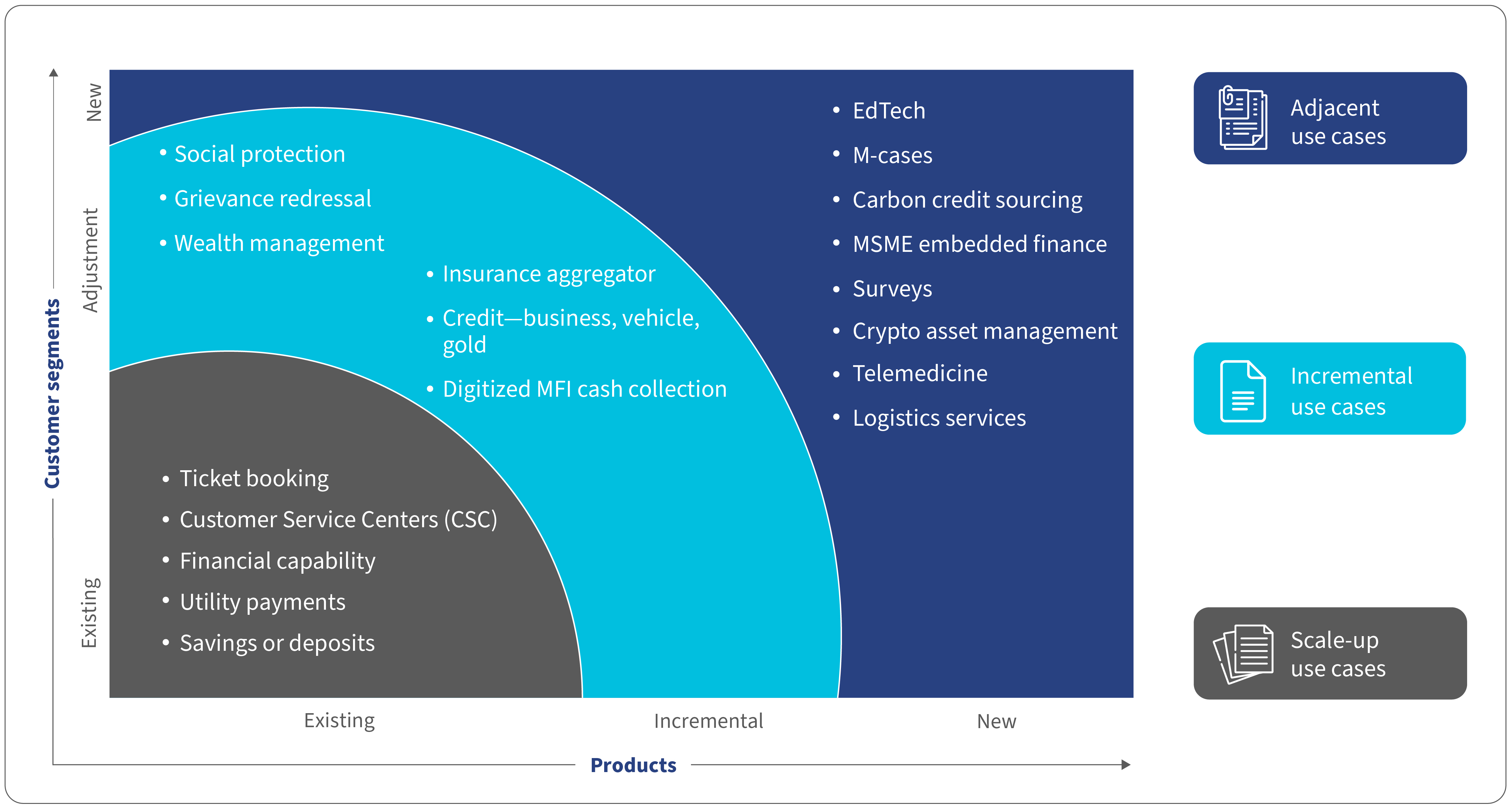

The first blog of this series discussed the importance of diversifying BC agents’ service offerings to include non-CICO products for enhanced economic viability. We also highlighted the need for training to support this shift. In the second blog, we identified potential non-CICO products through a structured framework. This blog will explore ways to train agents effectively to sell these new products.

