Enabling and financing locally-led adaptation – the role of blended finance and digital technologies

by Graham Wright, Anant Jayant Natu, Partha Ghosh, Wendy Chamberlin and Aarjan Dixit

Jan 19, 2024

4 min

The global community only spends 30% of the $387 billion on climate adaptation annually, a mere 10% of the required amount. Locally-led adaptation is crucial, addressing climate change impacts and community experiences. Successful initiatives include vulnerability, innovation, decentralized governance, and devolved finance. The private sector can play a critical role in financing, while digital technologies like AI can facilitate local-led planning and governance functions.

The global community spends just USD 30 billion annually on climate adaptation. However, when you put this figure into perspective, it represents a mere 10% of the projected USD 387 billion required each year (UNEP, 2023). Furthermore, a limited proportion of this funding actually reaches developing countries and finances locally-led initiatives.

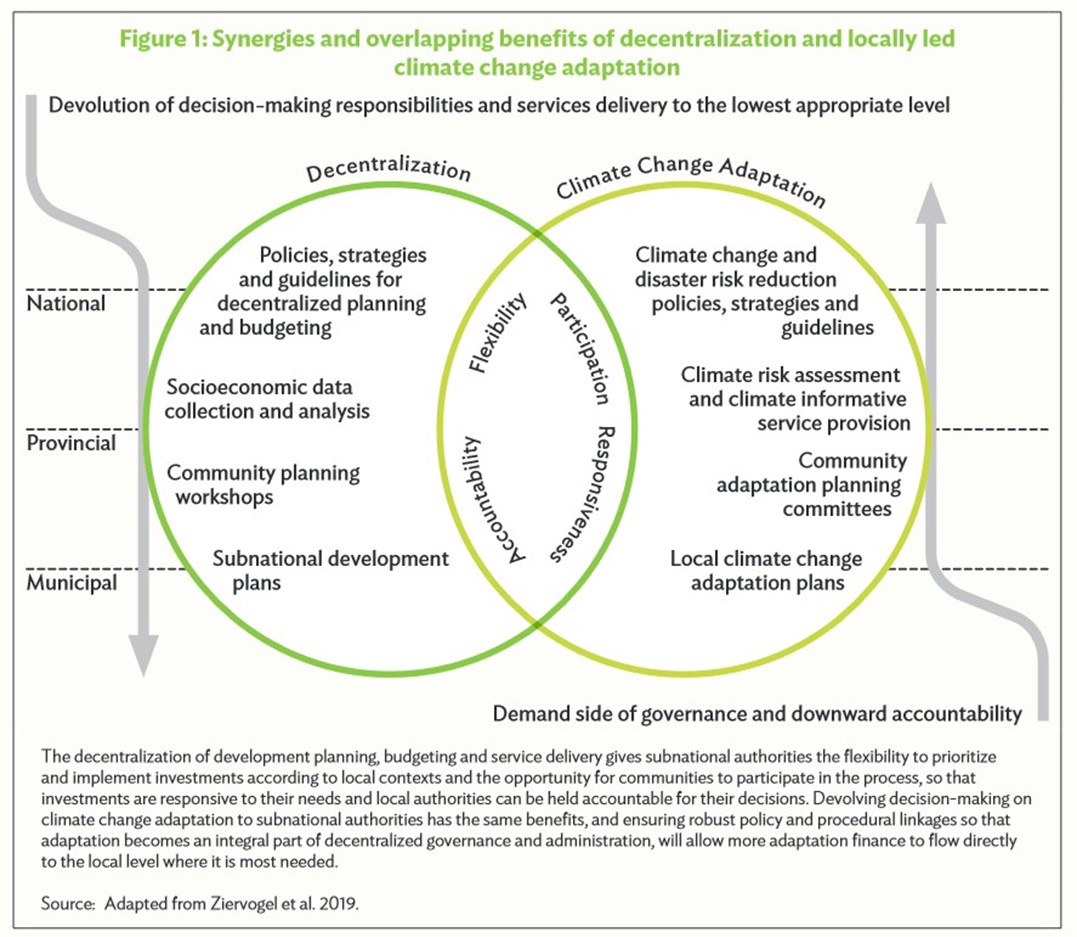

Locally-led adaptation is key. The most effective adaptation measures are those tailored to local needs, informed by community priorities, and implemented at the grassroots level. This localized approach not only responds to the immediacy of climate change impacts, but also ensures adaptation strategies resonate with the community’s lived experiences. However, as with all strategies, certain barriers can impede progress, such as ecological and physical constraints, limitations in knowledge and resources, and social dynamics. Yet, despite these challenges, several standout characteristics define successful adaptation initiatives: a commitment to addressing the foundational causes of vulnerability, a drive toward community-led innovations, a strong inclination toward decentralized governance, a relentless focus on overcoming social barriers, and devolved finance.

(From Asian Development Bank, 2023)

Devolved climate finance is a mechanism designed to redirect climate finance to where it is most impactful: the local level. When local entities have resources and decision-making authority, they are empowered to spearhead climate resilience and adaptation efforts. Countries, such as Kenya, Mali, and Senegal, are testaments to this approach’s efficacy, as they have incorporated decentralized finance mechanisms into their climate strategies. Central to the success of such mechanisms are principles, such as community-led planning, support to established institutions, emphasis on social inclusion, and a steady focus on public goods. Yet, several challenges persist, such as the fragmentation of funds, potential compromises in budget data quality, and issues of capacity and coordination.

