine supply should normalize by July-Aug 2021. The plan is to have more than 2 billion vaccine doses by Dec, 2021, which is enough to vaccinate the eligible population. The availability of vaccines has to be complemented with a massive ramping up of the supply chain, vaccination centers, and healthcare staff to distribute and administer the vaccine. Even if availability, distribution, and administration of the vaccines are sorted, achieving complete vaccination of the eligible population by Dec, 2021 is a daunting task. And the reluctance of people to get a shot in their arms, or vaccine hesitancy, remains a key factor that can jeopardize the plan.

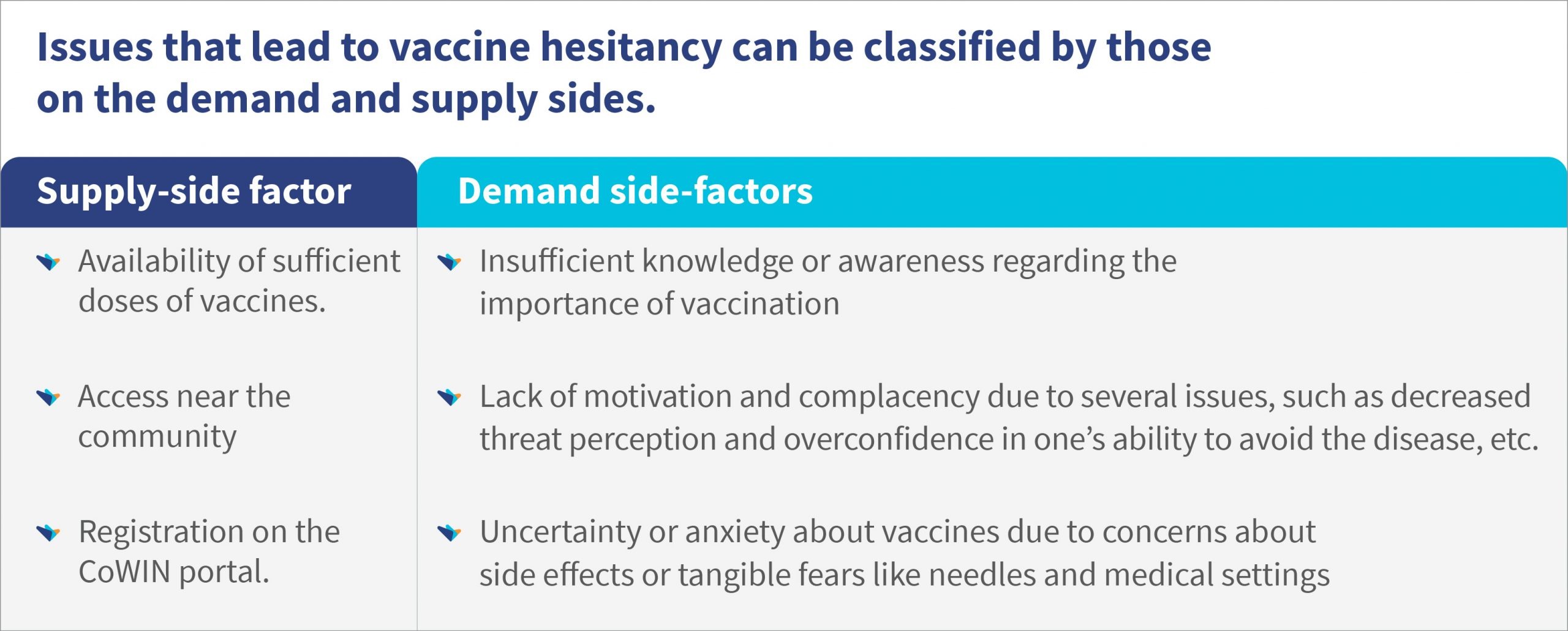

According to the World Health Organisation, vaccination hesitancy refers to the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccine services. It is influenced by factors, such as complacency, convenience, and confidence. Issues of vaccine hesitancy have already started cropping up in different parts of the country and across the world. These need to be tackled on a priority basis as misinformation and complacency can spread quickly.

For example, in the USA, the seven-day trailing average of vaccination has dropped from the peak of 3.7 million a day in mid-April to less than a million per day toward the beginning of June, 2021. About 41% of the population is fully vaccinated and 51% have received at least one dose—a large part of the population remains unvaccinated. This is primarily due to vaccine hesitancy and it is almost certain that India will face this issue as the availability increases.