How are agents trained when a new product is launched?

Public sector banks generally train BC agents based on the Indian Institute of Banking and Finance (IIBF) curriculum, which focuses more on regulatory compliance than practical product knowledge. This results in inadequate training on new products, shifting the responsibility to the field staff of Business Correspondent Network Managers (BCNMs). These staff members, who handle onboarding and training, often lack the resources or skills for effective knowledge transfer, leading to misinformation, often developing a ‘chinese whispers effect’ by passing on incorrect information or faulty training to agents. While some private sector and payment banks manage their own BC agent networks, their training also tends to focus mainly on operational aspects.

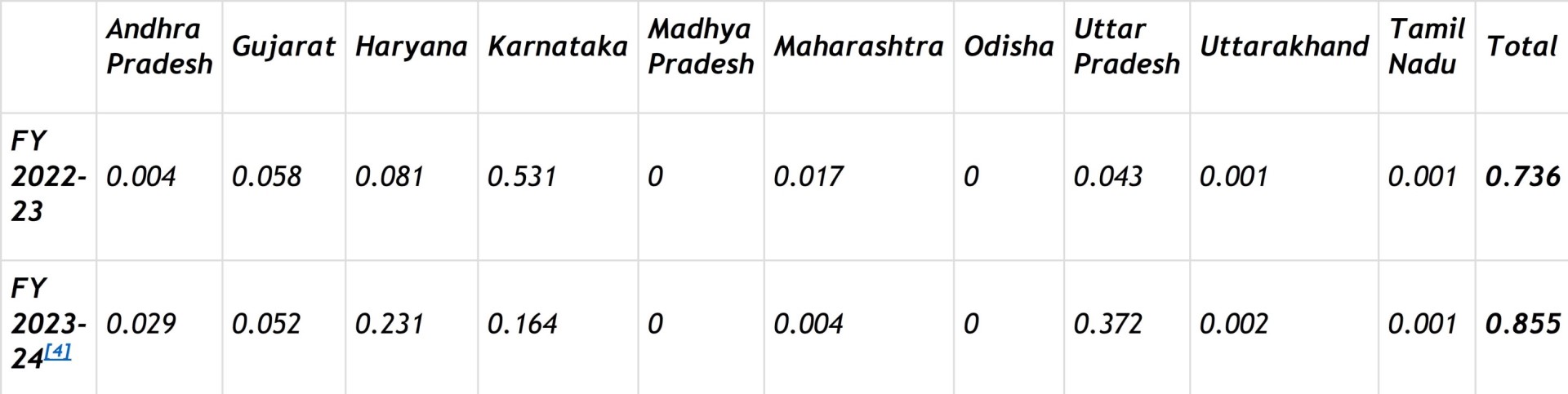

MSC’s analysis further reveals that almost all the providers we have worked with share a similar approach to introduce new products, train agents, and market these new products. Typically, most providers follow this method:

Several providers provide digital training by developing and posting instructional videos on their apps to inform agents about various products they can sell. However, a significant area for improvement that affects agents’ active use of these videos is their narrow focus on basic operational tasks. Agents are often confused about which buttons they must press or options they must select to open an account for a customer. But in addition to this, these videos fail to address the need to upskill agents to match the right product with the right customer and deliver accurate product pitches.

How can these issues be addressed?

