Responses to the financial impacts of COVID-19 through social cash transfers and digital payment infrastructure

by Caroline Pulver

May 14, 2020

7 min

The financial impact of COVID-19 has been hitting the poor. Governments are adjusting cash transfer programs and utilizing national payment systems to mitigate these negative impacts. This blog reviews responses from Latin America, Asia and Sub Saharan Africa where governments with limited resources are coming up with innovative solutions to the crisis.

Countries with well-developed digital payments infrastructure and shock-responsive social cash transfer systems have been able to respond rapidly to the negative impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. A faster response can lessen the financial impact on the poor. This means that beneficiaries do not have to resort to negative coping mechanisms, such as selling productive assets—such as livestock or tools—which may undermine their ability to earn a living and recover financially in the long term.

Using digital delivery mechanisms instead of delivering physical cash or food parcels is an advantage as it supports social distancing, thus reducing the risk of spreading the disease. These early responses to the economic impacts of COVID-19 also provide a guide for other national governments, demonstrating several measures to support a governmental response—both “quick-fixes” and long-term investments.

World Bank Group President David R. Malpass said that the challenges that stem from COVID-19 represent “an unprecedented crisis, with devastating health, economic, and social effects felt around the world.” He stated, “If we do not move quickly to strengthen systems and resilience, the development gains of recent years can easily be lost.” He added that while the pandemic’s effects are global, “this crisis will likely hit the poorest and most vulnerable countries – and people – the hardest.”