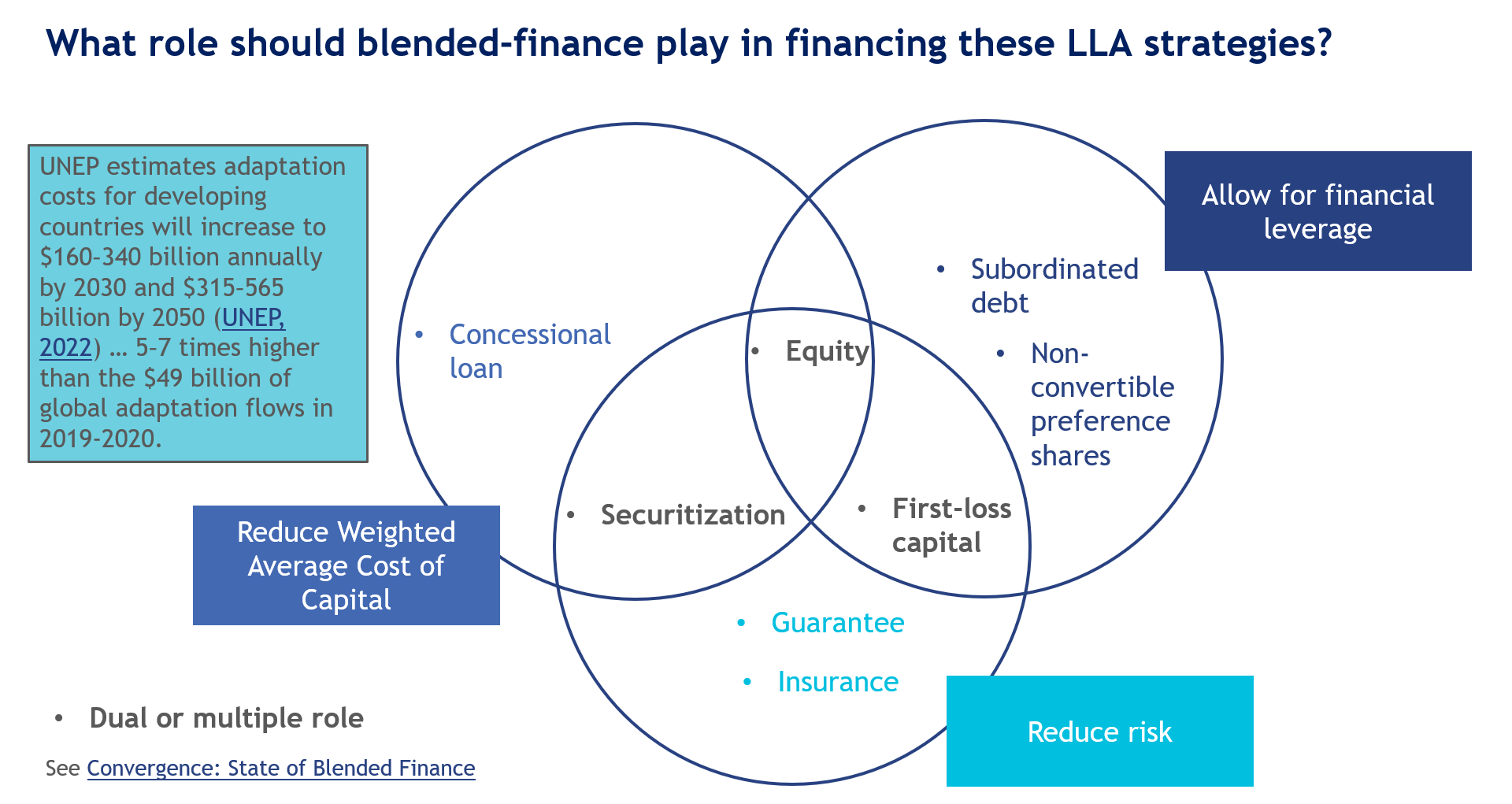

The private sector is an often overlooked but critical player in adaptation financing. If enabled by international, philanthropic, and public sector funds, private finance’s vast potential could usher in a new era of progress towards sustainable development goals and impactful climate adaptation.

Blended finance, which combines public and private sector investments, offers a promising avenue to reduce risk and the weighted cost of capital, and to leverage capital to catalyze innovation and market transformation, at scale.

Over the past 25 years, a range of organizations, including MSC, have been instrumental in integrating local communities into the development, financing, and monitoring of projects. It is imperative to harness these accumulated insights to advance locally-led adaptation planning. A comprehensive approach should prioritize community involvement and incorporate existing regulatory, policy, climate science, and financial dimensions alongside the governance to monitor, evaluate, and learn from the implementation of locally-led adaptation plans.

We need a methodology that harmonizes national policies with local governance and future climate forecasts to provide a robust framework. A pivotal aspect of this strategy involves the diversification of financing mechanisms, which range from international climate funds to community-based organizations, and thus ensures an integrated approach to both planned and autonomous adaptation efforts.

