MGNREGA: The delay in wage payments – Part I

by Abhishek Jain

Apr 15, 2021

7 min

The Government of India (GoI) had introduced the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in 2005 to provide livelihood security to the rural poor. This blog examines the MGNREGA program and its accomplishments. It also provides an overview of the delay in wage payments to workers.

Introduction

Between 2011 and 2018, almost 32 million casual laborers[1] lost their jobs in rural India. Of these, 94% were farm jobs, which reflects the growing distress in the agriculture sector and rural economy of India.

At the time of the Socio Economic and Caste Census of 2011—India’s most recent census, 81% of the total households in rural India derived their income from either manual labor or cultivation.[2] Moreover, workers in rural India earn an average daily wage of INR 175 (USD 2.4),[3] which is less than half of what a worker in urban India earns—INR 384 (USD 5.2).

The Government of India (GoI) introduced Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), a social protection program to provide livelihood security to the rural poor, in 2005.

This blog, the first of a two-part series, examines the MGNREGA program and its accomplishments. It also provides an overview of the delay in wage payments to workers. In the second part of this series, we will look at the reasons behind the delay in wage payments and suggest ways to improve the efficiency of payments to optimize the impact of the program on India’s rural poor.

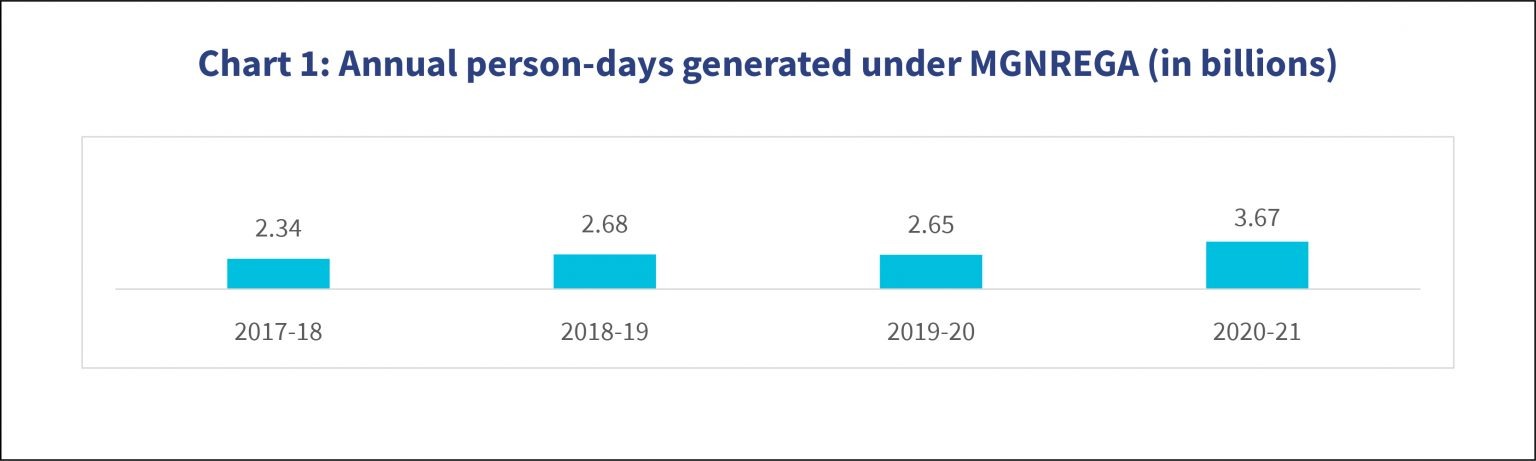

Under MGNREGA, the state (provincial) governments offer each household at least 100 days of unskilled manual work each year. The list of permissible works includes those related to agriculture, livestock, water conservation, and road construction, among others. People above the age of 18 who reside in rural areas[4] can register themselves and their family members at the gram panchayat (village council). The village council issues a job card to each registered household. As of 16th March, 2021, MGNREGA has 147.6 million active workers.[5] In 2017-20, an average of 2.55 billion workdays has been generated under the program per year. Whereas, 3.67 billion workdays[6] were generated in 2020-21 alone, as illustrated in chart 1.

