Basant Raj, 38, from Khodala village in Maharashtra, works as a daily wage worker in the nearby city and is the sole breadwinner for his family of five. Basant opened his bank account four years ago but prefers to save in cash at home. He considers formal banking channels a hassle since the nearest bank branch is far off, which requires him to travel a long distance, miss a day’s wage, and incur additional expenses to commute. Basant is among 35% of the account holders whose bank account lies dormant due to reasons, such as the large distances from the financial institution and lack of trust and need.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) constituted a committee in 2014 to bridge the burgeoning financial inclusion gap in the country and design a plan to improve access to banking services for customers like Basant. The committee floated the idea of creating a new category of financial institutions called payments banks (PBs). RBI envisaged PBs as a path to building a financially inclusive and digitally empowered country. India Post Payments Bank (IPPB) was among the 11 entities to which the RBI gave in-principle approval to set up a PB. While there were many challenges with, and questions about, the model, it was broadly seen as an important and norm-challenging approach to achieving full financial inclusion.

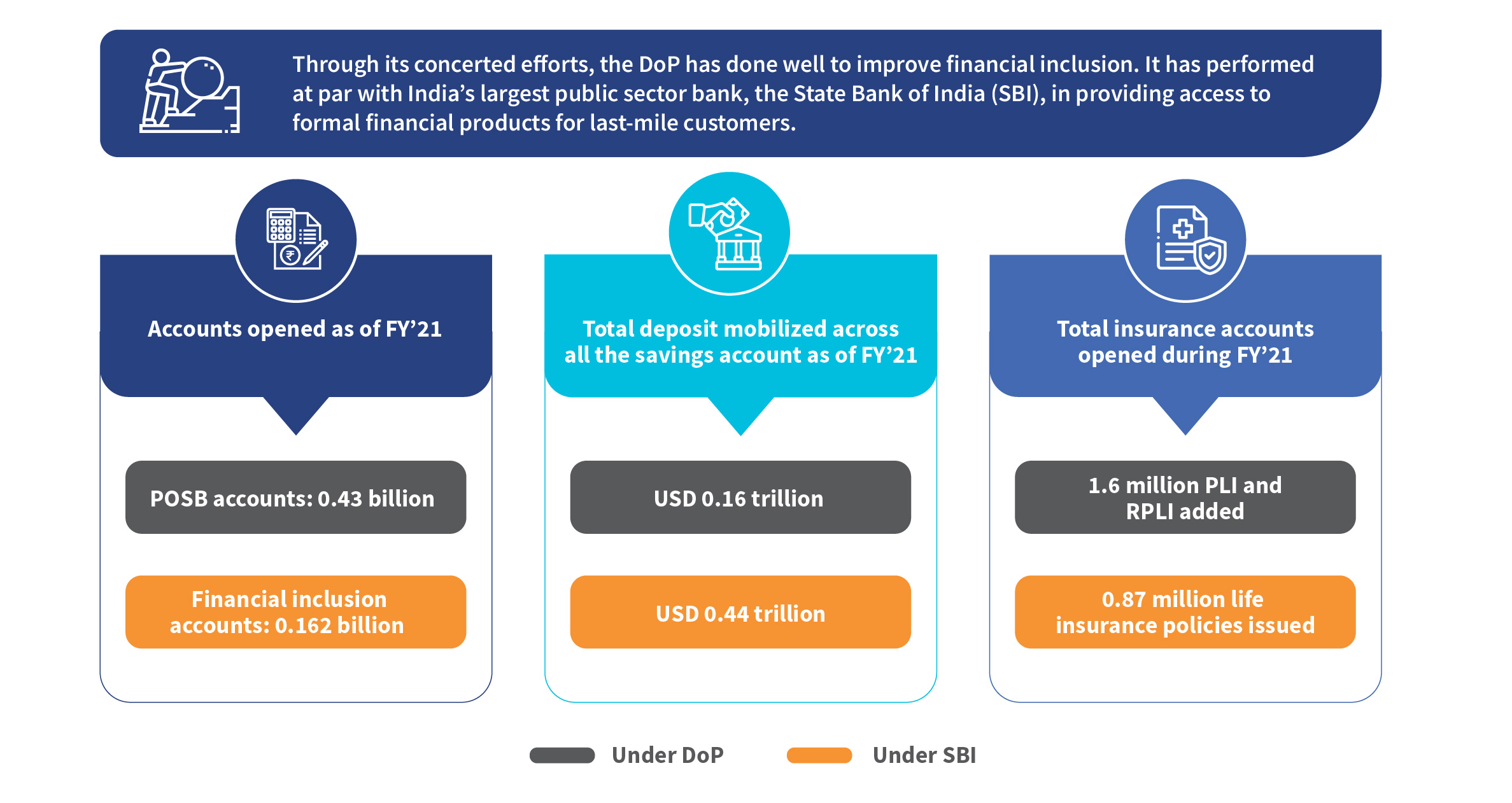

IPPB was institutionalized on 1st September 2018, as a 100% subsidiary of the Department of Posts (DoP).The DoP offers business correspondent services to IPPB through its vast network of trusted Grameen Dak Sevaks (GDS)—a colloquial term used for postal workers in India. The DoP enjoys high customer trust because of its formidable history, countrywide presence with a focus on rural India, and the Indian government’s backing. The Post Office Savings Account (POSA) offered by the DoP has been instrumental in inducing savings behavior in rural India. The insurance products offered by the DoP, such as Postal Life Insurance (PLI) and Rural Postal Life Insurance (RPLI), play a crucial role to improve the dwindling insurance penetration in rural India.

Why did IPPB and DoP collaborate?

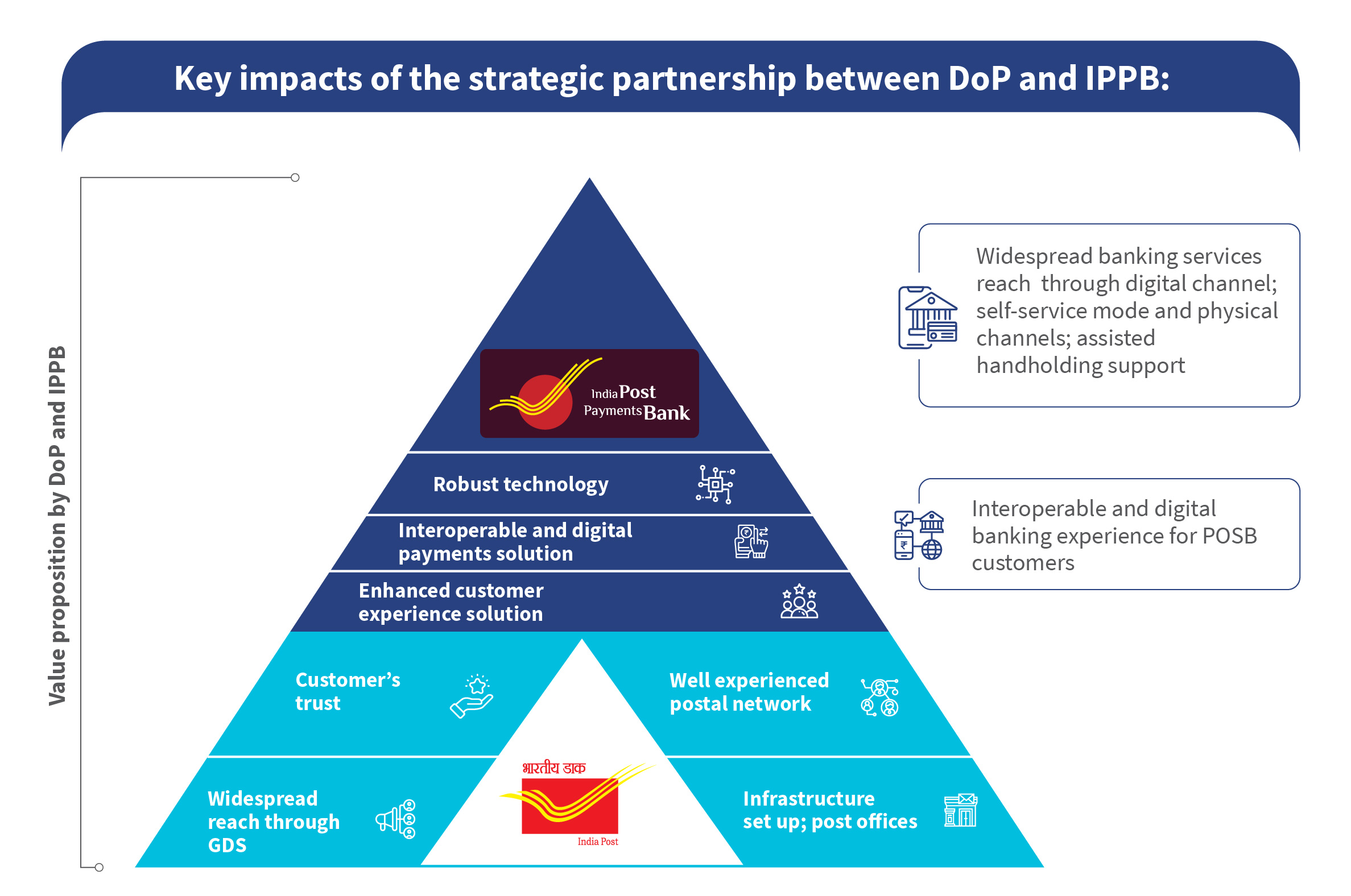

The collaboration between IPPB and the DoP created a win-win situation for both organizations through their shared vision of improving financial inclusion in India. Below is a glimpse of how this partnership has built a thriving ecosystem for each other.

