India: From “laggard” to leader – what a journey!

by Graham Wright

Jan 31, 2024

6 min

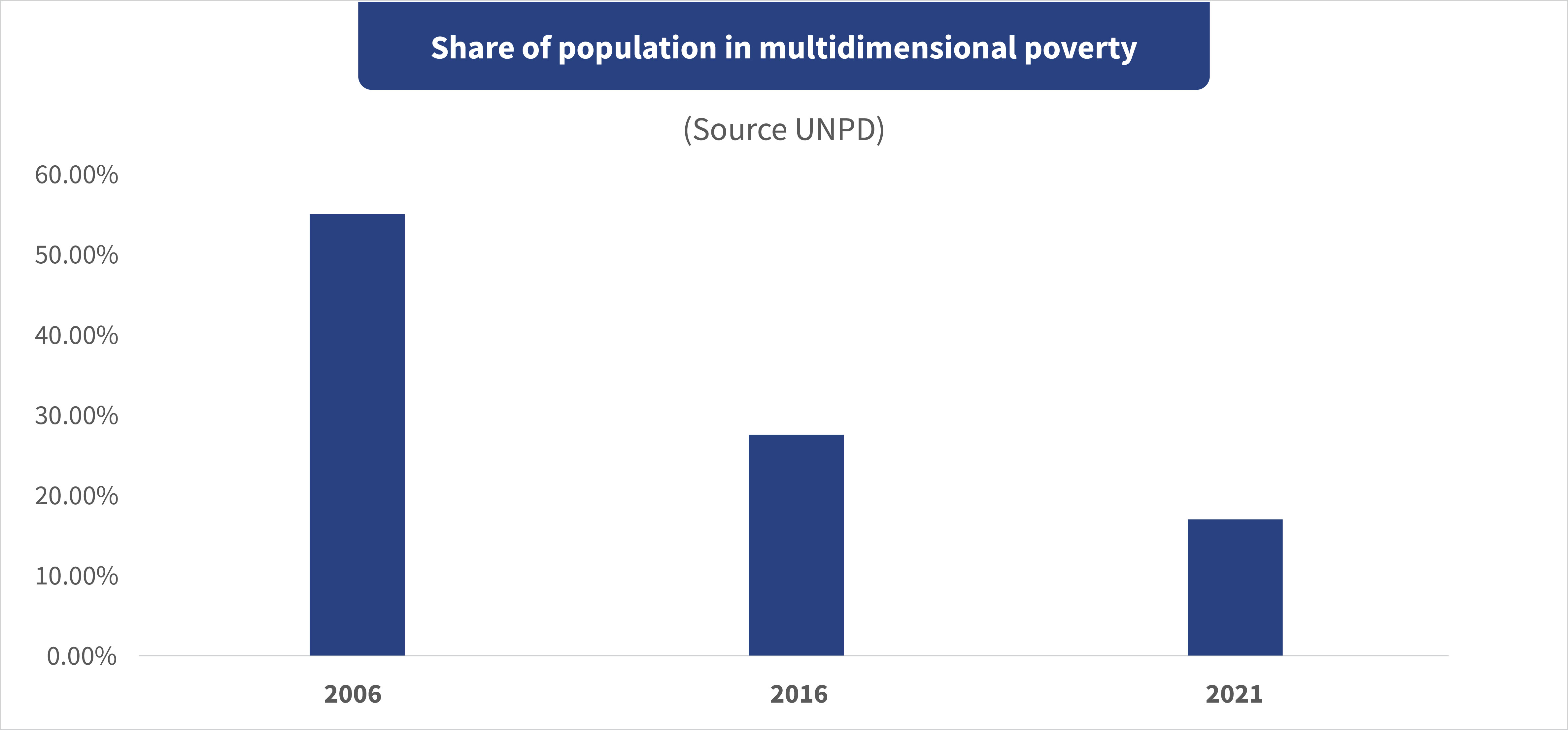

This blog charts MSC’s 25-year journey in India as we trace its roots to the founder’s fascination with the country back in 1989. It delves into the evolution of financial inclusion models in India, MSC’s involvement in various microfinance initiatives since 2005, and its pivotal role in the adaptation to the changing landscape of digital financial inclusion. The blog highlights MSC’s contributions across various sectors, such as technology, agriculture, health, and education. It emphasizes the organization’s socioeconomic impact, as evidenced by the reduction in multidimensional poverty.