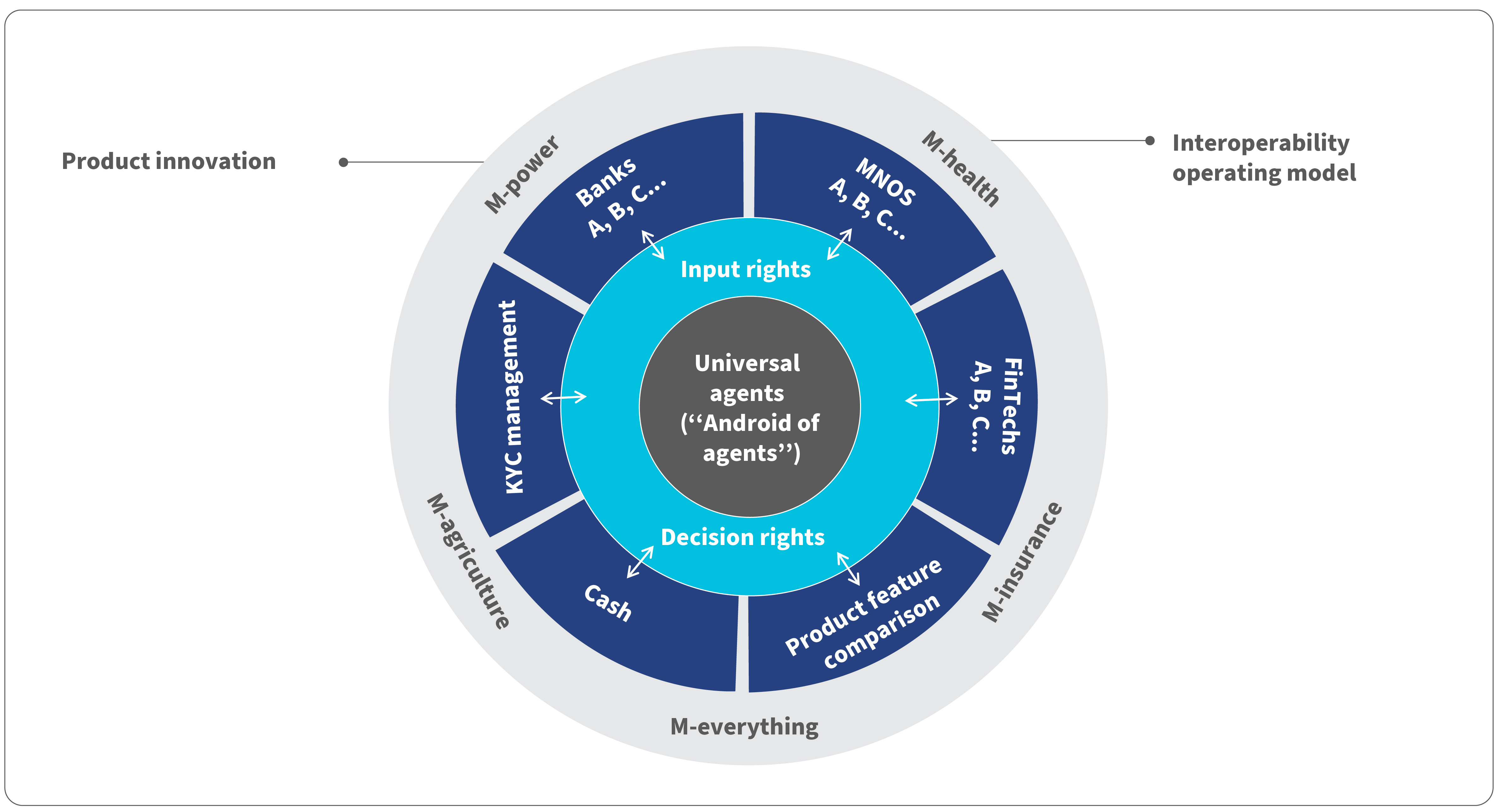

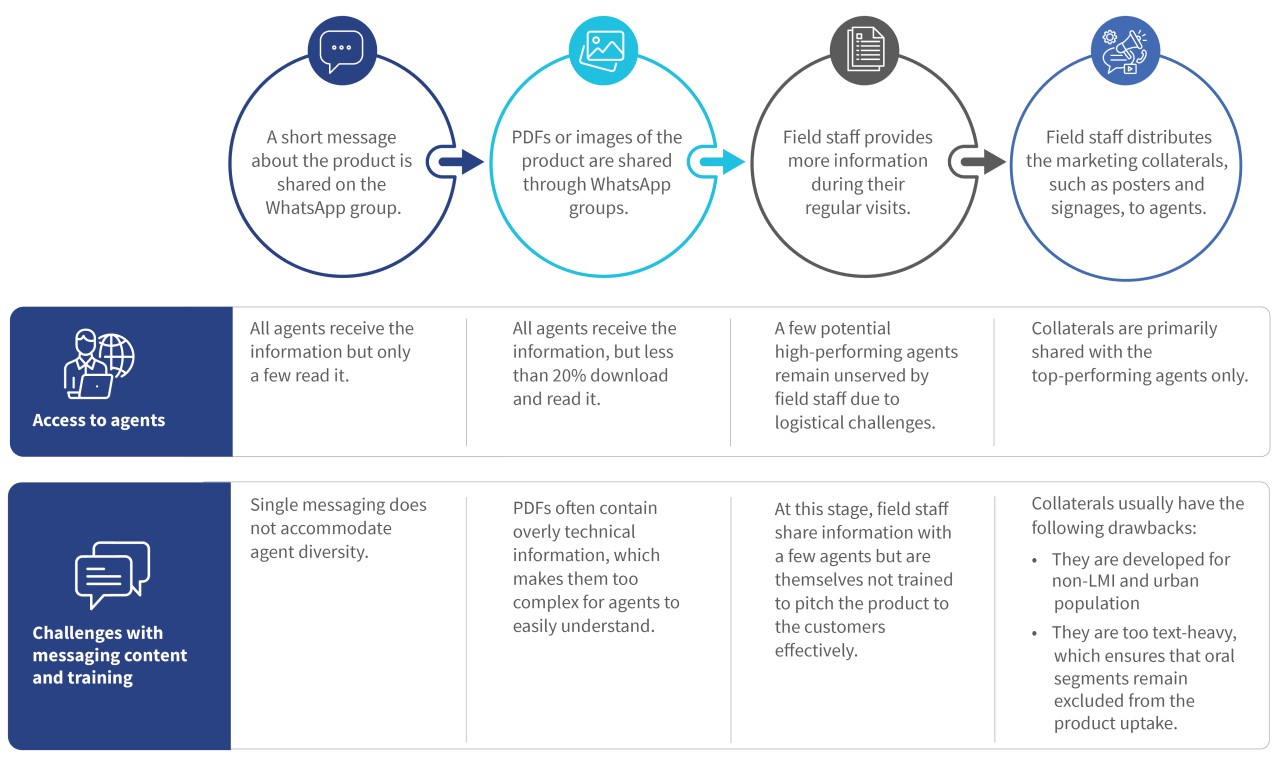

We propose the development of a “communication toolbox” to bridge this gap and ensure that the non-CICO products have a higher uptake among agents and, ultimately, among customers. A communication toolbox is a collection of marketing materials, training guides, and communication templates designed to standardize and streamline information sharing. This will ensure consistency and effectiveness. We believe a communication toolbox is essential for BC agents, specifically for non-CICO use cases, due to its flexibility and the range of resources. Non-CICO use cases include insurance, e-commerce, and logistics, among others.

