District readiness for G2P payments: Ready or not… Well, still mostly ‘not’ part – II

by Ritesh Rautela and Lokesh Singh

Mar 6, 2014

4 min

Here we discuss how MicroSave has responded to system challenge for EBTs and developed “district readiness assessment” (DRA) tool, to assess the readiness of a district to deliver EBTs.

The previous blog in this series highlighted the complexity of setting up a system to deliver electronic benefit transfers (EBT) effectively in India. And how there seemed to be little rationale for the selection of districts for pilot-tests and rollout of Aadhaar-enabled EBTs. We suggested the need for a tool that helps governments to decide which districts to choose for DBT roll out depending on districts’ readiness level? And, that such a tool may also help us all to understand which areas need focus for successful rollout?

In response, MicroSave has developed “district readiness assessment” (DRA) tool, to assess the readiness of a district to deliver EBTs.

The DRA tool was pilot-tested in two districts in East Uttar Pradesh. It was used to assess these districts’ readiness to make payments under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) and ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) schemes. The readiness of stakeholders was assessed on different indicators, and the preliminary key findings are summarised below:

- CICO Coverage: In both the districts, the number of agents actually present is far lower than the number provided in the State Level Bankers Committee(SLBC) or different banks’ websites. Out of a list of 673 agents (as available from secondary sources), only 124 could be found available and ready for transactions (i.e. agents are physically present in their location with front-end technology to allow account opening and transactions). If seen in the context of total villages of over 1,000 population, this comes to minuscule 4%. This is in line with a recent study on the availability of agents in rural areas. Further, it is unclear whether these agents will have enough liquidity to service customers, an aspect that most agents have not thought about and the parent bank/agent network manager has not asked them to prepare for.

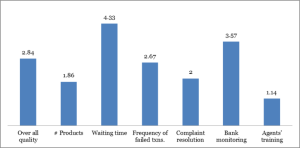

- CICO Quality: CICO quality is measured in terms of service delivery, complaint resolution and capacity building of CICO agents, and it was found far from satisfactory in the two districts that were surveyed. The few agents working in these districts were not well trained, and were ill-equipped to handle customer queries, and resolve issues. The graph below shows scores to highlight the difference between the desirable and actual situation on a 0-5 range, with 5 being actual equals desirable, and 0 being actual completely fails to meet the desired level of service.

- CICO Sustainability: The majority of the CICO agents who were available were not able to earn even 40% of what they expected from the banking business to run CICO outlet viably. This has an adverse effect on their motivation to continue in the long run. This is a matter to concern because a large number of agents have already gone dormant or have quit the business because of low returns. If more agents stop offering the CICO services, beneficiaries will be left with no choice but to go to bank/post office branches and of course trust in the system will decline significantly.

- Department-Bank Readiness: In case of MGNREGS, complete beneficiary data is digitized and each beneficiary is mapped to one account; but many of these accounts are not mapped to only one beneficiary. In many cases, payment to multiple beneficiaries is mapped/ transferred to one single account. This defeats the purpose of EBT, which envisages that an individual’s benefits be paid directly to him/her. For ASHA payment, the situation is worse as data is not digitized and the payments are processed on the basis of manual vouchers.

- Beneficiary Awareness: This is one area that should have preceded DBT roll out, but it seems that no efforts were made by any stakeholder, or that the efforts were ineffective. In both the districts, more than 70% of beneficiaries are not aware of bank-CICO linkage; and over 80% do not know that G2P payments can also be received through such CICO agents. This is, of course, not surprising given that there are so few CICO agents in the two districts.

Preliminary results of the DRA clearly suggest that the districts are not ready for efficient implementation of G2P programme. There are important gaps in individual stakeholder level preparations, and the coordination between the stakeholders is very weak. A better approach to roll out of G2P payments in any location is to assess the readiness of different stakeholders, systems, and infrastructure and then make a decision. If the scores on different parameters are too low, the government should first address the challenges before rollout. DRA report gives ample data and information along with analysis and recommendations that can form the basis of corrective measures.

For successful implementation of EBT, all the stakeholders need to come together and make concerted efforts instead of working in silos; and will need to have data on the readiness of districts to deliver G2P effectively.

Written by

by

by  Mar 6, 2014

Mar 6, 2014 4 min

4 min

Leave comments