The River Ganges and its many tributaries are India’s cultural and economic lifeline. The mighty river originates in frozen glaciers in the northern Himalayas and empties into the Bay of Bengal to the east. As it descends to the ocean, its tributaries criss-cross several states, including the eastern Indian state of Bihar. The river network provides silt-rich soil and critical irrigation to the state and its neighbors. Yet climate change in recent decades has turned this blessing into a curse, increasing flooding in the Gangetic plains. Estimates indicate 45.24% of Bihar state’s area is flood-prone. North Bihar is more prone to flooding due to rainwater runoff from neighboring Nepal and fluvial flooding of the Gandak and Kosi rivers. The increasing heat and humidity intensify localized rainfall and thus risk pluvial flooding.

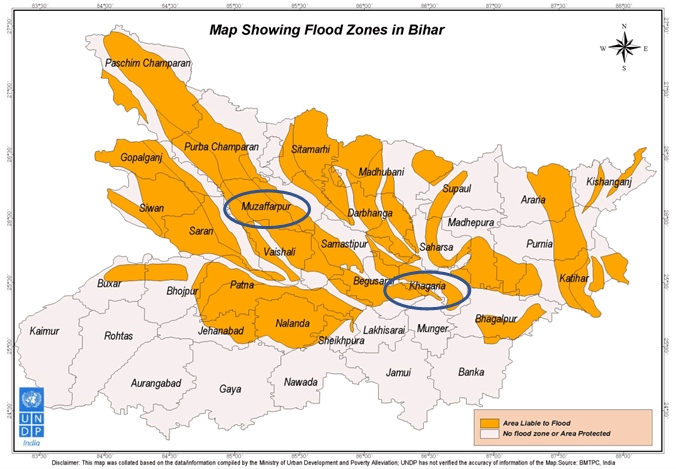

MSC conducted qualitative research to understand the needs, aspirations, perceptions, and behavior of smallholder farmers in Muzaffarpur and Khagaria—two districts most impacted by these climate change events.

In our focus groups and interviews, smallholder farmers unanimously stated that flooding is the worst weather hazard in their villages. Class-III floods caused due to congestion at the river confluence are the most damaging. Class-III floods last the entire monsoon season. They lead to waterlogging of low-lying farmlands, damage crops, and drain away the fertile topsoil when they recede.

The respondents in Muzaffarpur recalled the devastating 1987 floods and, more recently, the Class-III floods in 2020-21. In Khagaria, respondents recalled floods in 2002, 2004, 2007, and again in 2021 due to heavy rainfall in the region. The smallholder farmers also mentioned increasing humidity and the rise in cyclonic rainfall. Respondents in both districts noted heat waves in the past two years had also damaged crops.

“The dry spell is followed by heavy rains. The weather is becoming like that of Odisha and West Bengal—hot and humid.” – Sunaina Saran – Sarmaspur, Muzaffarpur, Bihar.

While flooding is the major climate hazard in our selected geographies, the impacts of slow-onset climate hazards were also evident in declining crop nutrients, increased incidences of pest attacks and pathogen infestation in crops and livestock, and declining health of the village populace. We examine these under six categories below.

Agriculture

The seasonality of flooding means that it most commonly damages Kharif crops, such as rice and maize. The erosion of topsoil strips away soil fertility and diminishes marginal yield from the application of fertilizers, risking spiraling and increasingly ineffective overuse of fertilizer. Farmers have attempted to maintain their income levels by resorting to planting short-duration, high-yielding vegetable crops and using hybrid seeds and heavy doses of chemicals. Moreover, the increasing incidence of pest infestations and pathogenic attacks as a result of the increased humidity has forced farmers to apply more pesticides.

Livestock

Farmers report increased diseases among cows like foot and mouth disease, mastitis, enteritis, hemorrhagic septicemia, and high fever. In response, they use more medicines on a prophylactic and curative basis. The excessive use of such chemicals in farming affects the nutritional quality of milk. But the higher mortality rate of cattle affects their income stream and leads to a loss of investments made in insemination, buying calves, veterinary fees, fodder, and other input costs.

Finances

Farmers are concerned about the declining marginal return from crops as they have to resort to more expensive hybrid seeds, grow perishable produce, and use more costly inputs, particularly fertilizer and pesticides. As a result, they report increased demand for credit from local moneylenders, self-help groups (SHGs), and microfinance institutions (MFIs) for consumption smoothing, and to make the necessary investments in the next agricultural cycle. Several respondents reported that their earnings declined while they exhausted existing savings.

Health

Incidences of health issues, such as fever, weakness, waterborne diseases, cough, cold, knee pain, and weak eyesight are reported to be increasingly common among villagers. Worsening physical health is seen by our respondents as the result of the decline in the nutritional quality of food from the over-application of fertilizers and pesticides. Furthermore, many reported increased emotional stress due to illness, injury, loss of physical and financial assets, and the uncertainty arising from the changeable weather patterns.

