How much has changed in just 20 years – Part 1

by Graham Wright

Apr 5, 2019

5 min

Twenty years ago, MicroSave was set up to try to support the development of savings and other non-credit services for low-income households.

In 1998, microcredit organizations, optimistically called microfinance institutions or MFIs, dominated the market. They offered standardized working capital loan products, repayable in weekly instalments. Any savings options were typically limited to “compulsory savings” that were locked in until the client, often referred to as “the member”, left the organization. Unsurprisingly, many clients left just to liquidate their compulsory savings balances.

So what has changed?

- From microcredit to microfinance to financial inclusion to financial health

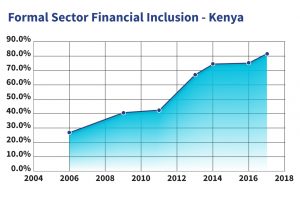

Over the past two decades, we have seen a change in the terms that are used to describe the industry and its objectives.Cynics would argue that this reflects the body of research that highlights that microcredit has little impact on the income of participating households. However, the evolution of these terms is both important and positive. While there was too much conflation of microcredit and microfinance, the latter term was important. As a term, “microcredit” reflects a recognition that low-income households need access to a range of financial services and not just mono-product working capital credit. The use of financial inclusion as an objective recognized that low-income households should be able to participate in formal financial systems instead of being stranded in the higher risk informal sector.

It is, however, the recent move to assess the success of the industry based on clients’ “financial health” that is most important. The shift reflects the importance of the outcomes rather than the output. These outcomes include savings that are set aside and available for the household to use to respond to emergencies or opportunities. The outputs in this context are the ownership of a savings account or a mobile money wallet—whether dormant or not.

A recent Gallup study for MetLife Foundation concluded, “The relationship between account ownership and perceived financial control is weak at best.” Access to a bank account is not useful by itself, particularly if the customer does not fully trust either the formal, or the digital financial system, or distrusts both. We need to design and deliver financial services that poor people want and can use to manage their money better. We will need to use fintech front-ends to offer these in a way that both corresponds to and aligns with their mental models.

Moreover, we need these financial services to integrate with the real economy and facilitate participation in it, so that people are not just financially—but also socially and economically included. The digital revolution provides the opportunity to do this.

2. From analog to digital

In 2005, after recognizing the potential of digital financial services in the seminal Electronic Banking for the Poor – Panacea, Potential and Pitfalls, MicroSave was working with Safaricom, Commercial Bank of Africa, and Consult Hyperion on M-PESA. Although GCash and SMART had started earlier, this was the beginning of the digital revolution—and the move from analog to digital. It is difficult to overstate the importance of this move and its profound implications.

Not only did the move offer a completely new range of opportunities to reduce the costs of delivering financial services to the mass market, but it also promised a new era of access for low-income households. The move to digital opened up new business models that required volume and scale if they were to achieve profitability. Furthermore, these business models require deep pockets to finance the infrastructure required to deliver the services. As a result, a range of new players, specifically mobile network operators (MNOs) and big banks began to deliver the services—as far as regulation and their boards would allow them.

Unsurprisingly, MNOs led the charge. Only recently have we seen a significant number of banks begin to respond and recognize the potential of the digital revolution to serve the mass market. Unless they serve niche and remote markets, traditional MFIs are essentially left with a choice to “adapt or die”. Some, but not all, are now reacting accordingly.

This massive change in the market not only affected financial institutions, but it also transformed the nature of the consulting market in which MicroSave operated. Small and medium consulting companies like MicroSave were used to competing with peers. We served and supported the growth and refinement of the strategy and operations for MFIs. With the arrival of MNOs and large banks, we found ourselves with an entirely new set of competitors. We were going head to head with the consultants that had served these large corporations for years—the big 4 accounting firms, along with McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group, and Bain.

3. Digital services and the real-world economy

The move to digital has allowed us to start to answer the all-too-often unasked question— “financial inclusion for what?” with much more credibility. Until only a few years ago, it was assumed that providing people access to formal financial services was valuable by itself—that they would use these services to manage their household budgets more effectively and reduce the risk inherent in informal approaches to storing and managing money. The good news is that people now question that assumption and look for ways to design tools, services, and even apps that help low-income houses meet their needs in the real-world economy. So, how can they finance farm inputs, education expenses, housing, old age, emergencies, among other expenses?

This is not new, but has become a lot more explicit and baked into the design of projects to support financial service providers. However, the digital revolution allows us to take this one stage further to support and finance people’s activities in the real world economy. As a result, there is a growing array of approaches to digitizing agricultural value chains, which include a range of inputs as well as post-harvest marketing with “precision farming”, as well as extension or advice. There are also efforts not just to digitize schools fees but the education process itself. Similarly, digitizing healthcare and remote advisory systems are becoming increasingly advanced.

While many of these are still either small in scale or are controversial, or both, they represent tremendously exciting advances in approaches to complement plain vanilla financial services and to build services that add real value to efforts to reduce poverty and vulnerability.

All that said, in our love affair with all things digital we risk losing sight of the rapidly emerging digital divide. As we roll out a range of empowering and engaging tech solutions for those with access to 3G+ coverage and smartphones, we could leave women and remote, poorer communities even further behind than they already are. This issue requires both better articulation and deeper thought. It appears that the digital divide is being wilfully ignored amid the excitement of the potential of the digital revolution to change lives for the better—for those able to access it.

In the next blog in this series, I will take a hard and critical look at the influences of Silicon Valley, the rise of foundations, and the evolution of the role of traditional multilateral and bilateral donor agencies.

Written by

by

by  Apr 5, 2019

Apr 5, 2019 5 min

5 min

Leave comments