Distribution and trust: The DoP was established in 1854 when letters delivered by the GDS were the only source of information that brought people closer to their loved ones. The deep-rooted trust in the postal network forms a crucial pillar of IPPB’s vast distribution network. IPPB uses DoP’s giant network of 189,000 GDS to deliver financial products and services at the convenience of the customers’ doorstep. Further, the trusted network of GDS offers handholding support to customers to bring low- and moderate-income (LMI) people into the fold of digital payments. Around 90% of IPPB’s 43.1 million customers live in rural areas.

The trust in the postal network has enabled IPPB to grow extensively. During FY 21 alone, IPPB’s customer base and their deposits grew by 83% and an impressive 169%, respectively—all at minimal additional customer acquisition cost—by using and incentivizing the existing network of GDS. The massive growth in customer acquisition is a testament to high customers trust in the partnership, which will grow over time.

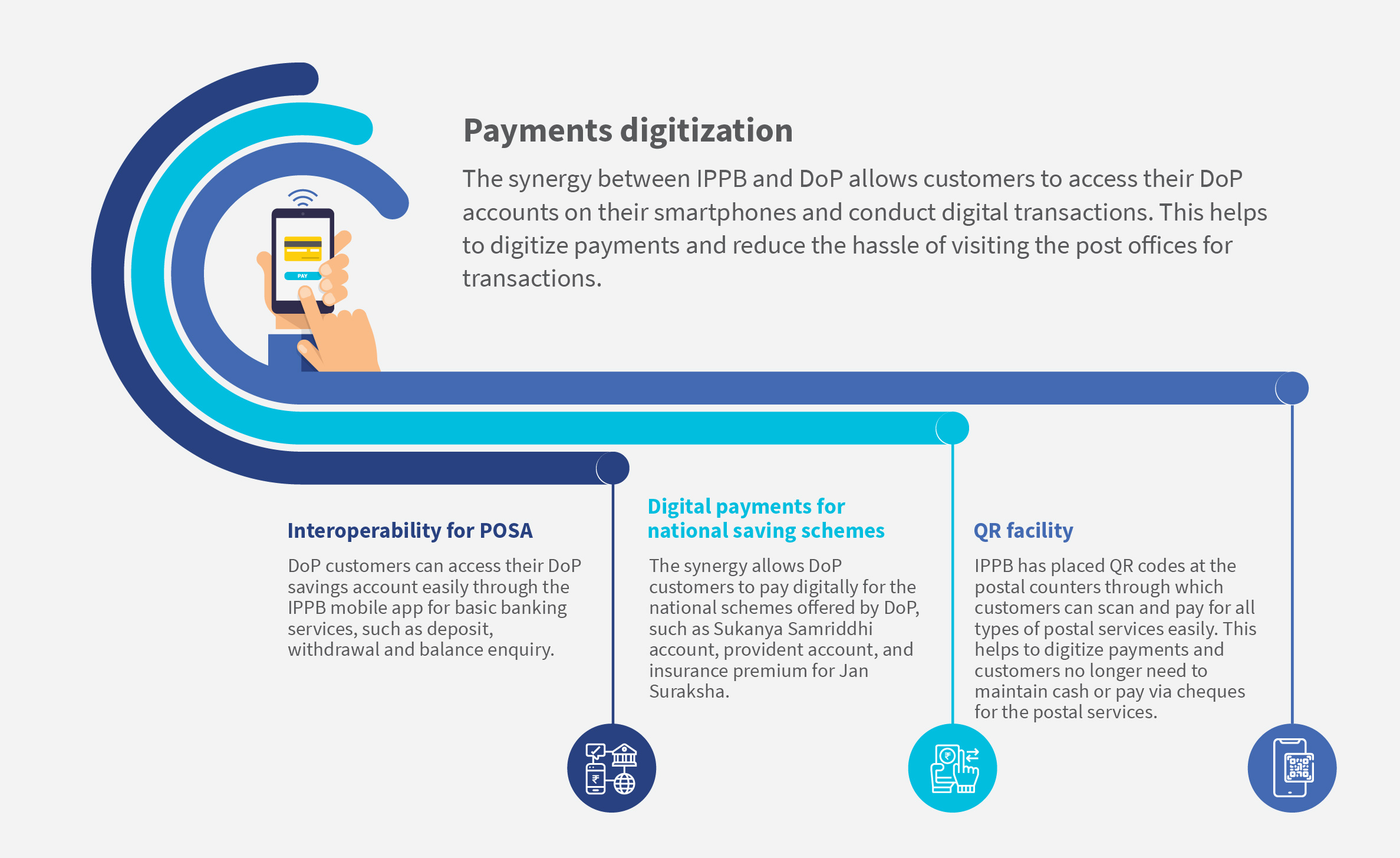

Infrastructure and technology: IPPB uses post offices spread across the country to serve walk-in customers. This helps IPPB reduce capital expenditure on constructing physical touch points or branches. So far, IPPB offers banking services through more than 136,000 post offices. Out of these, around 90% are in rural areas, which has increased India’s entire rural banking network at least 2.5 times. IPPB’s banking services allow customers to digitally transact for the various small savings schemes of the Post Office Savings Bank (POSB).

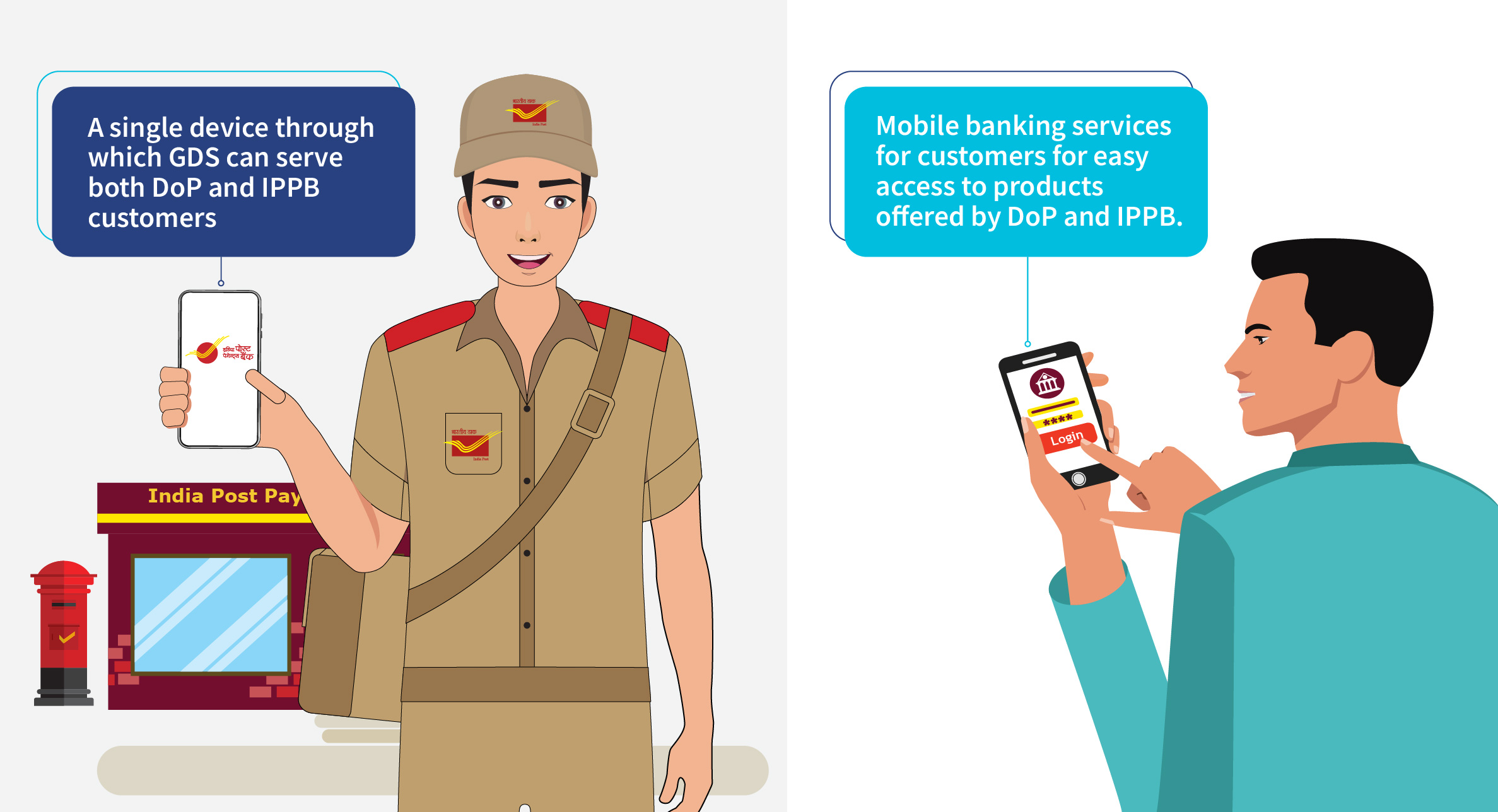

IPPB’s collaboration with the DoP helps the latter to digitize its financial offerings, encouraging active usage among customers. Its technology-first approach allows DoP customers to access their POSA through mobile banking services and use the products and services offered by DoP.