(Source: Chart 1)

A rights-based framework under MGNREGA

With the existing wage disparity between urban and rural areas, and uncertainty around employment in rural India, MGNREGA has the potential to boost household incomes. The demand-driven program offers unskilled manual work to those who request it from their respective village council. The workers are employed within and around their villages and receive daily wages as per the rates determined by the Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD), GoI. The central government funds 100% of the wages for unskilled labor, as well as 75% of the material costs of projects sanctioned under the program. Conversely, state governments bear 25% of the material costs of projects and 100% of the unemployment allowance and delayed compensation. Moreover, state governments are permitted to claim 6% of the total labor budget for administrative expenses from the central government.

Through this rights-based framework, workers are entitled to employment within 15 days of requesting work. If the government fails to offer employment within this period, workers are entitled to receive an unemployment allowance.[7] Workers should receive wages within 15 days of completing work. Otherwise, they are entitled to compensation for the delay—0.05% of unpaid wages per day.

Shift from cash payments to direct benefit transfer

Before 2015, wages under MGNREGA were transferred to the bank account of the village council. Thereafter, members of the village council would distribute these wages in cash. This method was rife with inefficiencies, widespread corruption, payment to fake beneficiaries, and significant delays in payment. In 2014-15, 72% of the total wage payments saw a delay across India. As a result, the GoI switched from cash payments to direct benefit transfers (DBT)[8] to MGNREGA beneficiaries. DBT allowed the government to transfer the wages of workers directly into their bank or post office[9] accounts. DBT in MGNREGA was initially introduced in 2015 in 300 districts that had a strong penetration of banking infrastructure. The initiative was extended to the remaining districts across India in 2016.