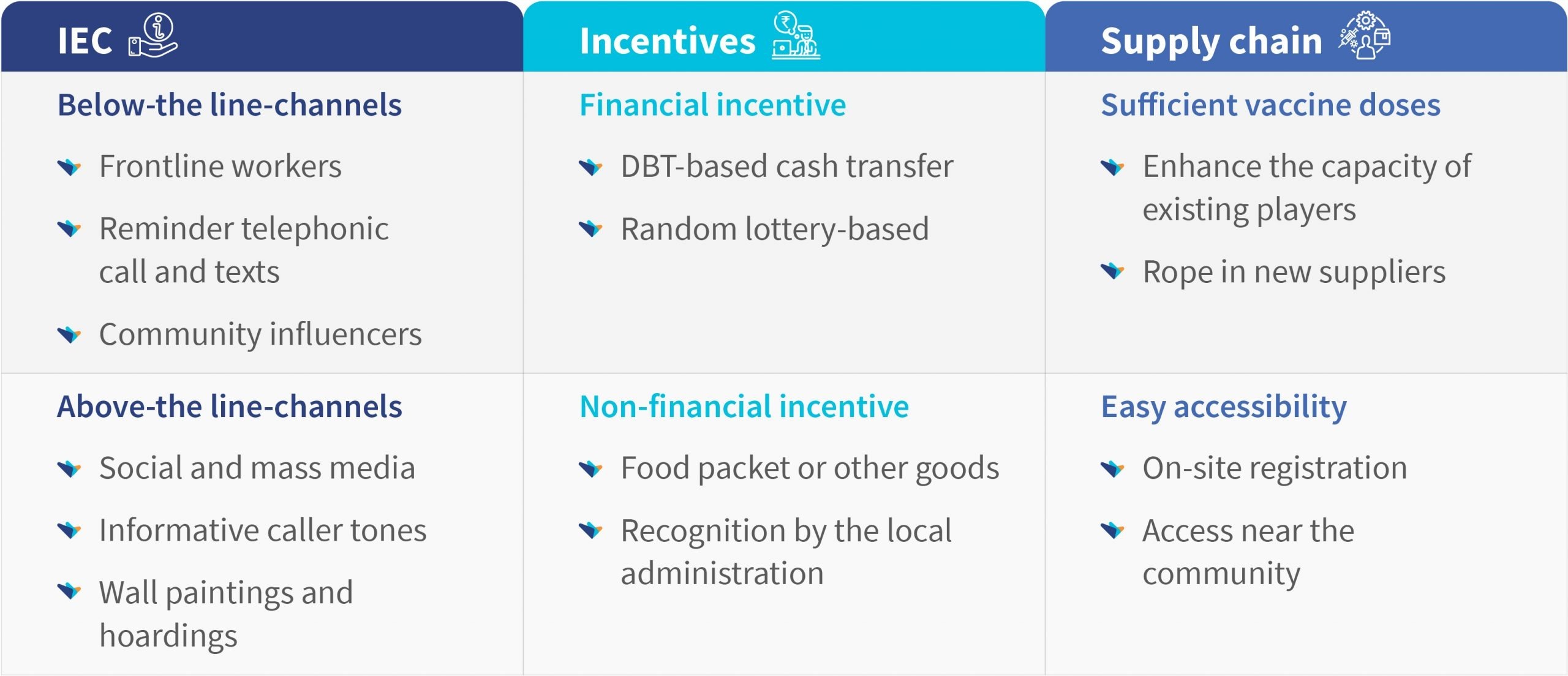

A three-pronged approach that combines interventions from both demand and supply sides is needed to manage vaccine hesitancy. Information, Education and Communication (IEC) is the most important “prong” in the approach to reduce vaccine hesitancy. It can be even more effective if coupled with the other prongs of incentives and an efficient supply chain. The following table provides a list of ideas across these three elements to manage vaccine hesitancy.

The following table provides a list of ideas across these three elements to manage vaccine hesitancy.

Information, Education and Communication (IEC)

IEC can be through below-the-line (BTL) or above-the-line (ATL) channels. The key is to ensure that all IEC campaigns are carefully planned, executed and monitored with active feedback loops to ensure that messages are adjusted and misinformation is addressed rapidly. MSC’s work on the effective communication of government to people (G2P) benefit payments provides important insights for this.

Below-the-line IEC channels

- Frontline workers: People-to-people awareness campaigns can be launched that utilize frontline workers like ASHAs, Anganwadi workers (AWWs), and auxiliary nursing midwives (ANMs). The frontline workers can either reach the eligible candidates or specific target groups directly to motivate and track them. Mechanisms for supportive supervision and monitoring may be set up.

- Last-mile service delivery points: Campaigns can also be launched through the vast networks of citizen-facing outlets developed to deliver products and services to the rural population, such as Citizen Services Centres (CSCs), Public Distribution System (PDS) dealers, fertilizer dealers, and self-help groups, among others. MGNREGA work sites can also be used for this purpose.

- Through reminders and telephone calls: Health personnel like Community Health Officers (CHOs), Block Community Process Managers (BCPMs), and ANMs may be deployed to speak to hesitant clients through phone calls to motivate and convince them to get vaccinated.

- Through community influencers: Community influences like religious and community leaders, gram pradhans, panch, and ward members, among others, may be identified and engaged with. They can play a critical role in influencing the vaccine-hesitant group.

