Fighting DFS fraud from five fronts

by Vera Bersudskaya

Nov 14, 2016

6 min

When it comes to fraud in digital financial services (DFS), stories from Uganda will surely arise: This blog proposes five avenues where DFS providers can step up the fight against fraud in DFS.

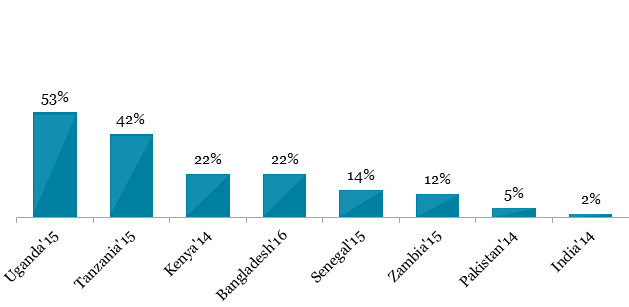

Figure 1. Agents reporting Fraud: ANA Research Countries

Source: ANA Uganda 2015, The Helix Institute of Digital Finance.

Five Ways to Tackle Fraud

- Conduct periodic mass education campaigns. These are critical for creating and sustaining awareness about fraud among customers and agents alike. Ugandan providers should continue to invest in above-the-line communication on the variety of fraud risks, ideally in partnership with Bank of Uganda and the media. As the guardian of consumer protection, the Bank of Uganda has taken successful initiatives to educate the public on how an agent is expected to operate. Its continued involvement in such efforts would bolster their credibility.

A good example is Safaricom’s campaigns. Safaricom used multiple channels – from SMS blasts, newspaper ads, to skits and radio spots in local dialects – for targeted communication about fraud. Furthermore, its ‘PIN Yako Siri Yako’ (Your PIN Your Secret) campaign has increased user awareness on keeping their PIN number secure.

- Revamp internal systems and processes to ensure adherence to clear protocols.

- Providers may need to clarify their operational protocols for fraud identification, management and reporting and relay this to all of their stakeholders—from agents and aggregators/master agents to sales and distribution managers, to ensure a shared understanding of the protocols.

Essential within these protocols are effective complaints and redressal mechanisms accessible 24/7 in local languages, with dedicated customer- and agent- hotlines. In Kenya, some providers accept customer complaints via social media, which given their open nature, can result in faster turn-around and keep other customers informed about the lastest fraudster tricks.

Regardless of the medium, these mechanisms should adhere to clear procedures for transaction repudiation, complaint escalation, and logging customer- and agent-reported fraud incidents. Aggregate statistics on fraud should be regularly transmitted to internal and external sensitisation channels to ensure that the latest information is integrated into consumer education as well as agent and internal staff training.

b. According to a study by Deloitte, the primary root causes of mobile money fraud are internal control failures related to governance, IT, and continuous monitoring. Providers should strive to implement preventative and detective safeguards. Some examples of these measures, among others, include:

- Disabling incoming SMS/calls from unauthorised numbers on transaction SIM cards;

- Allowing access to web terminals from secure terminals only;

- Requiring two-factor transaction authentication for web and corporate accounts;

- Enabling record-keeping through SMS confirmation; and

- Regularly monitoring high-value/high volume transactions.

c. Robust analytics are the backbone of fraud monitoring and management. However, Ugandan providers have not yet fully developed their capacity in this area. Data systems and analytics should include at a minimum: transaction pattern tracking with time/location stamps and reference numbers (with automatic blocks applied to customer and agent accounts flagged for suspicious activity), float and cash balance monitoring, as well as periodic commissions’ analysis to detect agent-perpetrated fraud.

One example is recent collaboration among leading Ugandan providers to claw back commissions for direct deposits by analysing transactions’ locations and time stamps. This was done using BTS/Booster detection – deposits withdrawn from the same account in a different location within several minutes were not remunerated.

d. Automation can significantly reduce opportunities for fraudulent meddling by agents and employees. Providers should prioritise automating transaction reconciliation (B2B, C2B), tariff collection, and aggregator/agent commission pay-outs. Enabling customer cancellations, modelled after M-PESA’s Hakikisha, could help curb customer-facing fraud. To further protect customers, systems could auto-generate SMS warnings to those using common PINs like 0000 or 1234.

- Improve staff and agent network management through enhanced training and monitoring, as well as stricter recruitment and contracting.