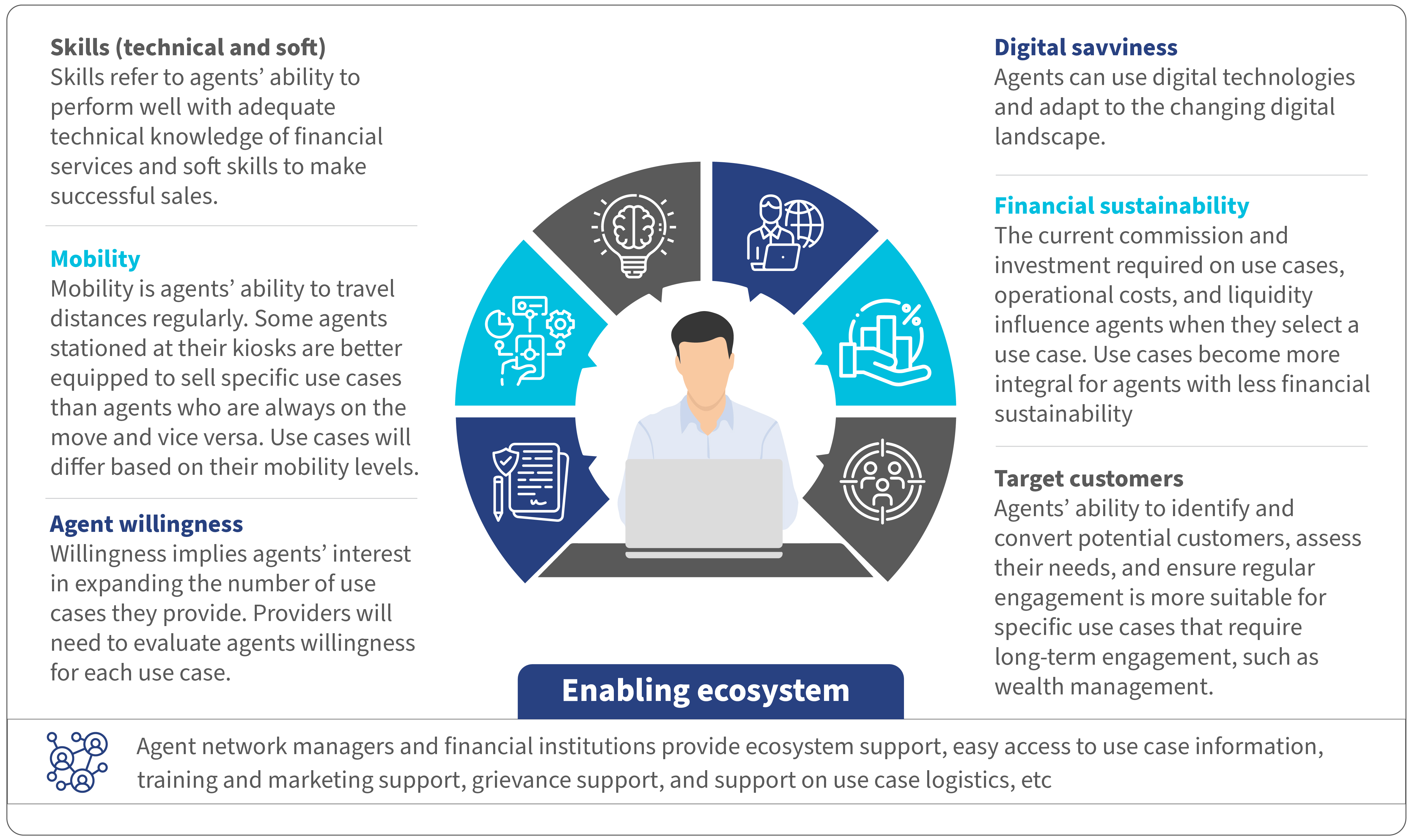

MSC has developed several communication toolboxes in the past using a design thinking approach. These are designed with in-depth behavioral research to understand the agents, their awareness levels, their preferences, their motivations, their skills, their contexts, and the challenges they face. Agent personas can be developed through this research. It can help identify key challenges and bottlenecks. These insights can be used to create the content and determine the nudges required for each agent type or persona.