India has always been unique and special in so many ways—including the challenges and solutions for the effective financial inclusion of its huge population. In 1989, after I left my home in Bangladesh, I spent seven of the happiest and awe-inspiring months of my life on a visit to India for less than USD 10 a day, which included the costs of all the train and bus fares. I traveled from Darjeeling to Amritsar, from Leh to Kanyakumari, marveling at the sights, sounds, and kindness of those I met. This trip was the culmination of years of a profound, inexplicable obsession with India that started well before I knew anything of reincarnation. And it only fueled the fires of my passion for the country, its people, geography, history, and cultures.

Amid the joy and excitement, I often came face to face with old Bharat. I waited for an entire day for my turn to call my parents from a post office in the hills of Himachal Pradesh. I spent five hours trailing from counter to counter to fill out a series of old multi-column ledgers in a hot and dusty bank branch in Puri on the Odisha coast to cash some travelers’ cheques.

After years in the remote mountains of the Philippines and in Kenya, I returned to India in 2004 on a mission to assess if the market-led approach of MicroSave (now MSC) could add value to the new joint liability group-based microfinance institutions. How India had changed and yet remained the same. Liberalization had transformed the cities, while the villages remained exactly as they were.

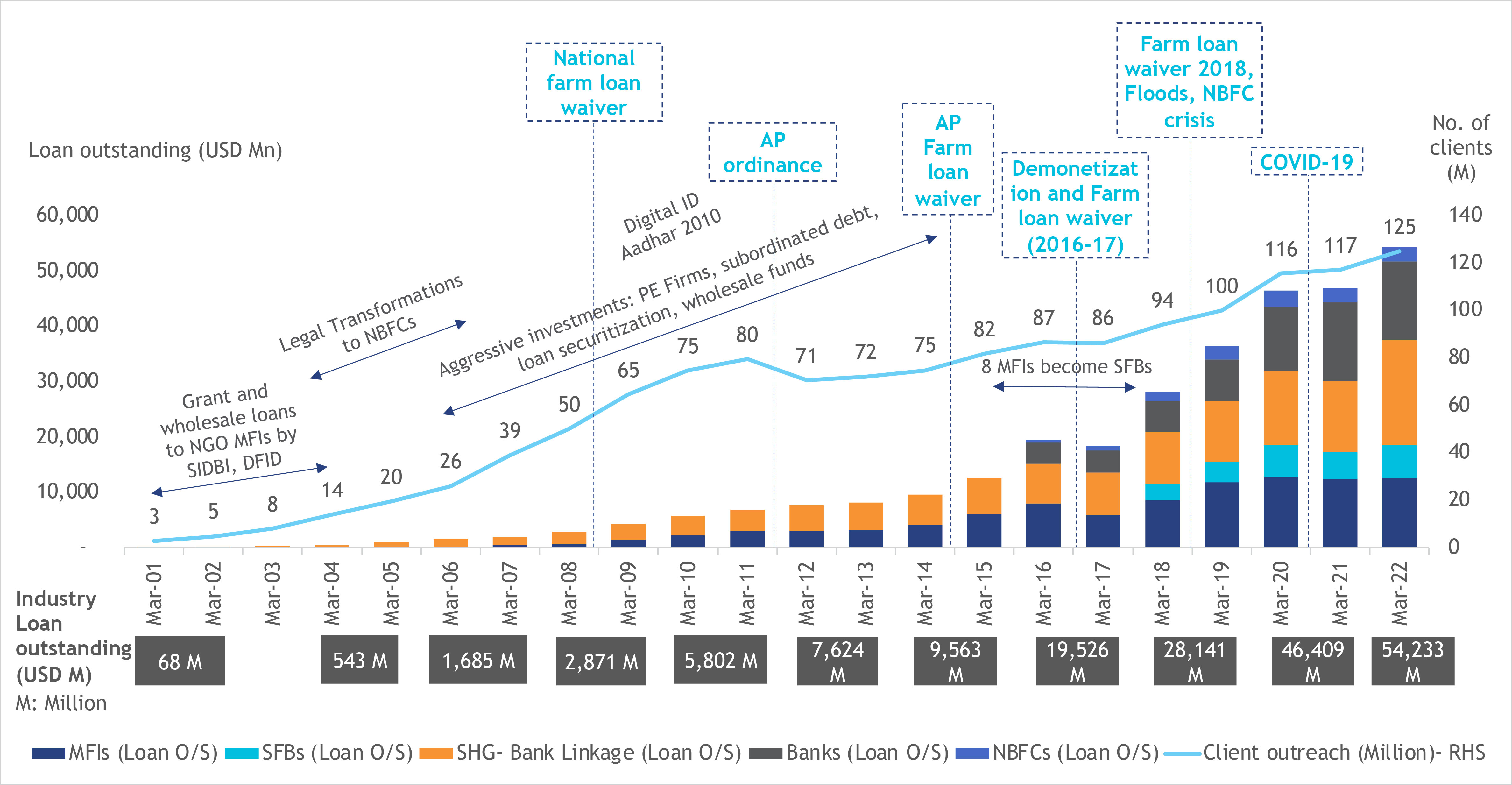

While much of the world followed the Grameen Bank model of joint liability groups (JLGs), India charted its own course. The country’s unique approach to financial inclusion started with visionary NGOs, such as MYRADA and PRADAN. Within a few years, the Government of India saw the potential of the self-help group (SHG) model and moved to support and scale it through NABARD, which launched the SHG Bank Linkage Programme (SBLP) in 1992. Senior NABARD officials who were kind enough to meet me in 2004 assured me that India had solved the problem of getting financial services to poor people with SHGs.