Branding and product sales uptick: IPPB enjoys widespread support from the DoP’s postal network. It helped IPPB establish itself and reach 50 million customers within just three years. Out of the total 50 million account holders, around 48% are women. Thanks to the GDS network, about 98% of women opened accounts at their doorsteps. Trust in the DoP and IPPB’s technology-first approach convinced customers of different age groups to open their bank accounts with IPPB. While the DoP already had the confidence of millennials, IPPB’s doorstep banking (DSB) and handholding services encouraged other vulnerable segments, such as women and the elderly, to start using banking services. Further, the convenience that IPPB offers through its digital-first approach has motivated Gen Z to try the postal banking product suite. Overall, 41% of the IPPB account holders are 18-30 years old.

What does this collaboration mean for the customer?

This collaboration is ubiquitously associated with improved access to digital financial products for customers. The digital transformation drive initiated by the DoP and IPPB will improve process efficiency, enhance scalability, and introduce sustainability. The collaboration has improved access to basic banking products and services through doorstep services. This allowed more usage of accounts-such as cash-in, cash-out, and payments—the lack of which remains a common problem for low-value accounts.

The widespread access to affordable and convenient financial services coupled with handholding support motivates LMI customers to use formal financial channels. This in turn has immense potential to improve customers’ financial health and safeguard them against financial shocks.

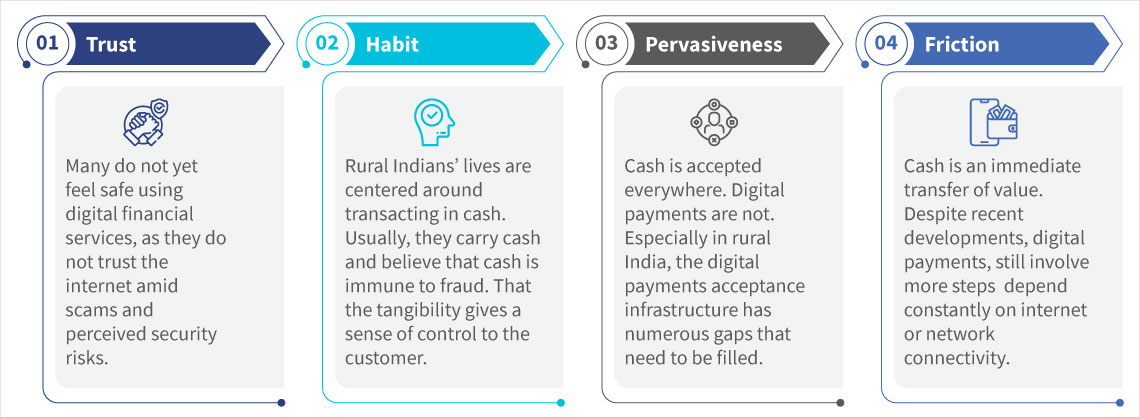

Due to limited digital and financial literacy, most rural customers feel intimidated by digital interfaces. They require strong social proof to use formal financial channels and generally exhibit status-quo bias. Despite these challenges, IPPB retains a robust, rural customer base, whom it has offered doorstep banking to help kick-start its formal financial journey. IPPB has influenced a behavioral shift among the rural segment—another feather in its cap.

