Coping measures for “measurement” in the time of COVID-19

by Rahul Chatterjee and Monica Dutta

Jun 9, 2020

6 min

COVID-19 has seen governments across the globe walk a tightrope as they scramble to contain the spread of the disease while keeping the economy stable. In this unprecedented situation, ground-level data for evidence-based decision-making assumes critical significance. This blog looks at five key lessons from MSC’s research on COVID-19.

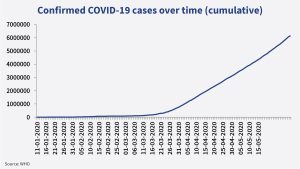

As of 2ndJune, 2020 10:06 am CEST, the COVID-19 pandemic reached 216 countries across the globe, infected 6,140,934people, and claimed 373,548 lives. Despite the unprecedented global effort, the now infamous curve of COVID-19 shows no sign of “flattening”. Governments across the globe continue to struggle as they impose containment measures to reduce the spread, keep the health infrastructure up and running, and manage the fragile economy. In this unprecedented situation, donor agencies and research agencies across the globe are doing their bit by trying to equip policymakers with ground-level data for evidence-based decision-making.

In the past three or four months, we have seen the publication of multiple research reports. These research exercises focused on different aspects of the crisis, namely health behavior, food availability and consumer behavior, economic impact and finances, and government responses, among others. At MSC, we have a deep understanding of the poor, their household-decision making and gender dynamics, and the relationship of these factors with governments, regulators, and private sector players. The pandemic made it imperative for us to spearhead efforts to support policymakers with evidence and generate recommendations for decision-making through a series of synergistic research studies.

Five key lessons

One common challenge in all these studies was our inability to conduct face-to-face interviews to gather evidence. The uncertainty around how long the crisis will continue and how long we would have to wait to return to normal life made the process of planning the research difficult. Our solution was the tried-and-tested telephonic or online surveys. In this blog, we explain five key lessons from the research conducted by MSC in the past two months.

- Collaboration: Given the seriousness of the situation and the need to allocate resources optimally, donor agencies have been collaborating to minimize the duplication of efforts. In India, two major donor agencies have joined hands to create a “COVID-19 Research Network” for researchers to come together to coordinate, share knowledge and innovations, pool resources, and communicate their efforts. These efforts should maximize impact and establish ethical and equitable research practices. Globally, we also see a growing argument in favor of open research and data collaboratives to ensure ease of access to insights from completed research studies, and thus to minimize redundancy.

- Technology: The pandemic has paved the path for increased use of technology for research. We have seen several channels and platforms assume greater significance. These are here to stay even in the post-COVID-19 scenario:

- Telephonic, online, IVR- and SMS- based surveys for data collection;

- Virtual data quality assurance mechanisms, including telephonic spot checks and back checks as well as reviewing audio recordings of interviews;

- Project management through the greater use of platforms like Basecamp (to track projects)and Zoom or Microsoft Team (for training sessions and meetings);

- The rise of webinars and dashboards (based on Tableau or Google Data Studio) for dissemination.

- Innovation: As the dilemma continues between sticking to textbook robust research methods and their feasibility in a time of continuing lockdowns and social distancing, innovations have flourished. We have optimized the length of questionnaires for telephonic interviews, dropped unnecessary questions, and brought about a disciplined focus that was often missing in previous surveys. We have seen an increased use of the snowballing method to source telephone numbers for interviews, increased use of consumer panel databases available with survey agencies, and use of customer databases of implementing agencies and financial service providers.

We have also used implementation staff, such as MFI managers and loan officers, as data collectors to utilize the existing rapport that they have with respondents. We have seen the rising use of mobile phone data to track population movement and location data to identify communities at risk. Another interesting trend is the increased use of high-frequency data collection methods like financial diaries.

- The need for speed: Policymakers need rapid and regular data insights to understand ground realities. Yet there is an important trade-off between rigor and usefulness. Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) might provide academic rigor, but quick policy recommendations substantiated by data are the need of the hour. We just cannot wait for months or even years to see the impact of changes in policy. The rapid identification of successes and loopholes in the implementation process is as important for policymakers as the impact itself.

Thus, agile monitoring and feedback loops are essential, as are the channels to provide insights to key decision-makers. This also highlights the need for country-level research systems that can respond to this type of emergency by providing high-frequency monitoring data to policymakers. For years, MSC has been providing rapid feedback to the Government of India to identify successes and failures in policies and to do course correction as needed.

The successful implementation of DBT in Fertilizer in India is one such example where we provided rapid and iterative feedback to the government for it to modify parts of the program as it was scaled up across the country. Similarly, MSC created an index to rank states to provide rapid feedback on COVID-19 to the Indian government based on the states’ initiatives.

- Process optimization: A fast turnaround time is crucial for gathering evidence during this difficult time to inform policymakers. We have therefore seen a lot of process optimization in researches. We streamlined the processes by:

- Shortening the preparatory phase by cutting down the slack time between the initial preparation, development of the research framework, and its conversion into a tool;

- Reviewing the in parallel by multiple parties and incorporating all possible suggestions in joint calls.

The report structure is prepared ahead of the data collection commences and analysis syntaxes are readied before the data starts coming in, based on the data structure decided in the beginning. This is setting a new benchmark for the industry, and even in the post-COVID scenario, we can expect results within a similarly rapid turnaround time.

Several words of caution

Research agencies are competing with each other to reveal results before anyone else. In the process, they sometimes miss important nuances. We are seeing many “percentage values” that are offset with inadequate discussions of the story and the drivers behind them. A meaningful research story often depends on the collection of qualitative data, which is much harder to do effectively over the phone and requires skilled moderators. Recitation of data, without answering the “why?”, “where?” and “so what?” questions that flow from it, short-changes policymakers.

We have also seen that where pre-enrolled panels of respondents are used, these have often answered too many quantitative and qualitative questions already and suffer response fatigue—an upshot of the plethora of research underway.

Another challenge is the fact that sometimes these insights come at the price of compromising statistical robustness—a challenge that the reports themselves do not acknowledge adequately.

Moreover, there is a high chance of making technology-driven data collection the “new normal” in the post-pandemic scenario. Yet that will widen the already existing exclusion of peoples’ voices from the ground, as we depend evermore on survey agencies that offer access to pre-enrolled panels of respondents, which are typically designed to provide rapid feedback to FMCG companies. Hence, these panels are therefore typically drawn from the affluent and middle classes rather than the poor and vulnerable communities that have been hit the hardest by the pandemic.

Moreover, the entire population, which largely lacks access to the phone or internet, is by definition completely excluded from these insights. These very people are most vulnerable to the pandemic. It is therefore essential to be selective in choosing panels and to force these research companies to focus on gathering voices from the poorer and marginalized corners of society.

Just as we have changed the way we conduct our lives in a fundamentally different way after COVID-19, research protocols, too, are likely to undergo a seismic shift as the world looks toward the long path of recovery.

by

by  Jun 9, 2020

Jun 9, 2020 6 min

6 min

Leave comments