Grievance redress mechanisms in welfare programs: A milestone yet to be achieved

by Jayan Nair and Mahima Dixit

Sep 28, 2022

5 min

This blog identifies the challenges in grievance resolution for Direct Benefit Transfer programs in India. It suggests ways to reform the existing Grievance Redress Mechanism (GRM) to ensure maximum inclusion of eligible beneficiaries in these programs.

“Calling on the toll-free numbers does not help, as most of the time, the numbers do not work or the call disconnects. Visiting government offices is the only way for us to register grievances.”

– A National Pension Scheme beneficiary in India

“We have to visit the offices several times without knowing the point of contact or where to raise our grievances. We often return without getting any resolution, losing a day’s wage.”

– A PM-KISAN beneficiary from the state of Madhya Pradesh

Many Indian citizens receive social security from government-backed schemes—a term used in India for large-scale programs. The Government of India relies heavily on Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) schemes to deliver the scheme benefits to people who need them most. Yet many beneficiaries across India’s far-flung corners face a barrage of challenges linked to unresolved grievances, which lead to their exclusion from the schemes altogether.

Why do beneficiaries of welfare schemes struggle with grievance resolution?

Like many government bodies, the Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances established a process to resolve grievances at the central level. These methods to manage grievances are known as Grievance Redress Mechanisms (GRM) in South Asia. Yet its effective implementation falls short. MSC’s evaluation of many DBT schemes suggests that existing systems to resolve grievances are not robust enough to respond to the many challenges faced by beneficiaries.

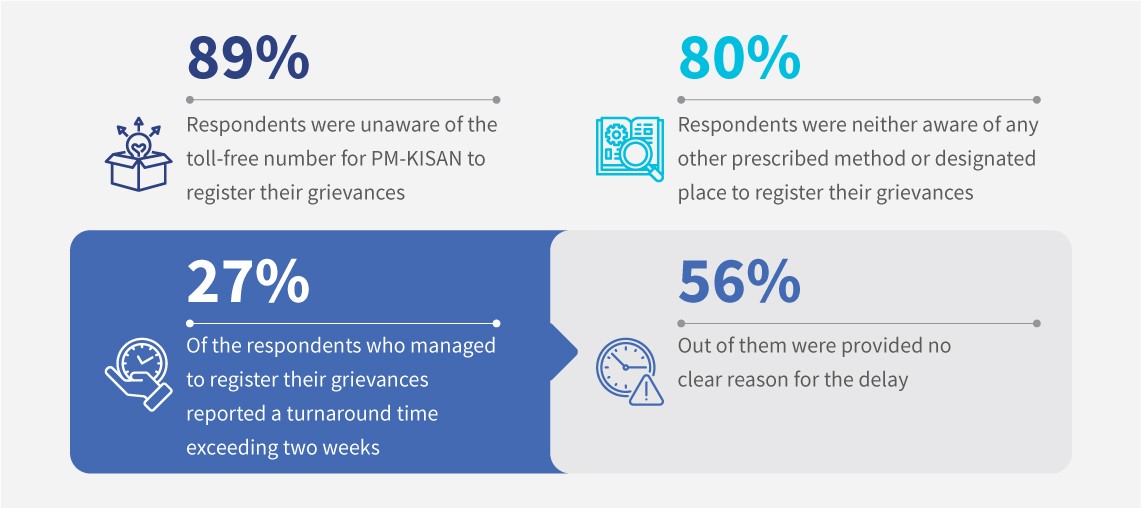

Source: MSC’s evaluation study of PM-KISAN

This blog compiles data on the state of GRM from the study of DBT schemes alongside observations from corresponding field visits. We document challenges with the GRM systems and suggest ways to transform them into more beneficiary-centric mechanisms.

4-A: The pain points:

The “4-A pain points” framework elaborates on the major challenges the beneficiaries face to get their issues resolved:

Many beneficiaries remain in the dark regarding grievance registration and resolution. They are not informed of the dedicated portals, toll-free helpline numbers, or other channels of grievance resolution launched by the government. An assessment of DBT in Education in Uttar Pradesh, India, reports that 83% of respondents who did not complain about failure to receive benefits did not know of the concerned channel to resolve their grievances.

Accessibility:

For many DBT schemes, the government helpline numbers are inactive. The beneficiaries lose wages as they travel long distances and search frantically for the relevant authorities at the block (sub-district) or district offices. Many beneficiaries choose to forgo registering their grievance due to these accessibility issues. “The district office is more than 15 km away from my village. It becomes difficult to travel such long distances and register a complaint at the cost of my work,” says Murali, a farmer from Rajasthan, who missed his last two installments of the PM-KISAN scheme.