A communication toolbox can potentially have the following features:

Tailored training for diverse agent personas: Insights into agent personas and agent segmentation

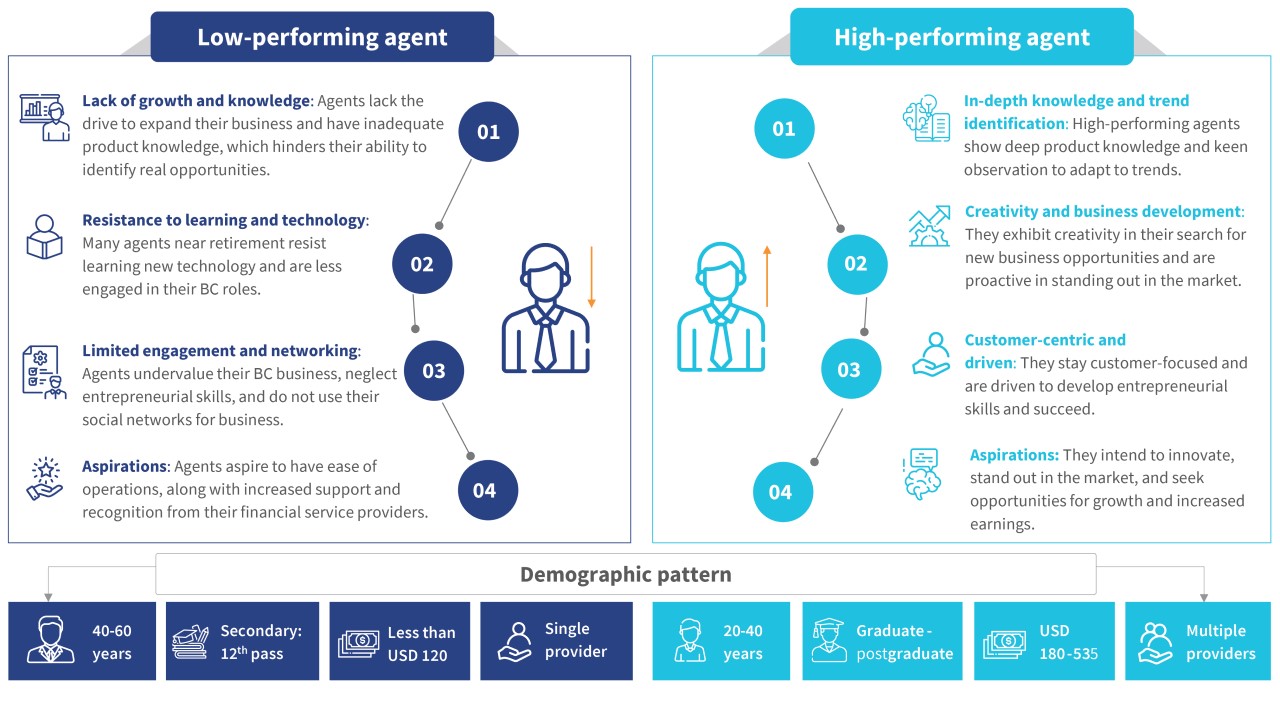

Not every BC agent is alike. Thus, stakeholders must identify different agent personas to understand their needs, experiences, behaviors, and goals. We have identified two types of BC agents based on their performance, skills, and willingness to work as BC agents to understand how they can use the communication toolbox effectively:

These personas have been developed based on our many studies with agents over the past two years. A high-performing agent is generally younger, agile, digitally savvy, and understands the customer. In contrast, a low-performing agent is often a middle-aged or older person with limited education who is uncomfortable with technology and does not have a strong customer base.

It is clear that a single line of communication will not be effective for these two agent personas due to their inherent differences in motivation and business acumen. While a high-performing agent may quickly grasp product details and target the right customers, a low-performing agent may struggle to understand the product’s technical aspects and identify suitable customers. Thus, they may struggle to pitch the product effectively.