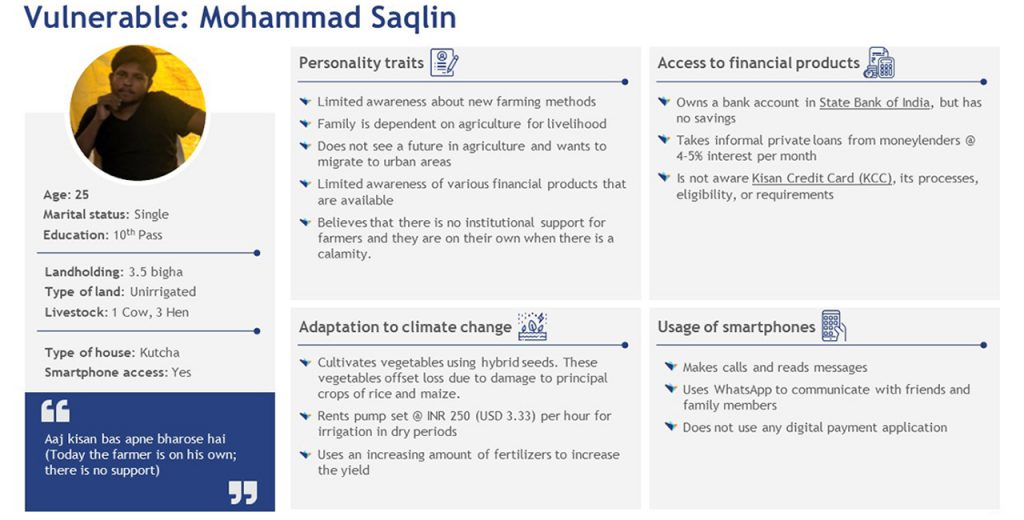

Migration

Respondents noted an increasing propensity among youth to migrate and work away from their family farms. However, we could not establish a correlation between changing weather patterns and this rising propensity to work in the non-farm sectors. Some of this migration is clearly due to reduced income from agriculture and the fragmentation of landholding due to inheritance norms. Yet much of this trend also arises from urbanization and exposure to digital media.

“The number of people engaged in agriculture has fallen over the years. Migration to cities has become common; for most families, at least one family member lives outside the village and sends money home. With current vegetable prices being as low as INR 2 per kilo, farming is no longer profitable, so having alternate family income sources is crucial.” – Focus group in Itha Rasulnagar village, Muzaffarpur, Bihar.

Infrastructure

Severe floods, such as those in 1987 and 2007, have caused significant damage to houses, especially mud houses, roads, and electricity transmission structures. However, the more frequent pluvial floods that take longer to clear make access to services a major challenge.

