Empowering female smallholder farmers with gender-responsive agri-finance solutions

by Emma Odera, Shalom Mbugua and Albert Bundi

Apr 25, 2024

5 min

This blog addresses the challenges faced by women smallholder farmers in Uganda, such as limited access to finance due to a lack of land titles. It suggests legal reforms, gender-responsive financial products, and increased decision-making roles to empower these women and enhance their economic and agricultural productivity.

Grace is a smallholder farmer in Uganda whose cultivation depends on seasonal rainfall. She relies solely on her half-acre land for income, while unpredictable weather limits her productivity. Grace would be able to transform her agricultural practice if she had access to an agricultural loan. She could then buy an irrigation pump and start cultivation all year round. This would improve her crop production and potentially increase her yield by 50%. However, banks are unwilling to lend to her because she lacks a land title. Countless women like Grace continue to face an uphill battle to access formal finance to transform their agricultural livelihoods.

Agriculture is Uganda’s largest source of employment. It employs 66% of the population. Women like Grace contribute 72% of the agricultural labor force. Yet, female farmers have less access to productive assets, which include financial services. The World Bank estimates that the reduction of gaps in access to assets for female farmers can lead to a 20 to 30% yield increase per household.

Access to agricultural finance and its use are low in Uganda. Only 11% of the population borrows for agriculture. MSC conducted research on smallholder farmers in Uganda to understand the challenges they face when they access credit. The study found that high interest rates and lack of collateral are common issues, especially in areas where land ownership depends on informal customs and traditions. This limitation restricts their access to financial services and full participation in the agricultural value chain. Additionally, the limited presence of financial institutions in certain regions further restricts farmers’ access to financial services.

The seasonal nature of agriculture also poses challenges for farmers as it leads to income irregularities for them. As a result, they struggle to repay loans regularly. Smallholder farmers can earn as much as USD 7,568 in the harvest months and as little as USD 54 in the lean months, which highlights their financial constraints. Some respondents cited challenges with monthly charges on financial accounts, which are difficult to manage due to agriculture’s seasonal income patterns.