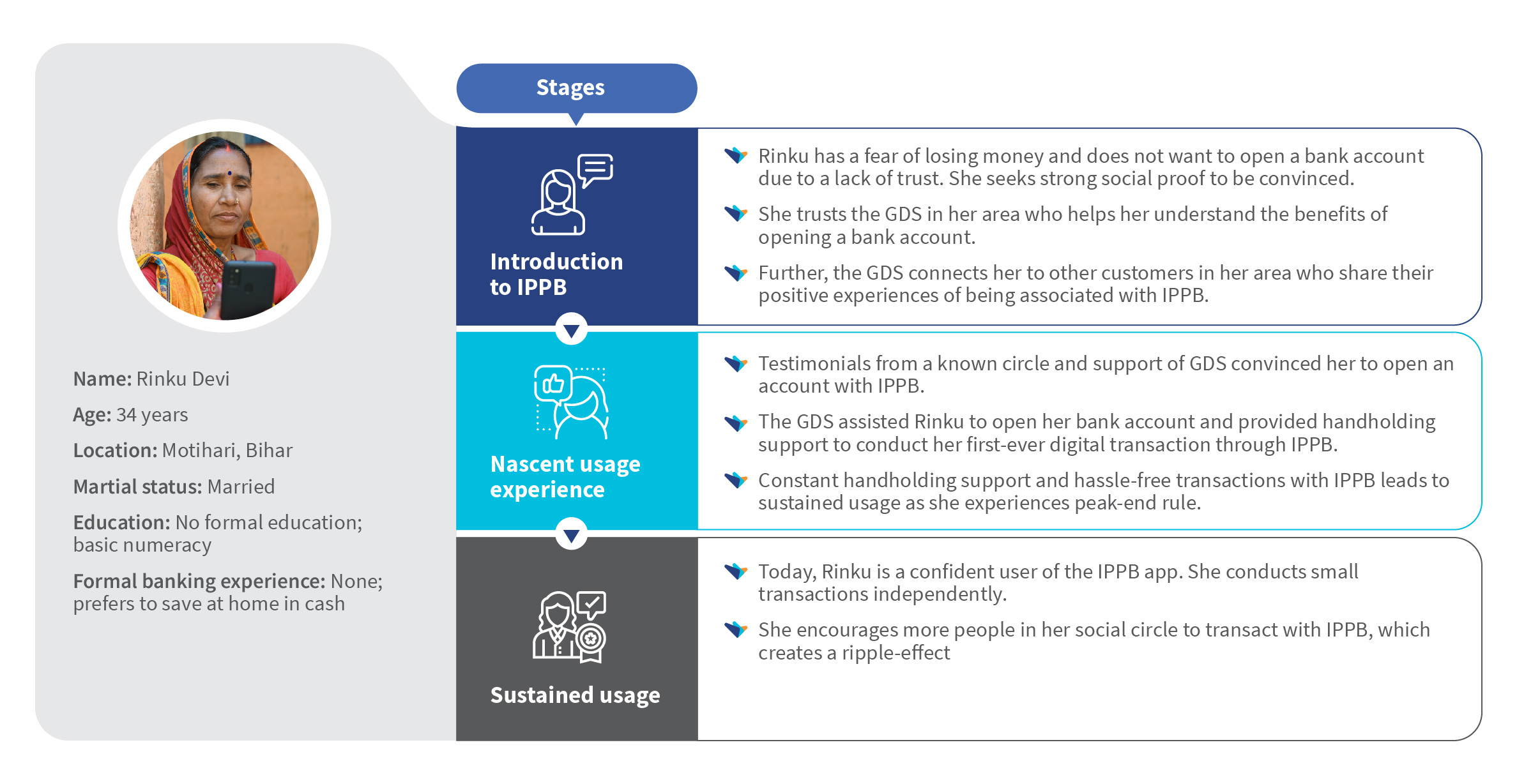

Here is how the GDS put Rinku Devi—a stay-at-home mother from the Motihari village in Bihar—onto her path to financial inclusion:

The road ahead

Despite the collaboration, IPPB and DoP must resolve any underlying challenges if the network is to function to its optimum capacity.

- Device and workload management: The shift from being postal workers to financial inclusion enablers implied increased responsibilities for the GDS. While IPPB’s training helped in this transition, a GDS needs to manage different devices to serve customers using DoP and IPPB products, which is inconvenient. Providing a single device to the GDS to manage both IPPB and DoP operations is a possible step to streamline their workflow. Unifying IPPB and DoP at the technology and performance matrix level will further help streamline the operational and functional responsibilities of the GDS. The unison has immense potential to transform the GDS into a force to reckon with, pushing financial inclusion to the next level.

- Skillset requirements: GDS is a heterogeneous group with varying levels of digital literacy. The varied skillset and tech-savviness required to manage different devices and solutions for DoP and IPPB often overwhelm them. This impacts their performance and impedes their ability to assist more customers. A combined induction and capacity-building program that intersperses DoP’s mail operations training with IPPB’s banking operations training can help gradually upskill the GDS. If mail operations and banking operations are on the same platform, the smooth user experience of using the app can reduce the cognitive load on the GDS. Furthermore, a unified performance evaluation system of the GDS would go a long way to keep them motivated. The basic tenets of the unified device include a customer-centric approach, technology-backed infrastructure, and a focus on the well-being of the postal network.

