Empowering communities: The vital role of local government in locally led adaptation (LLA)

by Pranav Singh

Nov 8, 2023

7 min

This blog post emphasizes the importance of capacity building to empower local governments and communities to efficiently allocate and use available resources for locally-led adaptation.

What is locally led adaptation? Why is it important?

The recent attention paid to adaptation and resilience is heartening, especially for communities in developing countries vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. We may even witness a landmark agreement on doubling adaptation finance at COP 28 this year. Adaptation finance is sorely needed, particularly in low-income countries, to make people and their surrounding infrastructure more resilient to the impacts of climate change. Yet, it forms a significantly low proportion (13.3%) of global climate finance compared to mitigation finance. Unlike mitigation, which focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, adaptation warrants a diverse set of context-specific activities. This makes adaptation finance challenging to track and potentially unappetizing to invest in.

Most programs within this relatively shallow pool of adaptation finance follow a top-down approach—and involve the communities they claim to benefit nominally, if at all. Less than 10% of global climate finance reaches communities directly, which deprives those most affected of both finance and agency to drive climate action that best suits their needs. A locally led adaptation (LLA) approach can remedy these twin injustices and ensure the effective and sustainable use of the scarce adaptation funds.

Locally led development is a “process in which local actors—encompassing individuals, communities, networks, organizations, private entities, and governments—set their agendas, develop solutions, and bring the capacity, leadership, and resources to make those solutions a reality.” Despite its limitations, LLA offers a new paradigm that places communities and local actors at the center of decision-making and funding for climate adaptation. It recognizes the value of local and indigenous knowledge and is not limited to consultative and participatory approaches.

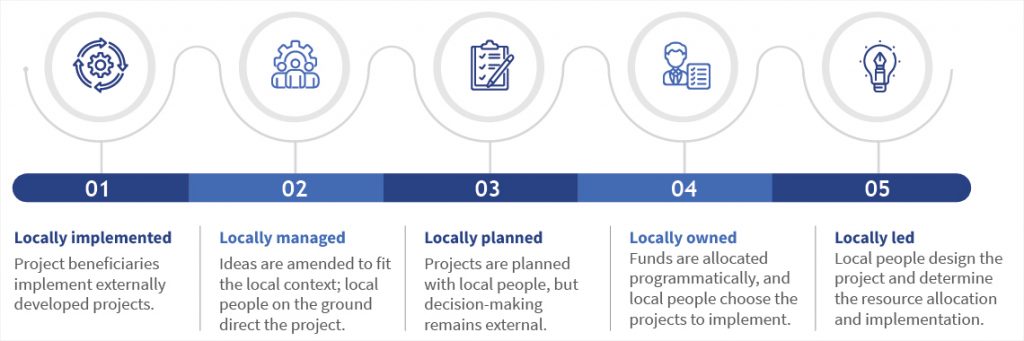

Continuum of local contributions to adaptation programs and projects (adapted from Locally led adaptation: Promise, pitfalls, and possibilities)

A conscious mainstreaming of LLA can ensure that climate action is not impacted by:

- Limited community participation: Top-down interventions may not involve local communities adequately in decision-making, which leads to a lack of ownership and buy-in from local actors and thus jeopardizes sustainability. Further, the program risks maladaptation if it fails to account adequately for local needs and context.

- Insufficient resources: External planners often underestimate the resources and time needed to implement a program and thus undermine the effectiveness and sustainability of local adaptation efforts.

- Inclusivity and equity concerns: Externally driven programs may not adequately identify and prioritize the needs of disadvantaged groups, such as women, youth, and indigenous peoples, who are often the most vulnerable to climate change impacts.

The role of local government in driving locally led adaptation

Local governments are crucial to driving LLA efforts because they are intermediaries between local actors and national authorities. Local governments are close to the communities and understand the local context and needs deeply. These include social, cultural, and economic factors that influence vulnerability and the communities’ adaptive capacity.

Although constrained, local governments also have the mandate and resources to make decisions that affect their communities, including finance, technical expertise, and human resources. This is particularly advantageous. Compared to externally funded programs, locally owned and financed projects are more likely to be effective and sustainable. Our consultations with the Ugandan local government representatives reflect this, as they cited project duration and funding as key drivers of a program’s sustainability.

Key functions of the local governments in driving local climate adaptation plans:

- Climate risk assessment: Undertake activities to determine the magnitude and frequency of climate change’s effects and people’s vulnerabilities and adaptation capacities. A key enabler here is investment in long-term climate forecasting and advisory dissemination.

- Coordination with key stakeholders: Assign a focal point person to coordinate climate change actions with key public and private stakeholders and create collaboration platforms. A participatory approach through robust community engagement would ensure inclusivity and equitable outcomes within the program.

- Land use and urban planning: Develop and enforce climate-proof physical development plans by strengthening the approval process and supervising construction

- Licensing and regulation: Establish a regulatory environment for infrastructure development, provide standards and guidelines, and strengthen enforcement

- Awareness generation: Undertake community sensitization campaigns on climate change’s effects and suitable adaptation and mitigation measures

- Planning and budgeting: Integrate climate change actions in local governments’ plans and budgets

- Monitoring, evaluation, research, and learning: Develop key performance indicators to monitor and report implementation progress. Evaluate program outcomes promptly and objectively and use the lessons to improve program implementation continuously.