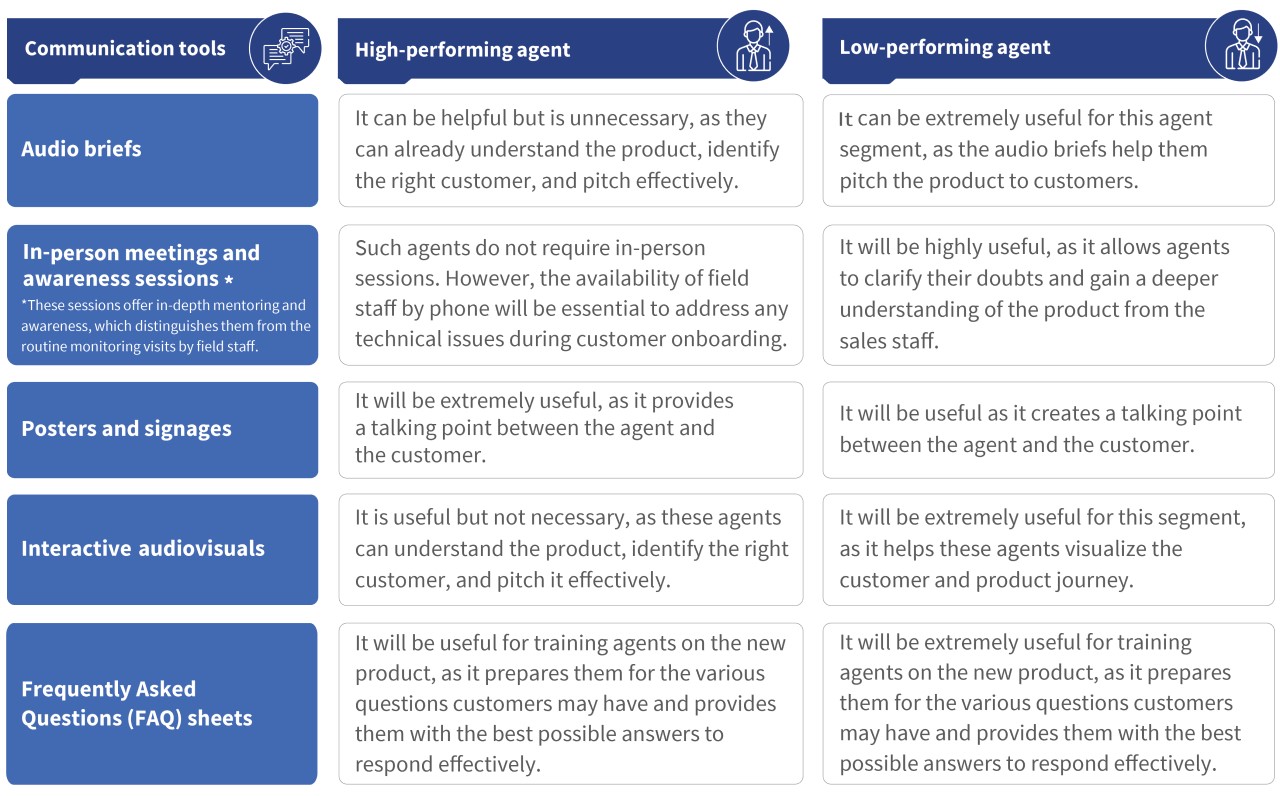

Therefore, we believe that a communication toolbox can be easily deployed for both types of agents with the agent segmentation in mind, as can be seen below:

