Indian agriculture during and after the pandemic

by N. Srinivasan, Venkatesh Tagat and Girija Srinivasan

Jul 20, 2020

Jul 20, 20207 min

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, agricultural activities in India were exempt from restrictions. However, the lockdowns led to various disruptions in the supply chain. This blog summarizes the impact of COVID-19 on different sub-sectors and highlights the measures the government took to address the problems of farmers.

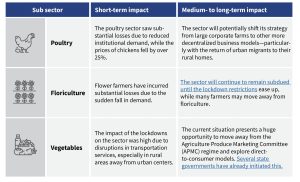

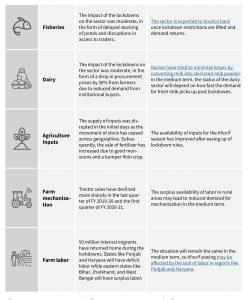

Impact of COVID-19 on agriculture

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, agricultural activities related to production and marketing have been deemed “essential services” and were not restricted in any state. However, the lockdowns shut the operations of retail sellers and restricted their movement, constrained the movement of goods severely, closed processing units that consume agricultural commodities, and—despite their essential service tag—shut down some mandis and markets. As the country begins to open up again, we summarize the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the different sub-sectors and look at the ones that are in a position to bounce back and the ones that will continue to struggle.

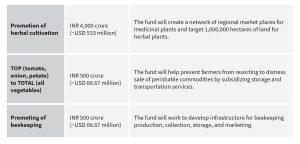

The Government of India (GoI) and many state governments have designed several measures to address the problems that farmers face. The GoI has announced the following measures[1]

The GOI has also taken a few important policy decisions, including:

- Amendments to the Essential Commodities Act to deregulate the stock limits and prices of commodities like cereals, edible oils, pulses, onions, and potato to allow farmers to realize better prices

- Agriculture marketing reforms to remove restrictions and allow farmers to sell to any buyer of their choice in any geography, including through electronic market platforms—thereby diluting the monopoly of the APMCs

However, the payments under the PM Kisan Yojana alone, which reaches about 85 million farmers out of a potential beneficiary base of 140 million, is likely to provide immediate relief and food security. All other measures will only reach or have an impact on the farmers in the medium to long term. One new measure is the INR 1-lakh-crore fund (~USD 13.3 billion) for agricultural infrastructure. The response from the government shows that it is sensitive to the problems in the farm sector but has been unable to define the nature of the complex challenges precisely. It has therefore adopted an approach akin to “a rising tide will lift all boats” in its measures. However, not all vulnerable farmer households have “boats”.

Three key issues that have emerged in the post-COVID-19 era

Agriculture finance

Finance for agriculture from formal financial institutions has been growing steadily year on year for the past 15 years. The ratio of agri-credit outstanding to agri-GDP increased from 13.34% in 2003 to 51.56% in 2017-18. This was largely due to efforts like the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) program.[2] By the end of March, 2020, the outstanding agricultural credit was INR 11.69 lakh crores (~USD 155.9 billion). However, this seemingly large sum constitutes only 12.5% of the gross bank credit in India. The share of bank credit for agriculture continues to remain less than agriculture’s share in the GDP (16.5%). According to the financial inclusion survey carried out in 2015-16 by NABARD (NAFIS), 38% of the farm households surveyed depended on non-formal sources of finance, with 30% relying exclusively on informal sources. Unsurprisingly, small and marginal farms depended more on informal sources of finance.

One of the problems that have emerged recently is credit for the Kharif season. With more than 30 million farmers who have received a moratorium on loans until August, 2020, the prospects for securing Kharif crop loans do not look bright. Banks rarely provide a second loan when an earlier one is outstanding. Once the lockdowns lift, banks will busy recovering loans that come out of moratorium and processing new proposals under the different packages—the loans for Kharif season are unlikely to get priority.

The merger of a large number of public sector banks coupled with the uncertainties regarding staff placements in the branches will add to the problems of a significant number of farmer customers. Stakeholders need to find solutions to these problems and develop simple systems to provide Kharif loans. For example, in Maharashtra, the state government has provided a guarantee[3] for the repayment of outstanding loans of farmers, paving the way for the disbursement of new Kharif loans. Similar initiatives are required in other states to increase and simplify the flow of credit.