- Legislation: Develop suitable ordinances and bylaws to foster community resilience to climate change impacts in the future. Create a conducive policy environment to facilitate innovation within the private sector, such as finance and technology.

- Catalyze funding: Develop and submit financeable proposals for climate change to the suitable ministries and development partners. Seek partnerships with the private sector—both formal and informal sources—to unlock increased adaptation financing.

Source: Adapted from the Climate Change Handbook for Local Governments (Uganda), 2019

Strong relationships and acceptance within the community establish legitimacy and reinforce the local government’s role in driving LLA. Local governments can help express and elevate local concerns so that they are accounted for adequately within national climate policies and programs. This would also ensure indigenous and local knowledge is mainstreamed into national adaptation plans. Moreover, the trust and relationship between local governments and communities can catalyze increased community participation and communication and lead to increased buy-in and ownership of the project.

Key barriers to adaptation planning in local governments

Local governments are crucial to driving local climate action planning and implementation. Yet, significant barriers inhibit their proper functioning in developing countries, where the need is dire. We identified several frequently cited challenges based on MSC’s work in mainstreaming climate and disaster risk planning and resilience building for Uganda’s local governments. Most local government functions identified above require some degree of technical expertise:

- Limited awareness: Local government may lack awareness of the effects of climate change. A lack of strategies at their disposal to address the challenges can often lead to inaction.

- Technical skills: Risk and vulnerability assessment, land use and spatial planning, and risk-informed budgeting are specialized processes that require dedicated upskilling.

- Management skills: Driving a community-led adaptation project can be akin to managing a complex, multi-stakeholder project with diverse values, interests, and preferences. Coordination of such projects needs advanced management skills, including effective communication, mobilization, negotiation, and conflict resolution.

- Analytical skills: Local governments often lack the data for risk-informed planning and budgeting. This is driven by underinvestment in data collection and monitoring systems and limited capacity to use the existing data to drive decisions. Monitoring, evaluation, research, and learning (MERL) functions are essential to managing the complexity, uncertainty, and context-specificity inherent to the LLA approach. Even when the MERL functions are outsourced to specialized private agencies, often from concerns of accuracy and objectivity, they benefit from ownership within an informed and capable local government.

The lack of funding and resources was another frequently cited barrier to the effective pursuit of climate adaptation planning at the local level. This is driven by:

- Institutional barriers, such as inadequate revenue sharing and devolution of power between the local governments and national authorities: The local governments may not receive adequate untied funding that offers them the agility to finance adaptation measures in response to the varying context and needs at the local level. Often, local governments may not be allowed to seek direct funding from external funders.

- Limited awareness and capability to seek external funding: The local governments face significant challenges in pursuing the limited global climate adaptation funds available. A lack of transparency, an assortment of financing channels, and complex rules of funding and reporting have created a complicated ecosystem that few local governments can navigate.

The role of capacity building in empowering local governments and communities

While resolving the institutional barriers would require a concerted effort to overhaul the policy and public financial management systems, capacity building offers a promising entry point. Increasing the local governments’ awareness and capacity can drive the demand for systemic reforms. Simultaneously, it can equip the local government to allocate and utilize the available resources efficiently to drive locally led adaptation. The local governments also serve as conduits of information to communities, which would thus enable the diffusion of knowledge to a broader community beyond the immediate beneficiaries of the capacity-building measures.

Case study: Capacity building as a lever to build resilience at the local level

Uganda’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution and the Third National Development Plan (NDP III) reaffirm Uganda’s commitment to prioritize adaptation as the primary response to climate change, and seeks to increase resilience at the grassroots level. The role of local governments has gained increased importance as the country seeks to strengthen adaptive capacity across all levels, particularly in vulnerable sectors, and address loss and damage.

MSC collaborated with the Ministry of Local Government and the United Nations Development Programme in Uganda to develop a training module to mainstream climate risk management and resilience building within local government plans. The module helps the local governments mitigate and manage the impacts of future risks that emanate from natural and human-made hazards and enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities. It achieves these goals by strengthening local governments’ capacities in climate change adaptation, disaster risk management, natural resources management, spatial and infrastructure planning, and resilience building.

Countries, especially those that bear the full brunt of climate-induced disasters and shocks, will closely watch the COP 28 proceedings to see definitive action on adaptation financing and “loss and damage” fund. Even as the international community is held accountable for climate action, countries must overhaul their sub-national frameworks to facilitate climate adaptation and resilience at the local levels in a context-effective, sustainable, and transparent manner.

Local governments and community-based organizations will be indispensable in this transformation and should be the primary beneficiaries of climate financing. To this end, capacity-building measures serve a dual purpose. Such measures create an informed demand through awareness and sensitization and ensure the necessary upskilling of local stakeholders to effectively use resources and drive locally relevant adaptation and resilience measures.

International donors, therefore, must play their part in empowering local actors and communities by provisioning funds, skills, and technology that do not replace but supplement the rich pool of local indigenous knowledge and expertise. Only by ensuring that local actors have equitable access to power and resources can we address the injustices of climate change and those of mainstream adaptation approaches.

by

by  Nov 8, 2023

Nov 8, 2023 7 min

7 min

Leave comments