Above-the-line IEC channels

- Regular activities that explain the importance of vaccination, its safety, efficacy, and possible side effects need to be initiated and increased. Such activities, including social media campaigns, mass media campaigns, informative caller tones particularly voiced or fronted by a famous non-controversial celebrity like sports personality or film stars, wall paintings, and hoardings could prove vital in dealing with misinformation and influencing the decisions of people to get vaccinated. A lot of action is already happening through ATL channels but it needs to increase as we vaccinate early adopters and start to target hesitant population.

Incentives

Incentives can play a key role in motivating people to take vaccines. These may be in the form of financial incentives or non-financial incentives.

- Financial incentives: One form of financial incentive can be DBT cash transfers to the households if all the eligible members get vaccinated. It can generate healthy competition among the residents of an area or community to take up vaccination.

A lottery system could also be tried where every vaccinated person is eligible for a lucky draw once that area, block, or district reaches a certain threshold of vaccination. A few big prizes can be announced to motivate people to participate in it. FLWs could also be incentivized to get their eligible catchment population vaccinated. Gram panchayats could also be incentivized to motivate people in their jurisdiction to get vaccinated.

- Non-financial incentives- Food packets or other goods can be provided if all members of a house are vaccinated. This may be a top-up to the already sanctioned quantity of ration through PDS. Another way could be by recognizing those households as “Adarsh” (ideal) houses, where all the eligible members are vaccinated. These households can be felicitated by the local administration with a certificate, sticker, badge, or similar token.

Mandatory vaccination status for non-essential events that attract attention can also be tried as positive reinforcement for vaccination. Such events include entering famous places of worship, unrestricted air/train/road travel, entry in sport stadiums, gyms, swimming pools, conducting functions like weddings, and holding political gatherings only when organizers are vaccinated, among others.

Supply chain

The availability of vaccine doses and its easy accessibility play a critical role in influencing the issues related to complacency and convenience, and in turn affect vaccine hesitancy.

Ensure sufficient doses of vaccines

As per the National Health Authority, the demand-supply gap in COVID-19 vaccines stood at 6.5:1 at the time of writing, falling from an earlier gap of 11:1. While a lot of work needs to be done to bridge this gap, a strong pipeline of potential vaccine candidates and enhanced vaccine production in the country suggest the gap is set to reduce further.

Access near the community

The government may utilize the existing Universal Immunization Programme (UIP), where ANMs conduct regular vaccination sessions at pre-designated places in the community, such as health sub-centers, Anganwadi centers, and Panchayat Bhawans. In addition, the newly developed health and wellness centers along with their staff could be utilized to augment the vaccination drive. Drive-through vaccination centers may be considered to improve access and visibility.

Registration on the CoWIN portal

People in the age group of 18-45 years have found it difficult to get registered on the CoWIN portal primarily due to two reasons—the limited availability of slots and the limited number of individuals who use phones. As per the TRAI’s press release for May, 2021, the overall teledensity of India was 85.78%, while the rural teledensity was 59.28%. The teledensity numbers for states like Bihar and UP are in stark contrast to more urbanized states like Delhi. Even those who have phones may not necessarily have smartphones and are often unfamiliar with technology. This puts a considerable proportion of the population directly at a disadvantage. Network issues also act as a deterrent. The problem of slots will be resolved once the availability of vaccine doses improves.

To give equal opportunity to all for registration, the government may consider allowing on-site registration for eligible populations. Stakeholders can also utilize alternate channels like self-help groups, PDS shops, fertilizer dealers, and common service centers apart from routine healthcare frontline workers like ASHAs, ANMs, and AWWS, among others.

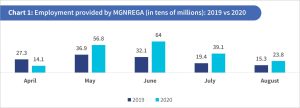

The effect of the pandemic on income and employment

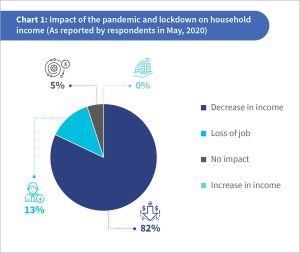

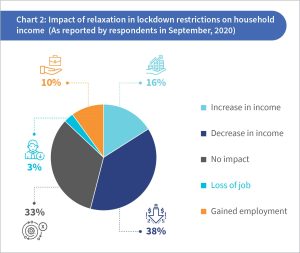

The effect of the pandemic on income and employment In September, 2020, MSC asked respondents whether they noticed any change in household income compared to the months of complete lockdown. Their responses are illustrated in Chart 2. 16% reported an increase in income while 10% said they regained employment once the lockdown restrictions were eased. This indicates that conditions had begun to return to normal.

In September, 2020, MSC asked respondents whether they noticed any change in household income compared to the months of complete lockdown. Their responses are illustrated in Chart 2. 16% reported an increase in income while 10% said they regained employment once the lockdown restrictions were eased. This indicates that conditions had begun to return to normal.