- Training. It’s encouraging that Ugandan providers are already training their agents and staff on fraud. Providers are formalising training curricula through Training-of-Trainer manuals. As these are compiled, they may want to ensure that manuals include a comprehensive fraud typology. This can include practical prevention tips such as:

- Complying with customer KYC;

- Keeping agent materials secure;

- Picking difficult to guess passwords;

- Identifying counterfeit currency identification;

- Adhering to customer privacy standards;

- Handling customer complaints; and

- Regularly updating the agents and staff on the latest types of fraud and prevention strategies.

b. Monitoring. Providers have already started using agent support and monitoring visits as an opportunity to address the issues of fraud and operational compliance. Such visits are a convenient, periodic opportunity to check the level of agent awareness and compliance to KYC procedure, inspect mandatory tariff disclosure, ensure password security, and check for counterfeit currency. They can also be used to inform agents of emerging fraud trends and best practices in fraud mitigation elicited through internal redress channels, feedback at conventions, or experience-sharing provider fora. Of course, staff conducting such visits must also carry proper identification, given cases where agents have been defrauded by fraudsters posing as provider support staff in the past.

Visits by a provider or third-party personnel could be supplemented with mystery shopping exercises by the regulator to check compliance. Providers may further consider enabling aggregators/master agents to access their agent transactions via a specialised portal. This could boost their ability to track sub-agent performance and identify unusual activity.

c. Agent Recruitment and Contracting. The Bank of Uganda’s Mobile Money Guidelines already dictates minimum agent KYC credentials. However, given the prevalence of fraud in the country, providers would greatly benefit from expanding these criteria and revisiting their due diligence process to include background checks. These revised criteria and due diligence should not be limited to agents alone but should be extended to all employees, including aggregators/master agents. For example, Safaricom requires agent applicants to submit a certificate of good conduct from the Criminal Investigations Department of the Kenya Police.

Additionally, employee, aggregator and agent contracts must be reviewed to explicitly state the obligation of adherence to operational standards – in particular, those pertaining to fraud (e.g. customer KYC, transaction logging, tariff display requirements) – as well as grounds for dismissal.

- Factor fraud into product design. This will become increasingly important as more complex bundled products, such as digital credit, savings, and insurance products are introduced.

Greater product sophistication, delivered via partnerships between different financial service providers, could increase the opportunities for committing fraud. It will be crucial that all business partners involved are trained in fraud mitigation and have compatible fraud mitigation systems.

Prior to the roll-out of these products, provisions for complaints and redressal mechanisms – including division of roles and responsibilities, as well as communication channels must be clarified with the relevant staff receiving corresponding, specialised training. For example, in Tanzania, Commercial Bank of Africa (CBA) and its MNO partner, Vodacom, have agreed that all complaints regarding CBA’s product, M-Pawa, will be handled by Vodacom call centre staff, who receive specialised training from the bank.

- Enhance regulatory enforcement and the prosecution of offenders. While this recommendation does not pertain only to DFS providers, ensuring compliance to KYC is a crucial preventative step to fraud. Only 2% of Ugandan customers show identification when conducting a transaction, even though 84% have the requisite ID. Combating non-compliance on this particular issue must be done in collaboration with the regulator and the National Identification and Registration Authority.

Closer collaboration with the Uganda Police Force will ensure timely investigation and prosecution of fraud perpetrators. Ugandan providers have called for a common database of blacklisted agent employees to track fraudster handlers. Such an endeavour could be spearheaded by the regulator in partnership with law enforcement and National Identification and Registration Authority. The State Bank of Pakistan’s online database, AgentChex, enables the regulator to track agent transactions and flag those implicated in the fraud. It would be essential that such information is shared among all DFS stakeholders.

Fraud is an ever-evolving phenomenon and concern in Uganda. We hope the analysis of ANA data and our qualitative research offers some practical advice as to where providers may enhance their efforts to combat fraud effectively. The Helix Institute is vigilantly watching this space and equips the DFS community with preventative and mitigation strategies to address fraud in its Risk and Fraud Management Training Course.

The Helix Institute of Digital Finance would like to thank FSD Uganda for funding and supporting the 2015 ANA research in Uganda.

Written by

by

by  Nov 14, 2016

Nov 14, 2016 6 min

6 min

Leave comments