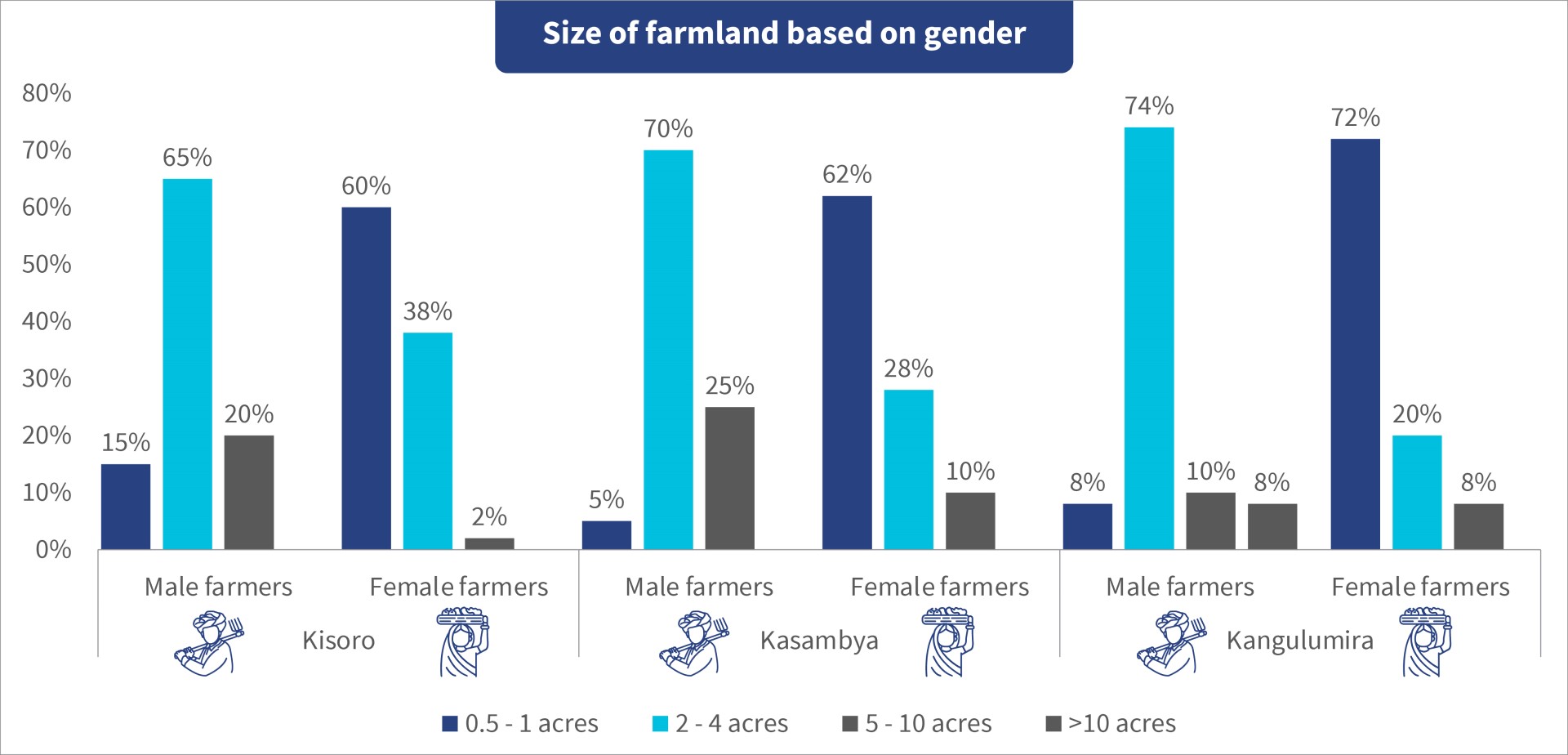

As noted above, land ownership among women is often informal, which leads to limited control over land transactions. Women own smaller plots of land, which range from 0.5 to 1 acre.

Additionally, men are the primary decision-makers in agricultural and household matters, which can limit women’s autonomy in the choice of crops, farming techniques, and access to financial services. Figure 1 shows this disparity. It is an extract of findings from three towns in Uganda based on MSC’s study. It shows that male smallholder farmers manage larger plots of land. In contrast, female farmers mainly engage in farming activities on smaller plots. This gender-based distribution highlights the need for interventions to address these inequalities and empower women in agriculture.

