Locally-led adaptation to climate change: Can digital technologies help?

by Graham Wright and Aarjan Dixit

Feb 6, 2024

6 min

Climate change demands urgent action. As per a World Bank report, 80% of the global population most at risk from crop failures and hunger from climate change are in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Crop production in South Asia is expected to decrease by 30% by the end of this century. This blog identifies digitally-enabled locally-led adaptation as a key solution to combat the devastating impact of climate change. Read on to learn why we must accelerate the development, financing, and implementation of locally-led adaptation plans and how digital technologies can scale up such LLA initiatives.

“Farming has become such a lottery now that the weather gods are no longer our friends. Everyone in the village has sent their sons away to earn in the city—we have no other way to make ends meet,” sighs Krishna Lal as he laments that “Everything has changed.”

Climate change requires urgent action

Farmers’ income and asset bases are being remorselessly eroded by the impact of climate change, as highlighted in this brief but startling video. Worldwide, farmers, such as Krishna Lal, are already struggling to respond to these issues.

Climate change events impact smallholder farmers in direct and indirect ways. Firstly, extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, floods, and droughts, threaten smallholder farmers, particularly in regions where rain-fed agriculture is prevalent, such as Africa, Asia, and Latin America. These events can lead to crop failure, reduced yields, and loss of income, which affect food security. Additionally, changes in temperature and precipitation can impact livestock and reduce feed quantity and quality, and water availability, which further exacerbates the challenges of smallholder farmers. Moreover, changing growing seasons and the prevalence and dispersal of pests and diseases present additional challenges for farmers.

Climate change will continue to affect food production worldwide. As per a report by the World Bank, 80% of the global population most at risk from crop failures and hunger from climate change are in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Crop production in South Asia is expected to decrease by 30% by the end of this century. The World Bank report highlights that the most vulnerable populations are those who are already poor and depend on agriculture for their livelihoods.

In response, we must accelerate the development, financing, and implementation of locally-led adaptation (LLA) strategies to support community-based efforts and increase the ability of millions of farmers to respond to the rapidly changing climate and the resulting extreme weather patterns. These LLA efforts must be hyperlocal to respond to climate impacts that vary across different communities.

