“Do not trust banks” and “avoiding a bank gives more privacy” were among the top most cited reasons why people choose to not have a bank account, as per the 2021 National Survey of unbanked and underbanked households by Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

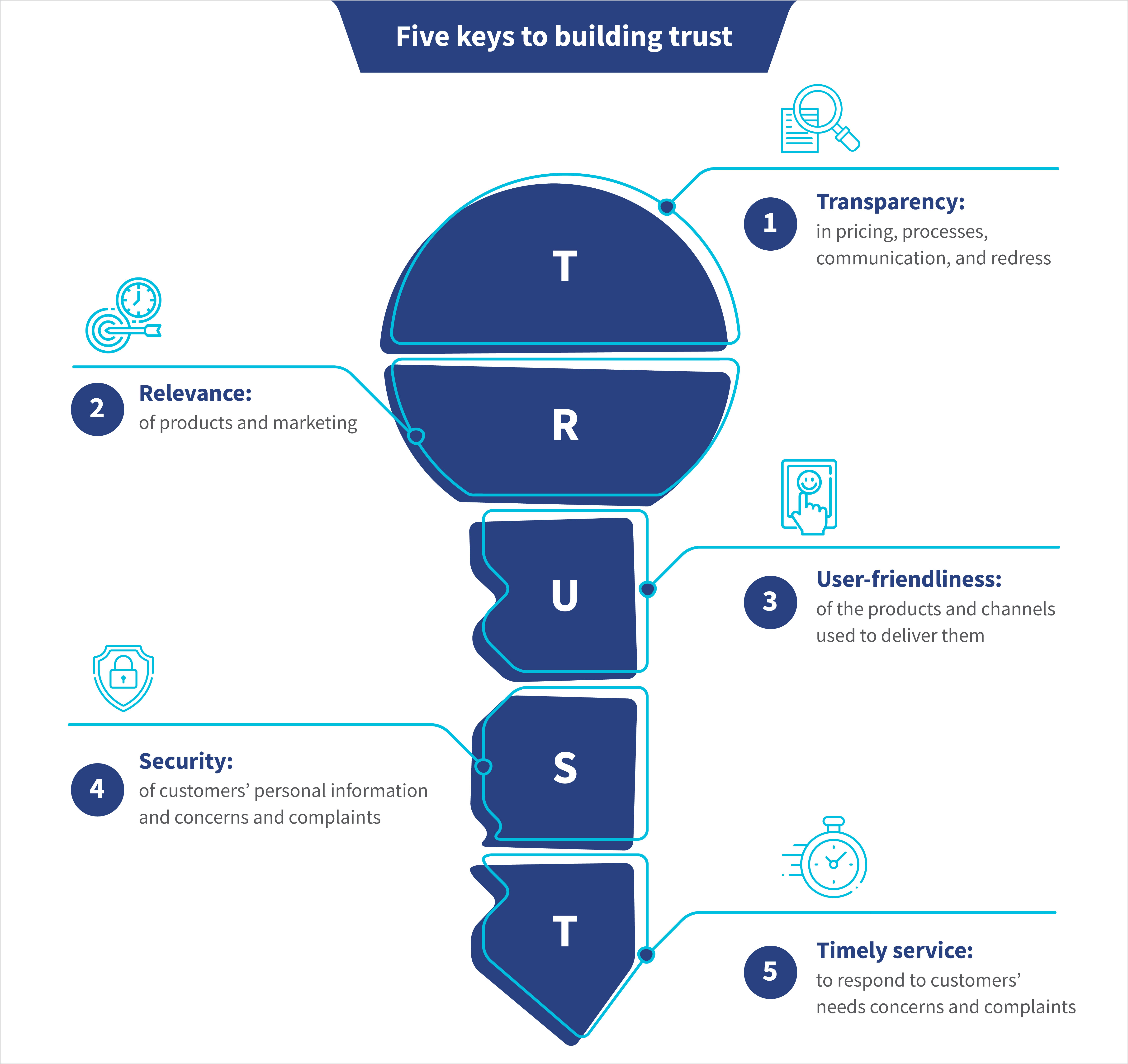

Customer trust ranks as a priority for financial service providers (FSPs). Consumer protection is pivotal to foster this trust. It is a fundamental pillar of a secure financial system. It is essential for financial entities to streamline their products and services and, in the process, foster customer trust and safeguard their interests.