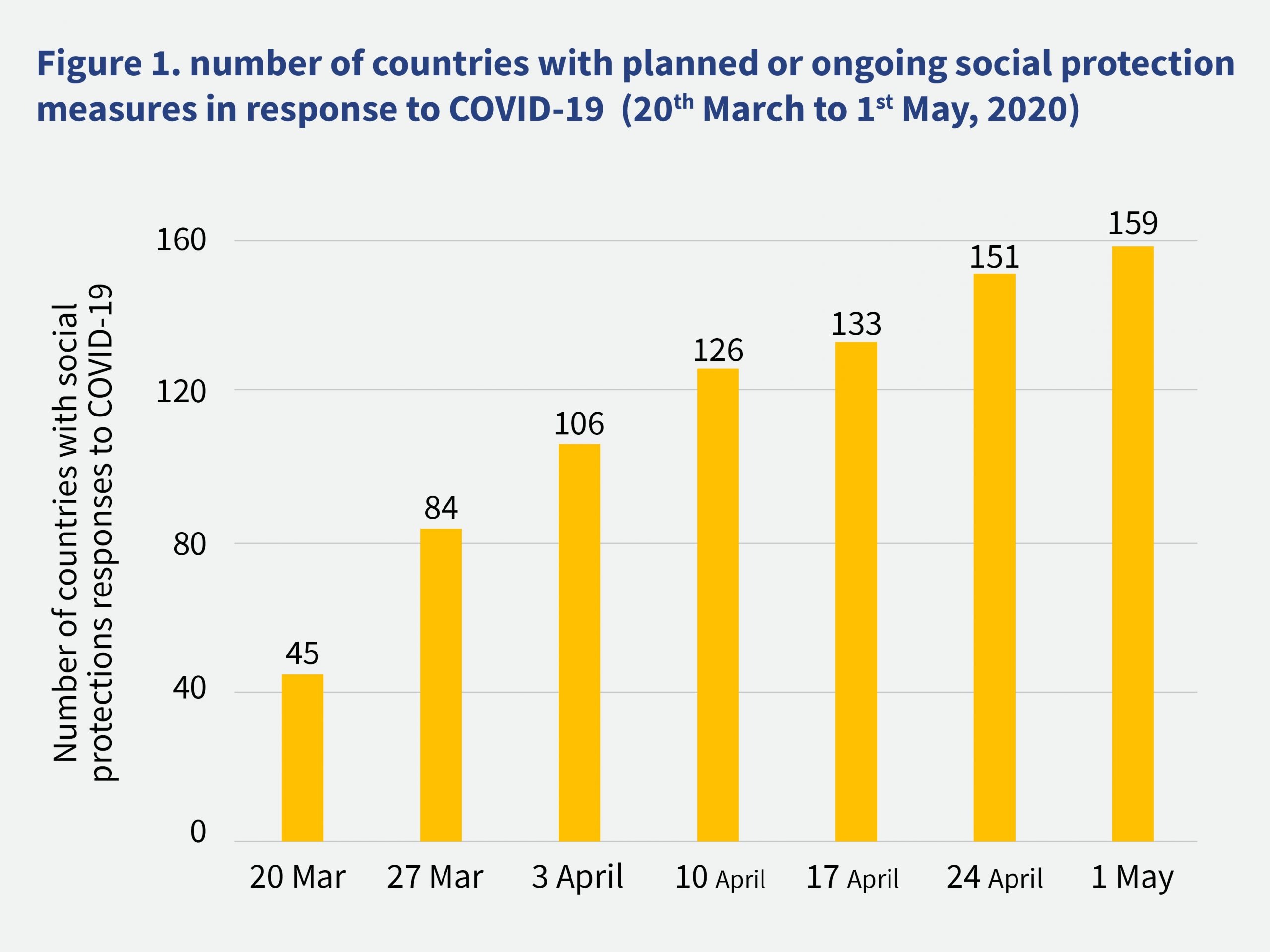

As of 1st May 2020, 159 countries have planned, introduced, or adapted 752 social protection and jobs measures in response to the pandemic. The increasing number of countries responding with social protection measures has been striking—growing from 45 countries as at 20th March to 151 countries by 24th April. Initial estimates of the investment going into social protection response to COVID-19 are at over half-trillion US dollars (USD 567 billion).

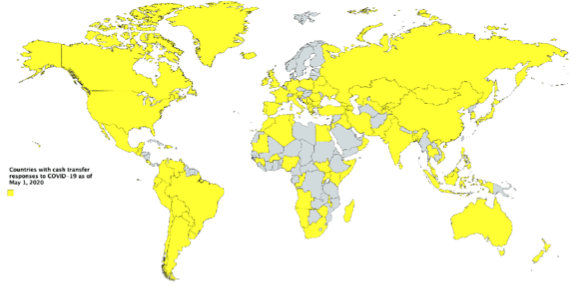

Among classes of interventions, social assistance or non-contributory transfers are the most widely used, accounting for 60% of the global response (455 measures), followed by actions in social insurance (27%), and supply-side labor market programs (13%). Within social assistance, cash transfer programs (54%) remain the most widely used intervention by governments.

Social protection measures graphic representation

This article reviews responses in three regions: (1) Latin America—where some of the first responses were initiated (2) Asia—home to some of the largest programs, and (3) Sub Saharan Africa—where governments with limited resources are coming up with innovative solutions to the crisis.

Across Latin America, several extensive and rapid responses have come up to mitigate the crisis. Many of these responses target informal workers and are built on existing payments infrastructure. In high-income Chile, the government made payments worth USD 15 under the “Bono COVID-19” initiative directly to the bank accounts of 2 million vulnerable people—predominately informal workers—in April. These payments were made possible by the national ID-linked basic bank account “Cuenta Rut”.

In upper-middle-income Colombia, the 2.6 million beneficiaries of the Familias en Acción program will each receive an extra payment worth USD 98. The government of Colombia has also launched a new cash transfer program, “solidarity income”, which provides a single payment of USD 108 each to at least 3 million informal workers and their families. The program ensures payments through bank accounts for the half of identified households who have them, and through electronic payments via mobile phones for others.

In upper-middle-income Peru, the government has been making a payment of USD 108 to each of the 2.7 million homes classified as poverty-stricken. Authorities in Peru have previously delivered G2P payments to accounts. However, under their COVID-19 response, they have increased the set of financial service providers to include private banks and mobile money providers to increase accessibility for beneficiaries.3

In Brazil, the government is adding 1 million households to its Bolsa Familia program. The Government of Brazil has also established a new three-month emergency cash transfer program of USD 115 each per month (or 60% of the minimum wage) for informal workers. The beneficiaries under the new program will be identified through Cadastro Unico, the country’s social registry.

Meanwhile, in middle-income Argentina, in April the government-approved payment of USD 151 each for informal workers, who make up 35% of the nation’s economy. In lower middle-income El Salvador, the government has announced a new cash transfer to support 1.5 million households in the informal economy with a USD 300 payment to each. The government targeted households with low electricity usage, such that any household with monthly consumption of 0-250 kilowatts per hour received the transfers.

In India, the government has sought to mitigate some of the negative impacts on poor households through a rapid response using existing programs. On 24th March, the government started its lockdown; 10 days later, through a new three-month cash transfer program, the government paid USD 6.50 into 204 million accounts of female beneficiaries of the existing financial inclusion program “PMJDY”.8 The government paid USD 13 each to 35 million beneficiaries under the National Social Assistance Program (NSAP) for the elderly, widows, and the disabled who receive social pensions.

