Designing adaptive worker protections for the digital economy

by Manoj Nayak, Rhifa Ayudhia and Lenny Nurharyanti Rosalin

Jan 13, 2023

5 min

The rapid digitization of work in the informal economy offers an opportunity to increase women’s participation in the labor force. However, women continue to grapple with a disproportionate burden of unpaid work at home. Thus, any tangible increase in women’s participation in the labor market will call for adequate social protections that reduce this burden. This blog discusses the importance of reimagining the social protection architecture for the digital economy.

This blog is the second of our three-part series on women’s participation in the digital economy. It is an outcome of MSC’s work with the Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection in Indonesia for the G20 Ministerial Conference for Women Empowerment. Read the first blog of this series here.

By mid-2021, a typical informal worker earned only 64% of their pre-COVID-19 pandemic earnings, while 82% of the workers could not replace any savings they exhausted through the pandemic months.

Informal workers constitute 55% of the global workforce who lack access to any social protection program. The absence of social protection disproportionately impacts women as they comprise most of the informal workforce. The world urgently needs better social safety nets that protect workers during a crisis.

The rapid digitization of work in the informal economy offers an opportunity to increase women’s participation in the labor force. However, any tangible increase in women’s labor-market participation will require adequate social protections that reduce the burden of women’s unpaid work at home. This blog discusses the opportunities and challenges in creating such a social protection architecture in the digital economy.

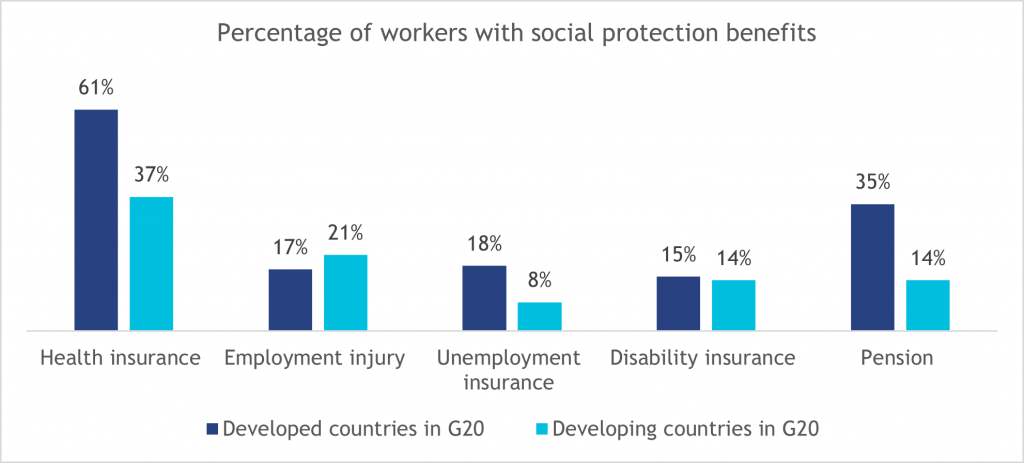

The divergence in access to social protection among developed and developing economies in the G20

Despite the availability of formal and legal work in a digital economy, a wide gap persists in access to social protection in developed and developing countries. The table below summarizes the difference in access to social protection among workers on web-based platforms for developed and developing countries in G20.

Limited regulations on universal social security coupled with fiscal challenges lead to inadequate publicly-funded protection for informal workers in developing economies. Moreover, the low state capacities of developing countries create hurdles in developing and implementing social protection in the digital economy.

Women’s burden of care increased during the COVID-19 pandemic

Women traditionally face more barriers than men in accessing the job market. Our previous blog described the challenges women faced from historical disadvantages, such as low education and skills.

Moreover, women face barriers, such as sociocultural norms that control women’s mobility and economic activities. The COVID-19 pandemic magnified unpaid care and domestic workloads, with women carrying the heaviest burdens across all countries. Women’s time spent in unpaid care work accounted for 16.4 billion hours per day, with women contributing 76.2% of the total time spent. These trends threaten the continued progress of including women in the labor force.

In this context, the growth of “flexible” digital platforms has a dual effect on women’s work. The flexibility allows women to continue in the labor force by adjusting work timings to available time. Yet, their economic interactions continue to depend on the as social roles around domestic and care work take priority. Such expectations force women to work longer hours to earn as much as their male counterparts.

