The Jakarta Post first published this blog on 8th March, 2022.

Working from home: A choice for some but a circumstance for another

Work from home (WFH) has become associated with the pandemic for those who have the luxury to choose to work from home. Yet not everyone can have this option and still have sustainable income, decent working space, and secured social protection each month. “Other” work-from-home workers have been working from home much before the pandemic but under different working circumstances.

These others are home-based workers. According to the ILO/MAMPU project report, home-based workers (HBWs) are those “who are self-employed and/or subcontracted piece-rate workers (putting-out system), and most of them are women.” In Indonesia, the law on MSMEs also accommodates the concept of home-based workers, categorizing them as an informal sector.

The Implementation Guideline to Home Industry Development, published by the Indonesian Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection (MoWECP), classifies home-based workers as a cottage industry. A cottage industry is a production system within which products are produced by creating additional value from raw materials, carried out in individual homes and not in a particular location (factory).

Yet these home-based workers, whether in the putting-out system, self-employed, or part of the cottage industry, remain vulnerable to shocks. The Indonesian Labor Law is yet to define HBWs. Indonesia has yet to ratify the ILO Convention No. 177 on homeworkers. In the absence of a law, HBWs remain predominantly informal workers. Informal workers lack formal contracts, stable income, high wages, health cover, workers’ insurance, and adequate working conditions. The absence of a law increases their vulnerability to unemployment, exploitation, and poverty.

A WIEGO 2021 Statistical Brief outlines that COVID-19 exacerbated the already-existing multiple vulnerabilities of HBWs. For those who do not use ICTs in their work, HBWs suffer the greatest loss of work and income. In Indonesia, despite the challenges, women in informal work have proven to be resilient, even though they are paid lower than men. A Jakarta Post article also mentioned that informal female workers, such as women HBWs, are expected to also take on the primary child-rearing responsibilities and housework, besides earning low wages.

Sense and workability: A facilitator’s remark on women home-based workers

In many social development programs, heroes in the field contribute to the success of a program. One such hero in this context is Zaenab Hafiezh. Zaenab is a local facilitator who supports the MoWECP’s program on women’s economic empowerment for female home-based workers in Rembang Regency (Central Java Province).

Zaenab, also an HBW, applied to be a facilitator in 2016 for MoWECP’s women home-based workers program in Rembang. The MoWECP was set to support the program for only two years, after which it would continue from the local regent office. While many of her fellow facilitators resumed their role, Zaenab was among the ones that continued her critical role as facilitator to several women HBWs in the neighborhood.

As a fellow HBW, Zaenab understands her peers’ situation, challenges, and needs in navigating livelihood strategies and securing basic everyday essentials. Zaenab facilitates women HBWs who are self-employed and in the putting-out system. Her task is to support the mobility level and empowerment of those she facilitates, according to the “implementing guideline on home-based workers” published by MoWECP.

This program was part of the ministry’s effort to achieve the 3ENDs, namely: (1) ending violence against women and children, (2) ending human trafficking, and (3) ending economic inequality between men and women.

To Zaenab, the 3ENDs goals reflect real concerns she learned from several experiences of her fellow HBWs. She also believes this women’s home-based economic empowerment program by MoWECP is a tactical approach to reducing violence, trafficking, and economic inequality in her hometown. Zaenab’s facilitation journey, though, was not smooth. She faced risks from husbands who rejected the program and blocked their wives from participating. Yet she saw other instances where this program could help survivors exit domestic violence situations. From her observation, women HBWs experience economic struggles alongside domestic violence. The burden does not stop there. Some of these women are the primary breadwinners for their families and struggle to make ends meet while caring for children and household chores.

Based on the lessons from Zaenab’s facilitation, the workability of women HBWs depends on the fulfillment of four critical needs. These are:

- Assistance in strengthening leadership and confidence as women home-based workers, to enhance eligibility and mobility;

- Support in capacity building on product development and marketing to increase the value of their work;

- Facilitating a safe space to include men in the conversation, especially husbands of women HBWs, who are also vital to support their wives;

- Commitment in policy and budgeting to recognizing and protecting home-based workers as acknowledged workers.

Zaenab notes that if the above needs are supported, the pathway to increasing female home-based workers’ mobility level, quality of employment, and economic empowerment is achievable and will help achieve the 3ENDs objectives.

The MoWECP stated that:

1. Strengthening women’s leadership and economic empowerment is part of its mandate under the gender mainstreaming unit and as part of their home-based workers’ programs. It has initiated a series of awareness campaign activities as part of this endeavor. This includes socialization on themes related to gender equality, gender-equality-based entrepreneurship, eliminating violence against women and children, and reproductive health.

The MoWECP also notes the importance of including men in conversation and awareness programs on women’s economic empowerment. It has already included partners to develop and execute more tailored programs as needed.

2. The MoWECP has also connected with some sub-national governments to promote local homeworkers’ products in local markets, through local and national crafts councils, and to affiliated companies and private sectors. The mentorship program will also serve as a platform to enhance product development and marketing capacity.

3. MoWECP supports the endeavor of several local governments that made local commitments through development planning and budget. It has also mandated its agencies on-site to be the activity focal point to support local initiatives.