In Indonesia, the flagship CCT program, PKH, will temporarily increase the benefit level by approximately 25% for three months and expand the program from 9.2 million to 10 million beneficiaries, or 15% of the population, starting in April. The authorities have brought payments forward and will disburse them monthly instead of quarterly.7

In Pakistan, the government launched its four-month “Ehsaas Emergency Cash Program” for 10 million families. The program will identify 3 million affected households through the national socio-economic database—while the eligibility threshold will be relaxed upwards. An SMS campaign will be launched to inform low-income families about the program.

Likewise, in Thailand, the government initially announced a new three-month cash transfer that pays USD 153 monthly to each of the 3 million workers who are not covered by the Social Security Fund. A week later, it increased the coverage to 9 million, although 21.7 million have applied for support. The total program cost is USD 4 billion.7 Thailand’s recent reforms allow payments to be sent to bank accounts through its fully interoperable PromptPay system. The country’s digital payments ecosystem also reduces the need to cash out. Additionally, Thailand has the advantage of a digital ID system that uniquely identifies recipients, which allows the government to determine eligibility and deposit directly to the account the beneficiary has linked to their ID.3

In Sub-Saharan Africa, underdeveloped payments infrastructure, national ID systems, and safety net systems have hampered responses. Yet the continent still provides interesting insights on how to target low-income families most affected by the crisis.

In Burkina Faso, the government announced a new USD 10 million cash transfer program for informal workers—fruit and vegetable sellers—with a special focus on women. In Ethiopia, the government expanded and adjusted its existing Urban Productive Safety Net Programme – beneficiaries will receive an advance payment for three months while on leave from their public works obligations.

Lower middle-income Kenya has a well-developed social safety net—the Inua Jamii program, which supports 1 million people, allocating them USD 19 per month each. The National Treasury appropriated an additional USD 100 million for the program in response to COVID-19. In Malawi, as part of the government’s National COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plan, the government has proposed measures to accelerate payment of Social Cash Transfer Program (SCTP) benefits in April. It would fast-track SCTP payments with a four-month payment that covers the period up to June. The Government is also proposing to provide top-ups to SCTP beneficiaries and to increase SCTP coverage in rural areas (as of June) and urban areas from April-June.

The South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) started providing early payments of social grants to older persons and persons with disabilities from 31st March, and grant amounts have been increased effective 1st April. On 31st March, the Government of Zimbabwe announced that USD 550,000 per month would be set aside for the next three months for an emergency cash transfer program to reach 1 million vulnerable households.

African countries have made efforts to encourage the use of digital payments to support social distancing and hence cut the risk of transmission. The Western Africa Central Bank (BCEAO) has taken several steps to promote the use of electronic payments. BCEAO is a central bank that serves eight west African countries—Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo. The steps include providing flexible measures to open a mobile money wallet and making transfers person-to-person electronic money transactions free.7

In Ghana, commencing all mobile money transfers of GHS 100 and below became free of charge from service providers from 20th March 2020 for the next three months. Kenya introduced fee waivers on person-to-person mobile money transactions on M-PESA on 17th March for three months for transactions under USD 10. This followed a directive from Kenya’s President, Uhuru Kenyatta, “to explore ways of deepening mobile-money usage to reduce the risk of spreading the virus through physical handling of cash”.

Governments have launched new initiatives and used existing social cash transfers to meet the needs of low-income families affected by the economic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. The changes to existing cash transfers have included increasing transfer values (Indonesia, South Africa, Ethiopia), providing additional one-off payments (Colombia, India), increasing the number of beneficiaries (Brazil), changing payment terms—making payments in advance, and increasing the frequency of payments (Ethiopia, Malawi, South Africa). Countries that have national ID linked to bank accounts, such as Chile, India, and Thailand, support rapid disbursement. Allowing a greater number of financial service providers to disburse payments may increase accessibility for beneficiaries and support social distancing (Peru).

The response to the COVID-19 crisis may accelerate the digitization of payments. There are some basic regulatory changes that central banks can make in support of the digital payment ecosystem. For example – allow non-bank e-money providers to provide cash-out services and fast-track, new entrants, by issuing licenses to mobile network operators, among others.

by

by  May 14, 2020

May 14, 2020 7 min

7 min

Leave comments