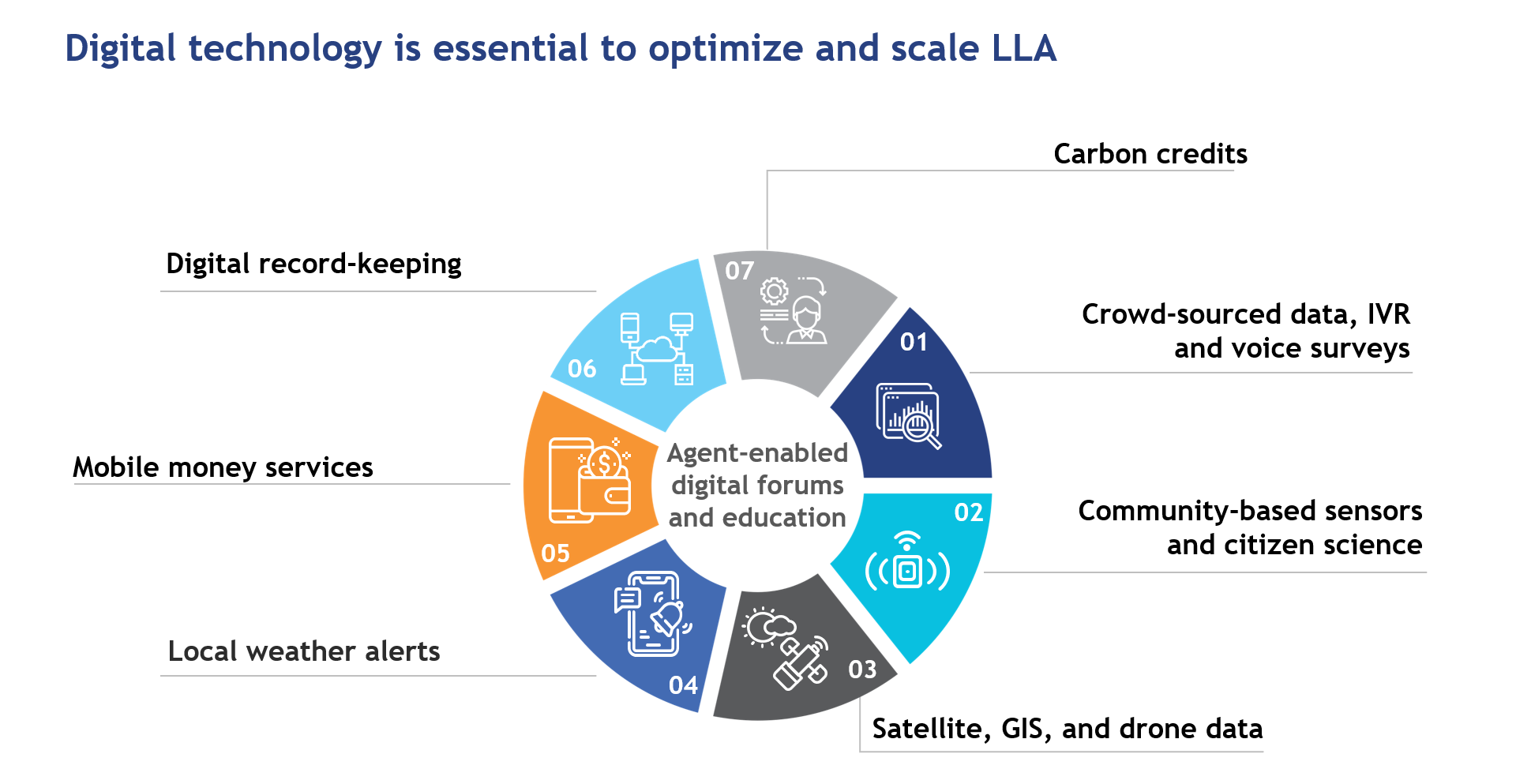

Digital technologies can potentially facilitate, accelerate, and mainstream locally-led adaptation planning and the governance functions of monitoring, evaluation, and learning, to refine and optimize adaptation initiatives. Cash-in cash-out mobile money agents, microfinance institution staff, or agricultural extension agents in climate change-vulnerable areas could become nodal points to help develop LLA plans. They can provide access to key data and insights for the participatory planning process, and then enable the management and governance of the implementation of those plans. Perhaps most importantly, they also often are embedded in the communities most impacted and therefore may have the trust and access to local communities that can subsequently inform appropriate solution design.

This approach to LLA would entail these agents acting as “catalysts of change” who use and facilitate access to a range of digital technologies. These technologies can be deployed to support and scale LLA planning and monitor the implementation of those plans for performance-based payments. AI-enabled online forums in local languages could offer opportunities for communities to share knowledge, discuss challenges, and co-create adaptation strategies. Mobile platforms could be used to deliver educational content on adaptation practices suitable for local conditions, as well as a range of financial services and payments against performance or for carbon offsets.

