How policy changes could revolutionize how entrepreneurs in Kenya can access finance

by Doreen Njau, Kim Kariuki, Albert Bundi and Nicholas Mungai

by Doreen Njau, Kim Kariuki, Albert Bundi and Nicholas Mungai Apr 4, 2023

Apr 4, 2023 6 min

6 min

This blog examines the Kenyan government’s policy reforms that allow entrepreneurs better access to affordable and convenient credit. It specifically looks at how the government’s financial inclusion fund—the Hustler Fund—promises to improve the financial health of MSMEs.

Salon owner Stella was visibly excited after hearing the Kenyan President’s inauguration address. Soon after, she picked up her phone, dialed *254#, followed the message prompts, and waited. After 48 hours, she received a notification that she had qualified for a KES 8,000 (USD 62) loan from the Financial Inclusion Fund, known commonly as the Hustler Fund. Moreover, if she pays back the loan in seven days, she would have to pay no interest.

The Hustler Fund promises to improve the financial health of Kenyan MSMEs

The Hustler Fund receives support from KCB and Family Bank and is a first for the country. It targets individuals and micro and small enterprises that struggle to access formal financial services due to the documentation requirements and steep loan prices. The fund provides these individuals and enterprises greater access to convenient and affordable credit. Besides enabling access to loans at single-digit interest rates for people like Stella, the fund allows borrowers to save for short- and long-term goals.

Before the fund’s launch, Stella would take digital credit from formal financial service providers. She accessed loans of up to KES 5,000 (USD 39) to purchase stock for her salon business. As her business prospered, her credit line increased, as did her confidence. She borrowed to meet her family’s needs, hoping she would make enough from the business to repay the loan. Most times, she did.

Then in December 2018, her mother fell ill and had to be hospitalized. As the eldest in the family, Stella had no option but to exhaust her savings and borrow from family and friends to settle the hospital bill. In the same month, her business struggled. As Stella dedicated her time to caregiving, she left the business to her employees, who stole from her. A few even opened salons of their own and snapped up her customers.

After six months of struggle, Stella finally recovered her business, even though she could not repay all her loans on time. Unfortunately, her financial health plummeted by this time as her digital financial service provider had negatively listed her due to her unpaid loans. She could no longer access credit from formal sources. Once again, Stella was forced to seek out informal financial service providers to survive.

Due to her mother’s illness, Stella had already exhausted her immediate sources, including friends, family, and her savings group. Left with no choice, she turned to a moneylender who offered her a KES 100,000 loan (USD 770) at an usurious 30% interest rate to be repaid within two weeks. Unsurprisingly, Stella could not repay her loan, and her assets went up for auction.

Stella’s story is not unique. Sadly, more than 6 million Kenyans, or 19% of the country’s adult population, have been negatively listed since September 2022. This figure represents 32% of the 19 million listed on the credit reference bureaus countrywide.

The core elements of financial health include how well a household manages daily obligations, copes with risks, recovers from economic shocks, and grows by building or maintaining reserves. Yet more than half the borrowers defaulted on mobile loans in 2021. This was likely because borrowers often de-prioritize payment of mobile loans as these are unsecured and do not involve a risk of losing collateral. As a result of these and other factors, financial health in Kenya is declining, as per a household survey conducted by the Central Bank of Kenya, Financial Sector Deepening Kenya, and the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

Beyond the Hustler Fund, additional changes in the delivery of credit are shaping the country’s financial landscape.

In this situation, the Kenyan government has gone beyond the Hustler Fund to increase access to credit. It abolished negative listing and introduced a graduated system in which defaulters get a low score but remain eligible for credit from formal financial institutions. Lenders who decline credit due to an adverse CRB listing risk incurring a KES 2 million (USD 15,385) fine.

The new system allows lenders to price loans based on the borrower’s risk profiles. Bad borrowers can improve their scores through timely loan repayment, while good borrowers are rewarded with higher scores and better loan terms. The regulator has approved six banks to offer risk-based loans and is rolling this out in a phased manner.

The Central Bank of Kenya received applications for risk-based lending from more than half of Kenya’s Banks. A few have started to implement risk-based lending, albeit gradually. This has led to the removal of the interest rate cap, which earlier constrained providers’ ability to offer credit to higher-risk clients. Providers now charge as much as 16% per annum for business loans.

The developments in Kenya’s credit system are welcome. Hopefully, lenders and borrowers can collaborate to manage credit effectively. This collaboration is important given the challenging economic environment that has seen loan defaults exceed KES 514 trillion (USD 4 billion) for the first time in the country’s history. Otherwise, the government and regulator may be forced to step in and manage credit effectively —and indeed, they are willing to step in.

In 2019, MSC recommended against the negative listing of borrowers with small outstanding loan amounts. In 2020 the Central Bank of Kenya ordered digital lenders to stop listing defaulters who owed less than KES 1,000 (USD 8), who were the majority at the time. The same year, the Central Bank of Kenya acted to suspend the listing of borrowers in arrears of less than KES 5 million (USD 38,000) onto credit reference bureaus to allow these borrowers access to credit during the COVID-19 pandemic. While suspending the listing of borrowers could reduce the appetite for providers to extend credit, it had positive short-term effects of increasing liquidity for individuals and MSMEs during the pandemic.