Yet despite such optimistic claims, other models emerged from SEWA, BASIX, and many organizations influenced by the JLG model’s success across the border. Another government agency played a crucial catalytic role in the growth of these microfinance institutions (MFIs). SIDBI’s Foundation for Micro Credit was led by Brij Mohan, who provided invaluable support to the growing movement. By 2004, it was clear that microfinance was set to revolutionize financial services for poor people in India.

Powered by the Reserve Bank of India’s priority sector lending requirements, both SHG- and JLG-based models were poised for rapid expansion and, in many cases, competition for the same clients.

MSC started operations in India in late 2005 with support from ICICI Bank and the Institute for Financial Management and Research, with the outstanding Manoj Sharma at the helm. We were just in time to:

- Support a consortium of banks that lent to MFIs with loan portfolio audits;

- Run strategic business planning workshops for many of the leading MFIs, including Bandhan, Spandana, and Grameen Koota;

- Nurture and grow more than 20 nascent MFIs in the country’s underserved remote rural areas for the ABN Amro Bank Foundation;

- Train hundreds of senior management executives of MFIs and banks on a range of key issues, which included market research, product development, process analysis, risk management, staff incentive schemes, and strategic marketing;

- …and to predict and help respond to the Andhra Pradesh crisis.

In 2012, MSC won the HSBC-ACCESS Microfinance Award for Support Organizations, which Manoj and I received at the Access Inclusive Finance India Summit in Delhi. This meant a huge amount to the MSC team—we pulled them all into our Lucknow conference room for celebrations and passed the trophy around from hand to hand in thanks to everyone on the team who had put so much energy and effort to make us worthy of the recognition.

However, one of the key attractions of coming to India was its technological prowess. In Africa, MicroSave helped beta test the M-PESA mobile money solution. And indeed, I served on the original M-PESA Steering Committee. This experience gave me a clear vision of the future, and I was quite sure that India would be the first to realize its full potential. At my first Access Inclusive Finance India Summit, I met several thought leaders who worked on digital solutions, including Samit Ghosh of Ujjivan and Abhishek Sinha of Eko.