IPPB—the digital engine of inclusive growth

IPPB is on a path to revolutionizing the digital banking experience for customers through the unprecedented reach of the postal network. The innovative steps that IPPB has taken, such as DSB, distributing digital life certificates, and paperless transaction receipts, have paved the way for a digital transformation even in the country’s hinterlands. Between 2019 and 2021, IPPB processed 48 million doorstep transactions and mobilized social security payments worth USD 0.39 billion for rural customers. Extensive handholding support through the trusted GDS network paved the way for affordable and accessible financial services for millions of customers, especially women and senior citizens. These milestones signify that IPPB has immense potential to turn digital India’s dreams into reality.

Bhupen, a 23-year-old from Tripura, is a full-time owner and chef at a small eatery in New Delhi. He has earned a reputation as one of the best chefs in the area for budget Chinese takeaways. Bhupen’s job keeps him busy since the cafe is located near a popular corporate office. This leaves him with few opportunities to visit his family back in Tripura

Bhupen, a 23-year-old from Tripura, is a full-time owner and chef at a small eatery in New Delhi. He has earned a reputation as one of the best chefs in the area for budget Chinese takeaways. Bhupen’s job keeps him busy since the cafe is located near a popular corporate office. This leaves him with few opportunities to visit his family back in Tripura

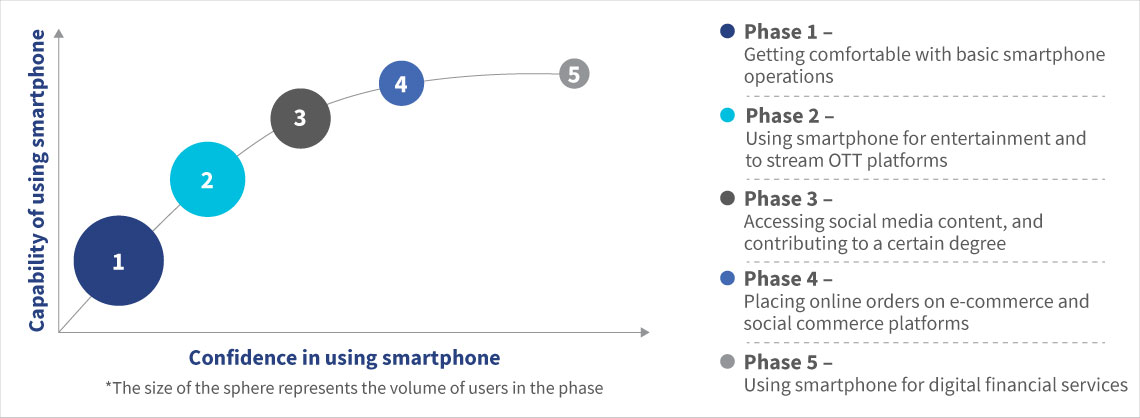

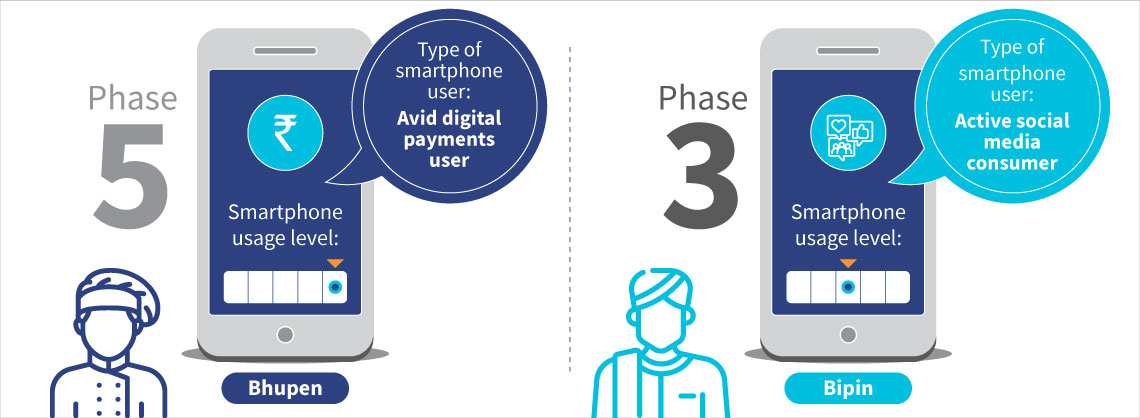

Figure 3: Level of smartphone usage by Bhupen and his father

Figure 3: Level of smartphone usage by Bhupen and his father

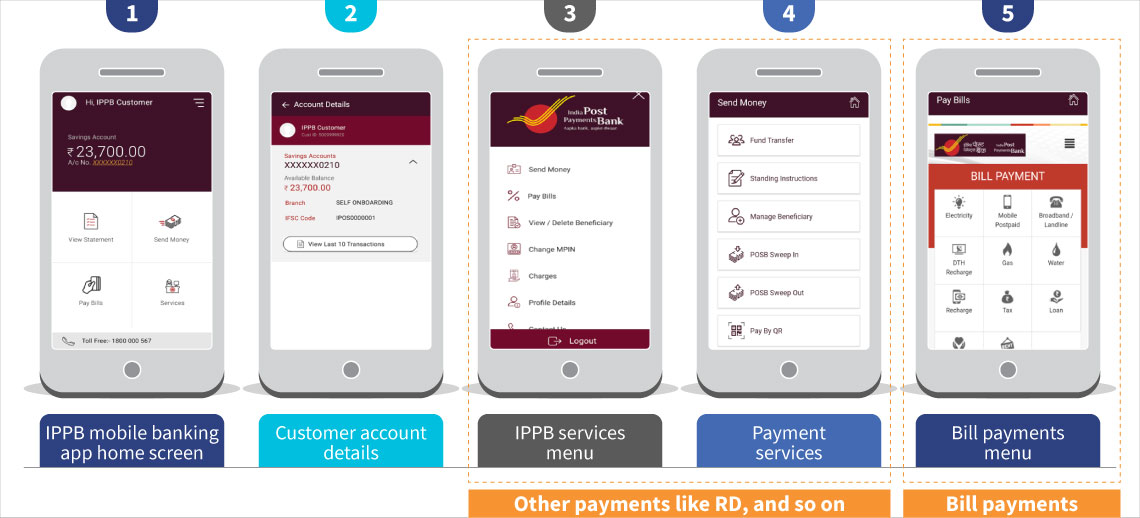

Figure 5: IPPB mobile banking application – services menu

Figure 5: IPPB mobile banking application – services menu

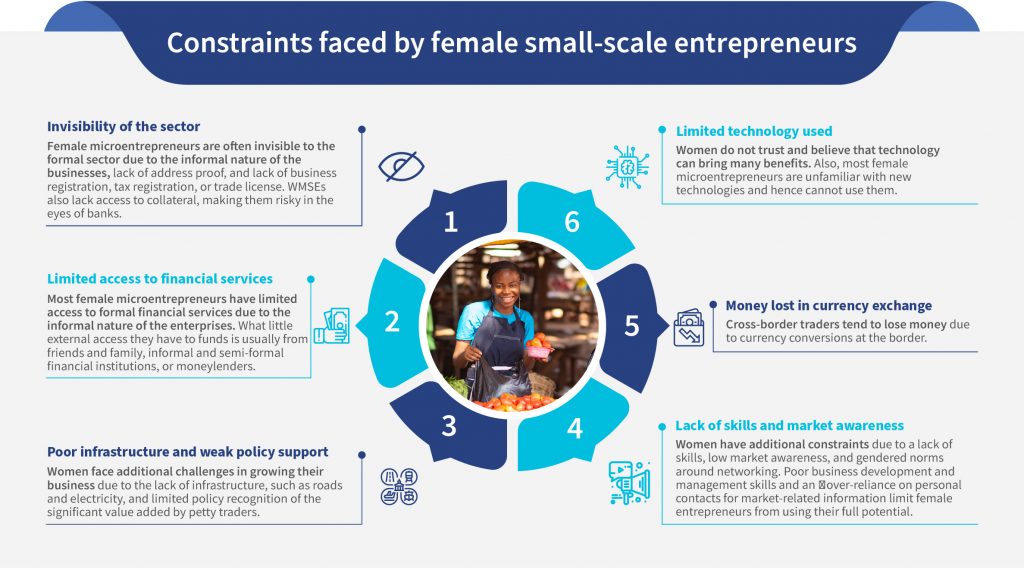

Faith wants to rear chickens and fatten pigs since she heard from her friends that these ventures offer high margins. She believes diversification will help her overcome cyclical downturns in business and increase her earnings. Faith also dreams of transitioning from operating in open-air markets to running her business in a permanent structure—for which she would need access to formal financial services—and credit—often unavailable because she lacks collateral. The digital resources available are expensive and provide small loans that fail to meet her business needs.

Faith wants to rear chickens and fatten pigs since she heard from her friends that these ventures offer high margins. She believes diversification will help her overcome cyclical downturns in business and increase her earnings. Faith also dreams of transitioning from operating in open-air markets to running her business in a permanent structure—for which she would need access to formal financial services—and credit—often unavailable because she lacks collateral. The digital resources available are expensive and provide small loans that fail to meet her business needs.