Credit repair is a welcome development to increasing access to finance for MSMEs

In November 2022, the Central Bank of Kenya announced measures to remove blacklisted borrowers from the credit reference buraus list, that would cost KES 30 billion (USD 231 million). While this is less than 1% of the total banking sector loan portfolio, the action affected about 20% of the 6 million negatively listed borrowers. These measures only covered a discount of at least 50% of the non-performing mobile phone digital loans outstanding as of the end of October 2022, leaving more than 2 million borrowers still negatively listed on the credit reference bureau.

Despite the government and regulators’ efforts to repair credit, risk-adjusted interest rates offered by banks remain unaffordable for microentrepreneurs. As a result, they rely on cheaper sources of credit, such as savings groups, savings and credit cooperative societies, and the Hustler Fund.

Formal financial service providers have started to respond to this gap by providing digital tools to integrate savings groups. This is because the opportunity to mobilize funds cheaply attracts the providers to cultivate a pipeline of future borrowers. A few have also indicated an interest in extending more extensive credit lines to borrowers who repay their facilities with the Hustler Fund.

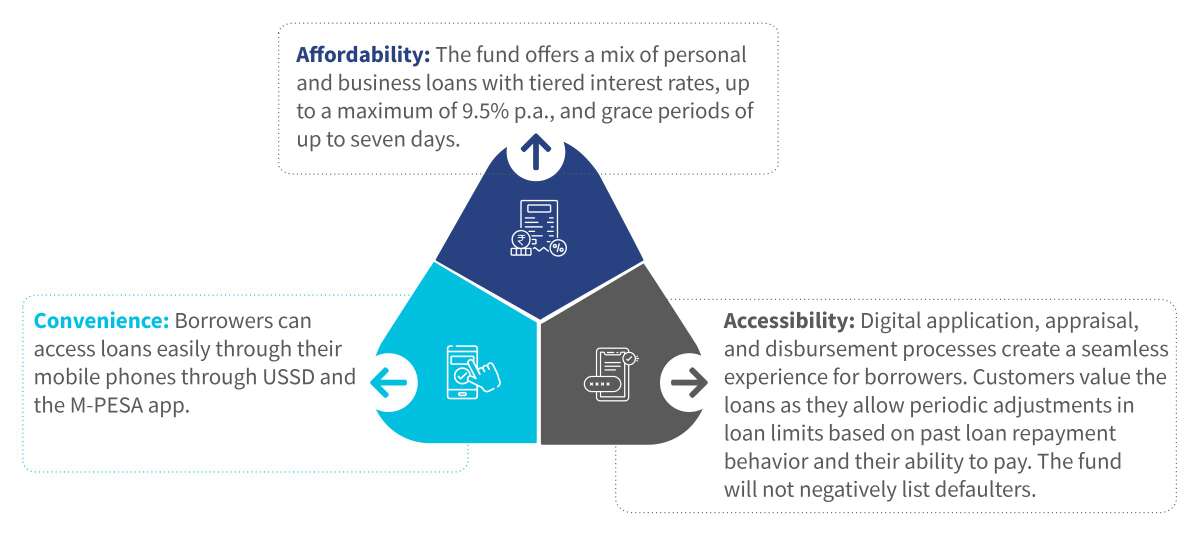

A closer look at the Hustler Fund reveals several appealing features for Stella and microentrepreneurs like her:

Unsurprisingly, 84% of the 19 million registered have borrowed from the fund.

Beyond credit, the fund automates savings, simplifying borrowers’ decision-making process, and serves multiple purposes. Firstly, the short-term saving component serves as collateral in case of default. Secondly, the long-term saving component contributes toward a pension. This is critical for mobilizing funds for economic development. Kenya’s savings as a percentage of the GDP is a paltry 16%, which is lower than emerging economies like Zambia at 43% or advanced economies like Qatar at 51%.

MSC has followed the fund’s rollout and identified three high-priority areas that need to be addressed by the ecosystem players to support the government’s ambitions of increasing access to credit for underserved persons:

- Linkages to financial sector actors need strengthening to avoid market distortions while increasing loan limits and minimizing over indebtedness. For example, data sharing will enable state and non-state actors to avoid saddling borrowers with excessive debt.

- Behavioral principles and data analytics should be used to encourage loan repayments through personalized messages and target at-risk customers based on predictive analytics, as with M-KOPA. Providers could also consider waiving a proportion of the risk-premium interest for borrowers if they repay their loans on time to encourage loan repayments.

- Monitoring and evaluating the fund from the perspective of state and non-state actors should be done to create a comprehensive feedback loop to optimize fund use and effectiveness. For example, data analytics can help the government and financial institutions improve fund performance and increase customer centricity.

Leave comments