Availability:

Dedicated, beneficiary-centric GRM units to address the beneficiaries’ grievances are absent. “We lack designated offices close to our village that could solve our issues. We are told to visit the block office, but we are unaware of the point of contact,” notes a PM-KISAN beneficiary farmer from Chhattisgarh. When the beneficiaries approach the concerned officials, their issues remain unsolved. The officials are frequently swamped with other administrative priorities and fail to solve their problems or even provide guidance.

Accountability:

The current GRM for welfare schemes does not place accountability on the supply-side stakeholders. Most GRM systems used in DBT schemes lack a standardized operating procedure (SOP) to resolve grievances. Although the system has in place essential components, such as a standard turnaround time (TAT), escalation matrix, and feedback mechanism—beneficiaries fail to use these to their advantage. For example, the PM-KISAN guidelines mention a TAT of two weeks for the registered complaints. But our study suggests that many beneficiaries had unresolved complaints for months, even after they approached concerned authorities. They did not know about the TAT and their rights to escalate the problem.

How to tackle these pain points?

The following recommendations would help build responsive and beneficiary-centric GRM systems:

1. Below-the-line advertising: An important tool to spread information

Currently, communication campaigns for the DBT schemes focus on mass marketing strategies, such as hoarding and banners at prominent locations and advertisements in the electronic media, rather than through awareness-building at the individual level. Below-the-line advertising strategies, such as customized pamphlets and SMS in the regional language, could help in better penetration of the information at the individual level and improve the rate of grievance registration. The SMS that beneficiaries receive on benefit transfer can also include additional information on channels to register grievances and guidance on using them

2. Setting up local grievance resolution centers for improved accessibility and availability

One step is to use the nationwide network of 373,877 Common Service Centers (CSCs) as GRM centers. Our study suggests CSCs are the critical point of contact where digitally illiterate beneficiaries extract information on the status of their application or reasons for non-receipt of scheme benefits. These centers can be equipped and empowered to make specific basic edits to beneficiary records. For example, they could be empowered to update the Aadhaar details, contact number, and errors in application forms. However, providing access to beneficiary data to CSCs must not happen at the cost of privacy, and the SOP needs to specify this clearly. The vast CSC network can save beneficiaries the effort and time of visiting a government office with grievances. The 140,000 India Post branches could also be used for this.

We can also draw inspiration from the Rajasthan Government’s flagship “Prashasan gaon ke sang” campaign, under which camps are set up to provide local access to government services and resolve grievances in the remotest villages of the state. These camps give people access to 22 government departments for immediate identification and resolution of issues related to government schemes and services. The “e-mitra” kiosks are also present to facilitate any immediate online formalities related to the schemes. These camps serve as a one-stop destination for citizens who face issues of inaccessibility, digital illiteracy, and lack of information on resolving grievances. Such mobile GRM units can be replicated across states to offer an accessible and approachable mechanism of grievance redress for the G2P DBT schemes.

3. Revamping the grievance management portals and setting up accountability mechanisms

An SOP should be prepared to outline the processes to resolve grievances for these schemes clearly. It should contain clear guidelines on TAT for grievance resolution, the escalation matrix, and a feedback mechanism. The introduction of an escalation matrix would speed up the resolution process and inculcate a sense of accountability among the officials. This would also help the state GRM cell monitor the complaints regularly, ensuring a seamless process flow. The feedback mechanism will help understand the beneficiary experience and gauge their satisfaction level.

A Complaint Management System (illustrated above) should be introduced to make grievance redress transparent. This system is similar to the process flow of the Central Public Grievance Redress and Monitoring System (CPGRAMS)

A “State GRM Ranking” could be prepared based on regular audit and monitoring results. Such an initiative would encourage a spirit of competition among the states and ensure effective grievance resolution at their level. The best-performing ones could be incentivized, and training and learning sessions can be structured for laggard states.

The Government of India has recently announced its commitment to target 100% coverage of welfare schemes. The recommendations in the blog are ambitious. Yet if implemented, they could significantly improve the GRM system for DBT schemes in the country and thus speed up the maximum inclusion of beneficiaries.

Written by

Jayan Nair

Assistant Manager

by

by  Sep 28, 2022

Sep 28, 2022 5 min

5 min

Leave comments