Impact of COVID-19 on farmers in Kenya and the government’s response

by Anup Singh, Diana Siddiqui and Aparna Shukla

Jan 19, 2021

7 min

This blog captures the analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on farmers in Kenya and their coping mechanisms. The blog further explores how the government is supporting the sector with relief measures, and what more needs to be done by the public and private agencies to help the sector recover.

The agriculture sector, the largest employer in the world, has been devastated by COVID-19. The measures taken by countries to curb the spread of COVID-19 have disrupted both demand and supply of agricultural products globally, particularly in developing countries where agriculture is labor-intensive. Although most countries designate agriculture as an essential service and exempt it from the restrictions in movement, the shift in demand from commercial to households coupled with the limited availability of logistical services has hit the sector hard.

Women are the backbone of agriculture and play a vital role in the local retail market, particularly in Africa. The outbreak of the pandemic further restricted their mobility, which was already low. They had to struggle to sell their produce and procure agricultural inputs.

As a result of COVID-19, farmers in Kenya now face several concerns and challenges. MSC carried out a dipstick study to understand the level of constraints the sector faces, how the government has been supporting the sector with relief measures, and what more needs to be done to help the sector recover.

Reduced income and the rising cost of cultivation has made farmers in Kenya more vulnerable

Agriculture dominates the economy of Kenya and employs more than 70% of the workforce. Agriculture contributes USD 1.37 billion in annual exports . The global lockdown has hurt Kenyan agriculture exports due to restrictions on the movement of goods. A study done by COLECAP indicates that Kenya’s agricultural industry suffers a loss of roughly USD 3 million every day during COVID-19 lockdowns.

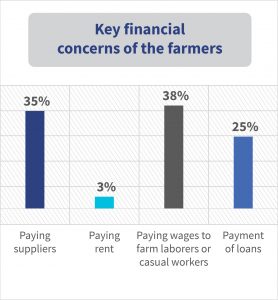

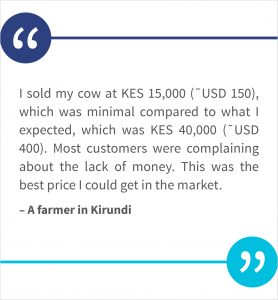

The pandemic led to a significant decline in household income. The unavailability of agricultural input materials and uncertainty about the marketing of the products has reduced production. Farmers who produce perishable goods like horticulture and floriculture outputs could not sell their products and incurred losses. At least 45% of farmers have seen their household income fall.[1] Other sources of income like poultry and livestock could not help them much due to a substantial drop in demand

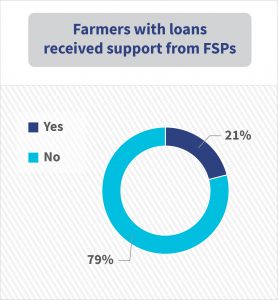

The burden of loan repayment and reduced options to borrow have further complicated the challenges in liquidity that farmers face. Among the farmers in the survey, 47% had accessed loans after the pandemic while others were unable to access loans due to rigorous rules and conditions, particularly around collateral. They had to opt for credit from informal sources.

Farmers have used the combination of coping mechanisms during the pandemic

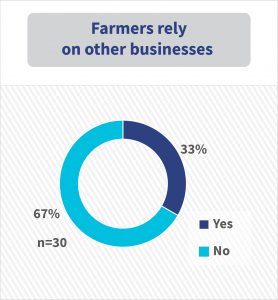

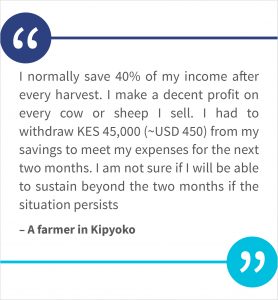

Among the farmers surveyed, 60% relied on savings during the pandemic to meet their household expenses. Many farmers are worried as they exhausted most of the savings during this period and urgently need access to alternative solutions. Farmers usually save in the form of productive assets and sell them when they need money. They did the same during the pandemic, but could not get the right price due to low demand as even the buyers now have lower purchasing power—see “Recovery and survival of micro and small enterprises in Kenya in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic”.

Digital credit provided some relief to many farmers helping them smoothen consumption. Farmers have also continued to rely on family and social networks to provide support to manage household expenses.

The government of Kenya has extended its support to the farmers

In May 2020, the Government of Kenya has announced a stimulus package of USD 503 million to support the sectors hit by the coronavirus pandemic. It covered eight areas including agriculture.[1] Of the USD 503 million, the government channeled USD 30 million for the supply of farm inputs to cushion 200,000 small-scale farmers in 12 counties across the country in the first phase.

At the time of reporting, the e-voucher program is being implemented in partnership with Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB) and Safaricom. The objective of the program is to reduce pilferage and promote the purchase of farm inputs by farmers. Small scale farmers with five acres of land or less are eligible for support in the form of an e-voucher worth USD 200 per acre. The government also allocated USD 15 million to assist horticultural and flower producers to continue accessing international markets.