Yet MoWECP realizes that it too will need collaborative support from allies to achieve the needs of women home-based workers comprehensively.

Friends, allies, and comrades

So, who are these allies of women home-based workers in Indonesia who can fulfill the said needs? Moreover, how can more players support their empowerment pathway?

The MoWECP has been a friend, ally, and comrade to women home-based workers by initiating the women’s home-based economic empowerment program since 2016. MoWECP has organized a pilot program in 21 regencies and cities. It is now is in the progress of replicating these efforts to other regencies and cities. The program’s success stories, such as those led by Zaenab, have become references of best practices to other sub-national governments to have the same commitment in strengthening women home-based workers in their area.

In MSC CPD Indonesia’s discussion with the Economic Assistant Deputy of MoWECP, Eni Widiyanti, she mentioned that MoWECP is committed to improving the conditions of women home-based workers. This commitment is also strengthened by connecting with like-minded organizations like MSC CPD Indonesia.

MSC CPD Indonesia also works on economic and financial inclusion, supporting MoWECP to strengthen women’s economic empowerment through economic inclusion and digital financial inclusion. MSC applies a gender-centrality framework to ensure its work on women’s economic and financial empowerment is inclusive and gender-responsive.

Other friends, allies, and comrades are the coalitions of civil society organizations, such as the Indonesian Homeworkers Network, the Indonesian Social Observer Foundation, and Homenet Indonesia. They have voiced and influenced the national and sub-national legislation on protecting home-based workers in Indonesia. The Ministerial Regulation on the Protection of Home-based Workers is not yet legislated. Yet at the sub-national level, local leaders have developed local regulations and policies that champion the narrative for an equal and inclusive working system for home-based workers. To name a few, local CSOs like TURC, Yasanti, and BITRA have been making progress on this advocacy in Java and Sumatra provinces.

CSOs play a significant role in connecting and networking on the issue with other strategic actors and organizations, which are potential allies in this campaign. Some conversations have also included local employment agencies, women’s empowerment agencies, and local development agencies.

MSC CPD Indonesia is also a friend, an ally, and a comrade to women home-based workers. MSC CPD Indonesia is currently developing a partnership with MoWECP to strengthen women’s economic empowerment through economic and digital financial inclusion.

Homework on home-based workers

The Rembang Regency experience led by Zaenab revealed the ecosystem of work for women home-based workers, which remains challenging. Yet these challenges can gradually be overcome with coordination, collaboration, and most of all, commitment to the recognition and protection of home-based workers. Zaenab’s experience also indicates that capacity building on gender equality and social inclusion on HBW should not be limited to the HBW. Instead, it should expand to all relevant stakeholders and key figures in the ecosystem. These stakeholders include men in the family, local and national government officials, private companies, service providers, and public institutions. Almost all have a weak understanding of the issues that women HBWs face. Strengthened coordination and collaboration can support the recognition of HBWs as workers and speed up processes to advocate policies and regulations on their protection.

Recognizing the profiles and gaps of women HBW can be enhanced by improving national and sub-national gender equality and social inclusion disaggregated data on HBWs. Such recognition will ensure they are not invisible in data. It will also ensure informed and comprehensive decision-making based on the reality and needs of (women) HBWs can fill the void on policies and development toward a decent, recognizable, and sustainable working condition for them.

Supporting the ongoing work of local CSOs and advocacy for the empowerment and protection of home-based workers is also vital. These CSOs can be partners and tandems of decision-makers and providers to assist in mainstreaming a comprehensive design and implementation of empowerment programs and policy development for and on home-based workers.

And last but not least is the inclusion of those not included in prior conversations and decision-making processes. Making room for HBWs, facilitators, companies, and service providers in the campaign and awareness dialogue and program designs on HBWs would ensure balance, meet the needs, and reinforce equity to improve their lives.

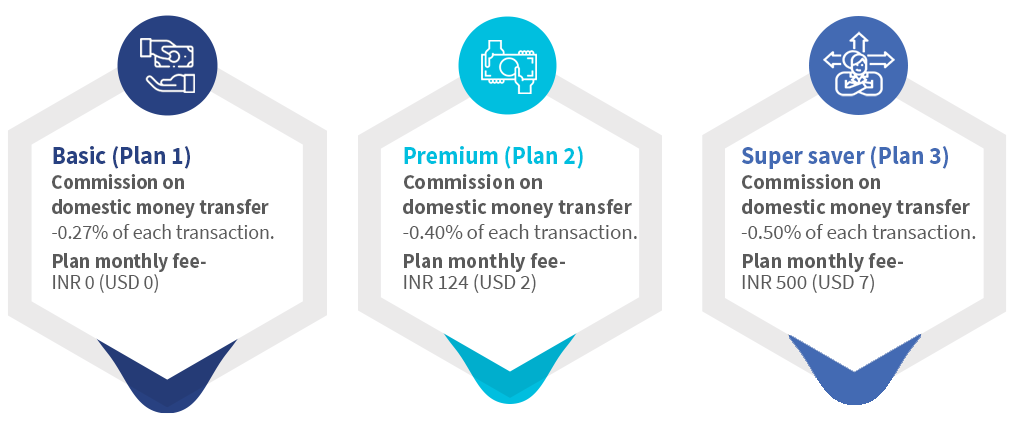

Figure 1: Old subscription plans offered by Eko to its agents (exclusive of Goods and Services Tax (GST))