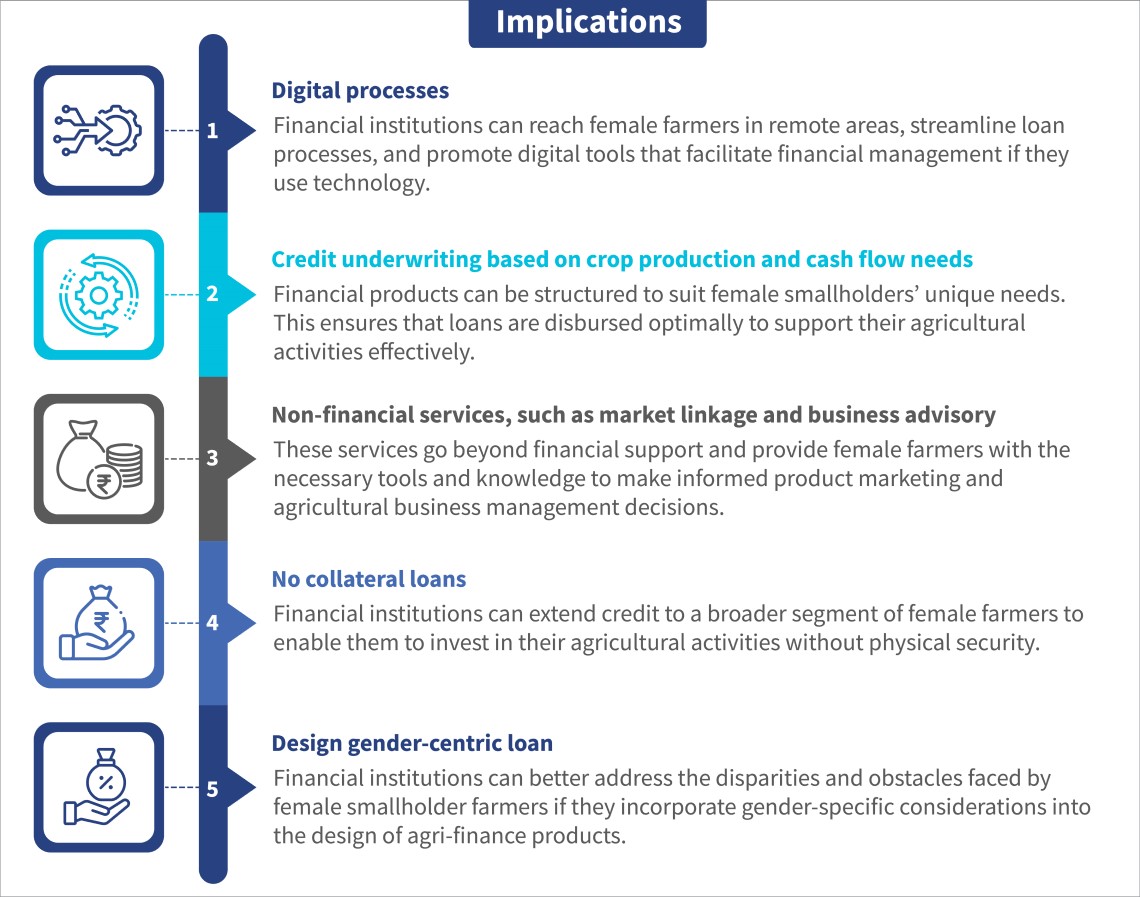

Financial inclusion for female smallholder farmers is not limited to access to credit. It also involves the design of products that address their unique challenges and empower them economically. The figure below shows some key implications in the design of credit products specifically for female smallholder farmers, which MSC identified during our recent study.

Recommendations to change the status quo

Promote gender equality in land ownership: Government agencies and policymakers should implement policies that promote gender equality in land ownership and ensure secure land rights for women. Additionally, support programs should facilitate women’s access to land rental agreements and promote gender-inclusive rental practices. In Rwanda, the land tenure regularization program ensured women’s land rights and increased productivity and income for female farmers.

Grant access to legal titles: Advocate for legal reforms that grant female smallholder farmers secure land ownership rights and access to legal titles. The land titling project was one such initiative that positively impacted Peru. It improved women’s access to land titles and enhanced their economic security and decision-making power.

Increase access to digital channels: Financial institutions and lenders should develop initiatives that provide training and resources to help female farmers overcome digital barriers and use technology for agricultural credit. myAgro, a social enterprise in West Africa, has significantly enhanced its engagement with female farmers, who now represent 65% of its clients. The organization offers a savings program that empowers smallholder farmers to afford essential agricultural inputs, such as seeds and fertilizers, through a prepaid scratch card system.

Enhance women’s participation in decision-making processes: Stakeholders should establish programs that empower women to participate in decision-making processes, provide training on marketing strategies, and promote gender equality in agricultural organizations. The FAO has established Dimitra Clubs in Africa, which are community-driven platforms in several African countries. These countries include Burundi, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Malawi, Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal. These clubs empower rural communities, particularly women, through enhanced participation in community life and decision-making processes. Africa has 600 Dimitra Clubs, and 60% of the members in these clubs are women.

Segment female smallholder farmers: The segmentation of female smallholder farmers into subgroups should be a fundamental step in the design process and the development of such gender-tailored products. This segmentation reveals the nuanced similarities and differences among women and informs product uptake and usage patterns. One Acre Fund focuses on smallholder farmers, many of whom are women. Its programs often tailor support to the unique challenges faced by female farmers. It recognizes that women may have different levels of access to land and resources than men. This tailored support implicitly involves segmentation, which acknowledges and addresses the specific barriers that female farmers face.

Conclusion

The market demand for gender-responsive agri-finance credit signals a growing interest to address gender disparities within the agricultural sector. Moreover, the research planning, implementation, and prototype design processes must consider gender. Qualitative research methodologies, such as human-centered design (HCD) or MSC’s Market Insights for Innovation and Design, enhance the efficient design of impactful solutions and cater to the diverse needs of female smallholder farmers.

Collaboration among banks, FinTechs, MFIs, and development partners is essential to seize opportunities to improve female smallholder farmer’s access to credit. MSC’s support to such institutions has been pivotal in the development of credit products tailored to empower female farmers. Through such tailored solutions, women like Grace would no longer need to depend on the vagaries of unpredictable weather and look forward to a better and more secure future.

by

by  Apr 25, 2024

Apr 25, 2024 5 min

5 min

Leave comments