MSC has taken active steps to safeguard customers by increasing awareness of emerging risks. We collaborate with various stakeholders, such as FSPs, investors, and policymakers, to ensure that their practices prioritize customer well-being. This blog explores the significance of TRUST in financial services and offers FSPs a checklist to strengthen consumer protection.

- Transparency: The first principle to build customers’ trust is to ensure transparency in the design of financial products and services. FSPs must disclose information on product features, guidelines, fees or subscription charges, terms and conditions, complaint management systems, etc. They can share this information through multiple channels, such as websites, SMS, calls, and printed disclosures, among others. Clear explanations of processes empower customers with a comprehensive grasp of the underlying rules. The provision of sufficient information to customers about FSPs’ operations can bolster their credibility. FSPs should also employ principles of behavioral science to simplify communication through tools. These include nudges, disclaimers, cool-off periods for consent, and prompts. These tools can increase understanding among customers, nudge customers to make informed choices, and provide timely information. Behavioral insights can also be used to conduct pilots and experiments to assess the effectiveness of various transparency measures. FSPs can help consumers stay informed and increase accountability, user-friendliness, and transparency in their processes.

- Relevance: Relevance refers to assessing if the products sold are suitable for the target consumer groups. Financial awareness is low in most developing geographies. Hence, it is easy to manipulate large audiences to avail of products and services that are unsuitable for them. For example, customers have fallen victim to mis-selling when they are sold insurance plans instead of loans or savings and endowment plans instead of term insurance. Customers often struggle to understand the intricacies of the product due to agents who intentionally mislead customers and push them to buy unsuitable plans. Similarly, many customers are pushed to buy policies to get bank lockers or loans. FSPs should guarantee regulatory compliance to ensure that products are sold in a clear and transparent manner only to relevant consumers and protect their interests. Agents are often incentivized based on the number of policies they sell as opposed to how well they explain the product features and processes to their clients. This brings us to the theme of designing incentive structures for insurance agents to protect consumer interests and reduce instances of fraud, misinformation, grievances, and complaints against insurance companies. FSPs should also use advanced analytics to analyze product suitability-related complaints registered by the customers. This can be a useful tool in self-evaluation for FSPs to monitor how well their products are mapped to their targeted market and needs. Advanced analytics and analysis of product suitability will also encourage FSPs to design better incentive structures and training programs for insurance agents so that they can ethically market insurance policies to potential customers.

- User-friendliness: FSPs should ensure that the products and services offered to customers are user-friendly, easy to comprehend and navigate, and accessible through multiple channels, both physical and digital, to cater to a diverse range of users. The user interface’s ease of use and navigation, which encompasses the website, mobile applications, IVRS, and chatbots, is essential. At the same time, training for agents and staff is imperative to always uphold a customer-centric approach. FSPs should use behavioral economics to create and design interfaces that encourage responsible financial behaviors.

- Security: FSPs should strengthen the security of financial products and services to protect customers’ personal information and assets. They must ensure that the financial products and services adhere to industry standards and regulations to comply with security and privacy assessments. This will include the use of innovative technology for advanced data encryption, fraud detection and prevention, multi-factor authentication, and firewalls, among others. FSPs must monitor and audit their processes and operations regularly. Additionally, they should invest in their staff’s training and capacity building to protect the customers against evolving risks and threats. These best practices will protect consumers against mis-selling and information asymmetry while they buy insurance.

- Timely service: Quick and timely customer service helps gain customer loyalty and trust. Customers feel more secure when they can rely on prompt support whenever needed. Proactively addressing concerns can mitigate the risk of negative reviews, complaints, or legal actions, which can impact the reputation of FSPs. Positive experiences with timely customer service can lead to favorable word-of-mouth recommendations.FSPs should ensure that customers have access to an intuitive and inclusive grievance resolution system that monitors and analyzes customer complaints, identifies risks and issues, and much more. FSPs can use AI to optimize internal processes, which will ensure customer complaints are efficiently directed to the right personnel for resolution. Effective use of supervisory technologies can help FSPs monitor customer complaints effectively and provide timely resolution.