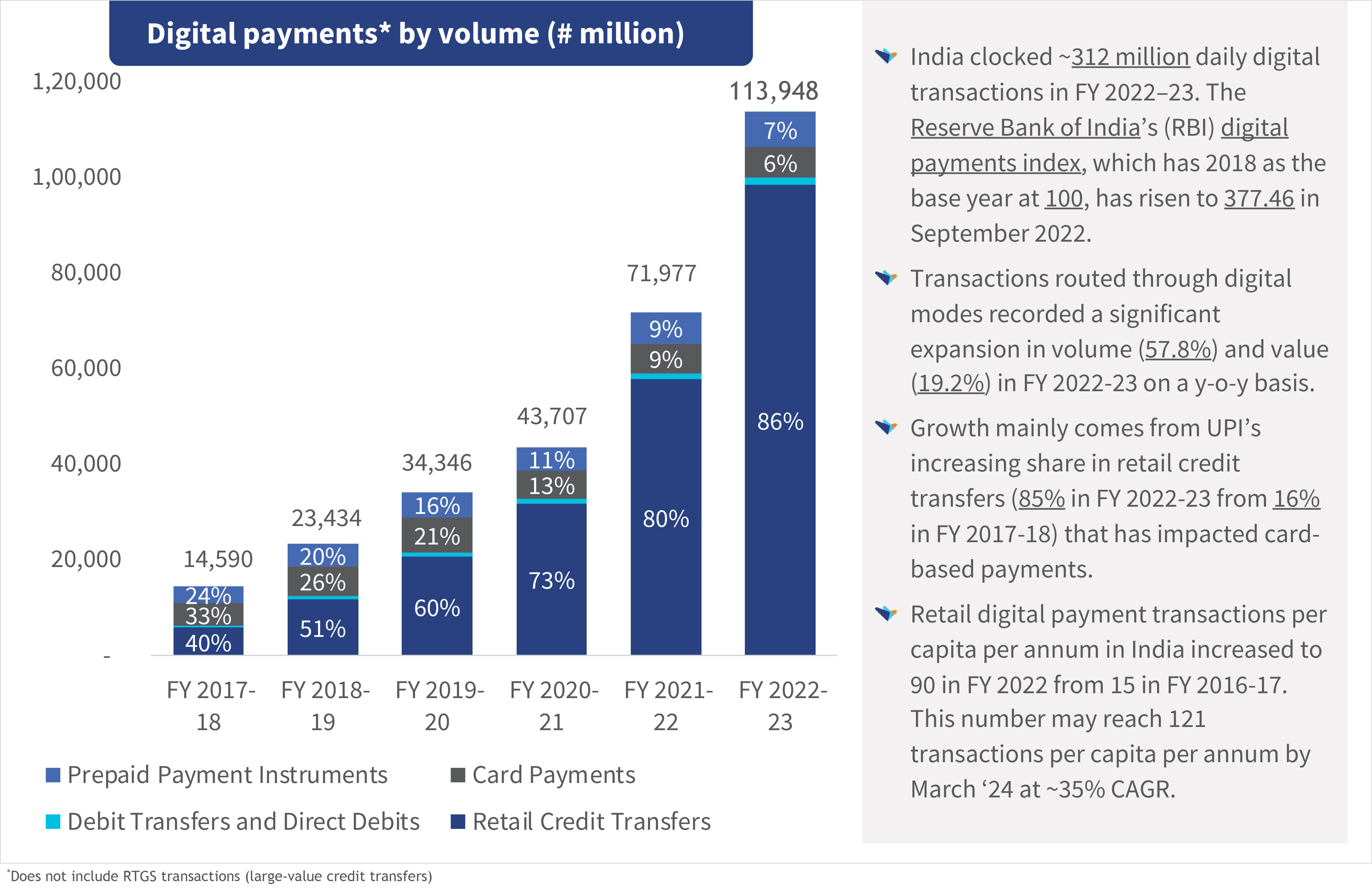

These conversations confirmed my belief that India would lead the digital revolution in our sector. Eko was, and indeed still is, a real trailblazer, and MSC is privileged to have worked with this remarkable organization from its inception to the present day. This can be seen in the growth of digital payments, which are poised for further proliferation.

The graph above shows that most of this growth has come from the Unified Payments Interface (UPI). Using UPI requires a smartphone and thus excludes many low- and moderate-income people. MSC has been working with NPCI on USSD- and IVR-based payments for feature phones, which can potentially unlock further significant growth in digital payments.

As India’s policy and regulatory landscape evolved at a blistering pace to drive digital financial inclusion, MSC pivoted, with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s support, to help:

- Business correspondent network managers navigate the ever-changing RBI directives and the correspondent banks’ demands and commission structures;

- Telcos develop and improve UX/UI for low-income people;

- Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) increases the speed of Aadhaar enrollments;

- Assess and accelerate the scaling of “no-frills” and PMJDY accounts for the Ministry of Finance;

- The uptake and rollout of the Ujjwala program to provide liquid petroleum gas (LPG) stoves to poor households to protect women’s health and free up their time;

- Startups develop technologies for low- and moderate-income people through the Financial Inclusion Lab at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad;

- Support to the National Payments Corporation of India to broaden and deepen the reach of digital payments;

- A broad range of government ministries design and deliver direct benefit transfer programs;