Women in agriculture

The Government of India in the Economic Survey (2017-2018) stated that the agricultural sector in India is undergoing feminization. Even though women only own 12% of the total agricultural land, over 73% of rural women workers have found employment in agriculture.[4] In the face of shrinking employment opportunities in agriculture, men have diversified into the rural non-farm sector, while male out-migration has emerged as a major livelihood strategy.

The World Bank estimates that India has more than 140 million internal migrants.[5] With fewer non-farm sector jobs available and reverse migration of men back to villages, more men will be available to take up agriculture. An estimated 50 million inter-state migrant laborers have returned to their villages from cities after the nationwide lockdown. This could affect women’s standing as farmers and risk reversing the gains achieved over the past decade.

With men back in the villages, women may be pushed to undertake the least paid and most menial agricultural tasks. Their wage rates may dip further. As men are now locally present, they may get more involved in the marketing of their produce and thus control the money. Women’s self-help group (SHG) networks and NGOs will have to play a larger role in negotiating space for women. Anecdotal evidence continues to suggest that SHG members have been supporting each other by exchanging labor on the lines of Pragathi Bandhu groups promoted by Shree Krishan Dharmastala Rural Development Project (SKDRDP)[6].

SHG federations and village organizations could also play a larger role in arranging for the supply of inputs and ensure aggregation and marketing of produce. The women FPOs promoted by State Rural Livelihood Missions (SRLMs), such as JEEViKA in Bihar, have also been leading the way in developing farm-to-fork models for women farmers to market commodities. Civil society organizations and governments should organize suitable capacity-building activities to help women retain their space. Work allocation under NREGS should also give adequate representation to women.

Farmers’ Producer Organizations (FPOs)

The dilution of APMC and the ECA opens up exciting market opportunities for FPOs. If all states align their policies with the central government’s ordinance, then this can unshackle the buyers and allow them to purchase from anywhere—which in turn means more choice for farmers. Several large corporates, such as Godrej and ITC have also shown an increasing preference to trade with farmer collectives than the traders on whom they have traditionally had to rely on. The bargaining power of farmers or FPOs will increase as they are not required to sell within a specific geography.

The recent focus on setting up 10,000 FPOs is well-intentioned. How FPOs have responded during the pandemic and lockdown has been a revelation for farmer members as well as for other stakeholders. However, many dormant FPOs exist in the system and the investments made in their formation remain idle. As a first step, it would be useful to examine the operations of the 7,300+ registered FPOs and design interventions and assistance to help dormant and sub-optimal ones realize their full potential.

The increased confidence of corporates in FPOs has enhanced the scope for contract farming and improved corporate tie-ups. However, to ensure that all parties uphold contract terms, it is necessary to frame contracts to incorporate insurance-based safety-net provisions, as well as provisions that allow farmers to share any unexpected gains due to market buoyancy. It is equally important to set-up dispute resolution mechanisms in the form of arbitration bodies at the district or sub-district levels, which are easy and cost-effective for both farmers and contracting entities.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis has bought to the fore some of the persistent problems that Indian agriculture faces. Despite the impressive strides made toward improved access to institutional credit, dependency on informal credit sources remains high, especially among smallholder farmers. The government has to step in to ensure farmers can access fresh credit for the Kharif season. The other important dynamic that policymakers and the wider development community need to look at is preserving the role of women in agriculture. The surplus labor in rural areas can potentially undermine the status of women in agriculture, and push them further into economic exclusion.

The SHG movement that includes SHG federations and women-owned FPOs should be utilized to improve market price realization for women farmers and improve the engagement of women in value-addition activities such as low value processing. The push for market reforms has put the focus on the transformative role of FPOs in agriculture marketing. The dilution of the ECA and APMCs provides a huge opportunity for FPOs to link directly with buyers across the country and also to develop more direct-to-consumer supply chains, and in the process, improve their incomes.

[1] USFDA: COVID-19 in India – GOI’s Economic Package for Self-Reliant India – Food and Agriculture Items

[2] RBI: Report of the internal working group on agriculture credit (2019)

[3] The government has given clear directions to banks to note pending loans as “to be paid by the government” and to not consider farmers as defaulters.

[4] https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1518099

[5] World Bank. 2020. COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens. Migration and Development Brief No. 32;. World Bank, Washington, DC. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33634 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.”

[6] Developed by SKDRDP, “Pragathi Bandhus” are unique models of male-member self-help groups that center around the cultivation of waste and fallow lands through labor sharing. Such groups organize and empower small and marginal farmers and laborers through the transfer of governance to the village level.

by

by  7 min

7 min

Leave comments