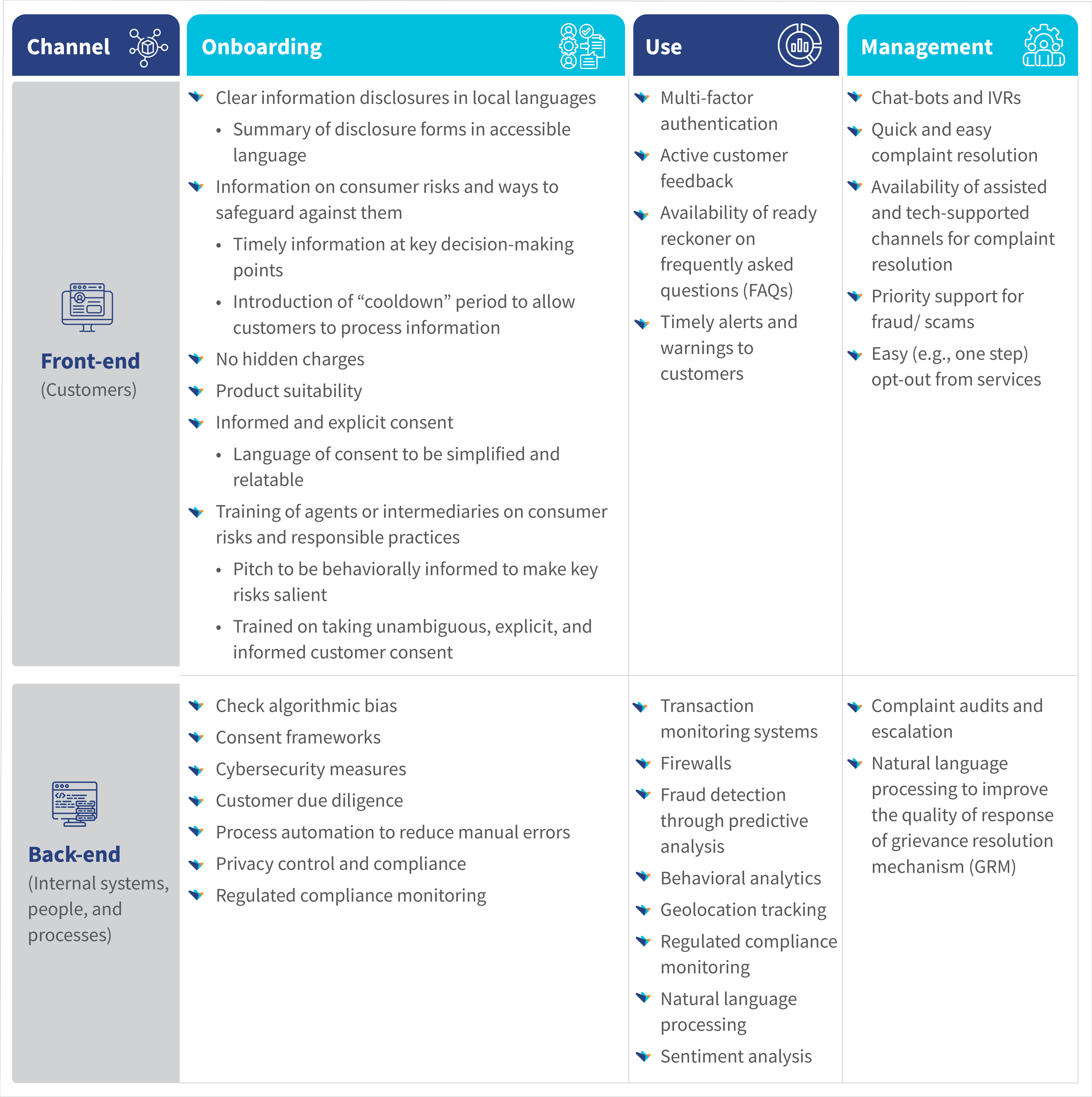

These five components play a crucial role to build customers’ trust and reinforce their protection. FSPs must ensure adherence to these principles at both the customer-facing front end and the internal systems, personnel, and processes on the back end of financial services.

Here is a checklist that FSPs can use to build trust, instill customer-centricity, and enhance protection at every stage of financial services delivery. These stages include customer onboarding, usage, transactions, and overall financial services management. The checklist directs FSPs to ensure trust and customer focus throughout their front-end and back-end processes and systems. This also covers functions that FSPs outsource to third parties and agents.