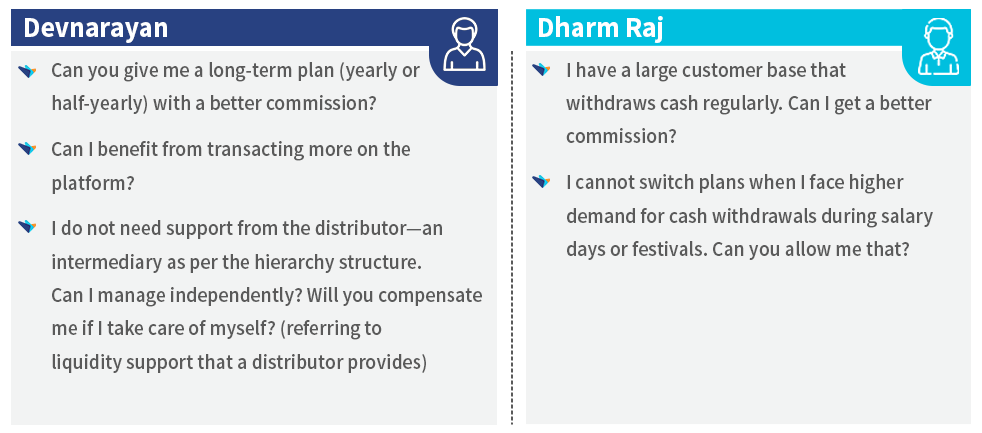

Figure 1: Old subscription plans offered by Eko to its agents (exclusive of Goods and Services Tax (GST)) However, agents and their needs are different in India. Devnarayan Chaudhary, a Business Correspondent (BC) with Eko, operates from Vishwakarma Industrial Area near Jaipur, Rajasthan. He has been associated with Eko for more than six years now. He provides multiple services like

However, agents and their needs are different in India. Devnarayan Chaudhary, a Business Correspondent (BC) with Eko, operates from Vishwakarma Industrial Area near Jaipur, Rajasthan. He has been associated with Eko for more than six years now. He provides multiple services like  In contrast, Dharm Raj, another agent with Eko for three years. He operates from Samastipur, Bihar, and faces a unique set of challenges with Eko’s plans. He mainly serves beneficiaries of various government schemes. They come to his outlet to withdraw cash through AePS.

In contrast, Dharm Raj, another agent with Eko for three years. He operates from Samastipur, Bihar, and faces a unique set of challenges with Eko’s plans. He mainly serves beneficiaries of various government schemes. They come to his outlet to withdraw cash through AePS.  Agents have a choice. Faced with low revenues, agents often reduce or eliminate transactions on a platform and move to competitors’ platforms that offer higher commissions and easy options to switch. Such departures can reduce the usage of the platform and impact Eko’s business model, which is built around agent-assisted use. In India, the DMT and AePS market has become highly contested of late. Many

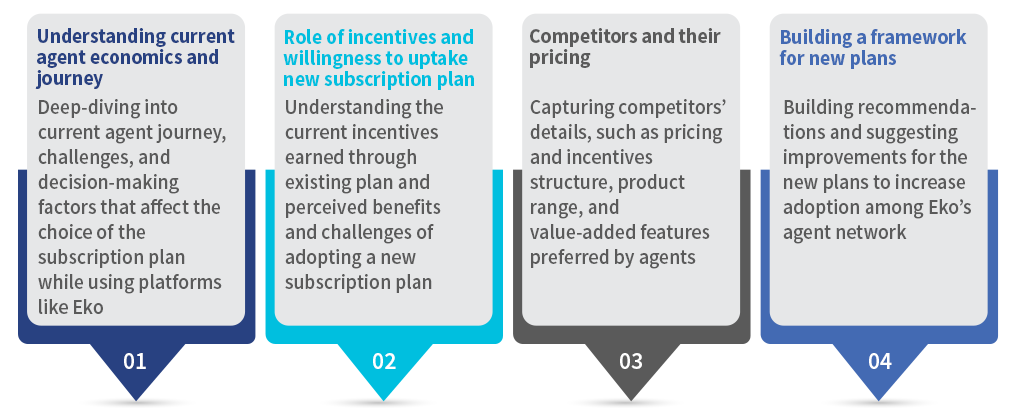

Agents have a choice. Faced with low revenues, agents often reduce or eliminate transactions on a platform and move to competitors’ platforms that offer higher commissions and easy options to switch. Such departures can reduce the usage of the platform and impact Eko’s business model, which is built around agent-assisted use. In India, the DMT and AePS market has become highly contested of late. Many  Figure 3: Focus of the assessment conducted by MSC

Figure 3: Focus of the assessment conducted by MSC Figure 4: The GBB approach suggested by MSC, Source: Harvard Business Review

Figure 4: The GBB approach suggested by MSC, Source: Harvard Business Review