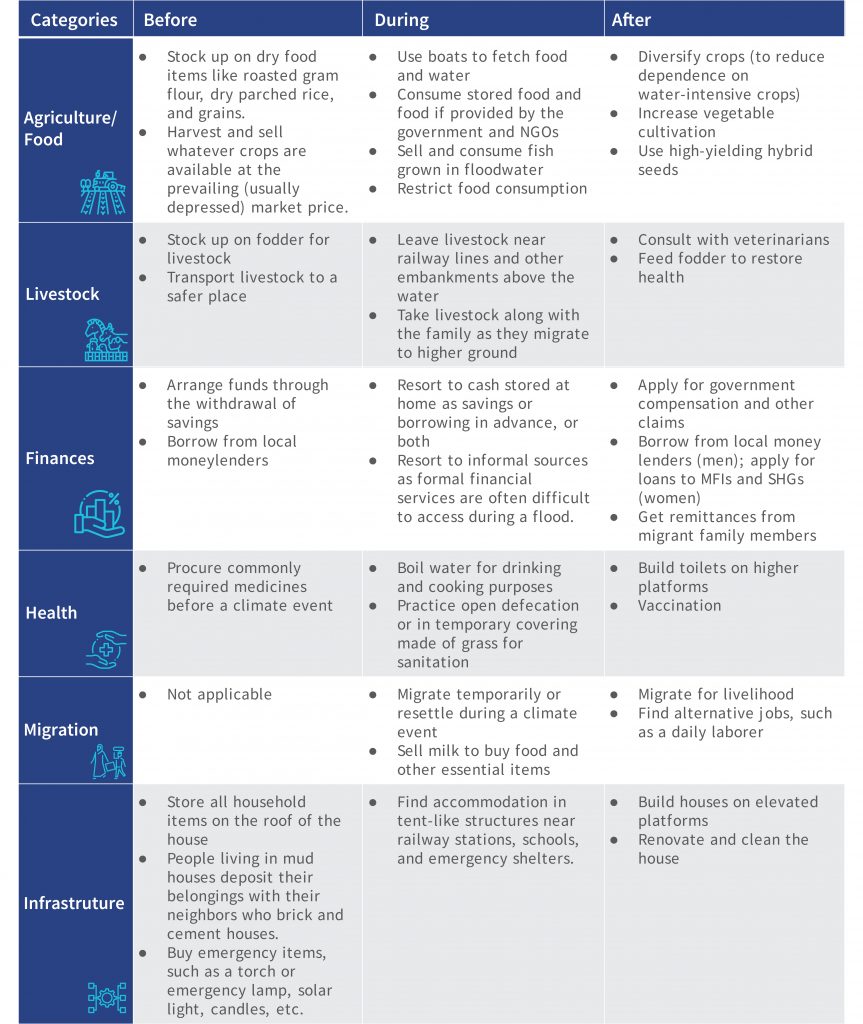

So how do smallholder farmers respond to climate events, such as floods?

We discussed adaptation strategies used by farmers before, during, and after floods. A clear pattern emerged that the table below summarizes using our six categories.

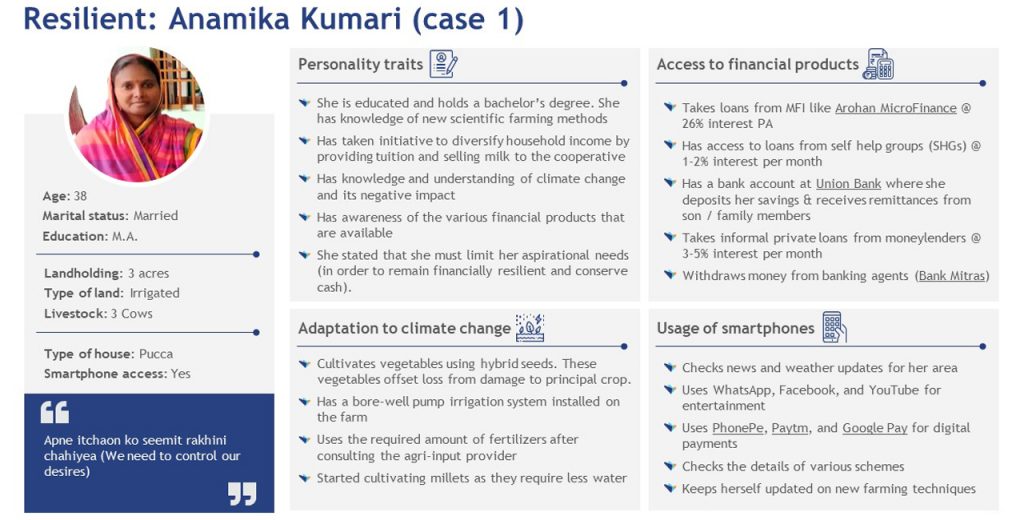

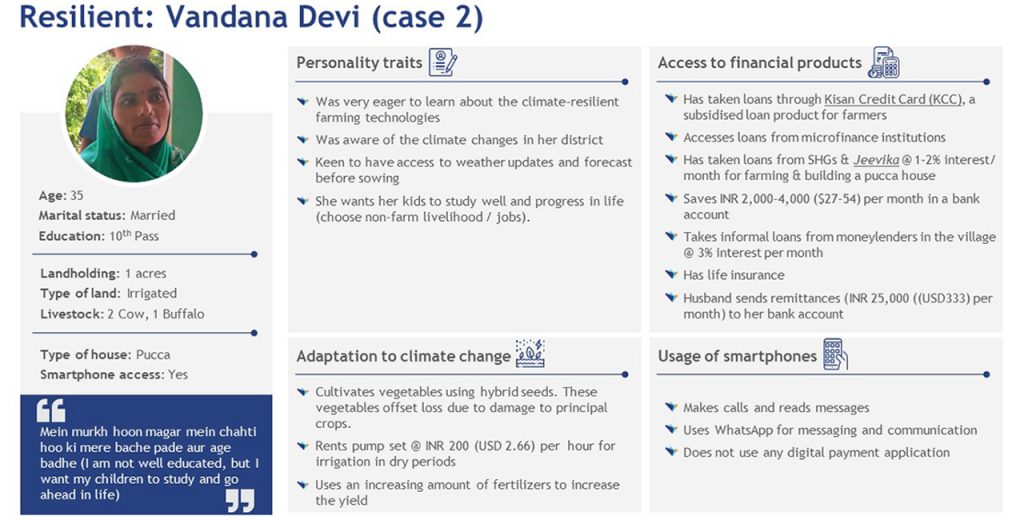

Our next blog in this series uses persona analysis to explore the traits of resilient and vulnerable smallholder farmers and examine how gender influences the experience and impact of climate events.