Explore the transformative approach that the Government of Bihar has undertaken to boost aquaculture in Bihar, through JEEViKA. This blog delves into how JEEViKA mobilizes women SHG-based fish farmer producer groups (FFPGs) and provides them with access to community ponds and water resources to take up aquaculture as a livelihood activity. This initiative has multiple gains, such as improved income and nutrition, increased access and control of women over community resources, and rejuvenation of water resources to tackle climate change. This initiative brings women to the forefront of a livelihood stream that has traditionally been a male domain.

Explore the transformative approach that the Government of Bihar has undertaken to boost aquaculture in Bihar, through JEEViKA. This blog delves into how JEEViKA mobilizes women SHG-based fish farmer producer groups (FFPGs) and provides them with access to community ponds and water resources to take up aquaculture as a livelihood activity. This initiative has multiple gains, such as improved income and nutrition, increased access and control of women over community resources, and rejuvenation of water resources to tackle climate change. This initiative brings women to the forefront of a livelihood stream that has traditionally been a male domain. UPI broke all records in August 2023. It observed 10.586 billion transactions that amounted to INR 15 trillion (~USD 189.64 billion). It has become the preferred payment choice for digitally-savvy Indians. However, it cannot reach the feature phone users. Its penetration is limited to urban segments with high usage of smartphones and mobile Internet. India is home to 400 million feature phone users. These users have limited avenues for digital transactions. They largely depend on physical access points for financial transactions. This blog discusses an innovative offline payment solution, UPI 123Pay, and its immense potential to bring digital payment convenience to the underserved segment.

UPI broke all records in August 2023. It observed 10.586 billion transactions that amounted to INR 15 trillion (~USD 189.64 billion). It has become the preferred payment choice for digitally-savvy Indians. However, it cannot reach the feature phone users. Its penetration is limited to urban segments with high usage of smartphones and mobile Internet. India is home to 400 million feature phone users. These users have limited avenues for digital transactions. They largely depend on physical access points for financial transactions. This blog discusses an innovative offline payment solution, UPI 123Pay, and its immense potential to bring digital payment convenience to the underserved segment. India’s farmers have had a long history of struggle. For decades, they have battled a multitude of agricultural challenges, such as fragmented landholding, numerous intermediaries, and low value addition. In response, the country has actively promoted farmer producer organizations (FPOs) as a solution. FPOs intend to address these serious issues through the aggregation of demand for high-quality inputs, credit, and technologies and the aggregation of outputs to improve smallholder farmers’ market access. Yet despite these efforts, major processors and output purchasing companies hesitate to engage directly with FPOs. This blog explains the options available for FPOs to trade with institutional buyers and the on-ground issues FPOs must overcome to establish better market linkages.

India’s farmers have had a long history of struggle. For decades, they have battled a multitude of agricultural challenges, such as fragmented landholding, numerous intermediaries, and low value addition. In response, the country has actively promoted farmer producer organizations (FPOs) as a solution. FPOs intend to address these serious issues through the aggregation of demand for high-quality inputs, credit, and technologies and the aggregation of outputs to improve smallholder farmers’ market access. Yet despite these efforts, major processors and output purchasing companies hesitate to engage directly with FPOs. This blog explains the options available for FPOs to trade with institutional buyers and the on-ground issues FPOs must overcome to establish better market linkages. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP) of India was published in the Official Gazette on 11th August 2023, after years of deliberations. This came after the Act passed both Houses of Parliament and received Presidential approval. This blog highlights the key provisions of the DPDP Act. Please note that many significant details about the implementation of the Act will be decided later by rules set by the Central Government.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP) of India was published in the Official Gazette on 11th August 2023, after years of deliberations. This came after the Act passed both Houses of Parliament and received Presidential approval. This blog highlights the key provisions of the DPDP Act. Please note that many significant details about the implementation of the Act will be decided later by rules set by the Central Government.

Behind Jakarta’s bustling business district, a small hawker skillfully prepares batagor, a beloved Sundanese delicacy. Customers form a queue and use

Behind Jakarta’s bustling business district, a small hawker skillfully prepares batagor, a beloved Sundanese delicacy. Customers form a queue and use