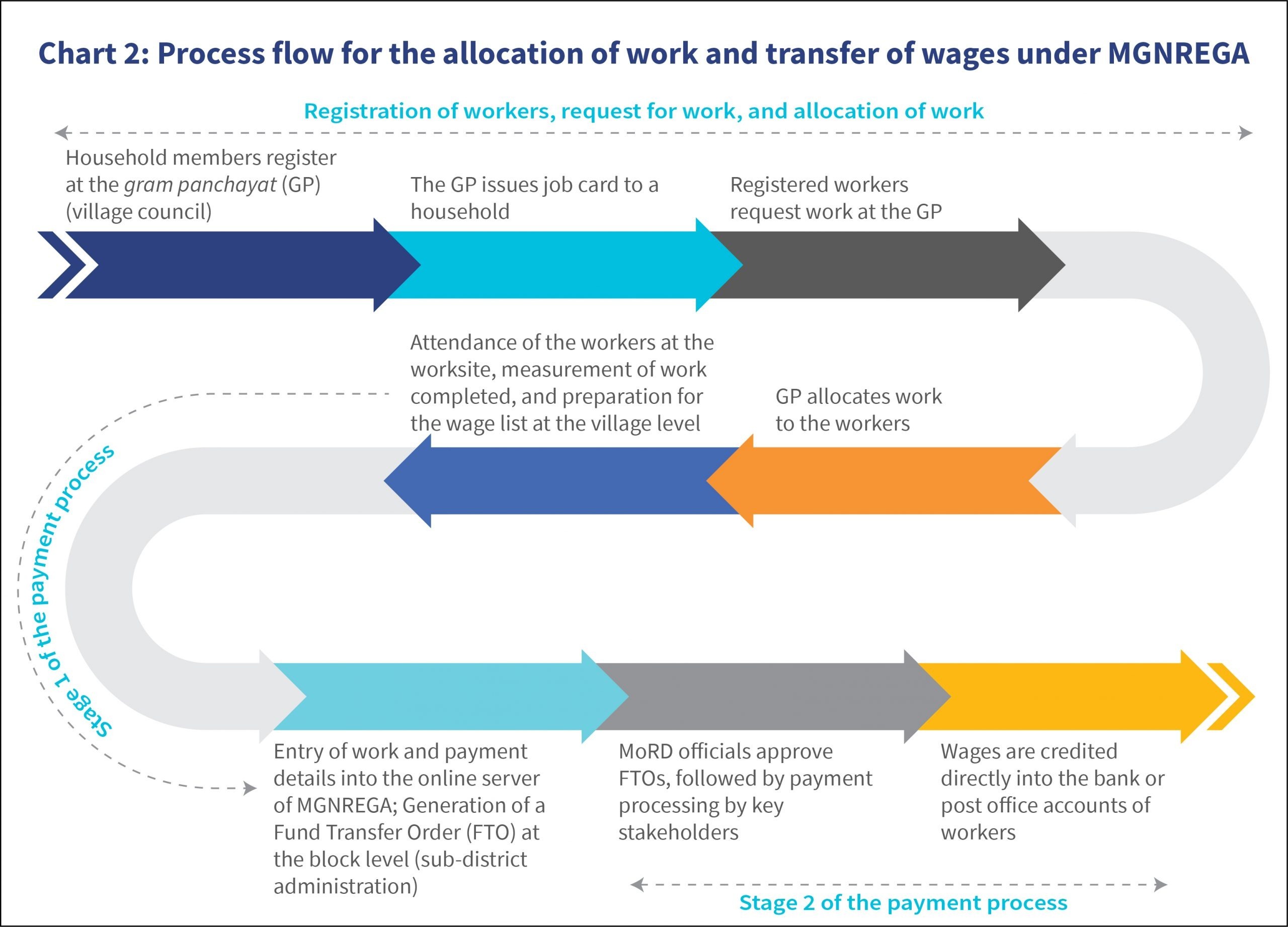

Further, to streamline the system of fund release between the GoI and respective states and union territories, India adopted the National Electronic Fund Management System (Ne-FMS)[10] in 2016. Distributing wages through Ne-FMS is a two-stage process, as illustrated below. In Stage 1, a fund transfer order (FTO) for the payment of wages is generated and approved on MGNREGA’s online server after completion of work at the block level (sub-district administration). In Stage 2, MGNREGA’s Program Division officials at MoRD approve the FTOs. The payments are then processed and credited into the respective bank accounts or post office accounts of the workers. Though the wage payments are required to be credited within 15 days of work completion, the Stage 1 processes should be completed within eight days from the date the beneficiary completes the work and the attendance sheet is closed. Meanwhile the Ne-FMS is designed to credit wages (Stage 2) ideally within two days of the approval of FTOs at the block level.

Delays in wage payment

The nationwide lockdown imposed in the wake of COVID-19 pushed the unemployment rate in rural India to over 20%. MGNREGA has been a lifeline for many amid the pandemic—between 1 April and 20 May during the lockdown last year, approximately 3.5 million households applied for registration under MGNREGA. Whereas, the total number of new applications in 2019-20 was only 1.5 million.