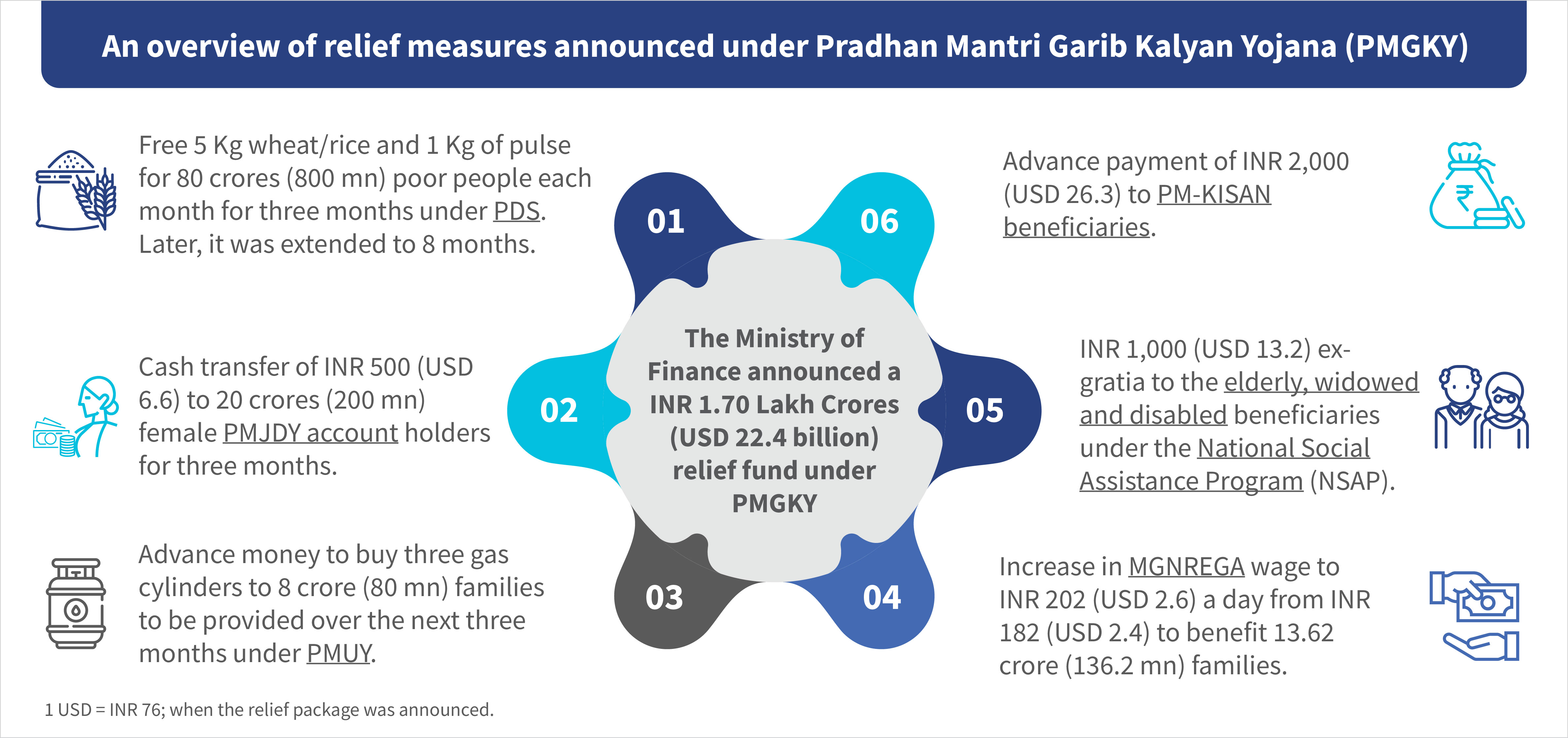

- In-depth monitoring and assessment of the national and state governments’ PMGKY response to the COVID-19 epidemic, in which we provided a dashboard for use by the Home Ministry and the Prime Minister’s Office; and, most recently;

The design and rollout of programs to support agriculture through policy advisory, support to farmer producer organizations, and most recently, the AgriStack and the ambitious Digital Farmer Services project.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the power of the payment rails built as part of the “JAM Trinity.” For example, millions of women could receive four payments of INR 500 from the government a few weeks after the pandemic started. This was extraordinary: a tribute to a government and civil service that genuinely cares about the low-income masses—and a public and private sector banking and technology industry that provides the services they need.

The digital revolution also allowed us to address the old elephant in the room: “Financial inclusion for what?” Now, MSC finds itself deeply involved in digital technology for effective government and regulation, social payments, enterprises, agriculture, education & skills, health & nutrition, WASH, and climate change. Today, we use technology for good and work alongside exciting public and private sector initiatives with the greatest minds in the country. As a videshi, I cannot express what a privilege it is to learn from and with some of India’s sharpest thinkers.

Twenty-five years ago, many observers saw India as a laggard in financial inclusion. Today, the India Stack has emerged as a cutting-edge model, an ecosystem that is unparalleled in the developing world, and a north star for others to follow—subject, of course, to modifications for their own markets and sociopolitical realities.

Today, in modern India, I can withdraw Rupees in cash or call home, all with a few keystrokes on my mobile phone. Yet poor people, particularly women, in the villages of Bharat and the slums of large cities remain largely marginalized, stranded on the wrong side of the digital divide and, increasingly, the climate crisis. As we look toward the next 25 years, we still have much work to do for equity and equality.

Written by

by

by  Jan 31, 2024

Jan 31, 2024 6 min

6 min

Leave comments