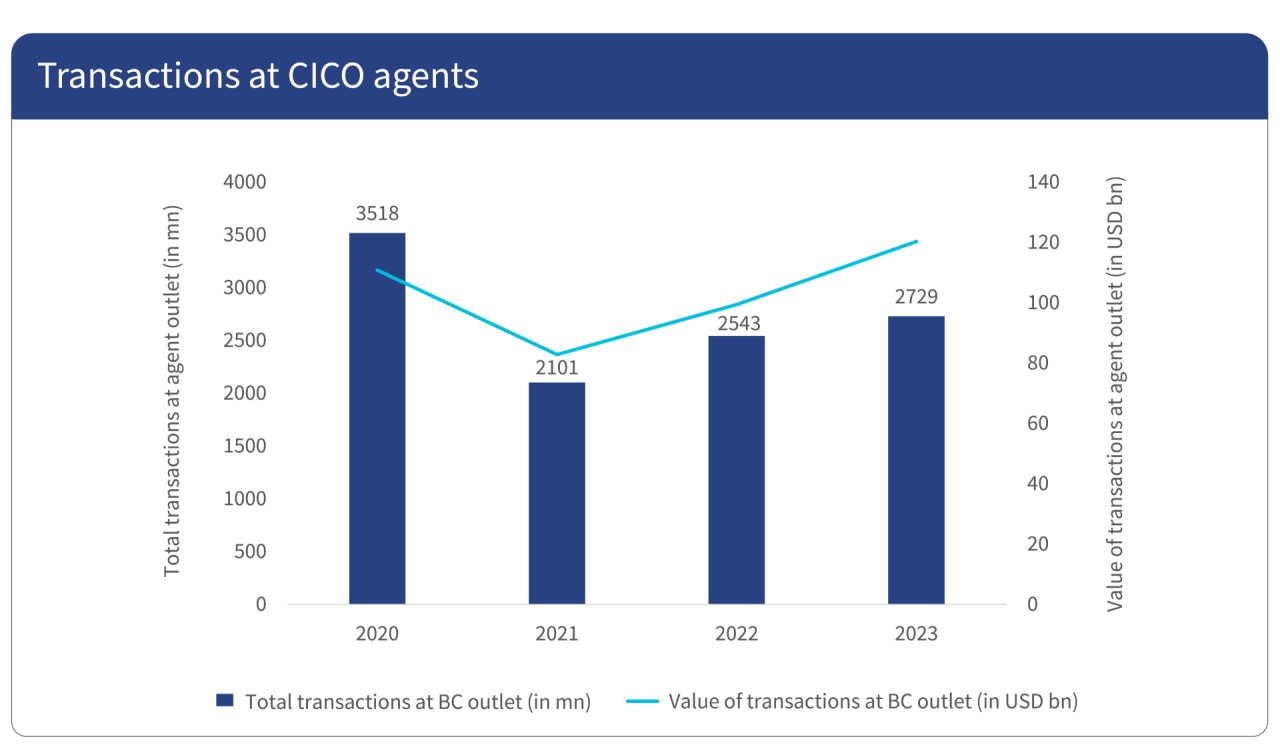

As the agent network in India matures with 2 million agents, training remains a critical yet underdeveloped area. The development of need-centric communication toolboxes is essential to improve communication and reduce information asymmetry. MSC’s previous work (1 and 2) on communication toolboxes highlights that agents become more engaged and effective in their roles when they are equipped with the right tools and training and also increase their income by 36%.

A well-designed communication toolbox can be tailored to suit the unique characteristics of different agent outlets and customer segments. It can enhance agents’ knowledge of products and their ability to pitch them to the right customers. For instance:

- Outlet size and layout: In small agent outlets cluttered with posters and other materials, signages can be developed for desks instead of walls. This will ensure the message is clear and unobstructed.

- Targeted customer segments: The images and captions on posters and signages can be customized to the target demographic.

- Use of audio tools: If the agent outlet has a speaker system, audio briefs can be tailored to directly address the target customer group’s specific needs, which will make the communication more effective and engaging.

The toolbox is a customizable template that enables agents to adapt communication strategies as per their customized contexts. This approach enhances agents’ income potential, equips them to market and sell non-CICO products more effectively, and improves providers’ overall economics.

In conclusion, the adoption of agent-segmented communication plans should be a key focus in industry players’ marketing strategies. The industry can ensure that all agents can effectively contribute to their businesses’ growth and sustainability regardless of their background or skill level through the development of communication tools that are both need-centric and customizable.