Community-based and operated weather sensors, satellites, drone services, and feedback platforms could be leveraged to develop community-led plans as well as provide a means to report on progress and challenges in real-time. These technologies can provide insights and recommendations to improve adaptation initiatives alongside local and national climate adaptation policies. Thus digital technologies could help with the development, monitoring, and governance of implementation of adaptation plans and enable smart contracts to reward the achievement of performance goals.

Digital technologies could complement the effectiveness of LLA strategies by providing increased accessibility for rural communities as well as for the MFI staff or CICO and agricultural agents that serve them. However, these digital tools must align with the local context, needs, and language to foster community participation, knowledge sharing, and sustainable adaptation practices.

Particular care must be taken to ensure that the poorest and most vulnerable have the opportunity to participate and/or lead in the planning and monitoring exercises (Jones, 2010).

We look forward to partnering with organizations that are prioritizing locally-led adaptation and identifying ways that digital technologies can support their impact.

For a more detailed discussions of these issues, please see the CIFAR Alliance whitepaper on Locally-led Adaptation.

Written by

Graham Wright

Group Managing Director

Anant Jayant Natu

Associate Partner

Partha Ghosh

Senior Manager

Wendy Chamberlin

Vice President - Research & Advisory at Busara

by

by  Jan 19, 2024

Jan 19, 2024 4 min

4 min

Leave comments