Is the non-exclusive agent network model paying off in Senegal?

by Melissa Rousset

May 31, 2016

5 min

The Helix Institute’s Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Senegal country report, indicates that high levels of non-exclusivity (66%) among Senegalese agents offering competing products brings a great diversity of actors in a booming market. This blog looks at some of the advantages and challenges of the non-exclusive agent network model in this market.

The diversity of players

The Senegalese digital finance market is fractured between four major players. Wari is the market leader—in terms of its presence of agents—representing a little over a third of agents in the country (34%), but it certainly does not dominate the digital finance space. Joni-Joni, a third-party provider that launched in 2013, accounts for a quarter of the market presence, followed by two mobile network operators (MNOs) Orange (20%) and Tigo (11%). Financial institutions are thus far not as widely represented in the Senegalese agent network, as Microcred’s and Manko’s share of market presence is less than one percent each. However, this could change. Senegalese financial institutions can take their lead from Kenyan banks that have impressively increased their share of market presence from five percent to approximately 15% between 2013 and 2014, and offer additive—not competitive—services to the existing product suite.

The diversity of players observed in the Senegalese market is rare among ANA markets and is only comparable to Zambia where five major players –MNOs, financial institutions and third-party providers – are vying for a piece of the pie. This diversity is really a key difference between Senegal and leading East African markets such as Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. In these markets, MNOs dominate the landscape most likely because they were able to leverage heavily on their existing distribution network and customer base and thus aggressively grow their market presence first, creating a higher barrier to entry to other players. However, in Senegal, MNOs did not initially leverage their distribution network which cleared the path for third party providers to embark on their journey quite successfully.

Figure 1. DFS Providers’ Market Presence of Agents

The power of non-exclusivity

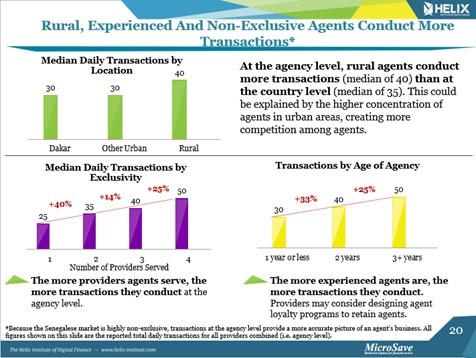

Senegalese agents serve a median of three providers. In fact, the more providers an agent serves, the more transactions they conduct at the outlet level (figure 2). Senegalese agents conduct comparable transaction volumes to the leading East African markets, with a median of 35 daily transactions at the agency level.

Figure 2. Median daily transaction volumes by Exclusivity

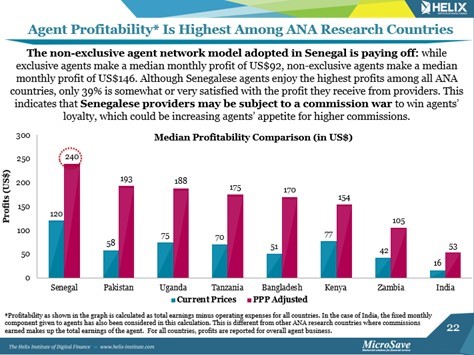

Not only do agents perform higher levels of transactions when they serve multiple providers, but they also earn higher profits. While exclusive agents make a median monthly profit of US$92 (PPP adjusted), non-exclusive agents make substantially more – a median monthly profit of US$146 (PPP adjusted), as the latter are able to diversify their revenue streams without increasing their operating expenses. Because most agents are non-exclusive in Senegal, they make the highest profits among all ANA research countries (figure 3).

Figure 3. Outlet Profitability among ANA Research Countries

Quite interestingly, ANA Senegal demonstrates that over time, agents actually tend to serve more providers. Given the recently issued regulation prohibiting providers to impose exclusivity, transactions and profit levels will most likely keep increasing at the outlet level along with non-exclusivity levels in the near future.

The challenges of non-exclusivity

In Senegal, providers rely on a profitable and dynamic agent network. However the stiff competition we witness at the outlet level means that providers will have to maintain a competitive edge at the agent level, while at the same time ensuring their products are pushed out.

Commission war: in a non-exclusive OTC market, agents have the ability to select which provider they conduct transactions for. This power dynamic puts providers under pressure to offer outstanding agent support and/or loyalty programmes, often in the form of monetary incentives, in order to motivate agents to sell their services and lure new customers to their network. This can inflate the commissions that agents receive from competing providers, and thus also have the adverse effect of increasing an agent’s expectation of their future profits. In fact, only 39% of agents are somewhat or very satisfied with the profit they receive from providers, despite being the most profitable—at the agency level—among ANA countries. This perceived expectation is a challenge that providers will need to tackle.

Ripple effect on tariffs: an agent’s increased commission translates to a steady decrease of a provider’s own margin. If providers keep investing a higher percentage of their revenues back into agent commissions, then this will likely impact cash-in and cash-out transaction fees paid by customers down the line. In a competitive market like Senegal, one in which providers are offering similar products, providers will not want customers to bear the brunt of the commission war and ultimately hurt the expansion of DFS in the country.

Quality of support: in addition to providing agents with monetary incentives, a provider’s ability to win an agent’s loyalty can hinge on the quality of service they offer. However, ANA Senegal data shows that providers have not yet succeeded in delivering efficient support systems – only one-third of agents receive regular monitoring visits. This means two things – firstly, that providers are unlikely to ensure agents are well informed, satisfied and provide a high quality of service to customers; and secondly that providers are blind to many aspects of how their agents operate, as well as what competitors are doing in the area. Improving on these aspects will help providers maintain a competitive edge over other players.

Now what?

The non-exclusive agent network model is paying off in Senegal: Senegalese agents make high levels of transactions and profits, which is typical of a competitive market in which each provider tries to stand out. As competition grows though, providers could consider the following strategies to ensure their competitive advantage—among both agents and customers: 1. Shift competition from the agent level to the product level. This can be achieved by designing a compelling value proposition that meets customers’ needs and preferences; 2. Collaborate on support services to improve the quality of support given to agents.

In our upcoming blog on the Senegalese market, we will examine the innovative approaches providers have employed to stimulate customer usage and draw on lessons learnt from other markets in East Africa and South Asia.

Sabine is a Country Technical Specialist, responsible for the implementation of the United Nations Capital Development Fund Mobile Money for the Poor (MM4P) Digital Finance country strategy in Senegal, Benin and Liberia. In this role, she collaborates with diverse stakeholders – regulators, governments, digital financial services providers – to accelerate the development of digital finance ecosystems and make financial services accessible to the low-income population, women and rural households.

by

by  May 31, 2016

May 31, 2016 5 min

5 min.jpg)

Leave comments