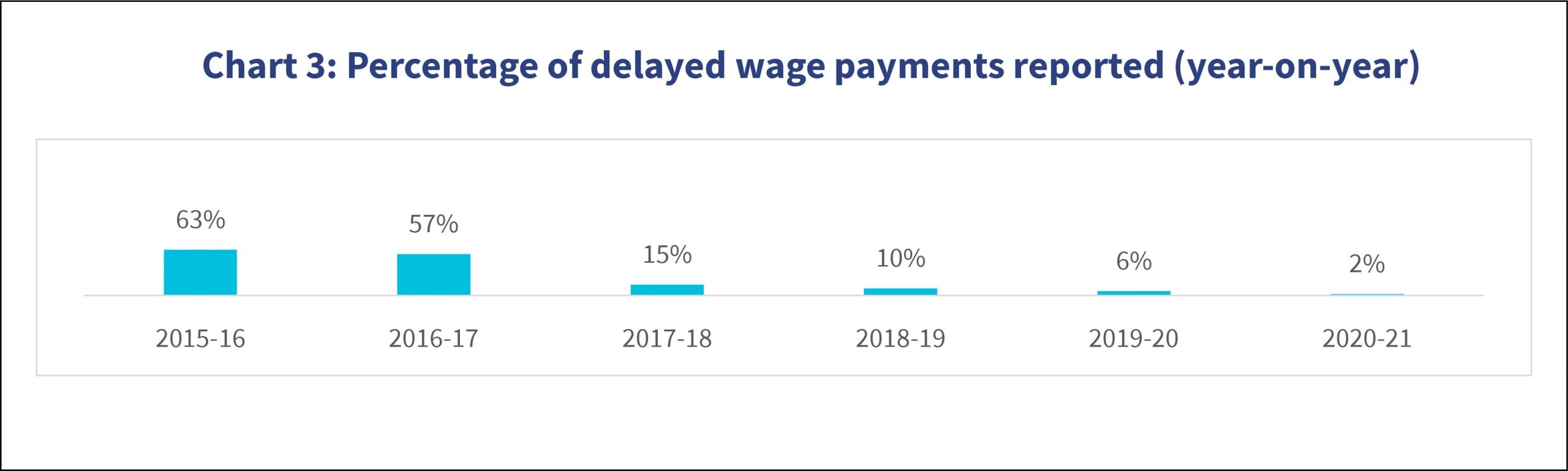

While almost all those who requested work in the past three years got employment, delays in the timely payment of wages remain a persistent issue. As of 16th March, 2021, about 2% of total wage payments were delayed in 2020–21. The delays in wage payments range from 16 to 90+ days. Around 11.3% of the total FTOs sent for payment processing through Ne-FMS (Stage 2 processes) in 2020-21 are still pending, which amounts to INR 74.36 billion (USD 1.01 billion). Of these, 88% of transactions from March, 70% from February, and 21% from January remain pending. Moreover, banks and post offices rejected 12.6 million (2.5%) and 66,350 FTO transactions (5%) respectively in 2020-21. This led to further delays or resulted in no payments for workers.

(Source: Chart 3)

According to an evaluation study MSC conducted across 18 states and union territories in 2020, 41% of the respondents registered under MGNREGA interviewed in Round 1 (April and May, 2020) had not received their wages. Moreover, only 53% of the respondents received work between May and July last year. Of these, 8% of respondents had not received their wages and 9% had received partial wages, as per Round 2 (August and September, 2020) of the study.

Since the implementation of DBT in MGNREGA, the timely payment of wages has increased reportedly from 37% in 2015-16 to 98% in 2020-21. However, according to an independent assessment of payment transactions in the first two quarters of 2017-18 across 10 Indian states, only 32% of wage payments were made within the stipulated period of 15 days, as compared to the government’s claim of 85%. This is because the government only considers delays caused under Stage 1 processes. The Department of Expenditure, Ministry of Finance, has acknowledged this flaw in the calculation. It has attributed the delays in Stage 2 to “infrastructural bottlenecks, unavailability of funds, and a lack of administrative compliance.”

Workers need wages to support and enhance their livelihoods. The timely payment of wages and correct calculation of delayed compensation is necessary to fulfill the legal entitlements of workers under the program. Hence, the government must identify and address the reasons behind the existing delays at various levels of the process.

MGNREGA came into being based on the need to provide for employment opportunities for the rural poor who struggle to find work and subsist on minimum daily wages. This rationale was laudable and continues to help keep millions of rural Indians economically afloat. However, delays in wage payments must cease to ensure beneficiaries receive their compensation on time to meet their livelihood obligations. In the second part of this blog series, we will look at the causes of delayed payments and ways to alleviate process inefficiencies so the MGNREGA program can have an optimal impact.

[1] Casual laborers refer to individuals employed periodically according to the demand for work.

[2] The Census is a population enumeration exercise conducted in India each decade by the Registrar General of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, GOI. The 2011 Census is the latest for which data is available, with the next census planned for 2021.

[3] A conversion rate of 1 USD = INR 73.3 has been used throughout the blog (as on 3rd March, 2021)

[4] Under MGNREGA, “rural area” refers to all areas within a state except those covered by an urban local body or a Cantonment Board established or constituted under the laws in force at the time.

[5] Active workers refer to any individual of a household who has worked for at least a day in the last three financial years.

[6] The data from the MGNREGA MIS used throughout the blog is as reported on 16th March, 2021, unless specified otherwise.

[7] Under MGNREGA, if the village council is unable to offer work to workers within 15 days of their request, the state government is responsible for paying an unemployment allowance, which ceases as soon as work is allocated according to the provisions in the regulations.

[8] Direct benefit transfer (DBT) is a program launched by the Government of India to transfer benefits and subsidies of various social welfare programs directly into the bank accounts of beneficiaries.

[9] Post office accounts are banking services offered by the Department of Post, GoI. These accounts can be mapped with the beneficiary’s Aadhaar number, linked to their MGNREGA job cards, and used to receive their MGNREGA wages through DBT.

[10] Ne-FMS is presently implemented across 28 states and UTs in India, which enabled them to receive funds under MGNREGA from the central government. The remaining states and UTs use the electronic Fund Management System (e-FMS)—Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, Goa, Lakshadweep, Manipur, and Nagaland.

Written by

by

by  Apr 15, 2021

Apr 15, 2021 7 min

7 min

Leave comments