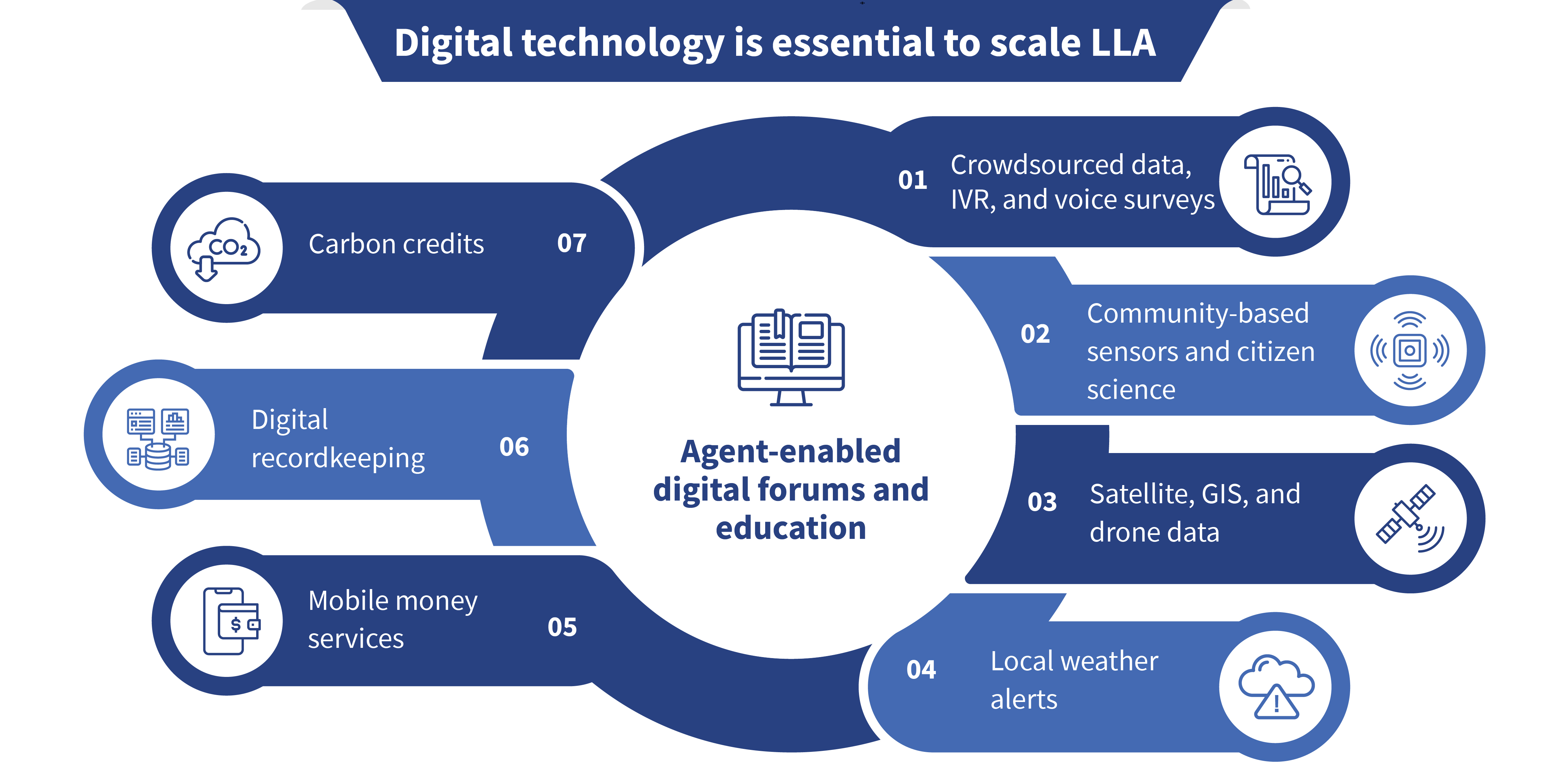

Digital technologies can facilitate, speed up, and scale LLA planning and the governance functions of monitoring, evaluation, and learning to refine and optimize adaptation initiatives. These technologies can provide various benefits, such as easier and real-time access to information, peer-to-peer information exchange, digital recordkeeping, performance-based payments and carbon credits, and the integration of scientific data and analytics into local plans. As the Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRAg) working group of the CIFAR Alliance notes, digital solutions in various forms can also significantly improve market functioning and the delivery of productivity-enhancing solutions for farmers. These technologies open up new pathways for the adaptation and transformation of agri-food system value chains. Furthermore, many of these technologies are already available but remain hopelessly underused.

Agents as gateways to the digital world and catalysts of change

About 16% of the global adult population lacks access to a mobile phone. For the foreseeable future, 409 million men and 440 million women lack access to basic feature phones, let alone smartphones. As such, we need alternative approaches to ensure they can access digital services and thus provide the data to train algorithms and large language models. Cash-in and cash-out (CICO) agents used by mobile money service providers and banks to deliver financial services can play a pivotal role in the transition of underserved communities to Internet or app usage. They can act as mentors to promote this shift.

Despite previous concerns around over-the-counter transactions (OTCs), agents are still indispensable in the onboarding of excluded and inadequately served demographics, which include women—particularly if female agents are deployed. Agents guide individuals—especially those from poor communities—through the digital landscape, help oral or less confident users, recommend suitable apps, products, and services, and demonstrate the use of data-enabled services.

The use of agents in this capacity enables shared hardware and allows assisted, on-demand Internet access without the need to buy bulk data. Thus, it grooms future generations of smartphone users. Investments are crucial to establish profitable models that incentivize agents to offer these essential services.

Likewise, microfinance institutions’ (MFIs) staff and agricultural extension agents (AEAs) can be catalytic to promote the development of LLA strategies and plans. MFI staff’s involvement can also ease the collection of data and promote a better understanding of credit risks associated with lending to climate-impacted communities to facilitate lending to these communities. AEAs can provide technical inputs into the rural communities’ adaptation plans, which can strengthen their strategies to respond to climate change along agri-food value chains.

Digitally-enabled locally-led adaptation

CICO agents, MFI staff, and AEAs in climate change-vulnerable areas can emerge as nodal points to help community-based organizations develop LLA plans. With Internet access, they can provide inroads to key data and insights for the participatory planning process and then ease the management and governance to implement these plans.

This would entail these agents being reinvented and incentivized as “catalysts of change,” who would use and facilitate access to various digital technologies for underserved communities. These technologies can be deployed to support and scale LLA planning and monitor the implementation of those plans for performance-based payments. AI-enabled online forums in local languages can offer opportunities for communities to share knowledge, discuss challenges, and co-create adaptation strategies. Mobile platforms can be used to deliver educational content on adaptation practices suitable for local conditions.

As adaptation plans are implemented, local language weather apps, such as TomorrowNow, can be used to provide communities with essential alerts on imminent weather changes, which would enable them to prepare and respond better. Mobile money services can be used to deliver funds in a transparent and efficient way for adaptation projects. Moreover, digital recordkeeping can ensure the accountable use of resources and create important digital trails that promote lending by formal financial service providers. In addition, digitally enabled carbon credit tracking and trading platforms, such as CaVEx, can allow farmers to receive financial support for their adaptation.

Digital technologies can help monitor and govern the implementation of adaptation plans and enable smart contracts to reward the achievement of performance goals. Communities can report progress and challenges in real time through community-based and operated sensors, satellite and drone services, and feedback platforms, and provide insights and recommendations to improve adaptation initiatives and local and national climate adaptation policies.

A focus on accessible and practical digital technologies for rural communities and the agents that serve them can significantly enhance LLA strategies’ effectiveness. However, these digital tools must be aligned with the local context, language, and needs, to foster community participation, knowledge sharing, and sustainable adaptation practices. Particular care must be taken to ensure the poorest and most vulnerable people are encouraged and enabled to participate in the planning and monitoring exercises.

Although untested, we believe that agents’ involvement in LLA planning can offer them additional revenue streams and provide real use cases for poorer, vulnerable people in remote communities. This can help often excluded vulnerable people start their journey into the digital world and deliver data to inform and train AI tools. These LLA-driven use cases provide us with opportunities to offer tangible value to these hard-to-reach communities, increase their resilience, and show them the benefits of digital tools. Many vulnerable communities comprise smallholder farmers who can benefit from digitally-enabled value chains and financial services. Climate change and the LLA response to it can bridge the digital divide for these farmers and others currently stranded in the analog world—if we encourage and enable it.

Want to learn more? See the CIFAR Alliance locally-led adaptation whitepaper.

Written by

Graham Wright

Group Managing Director

by

by  Feb 6, 2024

Feb 6, 2024 6 min

6 min

Leave comments