The Ministry of Agriculture laid out protocols and guidelines at the onset of the pandemic to minimize interruptions within the food supply chain. These include:

- Designation of alternative market spaces for food vendors and farmers, such as stadia.

- Daily monitoring of prices of key commodities and food in major markets.

- Enforcement of recommended sanitary measures in market places, such as cleaning and sanitizing of markets after operations.

- Encouraging the use of digital technologies for food procurement and home delivery to minimize interactions.

Farmers need additional support to restore agricultural activities and reduce vulnerabilities

Increase the outreach of government programs

- Many farmers do not know how to access the e-voucher support program. The program’s coverage of 200,000 farmers in the first phase is widely seen as being insufficient. Private and public agencies can use digital channels, including mobile networks, to generate awareness of government initiatives for farmers to explain the eligibility criteria, entitlements, and the application process to avail the benefits.

In India, for instance, the technology platform Haqdarshak has built a repository of welfare programs and matches citizen profiles with welfare program eligibility. This enables prospective applicants to receive a customized list of eligible schemes. Haqdarshak works with the government, NGOs, and village-level entrepreneurs and has channeled benefits worth INR 1 billion (USD 13.67 million) to 296,100 beneficiaries. In Kenya, digital learning platforms, such as Arifu have used interactive SMS to provide training on good agricultural practices and financial literacy. Such platforms can be used to raise awareness among farmers on agriculture schemes. Further, radio and other electronic media campaigns should be tapped for effective coverage. Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture and Kilimo Media International (KIMI), for example, have used radio to provide agricultural extension services for smallholder farmers.

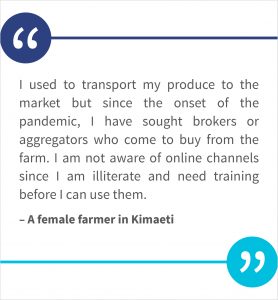

Access to the market for agricultural products

- The increase in transportation costs has made market accessibility more challenging for farmers. The government may establish collection centers for farmers to transport and sell their produce. It will also enable the government to store supplies for future use, enhance food security, and reduce market manipulation and the resultant fluctuations in commodity prices.

- Furthermore, the government can facilitate public-private partnerships to improve market linkages. Makueni County has invested in a mango processing facility, which has helped farmers to earn better income through value-addition and reduction in post-harvest loses.

Agricultural finance

- Farmers need immediate credit to meet sowing and cultivation expenses as they have used up their savings for household expenses. The availability of collateral-free, emergency finance can help them manage their situation in light of COVID-19.

The government and private agencies can support financial institutions with loan guarantee funds. In 2008, IFAD and AGRA provided USD 5 million as a 10% first loss guarantee to Equity Bank to disburse USD 50 million in agricultural loans to farmers with little or no collateral[1]. Equity Bank developed “Kilimo Biashara,” an agricultural financing product designed to make funding available and affordable to small-scale farmers. Similar initiatives are required to help farmers in accessing credit during the pandemic. Moreover, donors or the government or both can extend support to financial service providers to design farmer-friendly financial products and services.

The crisis brought about by the pandemic has highlighted the persistent issues that ail the agriculture sector of Kenya and forced government and non-government organizations to develop systems and institutions to better prepare farmers to respond to adverse situations like COVID-19. Even during the crisis, some success stories have emerged that demonstrate the resilience of local agriculture and food systems that could be replicated by the government and private agencies in other parts of the country.

One such example is the Utoma Youth Group of Makori and Homa Bay counties. The group’s agri-business suffered due to the inter-county travel restrictions. However, the members soon shifted their focus to local markets. The members harvested the crops in morning and afternoon shifts and individually delivered the produce to the households complying with the safety measures of maintaining social distance and using personal protective kits. Youth who lost their jobs and returned to the village also volunteered to work in the fields and sell the grains and vegetables locally along with other group members. While the group still faces a financial crunch because of the lower prices that they can realize in the local market compared to the market in Nairobi, it has managed to keep business afloat.

These measures could harness the natural entrepreneurial resilience of Kenyan farmers, and enable them to bounce back from the setbacks and hardships arising from the pandemic. Indeed, the crisis could be an important catalyst for the reform and restructuring of agricultural and agri-finance markets in Kenya.

[1] Working paper: Credit guarantee schemes for agricultural development, The World Bank and Agriculture Finance Support Facility

[1] BORGEN Magazine

[2] The sample size is, clearly, too small to be representative and therefore the percentages throughout this blog should be seen as

indicative.

[3] Government of Kenya; Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperative; others

[4] Working paper: Credit guarantee schemes for agricultural development, The World Bank and Agriculture Finance Support

Facility

by

by  Jan 19, 2021

Jan 19, 2021 7 min

7 min

Leave comments