Developing adaptive worker protection measures for the digital economy

International Labour Organization’s World Employment and Social Outlook report in 2021 points to at least 777 active digital platforms focusing on online web-based and location-based platforms in January, 2021. Such digital platforms have grown from 128 to 611 in the G20 countries in the past decade. These platforms provide economic opportunities that benefit workers but also involve substantial risks around the regularity of income, working conditions, and social protection. Workers in the digital economy are typically classified as independent contractors and lack comprehensive coverage under labor or social security laws.

Many governments design social security systems assuming “standard” employment with a traditional employer-employee relationship. As a result, nonstandard not offer social security protection. Informal workers in the digital economy are more exposed to risks due to the nature of their work and the inconsistencies in employment terms. The increasing number of gig workers across economies, coupled with events like COVID-19 that led to further economic disruption, highlights the need for robust worker protections.

Moreover, social protection policies are not gender-responsive. More than 100 countries adopted social protection measures to cope with COVID-19—yet only 22.8% were gender-sensitive. The lack of a traditional employee-employer relationship for workers in the digital economy has further complicated social protection for them. Therefore, employer-linked social protection may not suit workers in the digital economy.

In light of these factors, G20 member countries need to modify existing social protection architectures to suit the needs of the digital economy, and here are some of our recommendations:

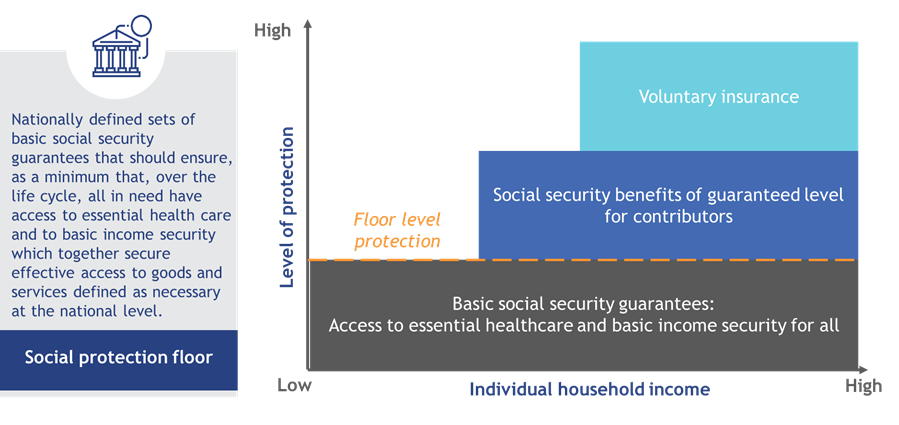

1. Set a national target to ensure a gender-responsive universal social protection floor for workers

Governments must ensure that all workers have a basic safety net irrespective of the nature and type of their work. Governments must set a national target followed by an adequate budget allocation to create a gender-responsive universal social protection floor for workers in line with the ILO Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202).

G20 governments must take steps to create inter-governmental funding to support developing and emerging nations in creating such social protection measures.

2. Social protection architecture should respond to newer digital work or enterprises offering non-standard work

In addition to universal social protection floors, governments must develop accessible and affordable contributory programs for workers, platforms, and governments to participate.

Workers in the digital economy often offer their services across multiple platforms. Designing social protection for such flexible workplaces will require moving away from the current employer-linked social protection systems. Governments can achieve this by encouraging the creation of platforms that allow workers to accumulate their social protection benefits across multiple workplaces. However, arriving at the ideal model for each country should be an iterative process that accounts for the respective labor force’s unique characteristics and the preexisting social security model.

3. Publicly funded, affordable, and quality care infrastructure to increase women’s participation in paid work

Governments must adopt policies that recognize, reduce, and redistribute women’s disproportionate burden of unpaid work in line with SDG 5.4.

Some examples of such initiatives include the Survey of time use and valuation of unpaid domestic work in Mexico, the provision of a range of public care services in Uruguay, and employment-related care policies in South Korea.

Policymakers need to adopt innovative financing programs to help create publicly funded, affordable, and quality care infrastructures within communities to reduce the burden of unpaid care on women and create jobs in the care sector.

The pandemic’s impact on informal workers—especially women—highlights the need for a well-rounded social protection architecture that protects workers. A responsive social protection system is important because the growth of digital platforms in the past decade has changed the nature of the economic interaction of informal workers. Governments must now take the lead in ensuring that workers—especially women—have greater access to protections that increases their ability to keep working.

Read our next blog to learn how an inclusive social protection architecture for the digital economy can drive greater formalization.

by

by  Jan 13, 2023

Jan 13, 2023 5 min

5 min

Leave comments